Left/ communist politics in India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents[hide] |

1951-2019

Performance in Lok Sabha elections

May 25, 2019: The Times of India

From: May 25, 2019: The Times of India

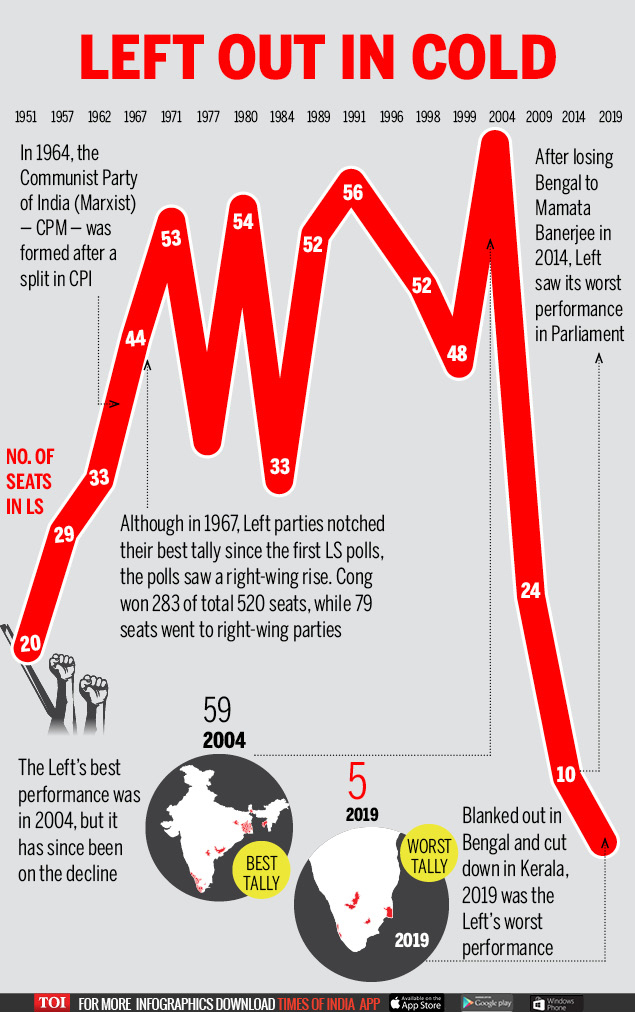

With just 5 seats, Left goes further downhill

NEW DELHI: The Left’s electoral journey began as the Communist Party of India (CPI), Revolutionary Socialist Party (RSP) and Forward Bloc. In the first three general elections, Left was Congress’ main rival and principal opposition in Parliament. But after it turned in its best performance in the 2004 polls, picking up 59 seats, it got caught in an abject slide that saw its tally slide to 10 in 2014. But it was further downhill from there, with the Left notching its lowest ever Lok Sabha tally in 2019.

2019

Left politics without the Left

May 24, 2019: The Times of India

In Kerala, the Left has been left with one lonely seat in Allapuzha. Worse, the Left Front has lost everything in its former strongholds in West Bengal and Tripura. They have won one seat, and are leading in three seats in Tamil Nadu This is the lowest-ever point for the communists, and it may not be easy to reverse the situation, given BJP’s embrace of its cadre and Trinamool’s takeover of its social constituencies in WB, which they dominated for 34 consecutive years until 2011.

How far they’ve come — the undivided Communist Party of India was the largest opposition party in India’s first Lok Sabha election. It drew strength across India from Punjab to Telangana and Andhra Pradesh, from Tamil Nadu to Bihar. The Left parties had their best parliamentary performance in 2004, with 64 seats. They supported UPA and held it to a common minimum programme, until they fell out over the US nuclear deal in 2008.

But either way, the free-fall in the left’s fortunes is proof that it no longer speaks to most of the electorate. BJP, Congress and every other party pitches itself to the poor, and seem to do it more persuasively. In Bengal, it had betrayed itself with Singur and Nandigram — siding with industry, attacking its own supporters. Their critics claimed that they tilted too far towards minorities.

Perhaps, this loss of power could be the very thing that energises their movement. They can focus on the struggle, rather than the compromises of running a state.The left, after all, has a big role to play in a dispensation they are at odds with, especially given the BJP’s 180-degree opposite view. It could look beyond internationalism and class, and also draw in anti-caste and environmental movements, battles over gender and sexuality.

Of course this won’t be easy. The first term of the Modi government targeted the parts of civil society that take up such causes, the supportive associations of those who resist it. In its second term, this tendency will intensify, and it will be Left mobilisations that take the hit. Violence between R S S and Left workers may increase.

But around the world, the rise of right-wing populism has been met by an upsurge in left energy, in democratic socialism. Young people who resist the right are more drawn to the clarities of the left than the compromises of centrist politicians. The hitch, of course, is that it may not be CPM, CPI and others like them who rally for this change. We might just end up having a left politics without the Left parties.