Mahili

This section has been extracted from THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all posts in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

Contents |

Mahili

Origin and internal structure

Mahali, a Dravidian caste of labourers, palanquin¬bearers, and workers in bamboo found in Chota Nagpur and Western Bengal. They are divided into five sub-castes-Bansphor¬Mahili, who make baskets and do all kinds of bamboo work; Patar¬Mahili, basket-makers and cultivators; Sulunkhi-Mahili, who are cultivators and labourers; Tanti-Mahili , who carry palanquins; and Mahili-Munda, a small outlying sub-caste confined to Lohardaga. A comparison of the totemistic sections of the Mahilis shown in Appendix I with those of the Santals seems to warrant the conjecture that the main body of the caste, that is to say the group comprising the :Bansphor, Sulunkhi, and Tanti Mahilis, is merely a branch of the Santals, separated at a comparatively recent date from the parent tribe. The exact causes of the separation are, of course, lost in the obscurity which enshrouds the early history of all tribal movements. But the fact that the Mahilis make baskets and carry palanquins; occupations which every Santal would deem degrading, suggests that the adoption of these pursuits may have given the first impulse to the formation of the new group. The Mahili-Munda possibly parted from the Munda tribe for similar reasons. Besides the sections shown in the Appendix the entire sub-caste regard the pig' as their totem, and consider it wrong to eat pork. It is rumoured, indeed, that appetite often gets the better of tradition, but that in such cases the carcase alone is eaten, and the consequences of breaking the taboo averted by throwing away the head. The Patar-Mahili are a Hinduised sub-caste of South-East Manbhum, who employ Brahmans as priests and abstain from eating beef.

A man may not marry a woman of his own section 01' of the section to which his mother belonged before her marriage. Beyond these limits marriage is regulated with reference to the standard formula for prohibited degrees.

Marriage

Mahilis marry their daughters both as infants and as adults, but the former practice is deemed the more respectable, and there can, I think, be little doubt that in this, as in other castes on the borders of Hinduism, the tendency at the present day is towards the entire abolition of adult-marriage. The customary bride-price paid for a Mahili girl is supposed to be Rs. 5, but the amount is liable to vary according to the means of the bridegroom's parents. On tbe wedding morning, before the usual procesion starts to escort the bridegroom to the bride's house, he is formally married to a mango tree, while the bride goes through the same ceremony with a mahmi. At the entrance to the bride's house the bridegroom, riding on the shoulders of some male relation and bearing on his head a vessel of water, is received by the bride's brother, equipped ill similar fashion, and the two cavaliers sprinkle one another with water. The bride and bridegroom are then seated side by side on a plank under a canopy of sal leaves erected in the courtyard of the house, and the bride¬ groom touches the bride's forehead five times with vermilion, and presents her with an iron armlet. This is the binding portion of the ritual. So far as positive rules are concerned, the Mahilis appear to impose no limit on the number of wives a man may have. It is unusual to find a man with more than two; and practically, I understand, polygamy is rarely resorted to unless the first wife should happen to be barren. Widows may remarry, and are under no restrictions in their choice of a second husband, though it i deemed right and proper for a widow to marry her deceased husband’s younger brother if such a relative exists, Divorce is permitted on the ground of adultery or inability to agree. When a husband divorces his wife he gives her a rupee and takes away the iron armlet (lohar ,. kharu) which was given her at her wedding. He must also entertain his caste brethren at a feast by way of obtaining their sanction to the proceedings. Divorced wives may marry again. Like the Bauris and Bagdis, the Mahilis admit into their caste men of any caste ranking higher than their own. The conditions of membership are simple. The person seeking admission into the Mahili community has merely to pay a small sum to the headman (pa1'ganait) of the caste and to give a feast to the Mahilis of the neighbourhood. This feast he must attend himself, and signify his entrance into the brotherhood by tasting a portion of the food left by each of the guests on the leaf which on these occasions serves as a plate.

Inheritance

In matters of inheritance and succession the Mahilis profess to follow whatever law applies to the Hindus of the locality-•the Dayabhaga in Manbhum and the Mitakshara. in Lohardaga. Statements of this kind, however, import little more than a vague assumption of conformity with what is supposed to be the custom of all respectable men; and there is no reason to believe that the headman (pargandit) and caste¬ council (panchayat) who settle the civil disputes of the caste, haye any knowledge of, or pay the smallest regard to, the rules of the regular Hindu law. The questions which come before this primitive tribunal are usually very simple. Its decisions are accepted without question, and I know of no instance where an attempt has been made to conect them by appealing to the regular courts. It does not follow, however, that Mahilis and castes of similar standing have escaped the influence of the Codes and have preserved a distinct customary law of their own. On the contrary, the written law certainly filters down to these lower grades of society, not through the regular channels of text-books and courts, but in virtue of their tendency to imitate the usages of the groups immediately above themselves. If men of these lower castes are asked what law they follow, a common answer is that they have the same law as their landlords; and the landlords, to whatever caste they may belong, almost invariably get their law from the text-books and the courts. To this influence it is probably due that the practice of giving an extra share (Jeth-angs) to the eldest son in dividing an inheritance is gradually dying out among the Mahilis, and the tendency is towards an equal division of property.

Religion

The religion of the Mahilis is at present a mixture of half-forgotten animism and Hinduism imperfectly understood. They affect indeed to worship all the Hindu gods, but they have not yet risen to the distinction of employing Brahmans, and their working deities seem to be Bar¬pahari and Manasa. The former is merely another name for the well-known mountain god of the Mundas and Santals, while the latter is the snake goddess, probably also of non-Aryan origin, whose cult has been described in the article on the Bagdis. To these are offered goats, fowls, rice, and ghi, the offerings being afterwards eaten by the worshippers themselves.

Disposal of the dead

The Mahilis of Northern Manbhum bury their dead face down¬wards; but this practice is not univers for the Patar Mahilis and the Mahilis of the Santal Parganas burn their dead and bury the ashes near at hand. On the eleventh day after death offerings of milk, ghi, and rice are made at the place of burial. Similar offerings are presented in the months of Kartik and Chait for the propitiation of departed ancestors in general. The anniversary of the death of an individual ancestor is not observed.

Social status and occupation

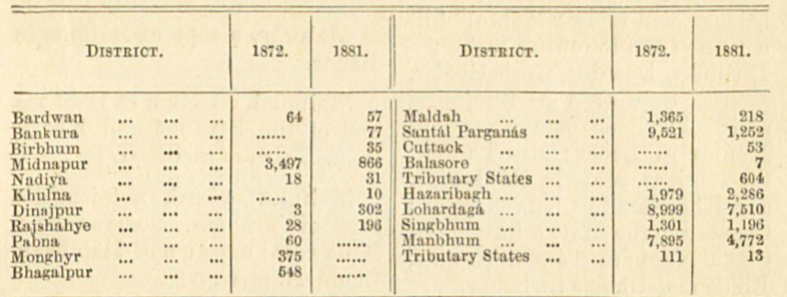

Mahilis rank socially with Bauris and Dosadhs. They eat beef, . pork, and fowls, and are very partial to strong drink. Field-rats, which are reckoned a Epeciat delicacy by the Oraons, they will not touch. They will eat cooked food with the Kurmi, the Bhumij, and the Deswali Sanbils. They believe their original occupation to be basket-making and bamboo work generally. Many of them are DOW engaged in agriculture as non- oocupancy raiyats and landless day-labourers. The following statement shows the number and distribution of Mahilis in 1872 and 1881 :¬