Makli

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Makli

Makli the mystique lives on

By Masume Hidayatullah and Haris Gazdar

Makli is hauntingly, eerily beautiful, which can be easily categorised as a must-see destination. Go at sunset when the intricately carved sandstone is bathed in a glowing orange light. Go at night (the site is open 24/7), armed with a candle-lit picnic and dine with the ghosts and spirits of powerful suzerains and emperors who constructed these eloquent monuments to celebrate their own, and their families’ lives and deaths. Go during the day to peer and then step inside these imposing hollow structures, often open to the heavens, and experience their cool sanctuary and rose-strewn sarcophagi, only to wonder; is a long lost descendant of these once mighty rulers a regular visitor to their stately remains?

The makam, or necropolis or even cemetery, of Makli rises above the dried up river bed of what used to be the path of the mighty River Indus. Makli is situated a few kilometres outside Thatta, once a city of great strategic importance that prospered until the Indus changed its course away towards the east.

It is generally believed that the necropolis grew around the tomb of a 14th century Sufi saint, Hamad Jamali. It now covers a wide area (of circa 15 square kilometres) and appears at first glance to be a series of dusty mounds and hillocks. But persevere. Enter through the main gates (in your car – no hidebound bureaucracy here, this is tourism as it used to be in the golden age of the motor car, that grand old decade of the 1970s). Follow the advice of those in the know and ask your driver to take you straight down the rough track to the very end of the site. Keep the windows rolled up and the air conditioner on as you drive through the site – for it is only when you reach the very end of the track that you will be ready for the sensory overload you are about to experience.

The vehicle will jolt along the track, well-marked by limestone painted rocks of different sizes to guide night-time drivers through the site. On either site of the track, the land rises and falls; the visitor is never quite certain of where the stones end and the low level (broken) graves begin. Larger structures rise up in ad-hoc fashion, some intact, some fallen victim to an unrecorded combination of weather and vandalism.

Emerging at the end of the track from the air-conditioned vehicle, the visitor is engulfed by a slightly saline breeze (in itself a mystery as not only has the river dried up, but this site is about 80 kilometres from the tip of the Indus delta), infusing all with a magical and unearthly calmness. An acoustic engineer would be hard pressed to create the deafening silence that pervades this mystical place. The breeze seems to dampen sound, each footstep sounds like a delicate thud, the sandstone crevices of the monuments soaking up manmade sounds of human, bird and insect chatter. Or perhaps it is the wind that carries the sounds away to ensure that the sleeping residents are not disturbed.

And all the while, a magical orange sunset embraces the sandstone monuments and pavilions – the very monuments that make up this unusual, haunting site. What appears at first glance to be randomly set structures are in reality the tombs and monuments, landscaped and spaced almost to perfection. No one tomb or funerary monument obscures the view or solar aspect of any other. The breeze, the dumbfounding silence, the intricately carved sandstone: all these elements combine to please the senses. This is a place to think and clear the mind of the detritus that usually clouds it. Take some time out and savour the experience.

This end of the site is the furthest away from the entrance and is the chronological start of the tour. The oldest surviving monuments are here, dating from the early to middle part of the 15th century. The land dips down here and leads to the final resting place of a local saint which is open year round and at all hours to the visiting public and is of course subject to strict dress codes for men and women.

Time permitting it is a worthwhile addition to the Makli experience; requesting the moral, physical or even financial assistance of a deceased holy man is a time honoured tradition in Sindh (usually done in exchange for a supplication to request the saint’s soul to continue to rest in peace) and the donation of alms to the less fortunate who are praying at the tomb. However this detour should only be made once the Makli tour is complete.

The best preserved funerary monument at this site is the tomb of the former ruling Samma family dating from the 1450s, specifically, the tomb of Jam Nizamuddin, reigned 1461–1509. A fascinating profusion of styles, combining early Islamic, Gujarati and Rajasthani material and methods of construction, it is closely guarded by a handful of sandstone pavilions elegantly placed at a close but respectful distance. The monument is kept locked, but again, persevere. A watchman appears, as if from nowhere, armed with knowledge, facts and keys to allow entry to the sanctuary. The monument contains both adult and child sarcophagi, simply set against the intricate carving on the internal walls of the tomb. Despite having no roof, the interior is immaculately clean and well-respected. The quality of the interior belies its age, due to the most judicious choice of suitable building materials to cope with local climactic conditions.

Spend as much time as is needed to soak in the atmosphere around this monument. Walk around to its rear and at a lower level, track the path of the river that once flowed here. Admire the Hindu style pavilions in the immediate vicinity and the graves of Jam Tamachi and his child from Noori, together the subjects of the Noori-Tamachi legend.

This part of the site is at least two to three kilometres away from the main entrance. Personal energy levels and weather permitting, walk the entire length of the site back towards the main entrance, keeping an eye out for the chronological evolution of the architectural styles slowly shifting away from a Rajasthani influence to that of Herat, Isphahan, Bokhara and Samarkand in the 15th and 16th centuries, yet at the same time retaining a frisson of the exotica of India — a carved lintel here, an animal relief there.

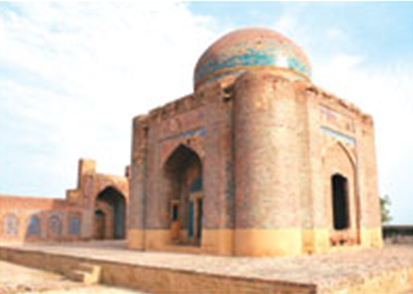

The most impressive and best preserved monument at this end of the site is the Turkhan family’s tomb. The name itself merits further research. Who and what was this dynasty. How did they find their way, perhaps from the Turkmen heartlands, perhaps from Badakshan or Qandahar, to the plains and deserts of Sindh, and for what motive? Did they come as warriors or traders? So many questions, such little time. Makli is a place that will get the visitor searching for historical facts to balance out the mysticism that it imbibes.

As with the Samma era monumnent, the Turkhan family tomb (the mausoleum of Isa Khan Tarkhan II died 1651) is kept under lock and key, but can be visited. This is a large space, a private multi-storeyed mansion — this time with a roof — set in a high walled compound which serves as the final resting place of a dynasty. Elegantly laid out, perhaps originally with its own green spaces and fountains, its welcoming proportions beckon in the visitor.

Makli is a Unesco World Heritage site, yet remains in danger of being forgotten by all, save the dedicated archaeologist with a specialised interest in Islamic funerary structures of Sindh. Makli’s presence, a mere three-hour drive from Karachi, requires celebration and nurturing. It requires public interest in Sindh’s fabulously wealthy heritage and its unique geo-strategic position that allowed the most original of cultures and relationships to flourish for many hundreds of years.

Makli: Pre-Islamic stupa collapses

Pre-Islamic stupa at Makli collapses

By M. Iqbal Khwaja

THATTA, Nov 10: A pre-Islamic period stupa collapsed here at Makli incline on Saturday due to alleged negligence of the archaeology department of Thatta.

The picturesque structure, a unique formation of yellow carved stones with various portraits of people, was mounted along the foundation ruins of a Shiv Mandir at the old Makli incline.

According to Prof Dr Mohammad Ali Manjhi, Secretary General of Thatta Historical and Cultural Society, the stupa had been named after a staunch religious community “Menkila or Mingla” and the name of Makli Hills was also a refined adoption of the name Menkila.

During the compilation of historic book “Makli Nama” by Pir Husamuddin Rashdi, G.M. Syed had suggested to the author in letter to include the facts about Menkila and the author preferably reported the letter in preface of the book.

During Talpur dynasty in Sindh the stupa was about to cave in, but the British rulers restored the beauty of this marvellous structure.

Sensing the mounting danger to the structure and frequent detachment of relic stones from the stupa by relic thieves, Dr Manjhi said, he had personally approached the curator of archaeology department and even offered contributions from well-to-do people to save the monument but the officials paid no heed, with the result that the historic stupa collapsed.

The people have lost a picturesque monument which was bound to disappear if no official turned up to restore it, he added.