Linguistic Survey Of India,1927: Ch. I- Introductory

This article has been extracted from |

NOTE: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a book. Invariably, some words get garbled during Optical Recognition. Besides, paragraphs get rearranged or omitted and/ or footnotes get inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. As an unfunded, volunteer effort we cannot do better than this.

While complete volumes of the LSI are available on at least 3 websites, Indpaedia wants readers to access the original chapters in the form in which they were listed by Mr Grierson, and with a minimum number of clicks and effort.

Readers who spot errors in this article and want to aid our efforts might like to copy the somewhat garbled text of this series of articles on an MS Word (or other word processing) file, correct the mistakes and send the corrected file to our Facebook page [Indpaedia.com]

Secondly, kindly ignore all references to page numbers, because they refer to the physical, printed book.

Introductory

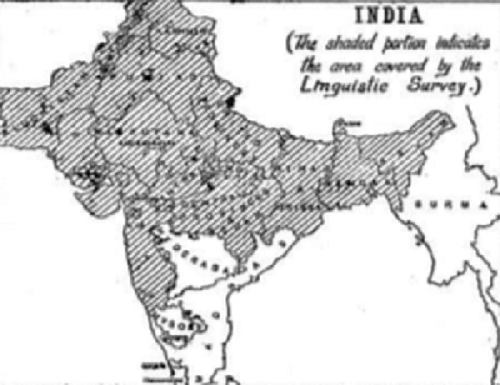

As already stated, this Linguistic Survey does not cover the whole of India. The Provinces of Madras and Burma and the States of Hyderabad and Mysore were excluded from the sphere of its operations. The annexed map shows at a glance the areas included and excluded. The Survey gives estimates of the number of people speaking each language and dialect. It is to be regretted that these figures are ultimately based on the Survey b_ on Census of Cenaulof 1891, butno other course was .practicable. It will, however, be found thn.t., allowing for the necessary ad• justments and for the gro\\,th of population in the intervening thirty years, the totals for the various languages agree remarkably with those given in the Census of 1921.

The reason for the adoption of the Census of 1891 as the basis of the -Survey is that the latter began its operations in 1894. Generally speaking, except when special reasons suggest a contrary course, the linguistic tables of an Indian Census deal with langu!\o"'C8 only. TJley aro not concerned with dialects. On the other hand, for the purposes o.E a Linguistic Survey, an exhaustive conspectus of all the dialects of each language examined forms a n~ary part of its operations.

As explained in the preceding chapter; the first thing done in this Survey was to obtain lists of dialecla from each of the local areas with which it was concerned. They were f~rnished by the • officers in charge of these areas ill 1896 and the following years. Bach local official had at hand the language totals of his District or State according to the Census of 1891. With the aid of his local knowledge, and as the result of local inquiries~ he was able 'to state what dialects of each language were spoken in his charge, and how many speakers there were of each.

The total for the dialects of each language had, of course, to agree with the then existing figures for . the language under which they were grou~. and the figures for the dialects were in this way indirectly based upon the Census .of 1891. It took nearly three years to correct and. arrange the figures so obtained, and it would be a work of too great labour to do it all over again -Oll the basis of a l~ter Census. ,:>nly in the case of a few languages, princi~ll~ those of the• North•West Frontier, was it possible, .for special reasons, to utihzQ the fi,..,"'llI'6&of the la.ter CensUS of 1911.

rbe figures of :the Census of 1921 deal with It. population of 316 millions.

Sunrey figu.ree deal only with 290 millions. The difference is ma.inly due to the

large &.reaB ex~luded. from.. the Survey, but the growth of

the population is al80 to be ta.ken into account. In 1891

that popula.tion was 287 1 millions as aga-inst tbe 816 millioll& of 1921.

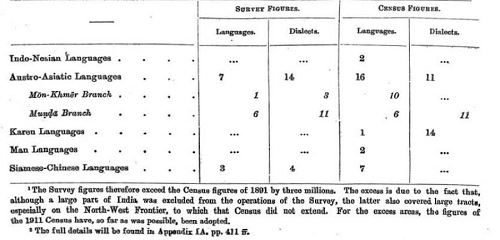

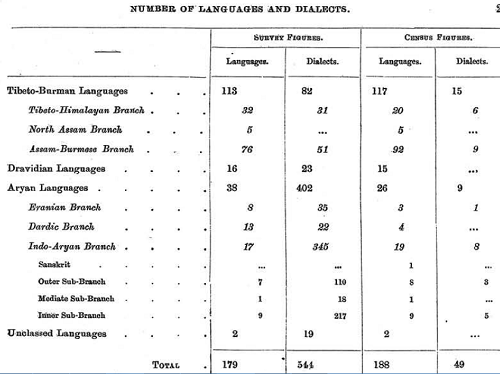

If we take the figures of the Snrvey as they stand, we find that 872 dilferent for eooh &o:re eomf6red. with those of the Census of 1921. But in this enumemtion there ie-110 good dea.l of double oounting, as each i&llgua.ge &nd es.ch dialect is there given a separate number. A better idea of th~ results will be gained from the cOll8idemtion that the Census of 1921 records 190, a.nd the Survey recorda 179 languages, l\8 distinct from dialects.

When counting dialects, it must be borne in mind that, in order to make the total for the dialects tally with the number of the spookers of the language of which they form the members, it baa boon nooessa.ry to count the standard form of the la.ngua.ge as one of the dialects. 'J.'here tlre &190, inevitably ~ ca.ses in which &. language has been returned, but its dialects not mentioned.. For instance, the Khiai Ia.nguage (No.8 in the list) and its dialects are amr.ngedas follows :Kbasi. Standard, Lyug-ngam, Sgl7,teng, TVal', UmpecifierJ.

Here. if we count KbA.sl in the list of languages, we must omit 'Sta.ndard' aud 'Unspecified' in counting our list of dialects and IanguBogUl, or we shall be recording the 8IWDe form of speech twice, or perha.ps three times, ove~. Hence, in the above exa.mple, we ca.n count only three dialects as a.d.ditiona.l to the sta.ndard KImsL language. On this principle, the Ul21 Census bas recorded 49 p.ia.Iects in addition to the general Ia.ngua.ge-ll&l1les. 'J.'he Survey:

Oll the other band, has recorded DO lees than 54.4 du.lect-na.mes in addition to the standard and unspecified forms of the 179 languages. The various forms of speech noted are t herefore 237 (188+4.9) in the Census, and 723 (179+54.4.) in the Survey. Each of these 723 is described in the Survey, in most ca.sea with more or leas complete gramma.tica.l accounts. A summa.ry of the details" of these figures is 8.8 follows :-

It 'Will be noticed that the Sub-Family that contains the greatest numbel' of

monoayllabic. basis. and are hence peculiarly liable to change. lloreover. so far as the area covered by the Survey is concerned, the speakers of the languages of this Subl'amily all live in mountainous dist.riota. As a rule each tribe is separated "from its neighbouN. and langua.ges thus quickly split up into dialects, and each dialect easily ilevelo_JlS into a distinct langua.:,a-e. In this way, wJtile the numl?ar of la.nguages is g reat. the number of speakers of each, averaging about 17,000, is small.

On the other hand, while there are only 1'1 Inno-Aryan languages. the number of

habitat have combined to produce no less than 345 dialects in addition to the 17 standard languages, In this respect, the contrast between the Tibet.o-Burman and the Aryan languages is marked. The monosylill.bic Tibeto-BUI'w1I.1\ speech easily divides and' subdivides into numerous distinct and mutually unintelligible languages, If, as an example of similarly circumstanced Aryan forms. we take the Eranian language3 spoken in and near India. and the D.udic langua.",.:.es, we find that the two branches. like the 11hetoBumtan.

lang-uages •. &re spoken in inhospita.blemotlntain .tracts, but that they -Ilersist, If "the:y dO 'sub-diVide. tbG division is not into m:tttually'tlIiintelligible mnguageS. 'but into mulatally intelligible dia.lects. held together bya common .gramma.t.iC8-1 bam. g';beir synthetic cha.rMt.er preserves each as a constant whole. and even in their rugged h&bitat& they are only 21 in number spread over a. tract extending from Kashmir to the Per8iau frontier Imd from the Pi.mi.rs to the Ambian Sea.. In northern India. where there a.re fewer h~ly tract. to isolate the spoo.kers. the Indo-Arya.n 1s.ngul\,ooe8 8or6 still less in number; and~ though the dialects are many, the relationship of eacb to one or other of thegreatpaorentla.

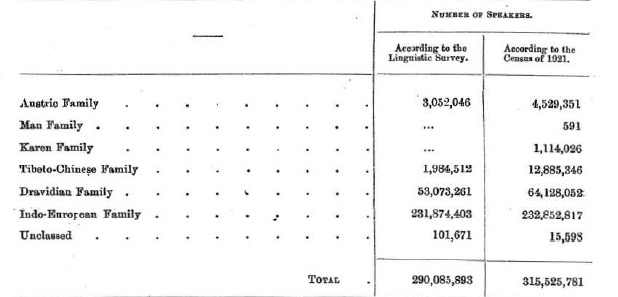

ngus.geaisappa.rentootbemostcarroaJ.observer. I~ has been already stated. that tho Survey dca.l8 with the languages spoken by about 290 millions of people. The following is a. summa.ry of the number of speakers for each linguistic family ;-

As prevIously expll.uned, t.he d.i.lference between the two totall> II> mamly due to the iaot ~t the area. covered by the Survey was not the same as that covered by the Census. A more detailed summary will be found in Appendix IB (pp. 418 ff.), and the complete figure9 for each language are given in Appendix I (pp. 380 ft.).' Roughly apeaking, the total number of speakers whose Ianguagea were surveyed corresponded to throo•quartel'8 of the entire population of Europe. Of these. the speakers of the Austric languages were about equal to the population of Denma.rk. those of the 1'ibeto-Durmu.n la.nguages to half thatof Switzerla.nd. those of the Dravidian languages tomoretha.n the combined populations of the United Kingdom and canada., while the speakers of the Indo-European languages about equalled the combined populations of the Unitt>d Kin¢om. Norway. Sweden. Denmark, Germany. Austria., Fmnce, Spain, I taly and Gn.-ece.

Nowhere are there presented stronger warnings against basing ethnological theories

On linguistic facts than in india.There are many instances of tribes which have in historic times abandoned one languages of tribes which have in historic times abandoned one language and taken to another .A striking example in afforded by the tribe of nahals in the Central provinces.these people appear to have originally on mundi languages.

When I have done so, it has only been to bring f01"ward t heories regarding t he origin of

na.tionalities which have been previously suggested by professed ethnologists. and to

attempt. to throw light on them when they are confirmed. by philology. In oue case only

is it sometimes penni.8sible to draw inferences Il8 to race from the facts presented by

language. When we find a. small tribe clinging to a dying language, lIul"l'ounded by a

dominant language which has IIUpcl"8eded the neighbouring forms of speech, and which is

superseding its ~ngue too, we are generally entitled to assume that the dying language is

theorigwal tribal one,a.nd that it gives a clue to the lat.ter's racial affinities. Take 80S

IUl example the Malto spoken by the hillmen of Rajmahal. This la nguage is decadent.

IUld is surrounded by others which are superseding it. Even if we did not kno'Y it on other grounds, we should. be justified in asserting that ita speakers are Dravidis.n. because their tongue falls within that family. But even t his relaxation of the geneml rule, which was first suggested to me by Sir Herbert Risley. must. as the C8...'16 of the Nahils shows, be exercised with caution. The Nahals are probably Mug.4i by race, but t heir present speech is a.lmost Dra.vidian. Their decadent language is a twofold palimpsest. It first began to be 8uperseded by Dmvidian. and now it is being super'lleded by Aryan. A careless application of Sir Herbert's theory would compel us at the present day to &88ume that the t ribe was of mixed Muq.cJi and Dravidian origin.

With a dominant language we can make no suoh relaxation. I n India. the Indo-Aryan la.ngu~.-the tongues of civilization and of the caste system with all the power and superiority which that system conCers upon those who live under ita sway,-are continually superseding what may. for shortness, be called t he aboriginal languages 8uch as those belonging to the Dravidian, the MUJ;ltJ8., and the Tibeto-Burman families. We cannot liSy that a Tibeto-Bul'ID&n KOch or a Dravidian G6~4 is a.n Indo-Aryan, because he speaks, ~ be often does. an Indo-A1')'I:'D language. The language of the BrihiHs of Baluchistan is Dravidian, but many of the tribe speak the Eranian Balachi in their own homes, and, 0 11 t heoi;hersideoflndis.,90meofthetribe ofKha.rwspea.ka Muq.cJa. other'IJ a Dravidian In.nguage. and others, again. the IndO-Aryan Benga.li. It may be added that nowhere do we see the reverse process of a non-Aryan language superseding an Aryan.

It is even rare for one Arya.n-speaking nationality to abandon its language in favour of another Aryan tongue. We eontinll8.11y find tract.s of country on the borderland between two languages. whioh are inhabited by both communities. living side by side a.nd each speaking ita own language. ~n some localities. such &8 the District of Malda in Bengal. the Survey actually found. .v:illa.ges in which three languages were spoken, a.nd in which the various tribes bad evolved. a kind of lingua fm:nca.to facilitate interoommunica.tion, while ea.oh a.dhered. ~ its own tongue f01" convel"8&tion amongst its Cellows. The, only exception to this generaJ. rule about the non-interc.h&llgeability of Indo-Aryl!-D lrulg9&gfi!! 'BeoiV~1.1v. pp.9.186.

iscatised.1tyreligion. :Islim'has carried_Urdu far tI>lld Wide. and even in Bengal and 0ris8a Wb ftua Musa.1.man Il8Itive6 of t he 'country 'WhoSe veI'IULOWar ill 'IlOt that of their ctStb'pa.triots but is &ll a.ttempt (often a. bad. "one) to reproduce the idiom of "Delhi IIolld Lticknow"

This bringS US to the question of triba.l dialects, a. Subject that has not hitherto received the attention "Which it deserves" The matter is complicated by the faCt that very frequently a tribe gives il;& name'to a. language. not because it is specially tlie Ia.ngu.age of the tribe, but becauSe the tribe is an important one in the area. in which it is spoken. Take, for example, the langiiage'Which in the Ceruius of 1891 was caUed "'Jatki,'j.e. 'the language of 'the (Tat\; tribe.' "But Jatkl is nOt by any meaus "the language of the Jatt tribe alone" It is the language of the whole Western Pa.njab, in parts of which, it is true, Jatta }lreponderate. The name latki is hence misleading (the more so, because the J'at1s of the "Eastern Panjab do not speak ';Ja\;ld') and has been abandaned in the Survey for the more teriatile"' Wa!i;ern Pa6.jibi • or ' Lahuda '. So again, in the hills "north and east of Murrei:l there ate 8. "number of dialeCts varying IlCcordingto locality. One of the important tribes !living in these hills is the 'Chibh. and -these Chibhs every-where speak the di&lect of the ' iillferent places "where they "live. But t he question-begging "name of"'Chibhili' or ' "il:te l&ngtiage of the Chibhs' was invented. and employed to "mean ' the dialect of the l1i1ls nort-h IlIld east of Murree,' wherea.s, there are several dialects spOken by "Chibh"s, ana .. mo'ieo v~r, 'th~ ' Chibhs are by "nO means the only 'peo}lle "Who s"peakthem"

Another group of tribal tongues are those which are cIassed in "the Survey 88 Gipsy 'languages. They are the speeChes "of wandering ciani! "who em-ploy. iuainly fOr lIrof6118iotial 'pUrp0fJ8s, dialects dilfarent froi.tt -tlmt'ijf 'the tract over which they lll&y possibl)" have w8.ndereil lor generations. Th~ "t riMI tongues may be"tea.l1anguages;or •tliey"ttl&y be "argOts in which loeal words 8;fe diStoff.ei:l. iOto a slang like 'What "we ftud in "the 'Le.tiil' patter oC "London thieves 'li'inally,'thore is-Motli.ar clae8 of tribal dia.16I:!ts in which "wa filid •the tongue of a

btit 'oort\lpt:eU and mixed With tha.t of tire "people amongst wliom its "new lot is cast. It is evideIit that if part cif a Ra.iputan& tribe migrates to a "oountry of which Bundeli "is the V61'naCtlla".r, While a;nCither wends its way to a district in which "lfarithi is s"poken. the resu:H.ant 'hmguagcs spoken by the two groups of the lI8tll\e tribe 'Will be "vcry dift'erent, a"itboug.h-bOth art: ba-sed on'Rija:sthAni .. Such ha:s i1C~uaUy occurred in severaJ. insi;&nC611 in the ' Central Provinces, Md there are also in otli.er parts of India. I'nany cMes of imtriigmnt tribes "which have 'preserved their original languages in -more "or (ass corrupted foI'tD"8. 'Pethaps the most striking: example is a colony of speakers of corrupt Sindhi, 'Who liVe iu "the upper Oangetic Doah.

The identi6.c&tionoftlie'bound&riesofa 1.&ngua.ge. or even of a. langUage itself, is nbt'8.hl'l\p'lUl ~ee:sy "matk"r. 'Asal"ule~ unlesil theya"rc 86[i&rated 'by great "etlmic ililter' elioes, or "by some 'niU;ural obstacle, such as a'l'lmge of inountains or a. "large ' river~t India.n la;nguages gradually merge into each other and a.re not sepatated by bard twd fast boundary lines. When such boundaries a.re spoken of, or Me shown on a ma.p. they must 901wa.ys

conventiQnal line there is a. bprder trnct of grea.oor or lessexteut, the l&ngua.ge of wl).ic_h ma.l be cla.ased at will w\th one or other. Here we oft.&:) find that two different obseI;. vers reJ..lOrt dilferent oonmtions as eristing in one 80Ild the SMlle area, a.qd ~th mal be right. J:'or ip.stan~, in 1911, the t hen ~ ~la.oe4. the north~western frontier of Benga.li. fJOme twenty' or thirty miles. to tbe east of tha.t fixed by the Lm~isti() S).lrve~ and I no more m.a.inta.in. that the Survey' figures a.re rig.ht thun that the Cen"sus.figures are wrong. ~m one point of view both are right, and' from another both a.re wrong.

It is a. mere q~tion of personal eeJ,wr.tion. When ther:e is luch a. debatable g.rQ.und. between two la.ngua.geB, I find from experienoo that as a rule a spea.k~ of" oue of ~ la.ngu.u.geB classes the 8~h of' the deba.table ground as belonging to the other. He ll$tumlly seizes on the ~ints strange to him, and, neglectM forms with whiQh he isfa. milia.r. ll'or instance, noo.r BhatnGr t here is spoken a • mixture. o~ Pafijabi &J;ld R8.j!'-3~ thini. The Paiijibh say that it is Rijasthani, but the RaJputM say tJUI.t iJ; is Pailjibi. Another example. tu~ up in the preparation of t he Survey itself. Wbile. I was working at Eastern Hindi Dr. (now Professor) Sten Konow was simultaneously, working atMo.ri~bi . Eoob working independently, we finally met at the junction point where t be curious mixed. dialect oa.Iled. Hal-hi is spoken: From the point of view of Eastern Hindi. I considered that it W808 a form of Marithl. On the other hand, Dr. Konow, looking a.t it t hrough Marithl speotacles, lII.&intained. that it Wll8 & fonn of Eastern Hindi. As the l&st word remained. with me, the dialect appeared in the Mati~hi volume of the Survey, but if it bad been put into the volume for Eastern Hindi, I could not ha.ve said that it was wrongly pla.ced.. .

In the following account of the result.s of t be Survey, I sha.ll, for the sake Areato:whlchUla (ollowfD&: of completeness, refer a.l80 brie6.y to Iangua.ges of India. tbat -...arb appl7. have not ~len within its scope. These a.re mainly the languages of Burma. and of the Doocs.n. Of the fonner, a sepa.rate Survey is now in progress, and it is far from my purpose to a.ttempt to indicate its results. But the languages of Burma. are intimately linked. with those of Tibet and North•Ea.stern India.. w:ul it •would be manifestly improper to leave them altogether out of consideration. The sJilCE'Clws of the Decca.n areDravidia.n.and,limilarly, they bave•congeners in northern India, a.nd denur.nd more than a passing reference. I shall deal fi.rst with the languages of the Austric family, as they a.re proba.bly the earliest forms of spoech that have survived. to the present day. Then I shall deal with those that came probably later into the conntry- the Dravidian and the Indo-Chinese and finally

with the tongues or Aryan origin ,concerning the entry of which into India we can speak with some certainty.