Malana, Himachal Pradesh

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

History

A Greek connection?

Rohit Mullick, January 1, 2023: The Times of India

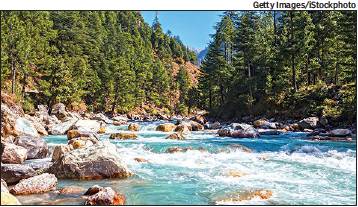

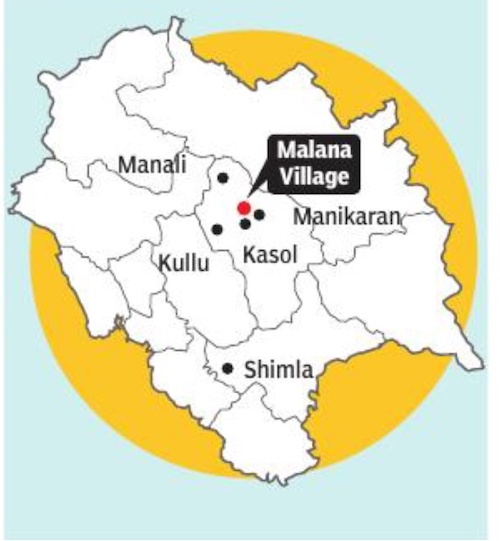

When Alexander turned back from the Beas in Punjab, in 326 BCE, legend says some of his soldiers continued eastward into the mountains and settled down at a place now known as Malana in Himachal Pradesh. Surrounded by vertical mountain walls, this village in Kullu district’s Parvati valley remained hidden from the outside world for centuries. Its unique language – Kanashi – culture and people’s distinctive features lent weight to the legend. But are Malana’s inhabitants really the descendants of Alexander’s army?

DNA To Solve Mystery

Although studies on Malana’s culture and language have been done over the past 70 years, it’s only now that its ‘Greek connection’ is being probed. Dr Anil Kumar Singh, an expert on Hellenic studies from Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), has teamed up with Greek scholars to unravel this mystery.

Singh, who teaches at the School of Language, Literature and Culture Studies, JNU, and heads the IndoHellenic Research Centre, says it can’t be said “beyond doubt that all the soldiers who were part of Alexander’s army went back home. Some must have stayed back”. He plans to make a multidisciplinary research team within the next six months that will use the latest scientific techniques. “I am hopeful that we will have a team of scholars from various fields, including genomics, by the time we have our next scheduled conference in Venice in September this year…. We are going to use DNA analysis to find out whether the legend is true or not. ”

This won’t be the first genetic study in Malana, though. In 2010, Indu Talwar and Rajiv Giroti’s research showed Malana is a ‘genetic isolate’ with little or no genetic mixing with other populations. But that was largely attributed to the village’s historic isolation and the practice of endogamy (marriage within the community).

History Is Silent

Malana has been a topic of serious research since at least the 1950s when Collin Rosser, an anthropologist, spent two years studying its language, culture and democratic system of governance. Rosser had termed Malana “a hermit village”, strongly united against all outsiders. In fact, outsiders are not welcome even today and are made to pay a fine if they touch any object considered sacred.

But over the years, no historical evidence linking Malana to Alexander’s Greek army has emerged. Dr Ory Amitay, a historian at the University of Haifa in Israel and author of ‘From Alexander to Jesus,’ a book that traces Alexander’s life as a mythological figure, says: “I have not seen anywhere even a hint of reliable evidence for an actual connection between Alexander and Malana in antiquity. The rebellion of the soldiers, which forced Alexander to turn back, did happen before crossing the Hyphasis river, now known as the Beas. But Greek and Latin sources do not say anything about anyone who crossed the river and settled there. ”

“There is no historical proof that remotely connects Malana villagers with Greek soldiers. This is just a legend,” agrees Lucknowbased historian and author Preeti Singh, who has written a research paper on Malana. Doesn’t Sound Like Greek.

Even the research on Kanashi shows it has no link with ancient Greek. Instead, it is a Sino-Tibetan language closely related to Kinnauri. One theory posits that Malana was founded by Kanashi-speaking people from Himachal’s Kinnaur district. Perhaps, traders from Kinnaur founded Malana, which lay on an ancient trade route connecting Bushahr in the Satluj valley with the Parvati valley. Recent research on Kanashi by professor Anju Saxena and Lars Borin from Uppsala University in Sweden also concludes that “Kinnauri-Kanashi speakers had moved to Kinnaur from the southern Uttarakhand region, and later on some of them migrated to the present-day Malana where Kanashi continued developing. ”

A Colonial Fantasy?

So how did Malana get intertwined with Alexander’s army? Dr Amitay, who had visited Malana in the mid-1990s, says, “The story about soldiers could have been invented by some Briton back in the days when the Crown had an empire and the classics were widely read, or even by someone from the flourishing northIndian tourist industry. ”

Dr Richard Axelby, an anthropologist who teaches at SOAS University of London and has written a paper on Malana, says the story would have been started by European explorers and settlers in the Western Himalayas.

“Europeans in India, the recipients of a classical education, knew that Alexander’s army turned back after reaching the Beas. Hearing about the village of Malana with its unique language, strange customs and system of democracy, 19th-century European travellers would have reached back to explain the isolated community as a remnant of Alexander’s army,” Axelby says, adding, “This connection would have been strengthened as archaeologists like Aurel Stein and JP Vogel uncovered evidence of Indo-Greek kingdoms in NW India. ”

‘Children Of Jamlu Devta’

Above all, the natives of Malana vehemently reject their Greek origin story. “We are not in any way connected to Greece or Alexander. We never made such a claim,” says Raju Ram, pradhan of Malana village who is in his early 50s. “We are the descendants of Jamlu Devta and we speak a language no one else does or understands. This is the truth about us. The rest is a lie. ” The villagers believe Jamlu came from Tibet to Spiti, entered Malana through the Chanderkhani Pass and founded the village. One of their legends says the gods of Kullu didn’t want Jamlu to settle there, so they kicked a bucket with Jamlu inside it. It soared over the mountains and landed in Malana.

ENDANGERED LANGUAGE

Kanashi is a Sino-Tibetan language spoken by the 2,200-odd inhabitants of Malana, whereas all the surrounding villages speak an Indo-Aryan dialect. It does not have a script so it is passed on orally. A recent study by Sweden’s Uppsala University shows a substantial portion of the Kanashi lexicon is borrowed from Indo-Aryan languages. Linguists have categorised Kanashi as a West-Himalayish language, closely related to Kinnauri, a language spoken by the people of Himachal’s Kinnaur district.

Seclusion

As in 2021

Suresh Sharma, May 17, 2021: The Times of India

From: Suresh Sharma, May 17, 2021: The Times of India

Malana village has succeeded in keeping the coronavirus out, so far. Secluded naturally, as it is perched on the far end of Parvati valley, the village is one of the largest in Himachal Pradesh’s Kullu district, with a population of about 2,350. However, it has always guarded its seclusion zealously and opened up to outsiders not too long ago. In these times of the Covid-19 pandemic, the villagers have once again fallen back into the old habit patterns and barred the entry of outsiders since March last year.

Paras Ram, a local, said: “When we heard of coronavirus last year, we were terrified and we started thinking about ways to protect ourselves. The first step we took was to ban the entry of outsiders. We guarded all the entry points to ensure not a single unknown person came in. We also stopped unnecessary movement outside the village. We do not wear masks or maintain physical distance inside the village. We know that if the disease enters Malana, it will wreak havoc.”

Malana has had its own judicial system and all works in the village are still done with the ‘advice’ of Jamlu Devta, the most revered God of the residents. It was only about three decades ago that some officials had succeeded in convincing the residents to follow the national Constitution. The village then became notorious for producing Malana Cream, the world’s most expensive charas. Then a large number of tourists started visiting the village, some to know its culture and others for charas. Today, its economy is dependent on both tourism and charas. A majority of the residents are still illiterate.

“We have kept all guesthouses, homestays and eateries closed since March last year. Tourists have not been allowed to enter Malana for over a year now. Those involved in tourism activities have been warned that they will be solely responsible if they allow in outsiders and bring disease to the village,” said Bhagi Ram, former panchayat president of Malana.

Last year, the village had announced a fine of Rs 51,000 for violation of rules framed by locals to protect themselves from Covid-19.

YEAR-WISE DEVELOPMENTS

As in 2024

Rohit Mullick, February 11, 2024: The Times of India

From: Rohit Mullick, February 11, 2024: The Times of India

From: Rohit Mullick, February 11, 2024: The Times of India

Dalip Ram is in his sunset years and he does not like the way his world is changing. New concrete buildings with green and red tin roofs, outsiders trooping into the village, village girls marrying outside. “We were all happier living in isolation, away from the outside world,” he says.

Isolation was his village Malana’s calling card once. AFP Harcourt, one of the first White men to visit the village in Kullu’s Parvati valley, in 1870, described Malanis as “strange people” who “hold themselves aloof from everyone”. Some called it a hermit’s village due to its geographical isolation and cultural and linguistic quirks: Kanashi, the language of Malana, has Sino-Tibetan roots and only 2,200 speakers. Now a road runs past the village, but till the early 2000s, reaching Malana wasn’t easy. The 13-km trek from Jari took all day, and you weren’t allowed to stay overnight. Leather belts and wallets had to be left outside the village, locals didn’t shake hands with visitors, and if you touched a shrine, you had to pay a fine.

Yet, visitors kept trickling in. First came curious anthropologists. Welshman Colin Rosser spent two years here and published a paper titled ‘A hermit Village in Kullu’, in 1952. Then, after an Italian tourist taught Malanis how to produce good hand-rubbed charas, and their ‘Malana Cream’ won Amsterdam’s prestigious cannabis cup in 1995, the number of trekkers multiplied.

Change In Overdrive

But it was the road that brought change to this village in overdrive. “This road and two devastating fires changed the village forever,” says Kullu-based Rajeshwar Kyarpa, who has been researching Malana and Kanashi. “The road exposed Malanis to the outside world in a way nothing had before…it was a gamechanger,” he says.

The walk from the road takes less than an hour, and “all sorts of people come freely to the village and pollute the atmosphere in Malana. We are losing our old ways because of them,” says Beli Ram, a local shepherd.

When the boom started, Malanis had cashed in on it by building small hotels and restaurants within the village. But in July 2017, the council of Jamlu Devta – principal deity – barred outsiders from staying overnight. Only govt employees posted in the village can rent rooms there now. However, over 50 guest houses stand around Malana and in the nearby Magic Valley, where Malanis cultivate their prized cannabis. Even these guest houses are leased and run by people from the plains.

Old Ways Gutted

While the road brought the outside world to Malana, two major fires in Jan 2008 and Oct 2021 reduced its old self to ashes. “Malanis never again built wooden houses in the traditional kathkuni architectural style,” says Kyarpa. Most of the village’s 300-odd houses are now made of concrete, with satellite receivers on their roofs beaming the world into their living rooms. “It’s no longer the isolated village where outsiders were not welcome,” says Kyarpa.

When the road was built for a hydel project, Malanis had opposed it. Ironically, almost all of them own vehicles now, and some even run cabs with drivers hired from within the Parvati valley. Work was on to build another road right up to the village, but it had to be stopped after a massive landslide last year. “The road is not good for us,” says Beli Ram, the shepherd, but his voice might be in a minority now.

Women Head Out

Perhaps the biggest change is in marriage mores. Malanis have always been ‘endogamous’. Panjab University (PU) researchers published a paper in 1985 that said 93% of Malanis married within their village and the rest in nearby Rasol. Only 4 Malanis at that time had married outside Parvati valley. Now, many marriages happen with outsiders. Girls, especially, are stepping across the lines of village and caste. Some have moved within Himachal to Chamba district or other parts of Kullu, others have settled in faraway cities like Mumbai and Kolkata. At least one married Malana woman is settled abroad in the Netherlands.

Dalip Ram says 90 girls have married men from outside Malana and Rasol in recent years. “Our girls marry all these outsiders who come here looking for work or run the guest houses. Nobody stops them, but once they get married to these people, we don’t accept them as our own,” he says.

Malani men, however, still marry within the village or in nearby places. Many of them have married twice or thrice and have 5-6 children from different marriages. “Malani men don’t mingle much with other people of the valley, and not many women would be keen on settling down at a place with a culture and language so different from theirs,” says a schoolteacher in Malana who doesn’t want to be named.

Flouting Divine Orders

Jamlu Devta is omnipotent in Malana, and like ancient Greek gods, he speaks to Malanis through an oracle – his council. You can read his writ on notices stuck outside temples. The fine for touching a holy place can be up to Rs 5,000. But it’s another sign of social change that Malanis don’t follow Jamlu Devta’s commands to the letter anymore.

A few years ago, the council banned liquor and DJs at weddings. More recently, it banned energy drinks. But Malanis just pay a fine to the council and do as they will.

“People throw parties, consume liquor, have DJs at weddings for days, and then pay the fine – sometimes lakhs of rupees – to the council, which is happy to have the money and doesn’t worry about its fading clout,” says Chhape Ram Negi, a veteran rescue expert who has lived in Malana for more than 40 years. He says fines are almost a status symbol now, with Malanis vying with each other to break council rules and pay heftier fines. “There is competition among the villagers.” Recourse to police in village disputes has also undermined the council’s authority. Traditionally, Malanis went to the court of Jamlu Devta, a practice conso- nant with their ‘oldest democracy’ tag. “Yes, many in the village have approached police and courts for solving their issues,” says Malana’s pradhan Raju Ram, adding, “You can’t force people to follow village customs if they don’t want to.”

Village Of Crorepatis

Negi, the rescue expert, says easy money from cannabis has changed Malanis more than the road and the visitors. “Addiction to easy money is destroying this unique culture and society from within. Except for a few elders, nobody is bothered about preserving the unique heritage of Malana.” Malanis consider charas a gift from the gods and most have cannabis farms in Magic Valley. Many sell Malana Cream, which costs Rs 2,500-10,000 per 10g, depending on quality, to visitors.

“If you earn up to Rs 1 lakh a day selling charas, without stepping out of the village, why would you do anything else?” says the anonymous village teacher. “One reason for opposing the road was that it made Malana accessible to the cops as well. Unlike other parts of Parvati valley, Malanis don’t grow fruit and other crops. It’s impacting their children in a bad way… They start earning while in school.”

Sometimes, locals are arrested for smuggling charas, but it doesn’t bother anyone. The teacher says about 275 children study at Malana’s primary and senior secondary schools, but few leave the village to look for work. “So far, only 3-4 Malanis have joined govt service.”

‘Change Is Inevitable’

Anthropologists are still studying Malana’s origins. It’s been long speculated that the village was founded by a detachment of Alexander’s army, which could make it about 2,300 years old – an incredibly long time for a culture to survive unchanged. But independent filmmaker Amlan Dutta, who made Bom, a 2011 documentary on Malana, says change is inevitable and it shouldn’t be considered bad. “People of Malana must know the outside world and learn how to deal with it. It’s in their hands to protect their uniqueness.”

Researchers also say it’s a matter of time before the village gets mainstreamed. Professor Kewal Krishan, who teaches at PU’s anthropology department, agrees with Dutta that the forces of modernisation are irresistible. “But the important thing is how much of their precious and unique culture the people of Malana will manage to save and protect in the end,” he says.

Ancient Council & Court

All judicial and religious authority of Jamlu Devta rests with an 11-member council, which has three permanent members and eight elders elected by villagers. It governs the village and acts as the court of Jamlu Devta. Traditionally, Malanis took their disputes to this court, held in the open on stone platforms outside the Jamlu temple. The guilty party had to pay a fine fixed by the court, and was sometimes ostracised.