Mahatma Gandhi: ideology

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Vignettes

A

Oct 1, 2021: The Times of India

From: Oct 1, 2021: The Times of India

From: Oct 1, 2021: The Times of India

From: Oct 1, 2021: The Times of India

From: Oct 1, 2021: The Times of India

From: Oct 1, 2021: The Times of India

From: Oct 1, 2021: The Times of India

From: Oct 1, 2021: The Times of India

From: Oct 1, 2021: The Times of India

From: Oct 1, 2021: The Times of India

An abstemious life vs. an indulgent one

Sex, whisky, chocolates

Oct 2, 2019: The Times of India

(Interview to Margaret Sanger, Dec 1935, reproduced in The Penguin Reader, edited by Rudranghshu Mukherjee)

Key Highlights

"Love becomes lust the moment you make it a means for the satisfaction of animal needs, it is just the same with food," said the Mahatma

"If food is taken only for pleasure, it is lust. You do not take chocolates for the sake of satisfying your hunger," he added

Mahatma Gandhi wrote and spoke extensively on almost every subject under the sun. A sample of his views...

When both (man and woman) want to satisfy their animal passion without having to suffer the consequences of their act it is not love, it is lust. But if love is pure, it will transcend animal passion and will regulate itself. We have not had enough education of the passions. When a husband says, ‘Let us not have children, but let us have relations,’ what is that but animal passions? If they do not want to have more children they should refuse to unite. Love becomes lust the moment you make it a means for the satisfaction of animal needs, it is just the same with food. If food is taken only for pleasure, it is lust. You do not take chocolates for the sake of satisfying your hunger.

You take them for pleasure and then ask the doctor for an antidote. Perhaps you tell the doctor that whisky befogs your brain and he gives you an antidote. Would it not be better not to take chocolates or whisky.

The Bhagavad Gita

Influence of Gandhi

Anup Taneja, January 30, 2023: The Speaking Tree

Gandhiji had a unique faith in the ultimate goodness of man, a faith in the great potentialities of humanity and a faith that, notwithstanding all his limitations, weaknesses and violence in nature, man will someday rise to great spiritual heights. It was this belief that motivated him to render selfless service to humanity through the path of non-violence and the path of change of heart. His satyagraha was a weapon chiefly intended to serve humanity; the basic qualification of an ideal satyagrahi was a living faith in love and living faith in God. To quote him: “He must have a living faith in non-violence. This is impossible without a living faith in God.

Without it, he won’t have the courage to die without anger, without fear and without retaliation.” Being a man who reposed unconditional trust in God, Gandhi was totally fearless. He declared: “For many years I have accorded intellectual assent to the proposition that death is only a big change in life and nothing more; it should, therefore, be welcome whenever it arrives.” The question is: Where did this unique fearlessness and indomitable courage, his ever-readiness to lay down his life for truth and just cause, come from? It would not be wrong to say that the teachings of the Bhagwad Gita completely transformed his life. While meticulously going through the Gita, Gandhi discovered that its highest ideal was anasakti, non-attachment. He explains the concept of anasakti in the Gita by making two general statements: i) ‘not one embodied being is exempted from doing works’; and ii) ‘it is beyond dispute that all action binds’. The implication behind these statements is that none of us can escape action; it is the demand of nature that we must engage in action. Also, an action cannot be performed in isolation; one action will definitely require that further actions are performed and thus a vicious circle of bondage is created. The question is: How to escape from this bondage?

According to Gandhiji, surrendering oneself to the Divine Will unconditionally is the best course of action. He condemned the system of sannyasa in the form of cessation of all actions, primarily because it is not action as such that binds the doer, the motive with which an action is performed is the main factor. He opined that it is not desire that vitiates the action, but selfish desire, the desire for fruit; and if an end is put to this selfish desire, the action performed will become a noble act and won’t be binding. Thus, according to Gandhiji, the concept of renunciation in the Gita never implied absence of purpose; it only implied absence of purpose meant for self-benefit. Every action that one performs ought to be governed by some motive because no action could be performed in an abstract manner. That motive, however, should be to realise one’s Inner Self, the silent witness that keeps observing constantly all the activities of the mind. One who performs his duties with full dedication, with an attitude of surrender, becomes worthy of Self-realisation, the ultimate goal of human life.

Economic philosophy

An overview

Oct 2, 2021: The Times of India

Author Rajni Bakshi writes: "Gandhi’s asceticism in later life tends to obscure the fact that he often reminded people that he is a “vanika putra”, the son of a baniya (merchant)." In another context, Gandhi’s American admirer [and journalist] William Shirer writes: "There was something of the banian trader in Gandhi, reflecting the caste from which he came"; and Gandhi himself remained a supporter of the caste system, although he did hedge himself even as early as in 1921, when he wrote in Young India as follows: "I believe in the varnashrama dharma in a sense, in my opinion, strictly Vedic but not in its present popular and crude sense."

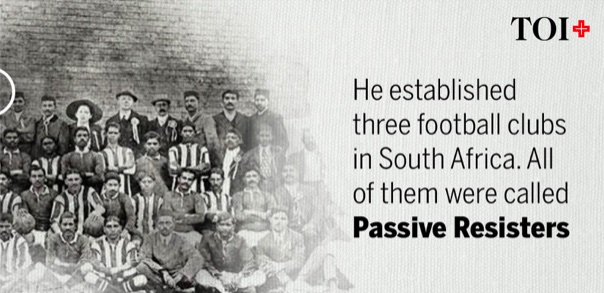

Gandhi’s attempt at a nuanced distinction between the caste system and the so-called traditional varnashrama dharma remained with him all his life. Gandhi’s positive approach to business, trade and wealth may have been in part a function of his caste origins. It was also reflected in many of his actions. He went to South Africa as an attorney for Gujarati Muslin merchants who themselves originally belonged to the Bania caste and were relatively recent converts to Islam. In South Africa, two of his important associates, Polack and Kallenbach, were Jewish businessmen.

Back in India, Gandhi was quite close to Ambalal Sarabhai, who provided funds for Gandhi’s ashram in Ahmedabad. Gandhi was also close to the Marwari Bania businessman Jamnalal Bajaj, who was sometimes referred to as "Gandhi’s fifth son". Gandhi maintained very close contacts with businessmen like Ghanshyamdas Birla.

In fact, what is today called the Tees January Marg in Delhi was the site of Birla House. It was here that Nathu Ram Godse shot the Mahatma. Gandhi was Birla’s guest on that fateful 30th day of January in 1948. Gandhi took positive delight in the business successes of India and Indians. He was ecstatic when the Scindia Steam Navigation Company launched a ship under an Indian flag. The evolution of the caste system, trade and finance networks, and organised charity in Gandhi’s home state of Gujarat, clearly influenced Gandhi in the development of his own admittedly idiosyncratic, but equally insightful and powerful views in the field of political economy.

The historian Chhaya Goswami points out that in Kachchh, the king always appointed a merchant, usually of a Bania caste like the Bhatias, as his diwan or prime minister. It could also quite easily be a merchant from a traditionally peasant or artisan caste. This contrasts with what obtains in other parts of India, where the ministers were usually Brahmins. The rulers of the different states of Gujarat saw the merchant elite as their allies. They respected the office of the Nagarsheth, who was the leader of the merchant community across caste and religious divides. Interestingly, according to Goswami, the Nagarsheth acted as a trustee of the interests of his fraternity. The Panjrapole, the animal hospitals that were dear to the hearts of the vegetarian Jain and Vaishnava Banias of Gujarat, were run as charitable trusts.

The famous Anandji Kalyanji Trust, which manages several Jain temples across India, is said to have been established between 1630 and 1640, although accurate recording goes back only till 1720. The chief trustee of the Anandji Kalyanji Trust for over 50 years, Kasturbhai Lalbhai, was a lifelong friend and associate of Gandhi. One can make the case that the Bania-trustee tradition of Gujarat was very much part of Gandhi’s own Bania-Vaishnava world view, and over the years helped him refine his ideas of trusteeship.

Gandhi the lawyer It is important to remember that Gandhi was a lawyer trained in English common law traditions. It stands to reason that, along with his acquaintanceship with the Magna Carta, the great charter guaranteeing political liberties to English citizens, which had the unintended consequence of making him a lifelong seditionist, he picked up, among other things, a sound understanding of the legal concept of trusteeship at the Inner Temple, one of the four Inns of Court in London.

A peculiarity that is central to trusteeship is that the trustee does not act in his or her own interest, but in the interests of another legal person who is known as the beneficiary. This is a foundational idea, which Gandhi developed further in ways that were both brilliant and idiosyncratic, pretty much what one would expect from the Mahatma! Trusteeship is a concept fairly unique to English common law. It does not exist in continental civil law and Code Napoleon jurisdictions. During an illuminating conversation, Girish Dave, himself a feisty Gujarati lawyer with an impish Gandhian sense of rebellion about him, told me that had Gandhi trained in France, which is a civil-law country, he might have been less committed both to non-violent Constitutional progress and to trusteeship. Trusteeship is considered one of the high points of English common law and almost as a unique contribution in the broader area of civil and commercial jurisprudence.

Closely associated with the idea of trusteeship is the idea of what constitutes ‘fiduciary responsibility’ and abuse thereof. The fiduciary notion assumes that the trustee is not selfishly pursuing the trustee’s own interests, but is keeping in mind the interests of the beneficiary. The trustee acts on behalf of ‘another person’ and is duty-bound to protect and enhance the interests of the ‘other’. The moralist in Gandhi clearly saw the relationship between this legal concept and the ethical imperative for unselfishness. A violation of one’s fiduciary responsibilities as a trustee is contrary to law and can invite legal sanctions and penalties. It was Gandhi’s genius not to just stay focused on the illegality, but also highlight the immorality of neglect of fiduciary duties.

Gandhi pointed out that Hindu tradition stresses not only ‘paapa’ (sin); the act of being a good trustee could also lead to ‘punya’ (meritorious action, or the opposite of sin). Gandhi was very fond of and extremely influenced by the Gospels of the New Testament. Arguably, he quotes more from the Gospels than from any other source. Among the Christian denominations, the Quakers caught his attention, and Gandhi developed a keen interest in their philosophy. The Quakers were a group of anti-establishment Christians who were pioneers in a variety of fields: opposition to slavery, support for Irish and Indian nationalism and support of principled pacifism.

As an aside, it is interesting that Gandhi’s first public speech during his Round Table Conference visit to England was in front of Quakers at the Friends Meeting House in Euston Road in London. The Quakers were a Christian denomination whose commitment to absolutist standards of non-violence is well known. What is not so well known is that Quakers had ideological concerns in the area of inheritance, including inheritance of wealth. While several Quakers opposed the idea of humans being born into bondage as slaves, others have repeatedly looked upon inherited wealth as being problematic. Gandhi too was extremely uncomfortable with inherited wealth. He was quite emphatic in Harijan in 1942 when he wrote: "Personally I do not believe in inherited riches".

Excerpted with permission from Economist Gandhi: The Political Economy of the Mahatma, Its Roots and Relevance (published by Penguin India)

Education

Should be Holistic

MS Kurhade, Dec 19, 2019 Times of India

MK Gandhi is rightly regarded as one of the greatest advocates of education for all. A vital aspect of Gandhiji’s thoughts on education was his focus on social and spiritual education. He dismissed any education which did not teach human values. He said, “An education which does not teach us to discriminate between good and bad, to assimilate the one and eschew the other, is a misnomer.”

Gandhiji addressed students directly and appealed to them to develop a strong moral character: “The miasma of moral impurity has today spread among our school-going children and, like a hidden epidemic, is working havoc among them. All your scholarship, all your study of the scriptures, will be in vain if you fail to translate their teachings into your daily life.” Reminding students of the necessity of discipline and building one’s character, Gandhiji said, “Students should be, above all, humble, and correct ... The greatest, to remain great, has to be the lowliest by choice.” It is important to distinguish between religious education and spiritual education. While Gandhiji felt that religious education should remain the “sole concern of religious associations”, for him, secular “spiritual training” was “education of the heart”.

According to Gandhiji, the effective means of development of personality and character is the study of one’s religion. He emphasised such traits as the spirit of self-sacrifice, social service, ahimsa and brahmacharya. True religion means an abiding faith in the absolute values of truth, love and justice. So, he recommended instruction in the universal essentials of religion and training in the fundamental virtues of truth and non-violence as the very basis of religious education. In fact, Gandhiji wanted that every child should respect all religions and this should get reflected in his daily conduct.

The Gandhian aim of education is human transformation rather than simply to acquire information. Today ethics, morality, compassion and such values are accepted in theory, but are difficult to implement in practice, whereas Gandhiji thought that the implementation of these values in practical life, is the very core of education.

Thus, it is evident how Gandhiji’s new vision of education combined the practical with the spiritual, local with universal. He wrote, “The function of Nayee-Talim is not to teach an occupation, but through it to develop the whole man.” For him, this meant the advancement of all faculties and elements within us. He said, “By education I mean an all-round drawing out of the best in the child and man – body, mind and spirit.” Holistic education, integrating past traditions with the future of the nation, beginning with the individual and ending with society and the universe as a whole, formed the culmination of Gandhiji’s thoughts on education.

This is where Gandhiji’s philosophy of education steps in at the present crisis facing the world. What we most require now is the kind of education that fosters love, develops character and provides an intellectual basis for realisation of peace and empowers learners to contribute to and improve society.

The relevance of Gandhi comes from the basic premise that everything he preached, he practised. His life was open and one can draw inspiration for all the myriad dimensions of everyday life simply by learning from his life, thoughts and writings, particularly in this special sesquicentennial year of Gandhiji’s birth.

Inspirations

The four basic strands of his ideology

Sep 24, 2019: The Times of India

(From: Kaka Saheb Kalelkar’s Stray Glimpses of Bapu)

4 questions Gandhi asked of himself, and of all of us

Historian Judith M Brown explains the contemporary relevance of the Mahatma through answers to questions Gandhi searched for all his life

150 years after Gandhi’s birth there are many Gandhis, in India and worldwide. Diverse people and groups have valued and used some of his ideas and practices, or used his name to grace their own projects. Sometimes he has been deployed in support of causes which he would not have recognised. In a real sense, he has become “global property”.

If we turn to the historical Gandhi, to a man living in a particular time and place, working in a specific social and political context, I would argue that his real relevance in India and in the wider world today is that he had the depth of character and vision to pose fundamental questions for modern men and women: questions about the value of the human person, the proper nature of public identity, and the right ways to live in community and to deal with inevitable disagreements and conflict. This is in contrast to those “Gandhians” who would argue that he provided “answers” relevant in any situation. Let me suggest just four of these major questions which Gandhi in his own time in South Africa and India was to ask — of himself and of those around him.

1 What is religion?

This may seem a strange question to start with. But Gandhi’s answer to this question was very different from the answers which would have been given by many of his contemporaries in India and beyond. Moreover, it had fundamental implications for his understanding of the significance of all human persons, and for his commitment to enter public life to serve others, and to work in such a way as to preserve their dignity and autonomy. For Gandhi, religion was not a clearly packaged and labelled set of beliefs and practices; neither was it a communal or semi-tribal identity. It was a pilgrimage in search of truth, a lifelong searching for God as truth rather than for a divinity which could be described in any simpler way. It is significant that he subtitled his partial autobiography, written in the mid-1920s, as “The Story Of My Experiments With Truth.” This understanding of religion set him at odds with contemporaries for whom religion was a particular orthodoxy of belief and practice, or the cement of specific socio-political identities. He believed that Truth resided at some deep level in every individual, and that consequently he was called to serve humanity, particularly those who were weak and disadvantaged in ordinary human terms. Other fundamental questions flowed from these assumptions.

2 What is the nature of political identity, particularly the ‘nation’?

This was an urgent question in the context of late colonial India. The nature of the family, of caste, region, community and nation were all under scrutiny in the final years of the empire as Indians contemplated the shape of their country and society after independence. Gandhi’s answer to these sorts of questions was rooted in his belief in the primacy of a common humanity which should override all other social and political connections. Consequently, he favoured small-scale communities where people knew each other face to face, and where it was more difficult to categorise people as ‘other’. As far as the Indian nation was concerned, he envisaged it as being made up of many of these small-scale communities. India was not to be defined by language or creed or even place of birth and heritage. What mattered in making “an Indian” was living in the subcontinent, making it one’s home, and valuing its ancient and complex civilization. The identity of the nation was urgent in his time because of the imminent departure of the British rulers, and increasingly violent controversies over the relationship between national and religious identity. The question is as significant as ever — in contemporary India, and in a global context marked by the rise of exclusive right-wing nationalisms, which would discriminate against minorities, particularly those created by immigration.

3 How should one conduct oneself in the practice of politics?

Gandhi recognised that disagreement and conflict are inevitable in human society and interaction between individuals and groups. If all people shared a common humanity then a crucial question for him was how to manage conflict, and particularly how to conduct oneself in the political arena when addressing differences and controversies. His answer to this question, forged over many years in public life in South Africa and India, was the multi-dimensional practice of non-violence or satyagraha. Conversion rather than coercion was his remedy for conflict.

Non-violent resistance to what was perceived as wrong was most likely to create long-term change in all the parties to a conflict, and would protect the integrity of all those concerned. In many ways non-violence was his most creative and long-lasting idea; though his life showed that in practice it was not the universal panacea for peaceful change which he had envisaged. Even though non-violent modes of public and political action often seem to have failed in his lifetime and beyond, his life and teaching raise the perennial question of the right ways to behave in the public arena.

4 The final question Gandhi raised, not least by his mode of life, was the broad one: how should one live?

This really coupled together several issues relating to the obvious inequalities between individuals and groups within India and also globally. It has taken on new urgency as we are increasingly aware of the impact of humankind on the environment as people and groups strive for ever-greater patterns of consumption. Gandhi is said to have uttered the powerful aphorism that “there is enough in the world for every man’s need but not for every man’s greed”. He also drew on his lawyer’s training in London to deploy the idea of “trusteeship” to denote how those who have more resources should consider and use them for the wider good.

His own lifestyle in the last 25 years of his life back in India is well known — and Gandhi was well aware of the publicity effect of his freely chosen poverty and simplicity in food, clothing and possessions. In his own lifetime, people commented on the effort and expense it took other people to “keep Gandhi poor”; and certainly an ashram life is not one to which most people are called. But the question he posed remains — how should we live? Our answers are critical for the future of our world — for the relationships between privileged and underprivileged within nations, for relationships between richer and poorer parts of the world, and for the very existence of our planet as a place fit for human habitation.

The writer is Emeritus Beit Professor of Commonwealth History in the University of Oxford. She has also written the book, Gandhi: Prisoner of Hope

When Tilak ‘Delayed’ Swaraj

In 1917, the first meeting of the Gujarat Political Conference was held at Godhra (Gujarat). Gandhi arrived on the dot as was his habit. The great Lokmanya Tilak had also been invited to the conference, but he arrived a little late. Gandhi received the Lokmanya with great respect and all the deference due to a national leader. But Gandhi could not desist from commenting that the Lokmanya was half an hour late, and if Swaraj was delayed by half an hour, he would have to bear the blame for it.

Rajchandra, Shrimad / Raichandbhai

Anup Taneja, October 2, 2020: The Times of India

In his very first meeting with Shrimad Rajchandra, also known as Raichandbhai – a Jain poet, mystic and philosopher – in July 1891, MK Gandhi was convinced that he was a man of great character and erudition. What appealed to Gandhi most about Rajchandra was his spotless character, wide knowledge of scriptures, his burning passion for Self-realisation and above all, his ability to remember and attend to many things simultaneously.

Despite being engaged in the business of pearls and diamonds, Rajchandra yearned to see God, face-toface. Gandhi writes: “The man who, immediately on finishing his talk about weighty business transactions, began to write about the hidden things of the spirit, could evidently not be a businessman at all, but a real seeker after Truth.” According to Gandhi, Rajchandra was the very embodiment of non-attachment and renunciation; he considered the whole world as his family and his love extended to all living beings. Gandhi imbibed from Rajchandra his lessons for self-improvement and on Truth and non-violence.

Long before Gandhi came to be called as a ‘Mahatma’, he faced a spiritual crisis in South Africa when his Christian and Muslim friends were pressing him to convert to their faiths. During this crucial phase Gandhi sought advice from his spiritual guide, Rajchandraji, in a letter which contained some questions relating to spiritual matters. One of the questions raised by Gandhi was: “If a snake is about to bite me, should I allow myself to be bitten or should I kill it, if that is the only way in which I can save myself ?”

Rajchandra wrote back saying that though he would hesitate to advise that he should let the snake bite him, yet, at the same time, it was important to understand that after having realised that the body is perishable, where lies the justification in killing the snake (that clings to its body with love) and in protecting the body that has no value for him?

Rajchandra further said that anyone who wants to evolve at the spiritual level should allow his body to perish in a situation like this. Even for a person who does not desire spiritual welfare, it would not be advisable to kill the snake; the reason being that this sinful act will result in severe punishment in the nether worlds. However, a person who lacks culture and character may be advised to kill the snake, but we should wish that neither you nor I will even dream of being such a person.

Little wonder that Rajchandra’s emphasis on truth, compassion and non-violence in every walk of life later crystallised as the fundamental tenets of Gandhism, which played a significant role in the Indian struggle for independence! The inner bond between Rajchandra and Gandhi initiated a brilliant new chapter, not only in their own lives, and in the history of Gujarat, but in the cultural, political and spiritual history of the entire nation.

Gandhi said, “Many times I have said and written that I have learnt much from the lives of many a person, but it is from the life of poet Raichandbhai, I have learnt the most and I must say that no one else has ever made on me the impression that Raichandbhai did.”

The writer is author of the book, ‘Influences that shaped the Gandhian Ideology’ published in 2020

Israel Palestine

Arjun Sengupta, Oct 3, 2024: The Indian Express

Gandhi’s most-quoted line on the subject, however, does not capture the complexity of his views on the matter. As the war in Gaza nears the one-year mark, here is what Gandhi had to say about the “very difficult question”.

Gandhi had deep sympathy for the Jewish people

Gandhi had deep sympathies for the Jewish people, who had been historically persecuted for their religion.

“My sympathies are all with the Jews… They have been the untouchables of Christianity. The parallel between their treatment by Christians and the treatment of untouchables by Hindus is very close. Religious sanction has been invoked in both cases for the justification of the inhuman treatment meted out to them,” Gandhi wrote in the Harijan article.

“The German persecution of the Jews seems to have no parallel in history,” Gandhi said. He expressed concern over Britain’s policy of placating Adolf Hitler (before World War II broke out in September 1939), and said that for the cause of humanity and to prevent the persecution of the Jewish people, even a war with Germany would be “completely justified”.

“If there ever could be a justifiable war in the name of and for humanity, a war against Germany, to prevent the wanton persecution of a whole race, would be completely justified,” he wrote.

Gandhi had a long association with the Jewish people; during his time in South Africa (1893-1914), most of his friends were Jewish. Notable among them were the likes of Hermann Kallenbach, who remained a lifelong associate of the Mahatma.

In her book Gandhi and his Jewish Friends (1992), Margaret Chatterjee wrote that Gandhi saw the East European Jewish immigrants in South Africa “as a group of people who, like Indians, were being victimised for no fault of their own… [They] became his closest friends and on whom he depended for his social and political work both in Johannesburg and London.”

But he had a problem with a Zionist state

Despite his sympathies for the Jewish people, Gandhi was not keen on a Zionist state. He believed that a call for a Jewish homeland would undermine the Jewish people’s cause to be treated with dignity, and as equals elsewhere in the world.

“If the Jews have no home but Palestine, will they relish the idea of being forced to leave the other parts of the world in which they are settled?” Gandhi wrote. He added that the Jewish claim for a national home afforded “a colourable justification for the German expulsion of the Jews”.

He wrote: “If I were a Jew and were born in Germany, I would claim Germany as my home even as the tallest gentile German may, and challenge him to shoot me or cast me in the dungeon; I would refuse to be expelled or to submit to discriminating treatment”.

Given the Holocaust (1941-45) that would begin soon, this view might sound naive; however, Gandhi was not alone in thinking this way.

He had, however, another reason to oppose a Jewish homeland, especially in Palestine.

“It is wrong and inhumane to impose the Jews on the Arabs…,” he wrote. “It would be a crime against humanity to reduce the proud Arabs so that Palestine can be restored to the Jews partly or wholly as their national home,” Gandhi said.

The Mahatma believed that the way the Zionist project was proceeding, with British support, was fundamentally violent.

“A religious act [the act of Jews returning to Palestine] cannot be performed with the aid of the bayonet or the bomb,” he wrote. Gandhi felt that the Jews could settle in Palestine only “with the goodwill of Arabs”, and for that they had to “forgo the British bayonet”.

A change of heart? Not really

Some have argued that Gandhi had a change of heart when it came to the question of Israel, and that his position on the issue changed significantly after the horrors of the Holocaust became known.

A conversation that he had with his biographer Louis Fischer in June 1946 is often quoted in this regard. Gandhi reportedly said: “The Jews have a good cause. I told (British Zionist MP) Sidney Silverman that the Jews have a good case in Palestine. If the Arabs have a claim to Palestine, the Jews have a prior claim.”

However, there is little evidence beyond Fischer’s writings that Gandhi indeed said that “Jews have a prior claim”. After a newspaper published an article about Gandhi’s seeming support for the Zionist cause (citing his conversation with Fischer), Gandhi issued a clarification in Harijan in July 1946.

“But for their [the Jews’] heartless persecution, probably no question of return to Palestine would ever have arisen,” he wrote in “Jews And Palestine”. “They have erred grievously in seeking to impose themselves on Palestine with the aid of America and Britain and now with the aid of naked terrorism,” he wrote.

Marital rape

Bapu advised son against marital rape

Radha Sharma, Oct 1, 2019: The Times of India

AHMEDABAD: Mahatma Gandhi was known as the father of the nation. But he could inspire many a modern men with his commitment to be a father and not a father-in-law to his four daughters-in-law.

In fact, in many letters he wrote to his sons, Gandhi championed the cause of respecting women. He counselled his sons to treat their life partners as not their slaves but equal partners. In fact, in one letter, Gandhi even counsels his son against marital rape advising conjugal bliss only with mutual consent.

"With your consent, I wish you to take a vow. You will maintain Sushila's freedom. You will not rape her for your carnal desires but establish conjugal relationship only with mutual consent," Gandhi wrote to his second-born son Manilal in a letter discussing ideal married life with prospective bride in Sushila.

Gandhi was a very vocal advocate for women's equality. "Treat your wife as a partner not a slave," Gandhi counselled his son Manilal.

The letters are documented in a book titled 'Jyan raho tyan mahekta raho: Putra ane putra-vadhuo prati Gandhiji' (Keep spreading fragrance wherever you are: Gandhiji towards his sons and daughter-in-laws) authored by Neelam Parikh, great-granddaughter of Mahatma Gandhi.

‘Coupling is to complete you’

Gandhi was father to four sons and their wives namely Harilal and Gulabben; Manilal and Sushilaben; Ramdas and Nirmalaben and Devdas and Lakshmiben.

Offering congratulations on engagement of his grand-daughter Manu with Surendra, nephew of his associate Kishorelal Mashruwala, Gandhi doled out advise to the couple, "You are becoming each other's friend and ally. The girls are not connected with you so that you can rule over them or make them do hard labour," he wrote. "The coupling is to complete the two of you. Both partners experience equality of heart, mind and soul. Do not ever put each other down but complete yourself.”

Panchayati Raj

‘Every village has to become a self-sufficient republic’

Rishika Singh, April 24, 2023: The Indian Express

A landmark law on Panchayati Raj institutions came into effect on April 24, 1993, for which the National Panchayati Raj Day is marked. Here’s what Gandhi said of village governance and why the act helped materialise some of his ideals.

Marking a landmark law that came into effect on April 24, 1993, the National Panchayati Raj Day was the day when the Constitution (73rd Amendment) Act, 1992, vested constitutional status on Panchayati Raj institutions. Prime Minister Narendra Modi will inaugurate a range of projects and schemes today under the “Inclusive Development” theme of Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav, celebrating 75 years of Indian independence.

The law on the governance of India’s villages was also a manifestation of one of Mahatma Gandhi’s central principles. He often championed the idea of a Panchayati Raj setup, where local people participate in the functioning of their villages – in improving the condition of schools, roadways and water bodies.

In fact, Gandhi stated that after Indian independence from British rule in 1947, he wished for the Congress Party to transform into a volunteer organisation consisting of panchayat-like units in all Indian villages to interact with villagers for achieving swaraj. We explain what Gandhi meant when he spoke about the concept and why the law was a milestone.

Also, the UPSC Civil Services Examination often asks questions about Gandhi and Gandhian principles in the Essay, Ethics and Polity papers. Moreover, Panchayati Raj is an important topic in General Studies II (in Polity syllabus), which has both basic and advanced questions. For example, in 2018, UPSC asked the following question in its Mains examination: “Assess the importance of the Panchayat system in India as a part of local government. Apart from government grants, what sources the Panchayats can look out for financing developmental projects?”

What was the context of Gandhi’s quote?

Gandhi’s full quote, from a 1946 issue of the Harijan magazine, reads: “Independence must mean that of the people of India, not of those who are today ruling over them… Independence must begin at the bottom. Thus, every village will be a republic or Panchayat having full powers. It follows, therefore, that every village has to be self-sustained and capable of managing its affairs even to the extent of defending itself against the whole world.”

In his various experiments against colonial forces and creating an alternative to their model of governance, Gandhi put forth values like ahimsa (non-violence) and satya (truth). But apart from ideology, he also gave practical steps for achieving true self-rule or swaraj. He said India must have panchayats, a setup where the village’s adults elect a council of five people and a head among them, as local representatives.

Although, Gandhi clarifies this does not mean not taking any help from the outside world, but simply that each person must be so capable as to take care of their own basic needs in life in harmony with nature and those around them.

This would mean contributing labour for public work like sanitation, growing food locally, creating a rotational force for guarding the village, ensuring education for all, wearing hand-spun khadi to promote local artisans, shunning intoxicants, etc.

Where does swarajya in villages fit in Gandhi’s ideology?

Gandhi said that in a structure composed of “innumerable villages there will be ever widening, never ascending circles. Life will not be a pyramid with the apex sustained by the bottom.” And so instead of a hierarchy of a powerful district or state or Centre, villages must be equal, important micro units from whom the Centre ultimately derives its power through coordination. This has also been termed “democratic decentralisation”.

He recognised the difficulties in achieving this, but added it was to be a template, saying, “If one man can produce one ideal village, he will have provided a pattern not only for the whole country, but perhaps for the whole world.” The idea also reflects his larger inclination towards preserving Indian traditions and resisting external forces.

What was the Constitution (73rd Amendment) Act of 1992?

Before the act, India’s Constitution only mentioned a two-tier form of government and local institutions found a mention only in Directive Principles of State Policy – which is not enforceable by courts or bound to be followed, only meant as a guiding document for governments.

With a lack of focus here, absence of regular elections, insufficient representation of marginalised sections like Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and women, inadequate devolution of powers (transfer from a higher level of government to the lower levels) and lack of financial resources from the state and the Centre were some issues plaguing village-level governance.

Several committees were constituted for studying these issues, such as the Balwant Rai Mehta Committee and the Ashok Mehta Committee, which gave important recommendations. In the late 1980s, then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi prioritised the issue and after cross-party support, the measure was finally passed. Being enshrined in law and an amendment to the Constitution meant these provisions could no longer be easily ignored. The 74th Amendment Act, passed in the same year, sought to look at local governance in urban areas and constituting municipal bodies.

What did the Act change?

As The Indian Express noted in its 2018 editorial on 25 years of the act, “The Panchayati Raj Act not only institutionalised PRIs [Panchayati Raj Institutions] as the mandatory third tier of governance, it transformed the dynamics of rural development by giving a say to a large section of the people — significantly, women — in the administration of their localities.” Here are some other key changes it brought:

- It said the state government may devolve powers for such bodies to implement schemes for economic development and social justice, authorise a Panchayat to levy, collect and appropriate taxes, duties, and tolls and provide for making such grants-in-aid to the Panchayats from the Consolidated Fund of the State – a major move to help fund them.

- It mandated women’s representation in one-third of the seats. Women now constitute more than 45 per cent of the nearly three million panchayat and gram sabha representatives in the country, standing in contrast to their representation in the current Lok Sabha, at 14 per cent. Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe groups were also mandated to be assigned seats in proportion to their presence in the population.

- A five-year term was fixed for representatives, with a procedure given for conducting timely elections.

- It also noted that the Governor of a State would constitute a Finance Commission to review the financial position of the Panchayats and then recommend to her what their requirements are, how they can be met, etc.

And how can the act be evaluated now?

Undoubtedly, the act has been instrumental in involving more and more people in the democratic processes at a grassroots level. As James Manor notes in The Oxford Companion to Politics in India, decentralisation generally results in more transparency between the government and the people, better grievance redressal and better information flow. Manor notes how civil servants can gain timely news about developing health concerns or outbreaks in rural areas, for example, to suggest intervention.

However, he also noted that many of the initial worries – having to do with finances, real devolution and genuine representation of marginalised groups – remain. Too often, these are dependent on the approach of the political parties in states or a reluctance to cede power.

Notably, the domain of local governments comes under the State List as per Schedule 7 of the Constitution. Manor explained that this meant, “The amendments had to suggest more things than they required of the states.” State governments’ varied responses have led to varying results of the act’s impact across India.

In 2013, former MP Mani Shankar Aiyar headed a committee titled ‘Towards Holistic Panchayat Raj’ on evaluating the act 20 years after it came into effect. He also noted some steps to rectify these problems in an article in The Indian Express, ranging from financial incentivisation of the states to encourage effective devolution to greater involvement of these bodies in district-level planning.

Philosophy of life

Buddhism

Lama Doboom Tulku, Mahatma Through The Eyes Of A Buddhist, October 2, 2018: The Times of India

MK Gandhi said, “Many Buddhists in Ceylon, as if by instinct, claimed me as their own. Undoubtedly, if the Buddhists of Ceylon and Burma, China and Japan would claim me as their own, I should appreciate that honour readily, because I know that Buddhism is to Hinduism what Protestantism is to Roman Catholicism, only in much stronger light, in a much greater degree.”

If we take out the various sects, cults, rituals and also fine philosophical distinctions from what is known to us as Hinduism today, what will remain is the fundamental teachings on good living, attitude and behaviour with fellow human beings and realisation of the final goal. There is no significant difference between Buddhism and Hinduism as far as these basic precepts are concerned. Another way of expressing this is to acknowledge that “Buddhism and Hinduism are two branches of same Bodhi Tree” as Morarji Desai said.

Gandhiji was born and raised a Hindu, and he avowed that denominational label all his life. Yet his intense engagement and relation with Abrahamic religions were personal, theological and pragmatic. He writes in his autobiography that he read Edwin Arnold’s ‘The Light of Asia’ with even greater interest than he did the Bhagwad Gita. “Once I had begun it, I could not leave off … My friends consider that I am expressing in my own life, the teachings of Buddha. I accept their testimony.” Gandhiji also said he was trying his level best to follow Buddha’s teachings. All Buddhists in the world today agree that Gandhiji lived Buddhism.

Followers of Buddhism are given five precepts: abandon killing, stealing, unwise and unkind sexual behaviour, lying and taking intoxicants including alcohol and recreational drugs. We can also draw a formula essentially based on Gandhiji’s life for ethical living: non-aggressive culture, truthfulness, moderation and sense of fairness to others.

Non-aggressive culture: There are three ‘doors’ of action and any action takes place through these doors. Among them, the mind is the first and foremost. But, it is not visible until it is expressed either through verbal or physical doors. Normally, verbal expressions such as harsh words or lie utterances precede harmful physical actions. Aggression is not only associated with muscle power but also money power and/or men power.

Culture of truthfulness: Gandhiji’s concept of Truth as God was in line with the Buddhist doctrines of Dharma Kaya. Ahimsa as a sense of identification with all creation, matches with the Buddhist practice of upekkha, equanimity. In everyday life, being truthful means not only abstaining from telling lies but also keeping promises.

Moderation: We must accept our limits and not expect to achieve high goals right from the beginning itself.

Fairness to others: Often we hear people asking whether such and such deeds are kalyan (meritorious) or akalyan (non-meritorious). You are actually asking whether you will suffer as a result of this or that act. To completely eradicate such self-minded attitude is too high a goal to achieve for an average person. What is possible is to gradually minimise thinking only of oneself; and not ignoring others and the environment.

I conclude with a prayer from Shantideva’s ‘Engaging in noble character’:

By the force of this merit of mine, May all living beings without an exception Abstain from all harmful acts; and Be engaged in righteous deeds, all the times.

Teaching the Bible

January 28, 2018: The Times of India

WHEN GANDHI TAUGHT THE BIBLE

…And saw it as wholly consistent with Hinduism, writes noted Gandhi scholar Tridip Suhrud

Gandhi first read the Gita as a student in London with theosophist friends — Bertram and Archibald Keightley — in Sir Edwin Arnold’s translation, The Song Celestial. Gandhi recalled in his autobiography that he was captured by Verses 62 and 63 of the second discourse.

‘If one Ponders on object of the sense, there springs Attraction; from attraction grows desire, Desire flames to fierce passion, passion breeds Recklessness; then the memory – all betrayed Lets noble purpose go, and saps the mind, till purpose, mind, and man are all undone.’

What awakened in Gandhi a religious quest and longing that was to govern his entire life henceforth was the message contained in these two verses — that the only way to be in the world was to strive to reach the state of brahmacharya. The Gita became a lifelong companion and a spiritual guide.

Later when Gandhi dwelled in the Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad, he decided to give a daily discourse on the Gita, hoping to elaborate on the incessant striving to lead his life by its ideals. On February 24, 1926 Gandhi gave the first discourse; by the time he concluded the lecture series on November 23, 1926 he had given 218 discourses on the Gita. Gandhi had been commenting on stray verses and deducing his own meaning from them, often leaving his co-workers confounded by his interpretation. They demanded that Gandhi also translate the Gita into Gujarati with notes. Thus, Gandhi began the Gujarati translation of the Gita so that the meaning he derived from it could be fully comprehended.

Gandhi rarely made a claim to originality and even rarer it was for him to claim literary merit for his writings. But while presenting his translation he made a claim that no translation had made thus far. ‘This desire does not mean much disrespect to other renderings. They have their own place. But I am not aware of the claim made by the translators of enforcing their meaning of the Gita in their own lives. At the back of my reading there is the claim of an endeavour to enforce the meaning in my own conduct for an unbroken period of 40 years. For this reason I do indeed harbour the wish that all Gujarati men or women wishing to shape their conduct according to their faith should digest and derive strength from the translations here presented.’ The path of the Gita, Gandhi said, was neither contemplation nor devotion; the ideal was sthitaprajna. Gandhi adopted, and wanted the Ashram community to adopt, a mode of conduct, a self-practice to attain a state where one acts and yet does not act. This mode, this disposition was yajna, sacrifice. Gandhi found the word yajna full of beauty and power. He saw this ideal of sacrifice as the basis of all religions. Gandhi emphasised the aspect of cultivating the disposition of a yogi, and his exemplar was Jesus Christ. It was he who had shown the path. Gandhi said that the term yajna had to be understood in the way ‘Jesus put on a crown of thorns to win salvation for his people, allowed his hands and feet to be nailed and suffered agonies before he gave up the ghost’.

For Gandhi, an act of service was sacrifice, or yajna. But how does one perform sacrifice in daily life? His response was twofold; for one, he turned to the Bible and other was uniquely his own. ‘Earn thy bread by the sweat of thy brow’, says the Bible. Gandhi made this central to the life of the Ashram and borrowed the term ‘bread labour’ from Tolstoy to describe the nature of work. It was dharma, duty, to perform bread labour, and those who did not perform this yajna, ate, according to the Gita, ‘stolen’ food. The other form of yajna was known as Yug-dharma, duty entailed upon one by the particular age. For Gandhi, the yajna of his times was spinning, his Yug-dharma. Spinning was an obligatory Ashram observance; each member was required to spin 140 threads daily, each thread measuring four feet. This spinning was called sutra-yajna, sacrificial spinning.

During the same year, students of the Gujarat Vidyapith that he had founded in 1920, and whose chancellor he was, invited him to give lectures. They wanted him to reflect on the life of Christ. The lectures on the Bible, specifically the Sermon on the Mount, began on July 24, 1926. The plan was to conduct these classes on each Saturday thereafter. But as soon as Gandhi began teaching the New Testament, he was ‘taken to task’ for reading it to the students. One correspondent asked, ‘Will you please say why you are reading the Bible to the students of the Gujarat National College? Is there nothing useful in our literature? Is the Gita less to you than the Bible? You are never tired of saying that you are a staunch Sanatani. Have you not now been found as a Christian in secret? You may say that a man does not become a Christian by reading the Bible. But is not reading the Bible to the boys a way of converting them to Christianity? Can the boys remain uninfluenced by the Bible reading?’ Gandhi saw this hypersensitivity as an indication of the intensity of ‘the wave of intoleration that is sweeping through this unhappy land’ and refused the correspondent’s request to give preference to the Vedas over the Bible. To him, his study and reverence for the Bible and other scriptures was wholly consistent with his claim to be a Hindu. ‘He is no Sanatani Hindu who is narrow, bigoted and considers evil to be good if it has the sanction of antiquity and is to be found supported in any Sanskrit book.’ The charge of being a Christian in secret was not new. He found it both a libel and a compliment. It was a libel because there were still people in the world, especially at a time when he was writing and publishing the Autobiography, who believed that he was capable of being anything in secret, for the fear of being that openly. He declared, ‘There is nothing in the world that would keep me from professing Christianity or any other faith the moment I felt the truth of and the need for it.’ This was a compliment, because therein Gandhi felt an acknowledgement, however reluctant, of his capacity for appreciating the beauties of Christianity. He wished to own up to that charge and the compliment.

Edited excerpts from Tridip Suhrud’s introduction to Mahatma Gandhi’s ‘An Autobiography or the Story of My Experiments with Truth’ (Critical Edition) courtesy Penguin Random House India

Gandhi’s all-embracing Hinduism

At the end of The Satyagraha Ashram Gandhi writes, “Politics, divorced of religion, has absolutely no meaning.” Time and again he asserted his identity primarily as a Hindu. However, he had a pluralist conception of religion. Religion for him was a matter of spirituality and social responsibility rather than institutional observance and dogmatic behaviour. In 1927 he wrote in Young India that “in spite of my being a staunch Hindu, I find room in my faith for Christian and Islamic and Zoroastrian teaching, and, therefore, my Hinduism seems to some to be a conglomeration … It is a faith based on the broadest possible toleration.”

He defined Hinduism as a search after truth through nonviolent means. His faith in Hinduism did not hinder him from condemning several Hindu customs and practices such as untouchability, child marriage and prohibition of widow remarriage. In his formative years Gandhi read widely and took inspiration from diverse sources. It is quite well known that the Gita and the Bible influenced Gandhi profoundly, but he also learned from western writers like Ruskin, Tolstoy and Thoreau.

Gandhi was influenced by British writer John Ruskin’s critique of distancing morality and ethics from economics and politics in his book Unto This Last (1862). He later translated the book into Gujarati as ‘Sarvodaya’ (well-being of all) in 1908. Russian writer Leo Tolstoy’s advocacy of non-violence in his theory of ‘non-resistance to evil’ also left a lasting impression on Gandhi. He also learnt from Tolstoy the ‘law of bread labour’, that is everyone must do physical labour.

Tolstoy used to work on his farm for eight hours a day in spite of being a nobleman, a practice Gandhi imbibed from him and practiced throughout his life. He put their ideas into practice by establishing the Phoenix Ashram (1904) in South Africa where all the residents were to get the same remuneration and lived as an integrated community, irrespective of their race, religion and nationality.

Although religion was very important to Gandhi, he believed it to be a personal matter. As a law student in England, Gandhi read the Bible and the life of Jesus inspired him immensely. MN Srinivas, in his article ‘Gandhi’s Religion’, notes that the notion of returning love for hatred and good for evil enthralled him. The suffering of Jesus for others had the greatest impact on Gandhi and he later incorporated this self-sacrifice (tapasya) in his philosophy of non-violence.

Gandhi also appreciated the Quran for its evolutionary view of religion and included verses from the book in his prayer meetings. In his book Communal Unity he stated his appreciation for Prophet Muhammad’s fasting and austere living. He also found justification of nonviolence in the Quran. According to him, although the Quran allows violence, it prescribes nonviolence as a duty. He believed in the unity of all religions. He not only helped in the establishment of Jamia Millia Islamia university for the education of Muslims but also sent one of his sons to study there.

He had a very different interpretation of the Bhagavad Gita than most others. According to him, it evinced the futility of violence and material desires. The ideal of acting without any desire for result (‘nishkama karma’) influenced him profoundly and led him towards a life of philanthropy. Gandhi focussed primarily on the ethical instead of the metaphysical aspect of religion. According to him, “every formula of every religion has in this age of reason to submit to the acid test of reason and universal justice if it is to ask for universal assent” (Young India, 1925).

Gandhi’s ideas are more than relevant in today’s time. In a society still struggling with communal tension and caste based violence, we need to hark back to his ideas of ahimsa and satyagraha. On the issue of cow protection which has resurfaced as a severe communal issue, he had written in Young India in 1921 that to “attempt cow protection by violence is to reduce Hinduism to Satanism.” As we enter the 150th year of the Gandhian era, let us not just remember the father of our nation but also the values that made him a ‘mahatma’ (great soul).

The writer is assistant professor of English at Deen Dayal Upadhyaya College

Isha Upanishad’s ‘Renounce and enjoy!’

When Gandhiji was asked if he could put the secret of his life into three words, he quoted from the Isha Upanishad: ‘Tena tyaktena bhunjithah’ – ‘Renounce and enjoy!’ But does this not seem contradictory? How can we enjoy something if we renounce it?

The Isha Upanishad is universally acclaimed for the precision with which it conveys the essence of Vedic philosophy. Therefore, in order to fully appreciate the importance of these three words quoted by Gandhiji, we need to understand the full meaning of the shloka referred to by him.

The first shloka of Isha Upanishad reads as follows: ‘Ishavasyamidam sarvam, yatkinca jagatyam jagat; Tena tyaktena bhunjitah, ma grdha kasya svid dhanam’.

Swami Ranganathananda, of the Ramakrishna Mission, translates this shloka as follows: ‘Whatever there is changeful in this ephemeral world, all that must be enveloped by the Lord. By this renunciation, support yourself. Do not covet the wealth of anyone.’ The same idea has been expressed somewhat differently by Swami Prabhavananda: “In the heart of all things, of whatever there is in :. . the Universe, dwells the Lord. He . alone is reality. Wherefore, reno- R N , C uncing vain appearances, rejoice in him. Covet no man’s wealth.”

It will appear that the shloka has three distinct, though interconnected, parts. Firstly, whatsoever moves on earth or whatever exists or is changeful in this ephemeral world, should be covered or enveloped by the Lord. Elaborating on this, Swami Parmananda says: “We cover all things with the Lord by perceiving the Divine Presence everywhere. When consciousness is firmly fixed in God, the conception of diversity naturally drops away; because the One Cosmic Existence shines through all things.”

The second part of the verse brings us to the crucial three words which Gandhiji has interpreted as ‘renounce and enjoy’. As explained above, ‘tena tyaktena’ means ‘through renunciation or detachment’ and ‘bhunjithah’ means ‘protect or support yourself’. Adi Shankra also interprets it as ‘protect’ because knowledge of our true Self is the greatest protection and sustainer. Although Gandhiji uses the word ‘enjoy’, it is intended to mean that having renounced the ‘unreal’, we may enjoy the ‘real’.

As Swami Ranganathananda explains, “In the language of Vedanta there must be both negation and affirmation. Therefore, if we are to enjoy this world, we must protect ourselves by renouncing whatever is not real.”

The shloka ends with a forthright directive: ‘Do not covet the wealth of another.’ This is a very plain statement but it involves a number of ethical and spiritual values. Whatever you have gained by your honest labour, that alone belongs to you; enjoy life with that and do not covet what belongs to others.

The whole purport of the first shloka of the Isha Upanishad, has been summed up as follows: Renunciation is an eternal maxim in ethics as well as in spirituality. There is no true enjoyment except what is purified by renunciation. This world is worth enjoying and we should enjoy it with zest.

Zest for life is expounded throughout the Bhagwad Gita and the Upanishads. Great teachers who discovered these truths were not killjoys; they were sweet and lovable people. Sri Ramakrishna was full of joy and Sri Krishna too was full of joy. But before we can enjoy this world, we have to learn the technique of enjoyment and this technique is: ‘Renunciation’.

Ram Rajya

Madan Mohan Mathur, MK Gandhi’s Vision Of Ram Rajya, March 13, 2019: The Times of India

Whether we consider the Ramayana as history or mythology, it cannot be denied that the concept of Ram Rajya is an integral part of our cultural inheritance. Establishment of Ram Rajya has been the ultimate ideal of genuine political leaders, right from those who engaged in India’s freedom struggle led by Gandhiji, to those in successive elected governments, post-Independence.

Writing in ‘Young India’ (September 19, 1929), Gandhiji had said: “By Ram Rajya I do not mean Hindu Raj. I mean Ram Raj, the kingdom of God. For me, Ram and Rahim are one and the same; I acknowledge no other God than the one God of Truth and righteousness. Whether Ram of my imagination ever lived on this earth, the ancient ideal of the Ramayana is undoubtedly one of true democracy in which the meanest citizen could be sure of swift justice without an elaborate and costly procedure.” In the Amrit Bazar Patrika of August 2, 1934, he said: “Ramayana of my dreams ensures equal rights to both prince and pauper.”

Again, in the Harijan of January 2, 1937, he wrote, “By political independence, I do not mean our imitation of the British House of Commons, the Soviet rule of Russia, the Fascist rule of Italy or the Nazi rule of Germany…We must have ours, suited to ours … I have described it as Ram Rajya, that is, sovereignty of the people based on moral authority.” According to him, the ideal Ram Rajya may be politically described as “the land of dharma and a realm of peace, harmony and happiness for young and old, high and low, all creatures and the earth itself, in recognition of a shared universal consciousness.”

However, writing in the Harijan on June 1, 1947, just two months before Independence, Gandhiji lamented that “there can be no Ram Rajya in the present state of iniquitous inequalities in which a few roll in riches and the masses do not get even enough to eat!” Apparently, after the initial euphoria of Independence and the unexpected violence resulting from the Partition, the focus of political leaders shifted towards building India into a secular and socialistic society, taking a leaf from the ideology of Soviet Russia. Over the following decades, overzealous secular politicians tried to reduce Ram Rajya to a metaphor; while its spiritual and religious connotation were overlooked.

After the demolition of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya in 1992, and the later change in political ideology of the netas in power, the emphasis suddenly shifted to the rebuilding of a Ram Mandir in Ayodhya. Ambitious and elaborate plans have been announced over the years, while a dispute over possession of the land is pending in the courts. In February 2018, a 41-day yatra was flagged off from the Vishva Hindu Parishad in Ayodhya, with the main agenda being to administer a pledge to the people for construction of the Ram temple and re-establishment of Ram Rajya in the country.

Now, after 71 years of Gandhiji’s martyrdom, the political atmosphere is again reverberating with demands for construction of a Ram temple in Ayodhya, converting it into a big political and legal issue, especially in the context of the coming general election. While construction of a Ram Temple in Ayodhya is a legitimate aspiration, the real question we need to ask ourselves is, whether mere construction of a temple or a murti of Rama will establish Ram Rajya as dreamt of by Gandhiji.

Philosophy, views

From: Oct 2, 2019: The Times of India

Champaran Satyagraha

Indeed, Champaran Satyagrahas marked the emergence of Mahatma from M. K. Gandhi wherefrom began a new era in India’s freedom struggle.During those days when popular protests were repressed by brute force unleashed by the British Government, the strategy of peace and non-violent persuasion in Champaran proved to be highly useful as it discouraged the English rulers from resorting to barbarity against the agitators.

With Mahatma Gandhi’s approaching martyr day very close to observe, everyone is reminded of his immense contribution towards selfless service of humanity suffering the agony and trauma of utter ignorance, poverty and wretchedness and also violence, injustice or inequality of all kinds all over the world.And that moved Gandhi’s inner core which motivated his pious self to jump into fulfilling his lifelong mission for alleviation and uplift of these millions as he could feel the inner voice of their hearts. While he was working in South Africa towards this end but his deep passion for service of own motherland brought him back to India where he began with this utter desire to serve the hapless millions.And the farmer’s agitation in Champaran against various forms of prevailing injustice provided him the required opportunity to practice his noble ideas into action wherein he proved to be very successful. In fact, the Champaran peasant movement was a part of the wider struggle prefixed for independence. When Gandhiji returned from South Africa, he wanted to experiment with his first-ever non-cooperation satyagraha,as alimited endeavour, by providing leadership to the infant peasant agitations at Champaran in Bihar and later atKheda in Gujarat. Although these struggles were taken up as reformist movements yet the underlying rationale was to mobilise the peasants towards their genuine demands meant for their survival.Indeed,Champaran Satyagraha was based on insistence on ‘truth and non-violence’,along-with persuasive strategy. It was organized as a peaceful movement in total contradiction with the violent peasant uprisings in the past. Fortunately the movement received massive support from some of the prominent leaders of the country like Rajendra Prasad, Brijkishore Prasad and Muzhar-ul-Haq who constituted the progressive intelligentsia of the then India. This provided strength and a constructive direction to the movement. Can’t it become again a role model in today’s world fraught with never-ending macabre violence and global terrorism?

In the early 19th century, European planters had set up indigo farms and factories at Champaran, in North Bihar. Thereafter, they forced the local cultivators to enter into the tinkathia system, which stipulated that out of 20 khatas which make an acre, they had to dedicate 3 khata sexclusively for indigo plantation. Though the peasants (bhumihars) of Champaran and other adjoining areas of Bihar were growing the Indigo under the tinkathia system, they had to lease this part in return to the advance at the beginning of each farming season and adding further to their woes, they were compelled to sell their crops at a throw away price which was fixed on the area cultivated by them rather than the crop produced. When the demand for indigo in the international market began to fall with the arrival of German synthetic dyes, the European planters passed the burden of losses over these cultivators, besides raising rents and extracting other illegal dues from them lest they close producing indigo. As Indigo plantation had been destroying the fertility of their soil they had nothing but to protest against such unjust farming. Consequently, the planters used illegal and inhuman methods of indigo cultivation upon the poor peasants while forcefully subjecting them to an extremely inadequate remuneration. Further these planters demanded heavy price from the peasants in lieu of relieving them from the lease contracts. Thus, as a whole, they were being bitterly cheated by the planters and the overall situation had become very horrible as well as pathetic which compelled a noted writer and documentary-maker D.G. Tendulkar to write: ‘The tale of woes of Indian ryots, forced to plant indigo by the British planters, forms one of the blackest in the annals of colonial exploitation. Not a chest of Indigo reached England without being stained with human blood.’

Against this backdrop, an enlightened peasant in Champaran, Raj Kumar Shukla who was also suffering this highhandedness, managed to persuade Gandhiji to survey the area to standup for the cause of the exploited peasants. Hence Gandhiji and his supporters visited extensively through villages,while listening to their grievances, and recording their horror tales of repression. Thus Gandhiji could understand the inhuman misery and brutal savagery which these peasants had been suffering from in the Champaran.Hence their miseries were discussed thread-bar at the annual conference of the Bihar Provincial Congress Committee on 10th April, 1914,which concluded that the Champaran peasants were really suffering their worst. And that again motivated the Provincial Congress Committee in 1915 to recommend for constitution of an inquiry committee to assess the woes of the Champaran peasantry. As the issue had drawn countrywide attention by then, the Indian National Congress, in its Lucknow session in 1916, also discussed the Champaran case to decide for immediate remedial measures for them.

Hence, Gandhiji chose to represent the peasants’ cause and initiated the Champaran peasant movement which was launched in 1917-18. Its objective was to create awakening among the peasants against the prevailing exploitation of the European planters. On 14th May, 1917 Gandhiji wrote a letter to the District Magistrate of Champaran, W.B. Heycock, wherein he showed his deep concerns about the sufferings of peasants at the hands of landlords and also the Government of the day. The peasants opposed not only the planters but also zamindars,as they were equally brute and oppressive for the peasants though Gandhiji wanted to normalize their mutual relations. Meanwhile, a Champaran Agrarian Committee had already been constituted by the Government, with Gandhiji as one of its members. As pressure mounted against such exploitation and the recorded statements of about 8,000 peasantstestified the inhuman exploitation and barbarity, the Government had to accept Gandhiji’s suggestion of abolishing the tinkathia system. The European planters had to sign an agreement granting more compensation and control over farming to these poor farmers and cancellation of revenue hikes and collection until the famine ended. Furthermore, the planters were asked to refund 25 percent of the amount they had illegally collected from the peasants as enhancement of dues.

Thus the Champaran Satyagraha became a grand success and turned to be a powerful tool of civil resistance in the ensuing India’s freedom struggle. The psychological impact of this Satyagraha was outstanding as it aroused firm belief in truth and non-violence among the suffering peasants of Champaran and also among the countrymen as well. Indeed, the satyagrah aproved to be a great morale booster to not only Gandhiji -which made him a global symbol forever – and the Champaran peasantry but became an icon of peaceful and non-violent struggle for the whole nation and also the whole world. In fact, this icon is the only option even today for survival of innocent humanity bearing the brunt of ever-recurring gruesome violence and various forms of terror, besides innumerable temporalpains and physical difficulties in every nook and corner of the world.

(The author is Political Science, U.P. Rajarshi Tandon Open University)

Racism against the Africans?

Anger Against Mahatma's Use Of Slur For Africans In Writings

Three months after President Pranab Mukherjee gifted a statue of Mahatma Gandhi to the University of Ghana, a group of professors and students have started a petition to bring it down.

The opposition centres around their belief that Gandhi was “inherently racist“ for his depiction of native black Africans as “kaffir“ (considered a racial slur in Africa) in his early writings, when he was fighting for the rights of Indians in South Africa.

According to reports, some members of the university , led by a former director of the Institute of African Studies, Professor Akosua Adomako Ampofo, have started a campaign to get the institution to pull down the statue, which was unveiled during a visit by President Pranab Mukheriee in June. natures, which comes as an embarrassment to the Indian government.

The campaign carries the slogan `Gandhi Must Fall' and `Gandhi For Come Down' (pidgin for Gandhi Must Come Down), inspired by the “Rhodes Must Fall“ campaign against a statue of Cecil Rhodes at Oxford University .

The statue was installed at the recreational quadrangle of the university's Legon campus in Accra.

Apart from a campus agitation, a petition to the university authorities on change.org has already attracted 872 signatures in a bit of a quandary . The site was chosen by the Ghana foreign office when the President went for a visit in June. While there are some voices preaching moderation, the ministry of external affairs is also waiting to see whether the campaign gathers steam.

The offensive passages

One of Gandhi's writings that have been cited in the petition reads thus: “A general belief seems to prevail in the Colony that the Indians are little better, if at all, than savages or the Natives of Africa. Even the children are taught to believe in that manner, with the result that the Indian is being dragged down to the position of a raw Kaffir.“ (Dec 19, 1894) A second, more damaging (Sept. 26, 1896) one reads: “Ours is one continual struggle against a degradation sought to be inflicted upon us by the Europeans, who desire to degrade us to the level of the raw Kaffir whose occupation is hunting, and whose sole ambition is to collect a certain number of cattle to buy a wife with and, then, pass his life in indolence and nakedness.“ (The petitioners have sourced the quotes from Gandhi and South African Blacks http:www.gandhiserve.orgecwmgcwmg.htm ) Putting an international spin to their petition, they listed a number of colleges and universities around the world seeking to remove the overt symbols of racism.

Religion

Organised religion vs. ethical/ moral practices

Ashok Vohra, Recalling Gandhiji's Perspective On Religion, October 2, 2017: The Times of India

MK Gandhi was aware of the difficulties in defining the term `religion'. He took pains to explain it in a number of his writings over several years. He was aware that the term religion can be, and is, used in two senses to refer to organised religion and to refer to ethical or moral practices that have their root in a specific ontology and metaphysics.

He uses the term in both these senses. In `Hind Swaraj' he says, “Religion is dear to me ... Here i am not thinking of the Hindu ... or the Zoroastrian religion, but of that religion which underlies all religions.“ That Gandhi does not use the term religion to connote such individual religions or faiths is clear when he says, “By religion, I do not mean formal religion, or customary religion, but that religion which underlies all religions, which brings us face to face with our Maker.“

Elaborating on his use of the term `religion' further, he says, “Religion does not mean sectarianism. It means a belief in ordered moral government of the universe.“ According to him, religion is that “which transcends“ the limits of any particular religion. It does not supersede individual religions like Hinduism, Islam, Christianity ... but “harmonises them and gives them reality“.

This kind of religion is one “which changes one's very nature, which binds one nature, which binds one indissolubly to the truth within, and which ever purifies. It is a permanent element in human nature which counts no cost too great in order to find full expression and which leaves the soul utterly restless until it has found itself, known its Maker and appreciated the true correspondence between the Maker and itself.“

Gandhi in `Hindu Dharma' explains this: “All of us with one voice call God differently as Parmatma, Ishwara, Shiva, Vishnu, Rama, Allah, Khuda, Dada Hormuzada, Jehova, God, and an infinite variety of names. He is the One and yet many; He is smallest, smaller than an atom, and bigger than the Himalayas. He is contained even in a drop of the ocean, and yet not even the seven seas can encompass Him.“

That Gandhi does not regard religion or being religious or following of a religious order or creed as something external, some kind of a `job' or `profession' is abundantly clear when he asserts, “I do not conceive religion as one of the many activities of mankind.“ The main reason for this is that “the same activity may be governed by the spirit, either of religion or of irreligion.“

Gandhi regards being religious as something inherent to humankind. The term religion, as used by him pervades all our activities. Therefore, he concludes, “For me every , tiniest activity is governed by what i consider to be my religion.“ He explicitly admits this fact when he says, “This is the maxim of life which i have accepted, namely , that no work done by any man, no matter how great he is, will really prosper unless he has a religious backing.“

Gandhi's notion of religion is `metaphysical or the ideal'. In this context, there can be no conflict between religions because it assumes that there is just one universal religion or that there is just one religion underlying all religions. Then, the word religion would be always used in singular and never in the plural.

Satyagraha and The Three Monkeys

The Times of India, Oct 02 2015

K M Gupta

One way of fighting evil is not to shut it out from our senses

Granted, there is so much evil in the world corruption, nepotism, terrorism, for instance. But it is beyond us to change what is widespread. We have seen even well-intentioned people entering politics to cleanse it and then getting sucked into its vortex. It is a misconception that the world was good in the past, and it has worsened only now. The world was always the same and will be always so, perhaps.

So, do we accept evil, surrender to it?