Madras Presidency Population, 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Population

Table I at the end of this article (p. 350) gives the principal results of the Census of 1901. The population in British territory at the last four enumerations has been: (1871) 31,220,973, (1881) 30,827,218, (1891)35,630,440, and (1901)38,209,436. The decline of 1-5 per cent, in 1881 was due to the famine of 1876-8, but in the succeeding decade a rebound occurred after this visitation and the rate of increase (15-7 per cent.) was abnormal. The largest and most populous District, Vizagapatam, has an area of 17,200 square miles and 2,900,000 inhabitants.

Excluding the exceptional cases of Madras City and the Nilgiris, the average area of a District is 7,036 square miles, or rather less than that of Wales, and the average number of inhabitants is 1,879,000, or considerably more than that of the Principality. The density of population in the rural areas is twice as great as that of Scotland and equal to that of Germany. It is highest in the natural division of the West Coast (368 persons per square mile), and lowest in the Agencies (69). Excluding the little State of Cochin, Tanjore District (605) is the most thickly- populated area. In rich Malabar there are 100 more people to every square mile than there were thirty years ago, but in the infer- tile Deccan the population has remained practically stationary. During the decade ending 1901, the inhabitants of Kistna increased faster (16 per cent.) than those of any other District, while in Tanjore, which is already crowded and whence considerable emigration takes place, the advance was less than i per cent.

The people of the Presidency are mainly agricultural, and live in villages which have an average of 600 inhabitants each. Except on the West Coast, where most of the houses stand in their own fenced gardens, these are usually compact collections of buildings. In the Deccan they still retain traces of the fortifications which were neces- sary in the troublous days preceding British occupation. About II per cent, of the people live in towns. Only three cities in the Presidency — Madras, Madura, and Trichinopoly— contain over 100,000 inhabitants, and only eight others over 50,000. There seems, how- ever, to be clear evidence that, owing to a variety of reasons, a marked movement of the people into towns is gradually taking place.

Between District and District the migration is usually infinitesimal. Madras City attracts labour from the adjoining areas, and the rapidly developing deltas of the Godavari and Kistna are being peopled to some extent by immigrants from the neighbouring country ; but of the population as a whole about 96 per cent, were born in the Dis- trict in which they were found on the night of the 1901 Census, and another 3 per cent, were born in the Districts immediately adjoining them. Emigration to other countries is, however, rapidly increasing ; and in 1901 Burma contained 190,000 persons who had been born in Madras, Mysore State contained 237,000, and Ceylon 430,000. Large numbers also go to the Straits Settlements and Natal. Many of these emigrants eventually return with their savings to their native villages, and this movement therefore does less than might be expected to relieve the pressure of the population on the soil.

The ages returned (especially by women) have always been exceed- ingly inaccurate, as birthdays are not marked in India in the same way as in England, and few persons trouble to remember, even approxi- mately, how old they are. A very large proportion return their ages as being one of the multiples of five — 20, 25, 30, 35, and so on. Exact deductions from the figures are thus seldom possible. The figures of the 1901 Census still show traces of the great famine of 1876-8, twenty-five years previous, the number of persons between the ages of twenty and twenty-five being much smaller in the Dis- tricts which suffered severely from that visitation than in those which escaped it.

The registration of births and deaths is by law compulsory in all municipalities and in a few of the larger villages to which Act III (Madras) of 1899 has been extended. Elsewhere no penalty is enforceable for omission to register these occurrences ; and though much attention is given to the matter by the Revenue department, it cannot be claimed that the returns are yet complete or reliable, and a high death-rate in a District may be due less to its unhealthiness than to accuracy of registration. In the Agencies of Ganjam and Vizagapatam, in certain zamlndari areas in the former District and in Madura, and in the Laccadive Islands registration of vital statistics has not yet been attempted. In the municipalities the municipal staff is held responsible that the law is obeyed. In rural areas the village accountants are required to keep the returns ; their work is checked by the staff of the Revenue and Sanitary departments, and the results are compiled and criticized by the District Medical and Sanitary officers and by the Sanitary Commissioner.

Though the returns are not accurate, the causes of error in any given area are fairly constant, and it is thus possible to make use of the figures in computing the effects of adverse seasons in the different Districts. When combined with the age statistics of the Census, they show that severe famines, such as that of 1876-8, tell most upon the very young and the very old, and upon males more than upon females, and that their effects are not confined to the deaths directly caused by privation, but are clearly traceable in a marked decrease in the birth- rate due to the weakening of the reproductive powers. They also show that the rate of infant mortality is extremely high, and that both sexes are considerably shorter lived than in European countries.

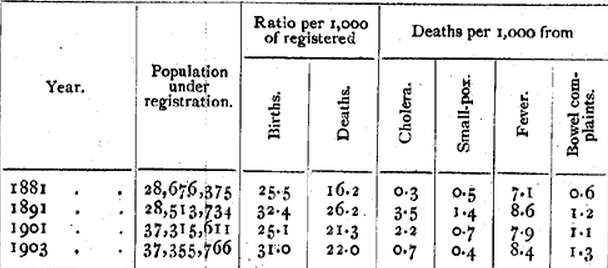

The subjoined table gives the birth- and death-rates (as registered) in the Presidency as a whole in recent years, and the mortality per T,ooo from certain diseases : —

It will be seen that the deaths caused by cholera and small-pox were comparatively few ; and credit for this is due to the Sanitary and Vaccination departments, which, by introducing drainage and water- supply schemes in municipalities, by improving the sanitary methods of the smaller towns, and by adding steadily year by year to the total number who are protected by vaccination, have done much to abate the virulence of two diseases which were once the scourge of the people. The deaths returned as due to fever include many of which the_real causes have not been properly diagnosed. The seasonal fever which occasions such heavy mortality in Northern India is hardly known in the South. Plague has not as yet succeeded in gaining the same foothold in Madras as in other Provinces. It has been worst in the Districts of Anantapur, Bellary, North Arcot, and Salem, all of which adjoin Mysore territory, where it has been very prevalent. The methods of combating plague have consisted chiefly in the temporary evacuation of infected villages and the thorough disinfection of the buildings within them. The people are at length beginning to realize the advantages of these measures.

In 1 90 1 there were 545,000 more females than males in the Presidency, or 1,029 of the former to every 1,000 of the latter; but in seven Districts — Kistna, Nellore, Cuddapah, Kurnool, Bellary, Ananta- pur, and Chingleput — which form a compact block of country in the centre, there always exists a preponderance of males which has never been satisfactorily explained. It cannot, for several reasons, be entirely due to the omission of women at the enumerations, nor to the migration to this area of large numbers of men. It is noticeable that in the large towns generally the proportion of women is lower than in rural areas, the reason being that the labour market of these places attracts the able-bodied men of the surrounding country.

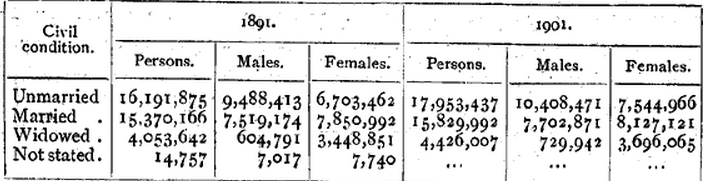

As in other parts of India, the three distinctive features of the statistics of marriage in Madras are its universality, the early age at ' which it takes place, and the high proportion which the number of widows bears to that of widowers. As is well-known, every Hindu desires a son to light his funeral pyre when he dies ; early marriage is encouraged by the example of the Brahmans, and by the difficulty of procuring brides and bridegrooms which the numerous prohibited degrees of marriage involve ; and the practice of the upper classes in the matter has caused it to be considered irregular for a widow to remarry.

Consequently, while in England and Wales, according to recent figures, 41 per cent, of the males and 39 per cent, of the females over the age of 15 are unmarried, in Madras in 1901 the corresponding figures were only 25 and 15. In the former country not one male or female in 10,000 under the age of 15 is married or widowed, while in this Presidency i per cent, of the boys and 9 per cent, of the girls under this age had entered into the bonds of matrimony : and while in England and ^^'ales there are 231 widows to every 100 widowers, in Madras there were 506. Among Musalmans and Christians, how- ever, these three distinctive features are much less pronounced than among Hindus, neither adult marriage nor widow remarriage being discouraged by their faiths ; and moreover a perceptible improvement in the degree to which all three of them prevail among Hindus, and even among Brahmans, is at length visible in the 1901 census figures.

The statistics of civil condition at the last two enumerations are appended : —

Owing, probably, to the former prevalence of polyandry, inheritance on the West Coast is usually through the mother. Polyandry, though now extremely rare, survives there still, and also among two or three Hindu castes elsewhere. Polygamy is permitted to both Hindus and Mu.salmans, but financial reasons restrict its practice. Divorce is freely allowed among Musalmans, but with Hindus is customary only in the lower castes.

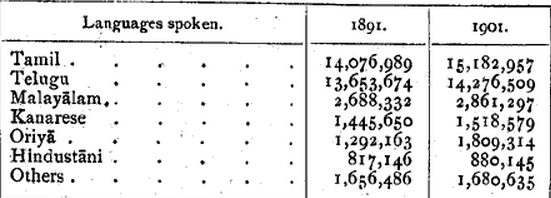

The most noticeable point about the languages of the people is the preponderance of those which belong to the Dravidian family. Over 91 per cent, of the population speak vernaculars of this family, while in India as a whole the percentage is only 20. The statistics of the last two census years are given below :—

The first four languages shown are Dravidian. Tamil is the tongue of the southern Districts of the east coast, Telugu that of the northern, Malayalam that of the west coast District of Malabar, while Kanarese is spoken in the upland regions bordering on Mysore, and is also the official language in South Kanara. Oriya is almost confined to the two northernmost Districts of Ganjam and Vizagapatam, and Hindustani is the vernacular of the Musalmans of purer extraction. Marath! and its dialect Konkan! are spoken by the considerable colonies of Marathas whom the various invasions of that race have planted in the Presidency (those in Bellary and Tanjore are instances), or who have overflowed into South Kanara District from Bombay. These seven languages are the only ones which have a written character and (except Konkani) a literature of their own, though some of the others borrow characters for use in writing. Their wriiten idiom generally differs very greatly from that used in the everyday speech of the masses.

In the hill and forest tracts are found several languages which survive in consequence of the geographical isolation of those who speak them. In the Agencies of the three northern Districts, Khond, Savara, Gadaba, Koya, and Gondi are spoken by the tribes from which they take their names ; on the Nilgiri plateau the Todas, Kotas, and Badagas each speak a language which is not found elsewhere ; the dialects of Kurumba, Kasuba, and Irula are used by sections of certain castes which still live in the hills, though their brethren in the low country have dropped them in favour of the better known tongues ; and the foreign gipsy race of the Kuravans or Yerukalas, like gipsies elsewhere, cling to their own patois wherever they roam.

The result of all this is an extraordinary diversity of tongues. In only seven Districts of Madras do as many as 90 per cent, of the people speak the same language, while in as many as four not even 50 per cent, of them speak the same language. In South Kanara five different ^•ernaculars — Tulu, Malayalam, Kanarese, Konkani, and MarathI — are spoken by at least 2 per cent, of the population ; in the Vizagapatara Agency six : namely, Oriya, Khond, Telugu, Savara, Poroja, and Gadaba ; and in the Nilgiris eight : namely, Tamil, Badaga, Kanarese, Malayalam, Telugu, Hindustani, English, and Kurumba.

The exigencies of space preclude any but the most general reference to the very many castes, tribes, and races of the Presidency. The 1 90 1 Census Report distinguished 450 communities of all degrees of civilization and enlightenment, from the Brahmans, the heirs to systems of religion and philosophy which were already old when the Romans invaded Britain, down to the Khonds of the Agency tracts, who within recent memory practised human sacrifice to secure plentiful harvests. The great majority are of Dravidian stock, and have the medium stature, the unusually dark (almost black) skin, the curly (not woolly) hair, the high nasal index, and the dolichocephalic type of skull which distinguish that race. In the Kanarese country, however, brachy- cephalic heads are common. A systematic Ethnographic Survey of the Presidency is now in progress.

Of the Hindu castes of Madras the five largest are the Kapus (2,576,000 in 1901), the Pallis (2,554,000), the Vellalas (2,379,000), the Paraiyans (2,153,000), and the Malas (1,405,000). The traditional occupation of all these (though the Pallis are less conservative than the other four) is agriculture, the Kapus and Vellalas being cultivators of their own land, while the others are farm-labourers. Next in numerical strength come the Brahmans (1,199,000), whose traditional calling is that of priest and teacher. Proportionately to the Hindu and Animist population generally, Brahmans are most numerous in the Districts of South Kanara, Ganjam, and Tanjore, and least so (only 15 in every 1,000) in the Nllgiris and the three Agency tracts.

But these large communities are by no means homogeneous through- out. They are divided and subdivided into endless sub-castes, which keep severely apart from one another and usually decline to intermarry or even to eat together. Nor is it the case that they all adhere to their traditional occupations. Census statistics show that one-fourth of the Paraiyans and 1 2 per cent, of the Malas have so far risen in the world as to become occupiers and even owners of land, instead of continuing to be predial serfs, while of the Brahmans 60 per cent, have left their traditional callings for agriculture, and others have even taken to trade.

These facts are not, however, an indication that the bonds of caste are weakening. In the all-essential matter of marriage their influence is perhaps becoming stronger, and the limits within his sub-caste outside which a Hindu may not take a bride are narrowing rather than expanding. A sign of the many disabilities which caste restrictions still impose is the energy with which a number of Hindu communities are endeavouring to improve their position in the scale accorded to them by their co-religionists. The Brahmans are the acknowledged heads of Hindu society, and their social customs are therefore con- sidered to be the most correct. A caste, or a subdivision of a caste, which desires to improve its position, will frequently, therefore, imitate Brahman ways as far as it dares, quitting callings considered degrading, taking to vegetarianism, infant marriage, and the prohibition of widow remarriage, inviting Brahmans of the less scrupulous kinds to officiate at its domestic ceremonies and remodel them in partial accordance with Brahmanical forms and ritual, and changing its name for one with less humiliating associations. Pretensions of this kind are seldom, however, meekly admitted by the superiors or equals of the aspiring community, or even by their inferiors.

The most notable recent protest against such innovations was the Tinnevelly disturbance of 1899, occasioned by the Maravans' refusal to admit the claims of the Shanans (who by tradition are toddy-drawers and so are supposed to carry pollution) to be Kshattriyas and to enter Hindu temples. Revolts against the traditional decrees of caste are, however, more often silent and gradual than open and avowed. The usual course of events is for a few families of a sub-caste who have risen in the world to hold aloof gradually from their former equals, to adopt some of the Brah- manical usages, and to look higher than before among the other subdivisions of the caste for brides for their sons and husbands for their daughters. In this way new sub-castes, and even new castes, are constantly originating.

The Musalmans of Madras are of three main classes^firstly, immi- grants from outside, or their descendants ; secondly, the offspring of these by Hindu women of the country : and thirdly, natives of the country who have gone over to Islam. It is not, however, possible to give the relative strength of these groups, as members of the last two of them frequently call themselves by the tribal names which in strictness belong only to the first. The ISIappillas and Labbais, how- ever, who are admittedly outside the first group, number 907,000 and 407,000 respectively, while the three most numerous tribes included within the first group — Shaikhs, Saiyids, and Pathans— number 787,000, 152,000, and 95,000. The religious and social observances of the mixed races partake largely of the forms current among Hindus, and even those of the purer stock are tinged by Hindu influences.

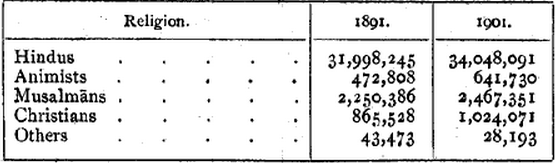

Of every 100 people in the Presidency, 89 are Hindus, 6 are Musalmans, 3 are Christians, and 2 are Animists : that is, worshippers of souls and spirits not included among the gods of the Hindu pantheon. Jains number only 27,000, most of them being found in South Kanara and North and South Arcot ; Parsis, 350 ; and Buddhists, 240. The numbers of the followers of the chief religions according to the last two enumerations are given below : —

Hindus preponderate enormously. If Animists be included with them (and the line of differentiation between the two is ill defined), they constitute 80 per cent, of the population of every District except Malabar, and as much as 97 per cent, in the three northern Districts of Ganjam, Vizagapatam, and Godavari. Their preponderance is, however, slowly declining, as they continue to increase less rapidly than either the Musalmans — who are apparently more prolific and certainly more given to proselytizing — or the Christians. By sect, , most of them are followers of Vishnu or Siva, the former predominating in the Telugu country and the latter in the extreme South. In the Western Deccan a large number belong to the sect of Lingayats, the members of which reverence Siva and his symbol the iingam, reject the claims of Brahmans to religious supremacy, and affect to disregard all distinctions of caste.

Musalmans are proportionately most numerous in Malabar and in ihe Deccan. The former District contains more than one-third of the whole number of this faith in the Presidency, the majority being of the race of Mappillas, whose fanatical outbreaks have given them an unenviable notoriet\\ Nearly all the Musalmans of Madras are Sunnis by sect. The few notable mosques which they have erected are adaptations, tinged with Hindu influence, of the styles prevalent in Northern India.

The rapid advance in the numbers of the native Christian population has been a marked feature in recent years. Since 1871 they have increased by 99 per cent., compared with an advance in the population as a whole of 22 per cent. : that is, they have multiplied between four and five times as fast as the people generally. Most of the converts are drawn from the lowest classes of society ; but they have made excellent use of the opportunities placed before them, and by their educational superiority and their manner of life are earning for them- selves a constantly improving position. Native Christians are pro- portionately most numerous in Tinnevelly and South Kanara. The total Christian population of Madras now numbers over a million, of whom only 14,000 are Europeans and 26,000 Eurasians. Of this total, 62 per cent, belong to the Church of Rome, 14 per cent, to the Anglican conmmnion, and 12 per cent, are Baptists. The only other sects largely represented are Lutherans and Congregationalists.

The Presidency includes three Protestant Bishoprics, those of Madras, Madura and Tinnevelly, and Travancore and Cochin, while the Roman Catholic Church is represented by an Archbishop and three Bishops, those of Mylapore, Vizagapatam, and Cochin, besides missionary bishops. The Syrian Church on the \\e?,i Coast has a separate organization.

A history of the Christian missions in Southern India would fill many pages. Excluding the legendary visit of St. Thomas the Apostle, the earliest mission was that of the Portuguese Franciscans to the AV'est Coast in 1500. The Jesuits began their labours in 1542, their first missionary being St. P'rancis Xavier, who worked in Tinnevelly and was buried at Goa in 1553. In 1606 Robert de Nobili founded the famous Madura Mission, to which also belonged De Britto (martyred in 1693) and Beschi, the great Tamil scholar. The Society of Jesus was suppressed in 1773 and not re-established till 1814, and during those years the missions languished. Persecution was also common, Tipu Sultan, for example, forcibly circumcising 30,000 of the West Coast (Christians and deporting them to Mysore. At the present time contributions are received from all parts of Europe for the support of the Catholic missions, and they are controlled directly by the Pope through missionary bishops delegated by him.

Of Protestant missions, the first was the Danish Mission at Tranquebar, which was established by Ziegenbalg in 1 705. Swartz and Rhenius both belonged to this. It was nmch helped in its early days by the English Societies for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge and for the I'ropagation of the CJospcl. The former sent out its first missionary in 17^8. The London Missionary Society followed in 1S04, and the Church Missionary Society ten years later. The Wesleyan Missionary Society began operations in 1818, and the American Madura Mission and the Basel Evangelical Mission in 1834. The latter has several branches on the West Coast, at which its adherents are occupied in the industries of printing, weaving, and tile-making under lay helpers. Later missions are the Baptist Telugu, the Free Church of Scotland, the Leipzig and the American Evangelical Lutheran Missions, the Arcot Mission of the Reformed Church in America, and the Cana,dian Baptist Mission.

The most noticeable point about the census statistics of the occupa- tions of the people is the rural simplicity of the callings by which the large majority of them subsist, and the rarity of industrial occupations other than weaving. No less than 69 per cent, of the population live by the land. Of these, more than 95 per cent, are cultivators, tilling land which they either own or rent from others. Of these cultivators, 72 per cent, farm land which is their own property, or, in other words, are peasant proprietors. Next to agriculture, but after a very long interval, the commonest occupations are those connected with the preparation and sale of food and drink, which support 7 per cent, of the population, and those relating to textile fabrics and dress, which include all the wea\ers and employ 4 per cent, of the people.

The various Districts differ little among themselves in the occupations which their inhabitants follow. The three Agency tracts and South Arcot are the most essentially agricultural areas ; but, excluding the exceptional cases of Madras City and the Nllgiris, the percentage of the population which lives by the land is fairly uniform, ranging from 62 to 75. Even in those Districts where this percentage is low, it is kept down merely by the unusual number of those who subsist by such callings as wea\ing, toddy-drawing, fishing, and so on, and not by the occupation of any considerable proi)ortion of the people in employment which is strictly speaking industrial. In the larger towns agriculture is naturally not the main occupation. The provision and sale of food, drink, and dress take the lead ; and next come money-lending, general trade, and callings connected with the transport and storage of mer- chandise. Even in towns, however, industrial occupations proper fail to employ any large proportion of the people.

Musalmans and the lower classes of Hindus eat meat, except that the former will not touch pork and that only the lowest castes of the latter will eat beef. The upper classes of Hindus are strict vegetarians, avoiding even fish and eggs. Alcohol is forbidden to Muhammadans and the higher castes of Hindus. Rice is the staple food of the richer classes, and yogi, canibu, and cholam the usual diet of the others. Pulses of various kinds are combined with all of these, and flavouring is obtained by the addition of sundry vegetables and a number of (often pungent) condiments. Nearly all classes chew betel.

The dress of the people varies with their religion and caste, and moreover differs in different localities. Speaking very generally, that of the Hindus consists of a waist-cloth and a turban. Well-to-do persons add a cloth over the shoulders. The educated classes have taken to coats, and sometimes trousers and even boots, but never use a hat in place of a turban. Musalmans wear trousers and jackets, and a turban wound round a skull-cap or fez. Hindu women usually dress in one very long and broad piece of cotton or silk which, after being wound round the waist, is passed over one shoulder and tucked in behind. Under this is often a tight-fitting jacket with short sleeves. Musalman women wear a petticoat and a loose jacket. Women never wear any head-dress, or anything on their feet.

Houses vary in degree from the one-roomed, mud-walled, thatched- roof hut of the labouring classes to the elaborate dwelling of the rich money-lender or landowner. The ordinary house contains a central court, surrounded by various rooms and opening by one door into the street. On the street side is usually a veranda, which is not considered to be part of the house and so can be used by strangers who would pollute the dwelling if they penetrated farther. In the Deccan there is usually no court and no outer veranda, and the roofs are flat. The members of one family, even if married, frequently live together and hold all their property in common. The present tendency, however, is for these joint families to break up and live separately.

Musalmans always bury their dead, and the same practice is usually followed by the lower castes of Hindus. The upper castes usually burn them, but high priests and other saintly persons are buried. In many communities curious exceptions are practised — lepers and pregnant women, for example, being buried.

Excepting English importations, games and amusements are few. Cock- and quail-fighting (though discouraged by the authorities) are popular in places, and cards, chess, and games of the ' fox and geese ' type are common. Strolling players, jugglers, and acrobats tour periodically through the country. A few castes organize beats for large game on general holidays.

The religious festivals of the South are legion. Perhaps the most important of those which are not merely local or connected with some special temple are the Ayudha PCija ('worship of implements') in October, when every one does reverence to the tools and implements of his profession — the writer to his pen, the mason to his trowel, and so forth ; the Dipavali (literally, 'row of lights ') in October or November ; and the Pongal (' boiling ') in January. At this last the first rice of the new crop is boiled in new pots. The cattle share in the festival, being allowed a day's holiday and having their horns painted with divers colours.

The Madras Hindu of the better classes has usually three names, e. g. Madura Srinivasa Ayyangar, or Kota Ramalingam Nayudu. The first of these is either the name of the village or town to which he belongs, as Madura ; a house-name (as Kota) adopted for a variety of reasons ; or the name of the man's father. The second name is that by which he is usually addressed, and is often that of one of the gods : while the third is the title of the caste. Among Brahmans, this third name further denotes the religious sect of its possessor, and sometimes even his nationality. Thus an ' Ayyangar ' is a Vaishnavite, an ' Ayyar ' a Saivite, and a ' Rao ' a Maratha Brahman. The labouring classes and women have usually only one name.

See also

For a large number of articles about Madras Presidency, extracted from the Gazetteer of 1908 (as well as other articles on Madras Presidency) please either click the 'India, Places' link (below, left) and go to India, Places (under M) or enter 'Madras Presidency ' in the 'Search' box (top, right).

Madras Presidency History, 1908

Madras Presidency Population, 1908