Madhya Pradesh: Wildlife

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Animal Relocation

Rahul Noronha , Man-Made relocation “India Today” 8/5/2017

It is 42 degrees Celsius in the shade. This is the Bundelkhand region of Madhya Pradesh, and wildlife expert Kartikeya Singh, at the behest of the local MLA, is gearing up for a trip to Chhatarpur. His mission: to select a site for the possible capture and relocation of the Nilgai. These animals, native to the area, are known to ravage the crops of local farmers-crops that are especially dear to the poverty-stricken communities of this region.

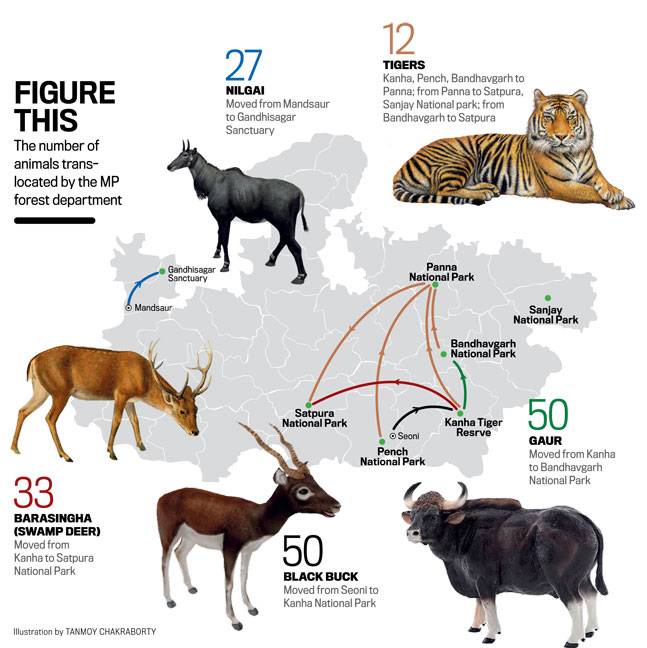

Since December, Singh-who runs Wildlife and Forestry Services, possibly India's only private wildlife management consultancy-has helped the MP forest department capture and relocate 27 Nilgai from the farmed fields of Mandsaur district. The animals have been released into a nearby sanctuary, under the department's alternative plan to deal with the human-animal conflict. It is a more humane option than the traditional method: to reduce the Nilgai population by killing a certain percentage of the animals, a practice known as culling. Many states, such as Bihar, currently employ the latter method. Such relocation of Nilgai from farmed fields to protected forests is just one of many translocation operations undertaken by the MP forest department in the last few years. This approach to wildlife management-though common in countries like Africa-is novel, even out-of-the-box in this country. MP is the only state in the country to have attempted it on such a large scale, marking a shift from 'passive' wildlife management to a more 'active' mode. So far, hundreds of animals have been moved to new habitats.

Initial attempts at wildlife translocation in MP met with failure. The state's first major attempt-to transport several Barasingha from Kanha to the Bandhavgarh national park, in 1982-turned out to be a disaster. Many of the deer died. Discouraged by the failure, the state temporarily abandoned this model of wildlife management.

Almost 27 years passed before the next attempt. In December 2008, an opportunity presented itself when Panna National Park was found to be bereft of tigers. In March the following year, the MP forest department decided to repopulate Panna with tigers, by relocating a few big cats here from other habitats, such as Kanha, Pench and Bandhavgarh. Today, the Panna National Park is home to more than 35 tigers-from the six tigers that were brought here. This was followed by the translocation of 50 Gaur (Indian Bison) from Kanha to Bandhavgarh in 2010 and 2011, with help from South African experts. Before this, the last Bison sighted in Bandhavgarh had been in 1998. Today, the reserve has a stable population. Since then, the MP forest department has shifted Barasingha from Kanha to the Satpura Tiger Reserve, Black Buck from agricultural fields to Kanha and Spotted Deer from Bandhavgarh, Pench and Van Vihar National Parks to various other forests in the state.

So what led the mandarins of the forest department to make another attempt? "Earlier, wildlife management was oversimplified. It is a science that we never acknowledged," says a former chief wildlife warden of MP, H.S. Pabla. In many respects, Pabla is the man who set the ball rolling. It was during his tenure, from 2010-12, that most of the existing translocation operations began. He says one reason for the long delay between attempts was a lack of technical capabilities. "The South Africans helped us a lot in the initial years. They have experience in translocating large animals, which they taught our veterinarians and wildlife staff. They also taught us techniques involving passive capture," he says. "The MP forest department is today in a position to support any state forest department in shifting animals," says Jitendra Agarwal, the current chief wildlife warden of the state. "We have informally offered our services to the Wildlife Institute of India and the National Tiger Conservation Authority."

Pabla's first translocation attempt was to have been moving tigers to the Madhav National Park in Shivpuri. "Then, the Panna National Park crisis blew up and we moved our focus [there]," he says. "There were no more tigers in Panna, the Bison had vanished from Bandhavgarh and many other species were under threat of going extinct in certain habitats. I felt it was time we moved from passive management to active management."

While relocated tigers are shifted individually-after being tranquilised-Bison, Barasingha and Spotted Deer are translocated using the 'passive capture' method. The method involves the setting up of a boma (enclosure) into which the animals are allowed to wander. The exit of the boma leads into the back of a specially designed truck. After the captured animals are herded into the truck, they are transported to their new home, where they are released.

Last month, a batch of Barasinghas was shifted from Kanha to the Satpura National Park, where they were found until the late 19th century. They are currently being reared in an enclosure, pending release. Until this shift, Kanha was the only habitat in the world to have the Hard-ground Barasingha (Cervus duvauceli branderi). "The existence of a single population source, as Kanha is for the Barasingha, is a cause for concern. What if an epidemic strikes? The entire population is at risk of being wiped out. Translocation addresses this threat as well," says Pabla.

In December 2016, the MP forest department carried out a helicopter-and-horse driven Nilgai translocation in Mandsaur. "We erected a kilometre-long funnel that ended in a capture boma. We used 30 horsemen to drive Nilgai into the boma, from an area where there were a lot of complaints regarding damage to crops. On the third day, we also used a helicopter to herd the Nilgai. The animals have been released into an adjoining sanctuary," says Singh.

While the attempt was successful, is the method cost-effective? The department spent Rs 41.6 lakh in capturing 27 Nilgai, or approximately Rs 1.5 lakh per animal. There are an estimated 30,000 Nilgai in MP, half of which are in the vicinity of agricultural fields. "The operation was expensive, but it will not always be so. Many one-time expenditures were incurred," says Singh.

The state expects that the continued presence of wildlife in reserves will help increase the number of visitors. The Panna National Park, for instance, which had lost its entire tiger population by 2008, has benefitted greatly in terms of tourism since the translocation exercise was carried out. "Once tigers were [reintroduced into the park], the receipts from tourist inflows increased from Rs 20 lakh to Rs 1.25 crore. Tourism is big in Panna, thanks only to the bringing back of tigers," says a former field director of Panna National Park, R. Srinivas Murthy. Tourist numbers are expected to go up in Satpura and Bandhavgarh too, where the Barasingha and Bison have been reintroduced. "When tourist itineraries are drawn up in Europe, a lot of thinking goes into which animals can be seen in a given area," says Aly Rashid of Reni Pani Jungle Lodge at the Satpura Tiger Reserve.

The translocation story continues in Madhya Pradesh, and will do so for some time yet. However, the most high-profile translocation projects-such as those involving the Asiatic Lion and the Cheetah-are caught up in administrative and legal tangles. Will the big cats also be given new homes?