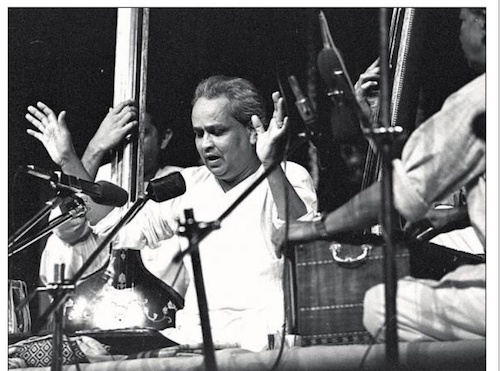

Kumar Gandharva

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

A brief profile

Namita Devidayal, April 6, 2023: The Times of India

From: Namita Devidayal, April 6, 2023: The Times of India

Sometime in the 1980s, Kumar Gandharva was invited to perform at an auditorium in Dadar, Mumbai. When he reached the venue, the organisers rudely told him to move ahead as they had to clear the way for a politician, the chief guest. His friend, who had driven him there, protested that this was the artiste himself, but they were not bothered. Without a word, and with no assistance, Kumar Gandharva picked up one tanpura, his friend picked up the other, and they climbed up two steep flights of stairs to the auditorium on the second floor. Once he was on stage, Kumar Gandharva delivered a wonderful performance. His music soared like the swan he often sang of, ‘Ud Jayega Hans Akela’, wrapping the audience in an ethereal cocoon. When asked later if he was upset by the organisers’ behaviour, he said, “yes, of course, but the 500 who have gathered here should not suffer on that account. ” Kumar Gandharva may have passed on, but his voice continues to soar, unbuffered, giving solace and pleasure to many. It is the voice that defies boundaries and breaks hierarchies to reach the space where everyone dissolves into that roar of silence. What did he mean when he sang of shunyata or emptiness? Was his music classical or folk? Why did he become the voice of the mystic poet Kabir? Who was this man? Shivaputra Siddharamaiah Komkali was born to a family of singers near a Shiva temple in a village called Sulabhavi in Belgaum, Karnataka 100 years ago. As a child, he revealed an extraordinary gift: he could memorise and mimic any kind of music. With this talent, the child star was given the name Kumar Gandharva by the swamiji of the neighbouring ‘math’, and was sent at about age 10 to learn music from BR Deodhar, who had started a music school in Mumbai’s Opera House. The name ‘Kumar’ stuck, he was never known by any other.

The year India got Independence, Kumar Gandharva got married and gave what for a long time would become his last recording on All India Radio. He had been diagnosed with tuberculosis and forbidden to sing. But for a man steeped in faith, even what seems like a dagger transformed into a magic wand. He moved to a town called Dewas in Madhya Pradesh, known for its clean, dry air and its ambient folk music. In Dewas, the songs of the villagers and the wandering devotional or sufi singers became a constant background hum in his life. The music now played in his interior world. He braided lighter folk elements into ragas, miraculously never compromising on the integrity of either. He befriended the mystic Kabir’s nirgun poetry that was soaked in the vision of oneness about the ultimate formless reality, and peppered with lilting reminders that the great potter returns all to the same mud.

“People who knew Kumarji tell stories of how he loved vegetables and flowers, birds, books and rain – how attentive he was to things and moments,” writes Linda Hess in her book ‘Singing Emptiness’. “He enjoyed gardening and shopping; carried multiple shoulder-bags to the market so the fresh vegetables would not get crushed; engaged friends in long conversations about the beauties of bhindi; set a tape recorder in the garden early in the morning to catch the conversation between two birds. ”

When he was given permission to sing again, six years after he had been diagnosed, he was a shooting star singing a kind of music that had never before been heard. His music transcends history, geography. It even transcends music, for it hits the purest vibration that connects all. (Kumar Gandharva’s birth centenary will feature a series of performances through the year across different cities. )