Libraries: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Bengal

As in 2023

Neha Banka, Aug 12, 2023: The Indian Express

Piles of moth-eaten, decades-old books lay abandoned along the corridors and staircases of the 251-year-old Rammohun Library and Free Reading Room in central Kolkata.

But the scenario is not very different in most libraries across West Bengal; in some cases, it is much worse. For instance, the 116-year-old Amta Public Library in the state’s Howrah district that has been closed since March 2021, has over the years, become infested with cockroaches and rats, its main entrance blocked with vines and creepers and its century-old collection of books in a state of ruin, librarians told indianexpress.com.

At the ‘Festival of Libraries’ held on August 5-6, organised by the Ministry of Culture, Professor Ajay Pratap Singh, the director-general of the Kolkata-based Raja Rammohun Roy Library Foundation, said the Ministry was planning on introducing a Bill in Parliament to bring libraries under the Concurrent List, which includes the power to be considered by both the central and state government. This would mean that the central government would also have control over the operation of libraries. At present, libraries are controlled by state governments.

In India, Maharashtra has 12,191 government-funded public libraries—the highest in the country, followed by Kerala with 8,415, Karnataka with 6,978 and West Bengal with 5,251, according to data by the Raja Rammohun Roy Library Foundation. While the Kerala Higher Education Minister has expressed displeasure over the proposed move, other state governments have not issued any statement yet.

“In Bengal, we have 2,484 government-aided libraries. 13 are government libraries. There are seven special libraries and we have 2,000 private libraries,” says Biswabaran Guha, the treasurer of the 98-year-old Bengal Library Association. There are also several libraries at the sub-divisional, block, municipal and gram panchayat level. “So we have over 4,000 libraries here,” says Guha. West Bengal’s association with books and libraries is likely the result of a few historical and socio-cultural factors.

The early years

During the 19th century in undivided Bengal, access to western education and the development of print culture occurred simultaneously. The emergence of a greater number of books resulted in the slow establishment of libraries in the region, where the first of these institutions was the Calcutta Public Library in 1836.

By the end of the 19th century, there were over a hundred public libraries across the region, mostly developed using funds and donations provided by philanthropists and others who had received formal education. While some provided monetary assistance, others would offer parcels of land, contributing to the establishment of libraries in whichever way they could. Some 1,800 libraries in West Bengal were established through the contributions of the public in pre-Independence India.

“The growth of libraries across the subcontinent coincided with the freedom struggle and these libraries and gyms became places where freedom fighters would gather to plot against the British,” says Guha.

The beginning of the 20th century marked changes to the way libraries operated in the subcontinent. Political leaders in the subcontinent believed there was a need to coordinate the activities of these libraries and to organise movements that would help inculcate reading habits and generate more awareness on the need for education. In 1924, the first All India Public Library Conference was held at Belgaum in Karnataka, under the presidency of Chittaranjan Das.

The conference adopted a resolution for the formation of library associations in each province of India. Subsequently, a meeting was held in Calcutta’s Albert Hall in December 1925, presided by J A Chapman, the then librarian of Kolkata’s Imperial Library, now called the National Library. It was at this meeting that the All Bengal Library Association was formed with Rabindranath Tagore as its president.

Kolkata’s neighbourhood libraries

Many of the city’s oldest libraries continue to operate, albeit in a poor condition, where indications of their historical significance can be found in their collections of rare books and plaques indicating the building’s age. Today, several of these libraries are accessible only for designated hours during the day, but continue to get loyal visitors who prefer these rooms for the space they provide to read and learn in silence. Many of them are located inside the paras of north Kolkata and have almost become neighbourhood libraries.

“The para libraries started during British India. One goal was for them to operate as centres for revolutionaries and freedom fighters,” says Dr. Joydeep Chanda, the librarian of Gurudas College in Kolkata. The second was for keeping banned literature like Nil Darpan, the play written by Dinabandhu Mitra in 1858–1859 that portrayed the plight of indigo farmers, and copies of Bande Mataram, an English-language weekly newspaper founded in 1905 by Bipin Chandra Pal and edited by Sri Aurobindo during the freedom struggle. “It wasn’t easy to find these publications during that time. But members of the Anushilan Samiti and other similar revolutionary organisations were all members of these parar libraries and they would donate these books to these libraries,” says Chanda.

Libraries are an integral part of Bengali culture, say librarians and library regulars interviewed for this report.

“In Bengal, in our para, when we had someone who was deeply interested in education, we would collect books and develop small libraries for these students. Otherwise where would parar boys and girls study? So these neighbourhood libraries would be persevered for them, as well as for the women of the para, so that they would have a place to access books. This is how parar libraries developed. This started changing when television entered households, and then the internet, but it’s not true that people have stopped visiting these libraries,” says Chanda.

Located in the Entally neighbourhood, the 141-year-old Taltala Public Library, established in 1882, is located deep inside a bylane in central Kolkata. Only accessible on foot or a two-wheeler precariously navigating the narrow para, the public library was closed on the day indianexpress.com visited. It is among the oldest public libraries in the city and has a rich repository of books in English and Bengali. It is also a surviving example of the important role that parar libraries played in public education, pre and post-Independence.

“Today, 90 per cent of the libraries in West Bengal are in bad shape,” says Guha. With the exception of the Rammohun Library and Free Reading Room, five of the city’s oldest libraries were closed when indianexpress.com visited.

Librarians at some of the state’s oldest libraries and individuals knowledgeable about the library movement in Bengal say that the library movement has considerably weakened over the past 12 years and approximately 50 per cent of the libraries in the state are fully or partly closed.

Lack of library recruitment

“After 2010, there was not even one recruitment for any library-related post in the state. As a result, out of the 2460 libraries, 1,200 libraries are presently fully or partly closed. Of the 1,200, 800 are fully closed now and 400 are considered partly closed, which means they open once or twice a week,” says Chanda. The remaining 1,260 of these libraries are open, but they aren’t necessarily in a good condition, say librarians interviewed for this report.

The cycle of existing library staff retiring and an ongoing pause in hiring since 2010, has resulted in a shortage of trained library staff, resulting in forced closures of these public institutions across the state.

“Approximately 85 per cent of designated posts for the jobs of librarians and support staff are empty in public libraries across the state. There are provisions for 5,520 posts, of which 4,500 are vacant. There are just 920 full staff managing public libraries across West Bengal,” says Chanda.

In 2021, the West Bengal state government announced that it would recruit approximately 700 library staff across the state, but examinations for recruitment are yet to be held. At the time of publishing this report, indianexpress.com was yet to receive a response despite multiple requests, from the state’s Minister for Mass Education and Library Services, Siddiqullah Choudhury.

Presently, several universities in the state and the Bengal Library Association offer training for library services. The Association, for instance, has 130 seats open every year for potential candidates seeking training for future employment in libraries. “Almost a 100 of these candidates are from rural Bengal and the seats are almost full,” says Chanda.

A space for learning

For students, these local libraries, including those at the village level, provide access to books and resources — particularly for higher education and job prospects — that they would otherwise be unable to afford.

Founded in 1883, the Bagbazar Reading Library located on K C Bose Road in north Kolkata is among the oldest functioning libraries in the country. This 140-year-old library has over 90,000 books and journals and is also known for Rabindranath Tagore’s frequent visits to this institution during his student years.

Rajat Das took over as librarian of this institution four years ago. He also works as a librarian at two other historic libraries in the city — the Bani Institute and the North Entally Kamala Library. A persisting paucity of sufficient library staff in West Bengal has resulted in librarians like Das, having to manage more than one library in a week, just to ensure that the doors of these institutions are open, even if only for a few hours every week, for readers who need them.

“These are such old libraries and they need staff. But we are not able to operate them well or keep them open regularly due to a lack of library staff. Funds are also a problem. A few volunteers from the neighbourhood assist me. They are parar lok (people from the neighbourhood). They look after the library and do it without money. They do this out of love for the library. It is not possible to do this job alone,” says Das.

On two days a week that he is able to open the library, some 25 people turn up on an average. “Many come to borrow books. Students will come from far off places to do research here. The neighbourhood’s people lose out on a chance to access the library and so many research scholars have to go back when they find it closed,” he says.

Located adjacent to the Minerva Theatre in north Kolkata, the founding members of the 134-year-old Chaitanya Library were Gaur Hari Sen, Kunj Behari Datta and Rabindranath Tagore. The library served as an important location for discussions, debates and lectures during the subcontinent’s freedom struggle. One of the most significant public discourses delivered at the Chaitanya Library included Tagore’s lecture on the life of Bankim Chandra Chatterjee.

It is a misconception that people are not interested in reading or libraries any more, says Chanda. “What do you mean when you say that people don’t go to libraries? If something is open once or twice a week, nobody will go there”. The 98-year-old Entally Bani Institute in the Hazra Bagan neighbourhood of Kolkata began through the donations in the form of books, operating out a residential house till it moved to its present location in 48 Pottery Road which was only meant to be a temporary location, till the library eventually ended up permanently operating from this address. Most of its rooms are closed when the librarian is away managing other libraries, and the few that remain open have been converted for other uses, for example temporary medical camps.

The only day of the week that Junik Sengupta is not present in a library is Sunday. Pursuing his Masters in Physics from Gurudas College, Sengupta was previously a member of the Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture library. After his father’s death, he found himself unable to afford library fees, resulting in his inability to access the library near his home. “My professors helped me secure special permission to access the Rajabazar Science College library and the S. N. Bose National Centre for Basic Sciences library. They are close to my college and have an astonishing collection of books because they are so old,” says Sengupta. The internet does not hold answers to all of students’ questions or even provide all the resources that they need. Not all texts and documents are available in their entirety online, and subscriptions cost money. For research scholars and students like Sengupta, libraries remain the only spaces where they can access expensive, rare documents and other academic assistance that they find unavailable and inaccessible online.

In 2016, the Gurudas College library decided to open their doors by 9 am because the librarians realised that even a delay by an hour was causing some students to lose out on valuable study time. “Many students are the first in their families to study in college. Some don’t have electricity at home. Some have too many siblings and it is not a conducive environment to study. So where do they go? They come here to study. When we were opening the library by 10 am, the students started saying that it was causing difficulties in study. Even if there are two to three students, they still come and that is why it is important to keep libraries open,” says Chanda.

Running a library is challenging in these circumstances, West Bengal’s librarians told indianexpress.com. “But we will continue to do this for as long as we can,” says Das.

Heritage Libraries

2023

Sneha Bhura, August 6, 2023: The Times of India

From: Sneha Bhura, August 6, 2023: The Times of India

From: Sneha Bhura, August 6, 2023: The Times of India

From: Sneha Bhura, August 6, 2023: The Times of India

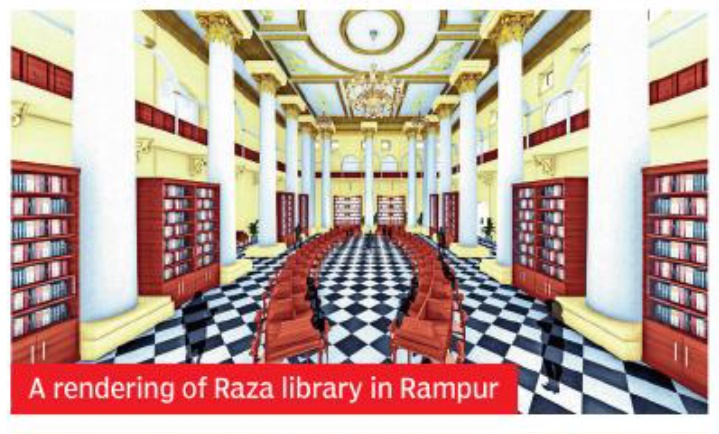

In 1774, Rampur’s first nawab Faizulla Khan, who was of a literary bent of mind, decided to house his collection of rare valuable books, manuscripts, and specimens of Islamic calligraphy in the toshakhana (treasure house) of his palace. Once Rampur acceded to the Union of India in 1949, the collection found a permanent home at the opulent Hamid Manzil within the fort-palace complex of the former princely state.

As the Rampur Raza Library prepares for its 250th anniversary celebrations next year, conservation architect Shikha Jain hopes to build a seamless bridge to its origin story as part of a major dome-to-basement restoration project which began in March this year. “The proposal as per the master plan is to join the toshakhana with Hamid Manzil via an open green space. The approach road can lead to either the former treasure chamber or the library, and in between, we hope to build a cafe where people can sit and read,” says Jain, who as, founder-director of the Dronah Foundation, has led more than 60 conservation and museum planning projects.

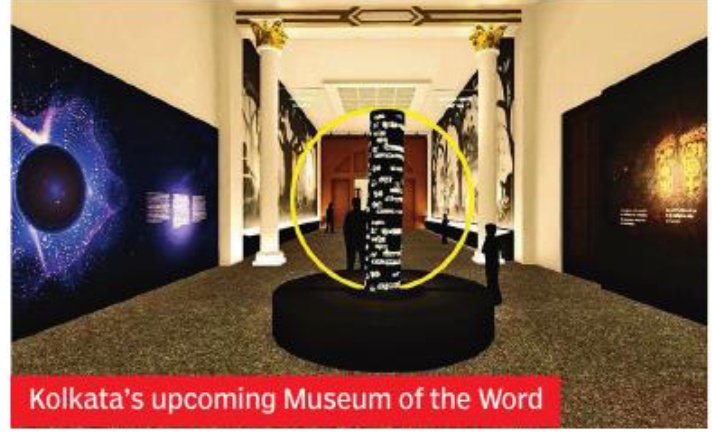

The Raza Library is just one of India’s many iconic libraries getting a facelift. Some are new museums in heritage buildings such as the upcoming Museum of the Word (Shabdlok) at Kolkata’s Belvedere House, another project that Jain is helming. This museum will trace the evolution of India’s 22 official languages.

Mugdha Sinha, joint secretary in the Union ministry of culture, says there is a new awareness about upgrading historical libraries in India. “We have several historic libraries in India which haven’t been listed or mapped. We badly need a national database on such libraries,” says Jain. But work on other projects is on. The National Mission on Libraries in India, an initiative of the ministry of culture set up in 2013, has taken up several major upgradation and digitisation projects which are now in the process of completion. “It is very important that we are able to upgrade the infrastructure of our libraries, such as microfilming and digitisation of manuscripts, as well as services like Wi-Fi, toilets, cafeterias, etc for researchers,” says Sinha.

In June, Mumbai’s historic David Sassoon Library, established in 1870, reopened to the public after a 16-month restoration initiative helmed by conservation architect Abha Narain Lambah. A multi-party project which included donors like JSW Foundation, ICICI Foundation, Consulate General of Israel, among others, the refurbished structure is a rigorously researched homage to its 19th century Jewish-Indian heritage alongside its Victorian and Art Deco ensembles, complete with antique switches, flooring, lamps and original sloping roofs. India’s largest library by volume and public record is the National Library at the 30-acre Belvedere Estate in Kolkata. The estate originally belonged to Mir Jafar, the puppet nawab of Bengal province in the 18th century, who gifted it to Warren Hastings, the first governor-general of Bengal. Built in the Italian renaissance style, Belvedere House housed the National Library until it was shifted to the newly built Bhasha Bhavan within the same premises in 2004. Urban legends will tell you how the 250-year-old mansion is haunted by Hastings’ ghost. “These are just stories. I have stayed up till 3am at Belvedere House overlooking all the repair work and never encountered a ghost,” laughs Ajay Pratap Singh, director-general at National Library. The launch of the Museum of the Word is slated to happen in the next two months, and Singh assures that it will be “world-class”, sans spirits, of course. The mini-auditorium in the old-annexe building is being spruced up to promote authors and book launches on a no-profit, noloss basis. The left side of Bhasha Bhavan will house a reading cafe while the main reading and lending rooms in the library will embrace the ethos of “community drawing rooms” with comfortable seating. Singh says there is also a new state-of-the-art library coming up at Esplanade 5, a property owned by the National Library which once stocked all its newspaper records. This city-hub library at Esplanade 5 will buy and source books and periodicals. “They say the Library of Congress in Washington DC is the greatest library in the world. We want to make our National Library better than that,” says Singh.

For conservation architects, the challenge is modernising a heritage building while ensuring the original character is not lost. “One should be able to make design interventions in such a way that all mod cons are there,” says Dikshu Kukreja, architect, urban designer and managing principal at CP Kukreja Architects, who has designed many institutional libraries across the country, including the central library at Jawaharlal Nehru University and several IITs like Roorkee and Jodhpur. This year, he has been commissioned to revive the colonial Delhi Public Library built in 1951. Currently in the mapping stage to study the structural stability of the edifice, Kukreja hopes to complete the revival of DPL by early next year.

“Incorporating modern-day requirements of function, comfort, technology while accommodating many more students than the library was originally designed for was a daunting challenge for us too,” says noted architect and urban conservationist Brinda Somaya about the Vikram Sarabhai Library project at IIMA. It went on to win a Unesco award for the way in which it retained the original character of architect Louis Kahn’s modernist vision of geometric circles and arches.

For lack of funds, the Madras Literary Society (MLS), an archival lending library over two centuries old which boasts of Aristotle’s ‘Opera Omnia’ from 1619, has chosen a different approach to restoration. Not only can members pay for restoring a book, they can adopt a piece of furniture. “We have repaired and, restored some 17 pieces of old furniture with this program,” says Thirupurasundari Sevvel, secretary and heritage consultant at MLS.

School libraries

2023- 2024

Manash Gohain, January 8, 2025: The Times of India

From: Manash Gohain, January 8, 2025: The Times of India

New Delhi: Govt schools have outperformed private counterparts in library access, with 92% of govt schools having libraries compared to 82% of private schools. The last decade has witnessed substantial improvements in school infrastructure, with over 63,000 schools adding library facilities and 4.4 lakh schools getting electrified, marking growth rates of 6.8% and 32%, respectively.

89% of schools now have libraries on campus, up from 68.7% in 2013-14, according to Unified District Information System for Education Plus (UDISE+) 2023-24 report. Over two crore books were added in the past academic year, bringing total count to 113.3crore, with the average number of books per school increasing from 763 to 770 during this period.

There are multiple states and UTs — Chandigarh, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and Delhi — where all govt schools have libraries. In other big states, in terms of number of govt-run schools, like UP and WB , the availability of library and books are as high as 98% and 94%. However, Bihar, which is one of the five states with over 75,000 state-govt run schools, has libraries on just 59% of campuses. “There has been a marked improvement in infrastructure. Education being a concurrent subject, we keep sending feedback on parameters where states can take note and prepare policies accordingly,” said a senior education ministry official.

Digital library facilities are available in 7.5% of schools. They are present in 6.1% of govt schools. Southern states lead in this domain, with TN at 99.9% and Kerala at 20.7%. Other states such as Odisha also show promising growth at 12.2%. In addition, Kendriya Vidyalayas (KVs) in four states and Jawahar Navodaya Vidyalayas (JNVs) in eight states have over 50% digital library facilities.

Marked improvement in electrification of schools at 92%, with 90% having functional electricity, seems to have helped in improving the digital infrastructure of schools a s well. While 43% of schools still don’t have computer facilities and 46% lag internet connections, growth of computer facilities from 24.1% to 57% in the last decade and parallel increase in availability of internet connections from 7.3% in 2013-14 to 53.9% in 2023-24 is seen as complimentary. As per UDISE+ report, now 51% schools have functional computer facilities for pedagogical purposes.