Malaria: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

History

Prehistoric India had anti-malaria system

January 6, 2021: The Times of India

When the first humans started moving out of Africa 350,000 years ago, they looked for dry areas because tropical regions were home to malaria-carrying mosquitoes. So, why prehistoric humans entered India 70,000 years ago has puzzled scientists. But a new study offers an answer. “India’s medical system was able to take up the fight against diseases thousands of years ago, while in other malariahit areas, a similarly effective, Ayurveda-like system didn’t exist,” Dr Attila J Trájer, lead author of the study, told Chandrima Banerjee.

‘Malaria bug in prehistoric India may have been benign variant’

The malarial parasite in prehistoric India is likely to have been the more benign variant, according to the study published in ‘Quaternary International’.

The study, by scientists from the Sustainability Solutions Research Lab at the University of Pannonia and funded by the Hungarian government, examined why ancient humans preferred dry and arid areas. They studied 449 archaeological sites, 94 of which are in India, to understand what determined the settlement and migration patterns out of Africa. “It seems mosquito-borne diseases, like malaria, could have a strong effect on the population dynamic of ancient humans,” Trájer said.

Malaria-carrying mosquitoes are believed to have appeared between 28.4 and 23 million years ago, long before humans. “It is almost certain that the common ancestor of humans and primates had at least one malaria parasite,” said Trájer. “As in the present times, it is plausible that malaria caused high mortality among children under 5 year and pregnant women.” Which means malaria parasites evolved with humans and apes, and biological factors were as important as climate in charting the course of humans across the face of the planet. The movement towards South Asia, about 60,000 to 70,000 years ago, consequently, was an aberration.

Incidence of Malaria

2009

Half the world at risk of malaria: WHO

Of 243M Cases Across Globe In 2009, 863000 Died; Africa Accounts For 90% Of Infections

The news from the frontline is mixed on World Malaria Day today. While the UN affiliated World Health Organisation (WHO) and several private agencies are cautiously optimistic because of recent decline in reported malaria cases and an increased flow of funds for fighting malaria, others, including the leading health journal Lancet are pointing at the looming clouds of drug resistance and lack of suitable vaccine for this ancient killer disease.

Malaria, along with tuberculosis, continues to be one of the world’s most lethal diseases with half the world’s population — about 3.3 billion people — at risk from it, according to the latest World Malaria Report 2009, released by WHO last December. Over 243 million confirmed cases of malaria were reported from across the world, of which an estimated 863,000 died. The biggest burden of malaria is borne by Africa with nearly 90% of cases, most being children below 5 years.

In India, while there has been proportional reduction in the number of cases, the numbers are still huge. From over 2 million reported cases in 2000, confirmed malaria cases dropped to about 1.51 million in 2007, but then showed an upward tick in the next two years to reach 1.53 million in 2009, according to provisional estimates of National Vector Borne Diseases Control Programme of the health ministry.

Experts believe that these are gross underestimates because the reach of testing facilities is limited and large numbers are going unreported.

In the World Malaria Report, WHO director general Margaret Chan struck an optimistic note saying that global funding for fighting malaria had jumped from a commitment of $300 million in 2003 to $1.7 billion in 2009. As a result, coverage with insecticide treated nets (ITN) increased from 17% to 31% while population covered by indoor residual spraying of insecticide increased from 14 million to 59 million. Testing for malaria and treatment with the new artemisinin combination therapy (ACT) too has increased substantially.

In 2006, WHO issued new guidelines for tackling malaria that include mandatory testing before prescribing drugs. This is to prevent the growing threat of resistance of the malarial parasite to these drugs if given indiscriminately. Quinine based drugs have already gone out of favor because of widespread resistance to it.

In India too, one variety of malarial parasite was found to have developed resistance to chloroquine in 117 highly endemic districts of 7 North Eastern states and Andhra Pradesh, Chhatisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh and Orissa.

As the resilient malarial parasite battles it out with medical science across the world in a do or die battle, there are some ominous signs on the horizon. Starting with studies in Cambodia, and then from several pockets in other parts of the world, resistance to the new artemisinin based drugs has been reported. According to an editorial in Friday’s edition of Lancet, “There is currently no new drug class for treatment in advanced development”. In other words, if resistance to artemisinin spreads, like it did for chloroquine, the global fight against malaria would be lost.

2013-17: deaths dip 50%

Oct 18, 2019: The Times of India

India has presented the “biggest success story” amongst malaria endemic countries in the world as malaria cases and deaths have declined by almost 50% in five years between 2013 and 2017, an official statement said after the Cabinet was apprised of the progress under the health ministry’s flagship National Health Mission.

While malaria cases dropped by 49.09%, deaths from the disease declined by 50.52% in 2017, as compared to 2013.

The maternal mortality ratio (MMR) and under-five mortality rate (U5MR) also declined since 2005 and at the current pace, India should be able to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) targets much before 2030, the statement said.

The under-five mortality rate (deaths per 1,000 live births) declined from 69 per 1,000 live births in 2008 to 37 per 1,000 live births in 2017.

During the same period, infant mortality rate (number of deaths per 1,000 live births of children under one year of age) at national level declined from 53 to 33.

The maternal mortality ratio dropped from 254 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2004 to 130 per 100,000 live births in 2016.

Under the SDG, the world has committed to trying to bring MMR to 70 deaths per 100,000 live births by 2030 and the under-five mortality rate to 25 deaths per 1,000 live births. The government said the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme has been significantly strengthened and intensified. A total of 1,180 cartridge-based nucleic acid amplification test machines across all districts have been installed, which provides rapid and accurate diagnosis for tuberculosis, including drug resistant TB.

2016

4,443 malaria cases in Mewat since June – Sept 2016

A mid the din and hurt sentiments that the Haryana government's biryani policing generated in Mewat, a malaria threat sweeping through the district has gone virtually unnoticed and, going by the government's own figures, unchecked.

Since June, Mewat has recorded 4,443 cases of malaria, which accounts for two-thirds of the 6,695 cases reported across Haryana.Around 90% of the posts in Mewat's health department lying vacant. “The reason why we are unable to tackle this menace is because there are hardly any medical resources,“ said a health department official.

2017: cases decline by 24%

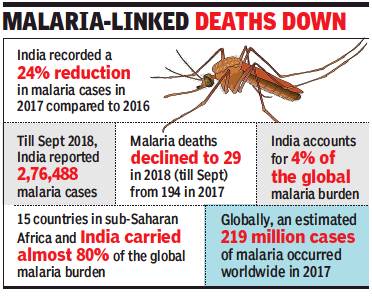

From: Sushmi Dey, India closer to malaria-free tag, cases dip by 24% in a yr, November 20, 2018: The Times of India

3 Million Fewer Cases Between 2016 And 2017

Marking significant progress in the fight against malaria, India recorded nearly 24% decline in cases in a year between 2016 and 2017, the only one among the 11 highest-burden countries to achieve so, says the latest World Malaria Report.

Deaths due to malaria have also dropped significantly to 194 in 2017 from 331 in the previous year, says the 2018 report. However, with 4% of global cases, India continues to account for the highest malaria burden outside sub-Saharan Africa.

“The 10 highest burden countries in Africa reported increase in cases of malaria in 2017 compared with 2016. Of these, Nigeria, Madagascar and Democratic Republic of Congo had the highest estimated increase, all more than half a million cases. In contrast, India reported 3 million fewer cases in the same period, a 24% decrease compared with 2016,” says the World Health Organisation report.

India plans to eliminate malaria by 2027, three years ahead of the global target and has also formulated an action plan.

According to latest figures available with the health ministry’s National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme, till September this year, 2,76,488 cases of malaria were reported in the country, whereas mortality declined to double digit at 29 deaths till two months ago.

Globally, there were an estimated 219 million cases of malaria in 2017, whereas deaths reached 4,35,000 in the same year. In India, three states — Odisha, Chhattisgarh and West Bengal, which account for a major burden of malaria cases — reported a substantial decrease.

2019: decline

December 3, 2020: The Times of India

WHO: Sharp dip in malaria cases in India in 2019

New Delhi:

India has made considerable progress in reducing its malaria burden and is the only high endemic country to have reported a decline of 17.6% in cases during 2019 as compared to the previous year, says the World Malaria Report 2020 by World Health Organisation. India also witnesses the largest absolute decline in WHO’s South-East Asia region, though it still accounted for 88% of malaria cases and 86% of related deaths in the region. In India, between 2000 and 2019, malaria cases dropped by over 83% to around 3.38 lakh, whereas deaths declined by 92%. Cases and fatalities have declined a significant 21.3% and 20%, respectively, in 2019 from a year ago. TNN

Malaria cases till Oct fell by 45% against last year’s count

Total number of malaria cases reported till October this year fell 45% year-on-year, the government said. States like Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Meghalaya and MP together accounted for nearly 45.4% of total malaria cases in the country in 2019. They were also responsible for 63.6% malaria deaths.

The government intensified malaria elimination efforts with the launch of the National Framework for Malaria Elimination in 2016. It was followed by the national strategic plan for malaria elimination (2017-22), launched by health ministry in July 2017, which laid down strategies for next five years.

In 2019, global malaria cases stood at 229 million, an estimate that has remained unchanged over the last four years. The deaths from the disease have dropped slightly to around 4.09 lakh in 2019 compared to 4.11 lakh in 2018.

2015>2023

DurgeshNandan Jha, Dec 27, 2024: The Times of India

New Delhi : The number of states/UTs falling with high malaria burden in India has come down from 10 in 2015 to two in 2023, latest data shared by the health ministry shows. A state/ UT is considered to have ‘high burden’, also referred to as category 3, if it has more than one malaria case per 1,000 population under surveillance.

According to the health ministry, from 2015 to 2023, numerous states have transitioned from the higher-burden category to the significantly lower or zero-burden category. In 2015, the ministry said, 10 states and UTs were classified as high burden (Category 3), of these, in 2023 only two states (Mizoram & Tripura) remain in Category 3, whereas four states such as Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, and Meghalaya, have moved to Category 2.

A state/UT is considered to fall under ‘category 2’ if it has less than 1 malaria case per 1,000 population under surveillance, but some districts have higher disease prevalence. Latest data shows four states, namely, Andaman & Nicobar Islands, MP, Arunachal, and Dadra & Nagar Haveli have moved to Category 1 – when a state has less than 1 case across all districts.

2024: Bhutan, India, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka

Anuja.Jaiswal, Dec 6, 2025: The Times of India

New Delhi: India remains the centre of malaria transmission in the WHO South-East Asia Region, accounting for 73.3% of all estimated cases and nearly 89% of malaria deaths in 2024, even as the region records one of the world’s steepest declines in malaria, World Malaria Report 2025 showed.

The region logged 4.79 lakh cases in 2024 — a 65.7% fall since 2015 — and just 99 reported deaths, but WHO estimates indicated a far larger burden of 2.7 million cases and 3,900 deaths, with India driving most infections and fatalities. Despite this dominance, India remains on track to meet the 2025 Global Technical Strategy goal of a 75% drop in incidence, having crossed a 70% reduction by 2024. Most districts continue to report sustained declines, though localised outbreaks in forest belts and cross-border spillover from Nepal persist as major challenges.

Children under 5 accounted for 8.7% of cases and 18% of deaths, while P.vivax, notoriously difficult to eliminate, caused nearly two-thirds of infections. The report credits the gains to aggressive interventions — large insecticide-treated net drives in India, Myanmar and Nepal; 143% growth in rapid testing since 2015; and 100% treatment coverage. Low-level pfhrp2/3 gene deletions were detected in India, but treatment failure for key ACTs remained below 5%, indicating continued drug efficacy.

A key milestone highlighted was India’s exit from High Burden to High Impact group in 2024, marking its shift from a global high-burden nation to one nearing elimination in several states — a transformation few countries have achieved at this scale. Bhutan, Sri Lanka and Timor-Leste are malaria-free. WHO warns drug resistance, climate-related outbreaks and declining international funding threaten global progress.

Dr Sunil Rana of Asian Hospital said malaria persists in India because timely healthcare fails to reach tribal and forest communities. “Longer mosquito-breeding seasons, delayed care-seeking, weak surveillance and unchecked migration through border zones keep outbreaks alive,” he said.

Court verdicts

Death by mosquito is not insurable: SC

Krishnadas Rajagopal, March 26, 2019: The Hindu

National Insurance Limited argued that a mosquito bite cannot be classified as a ‘personal accident’ covered under the policy.

Is death by mosquito bite insurable as a ‘personal accident’? Well, not if the mosquito bit the insured person in the Republic of Mozambique, the Supreme Court held on Tuesday in a judgment.

The case concerns the death of a man, Debhashis Bhattacharjee, who died of multiple organ failure after being diagnosed with encephalitis malaria contracted from a mosquito bite he sustained while working in Mozambique in 2012.

His insurance policy covered personal accidents. Both the State and the National Consumer Dipsutes Redressal Commissions dismissed the plea made by the insurance company, National Insurance Limited, that the man died as a result of an infection. The company had argued that a mosquito bite cannot be classified as a ‘personal accident’ covered under the policy.

The insurance company, represented by advocate Madhavi Divan, said death due to malaria was a common occurrence in Mozambique. Ms Divan adverted to the World Health Organization’s World Malaria Report 2018, which showed that an estimated ten million cases of malaria in Mozambique and an estimated 14.7 thousand deaths in the year 2017.

A Bench led by Justice D.Y. Chandrachud disagreed with the conclusions of both the Consumer Disputes Commissions. In fact, the State Commission had held that it would be “rather silly” to call a sudden death due to mosquito bite in a foreign land a natural death and not an accident. The National Commission too had agreed that if the insurance company could cover events like snake bite, frost bite and dog bite then why not mosquito bites.

In his 16-page judgment, Justice Chandrachud acknowledged that being “bitten by a mosquito is an unforeseen eventuality”.

However, the mosquito bit Mr. Bhatacharjee in Mozambique, which according to World Health Organization has a population of 29.6 million people and accounts for five per cent of the cases of malaria globally.

Malaria is too common in Mozambique. “It is on record that one out of three people in Mozambique is afflicted with malaria. In light of these statistics, the illness of encephalitis malaria through a mosquito bite cannot be considered as an accident. It was neither unexpected nor unforeseen. It was not a peril insured against in the policy of accident insurance,” Justice Chandrachud set aside the decisions of the Consumer Disputes Commission.

Research on Malaria

How malaria affects the brain

December 16, 2020: The Times of India

Team co-led by Indian scientists solves 100-year-old mystery of how malaria affects brain

NEW DELHI: Using brain imaging techniques, scientists, including those from The Center for the Study of Complex Malaria in Odisha, have unravelled the century old mystery of how malaria affects the brain, an advance which reveals how the deadly disease causes different outcomes in adults and children.

According to the researchers, cerebral malaria is a severe, life-threatening complication of infection with the Plasmodium falciparum parasite that can infect humans through the bite of Anopheles mosquitoes.

While a fifth of people with this form of the disease die despite treatment, and neurocognitive after-effects are common in survivors, they said the effects of malaria on the brain have puzzled scientists for the last 100 years.

The study, published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases on Wednesday, used cutting-edge MRI scans to compare the changes in the brains of survivors with those who died from the disease across different age-groups.

"For years, scientists have relied on autopsies to understand the pathology of cerebral malaria, but these don't allow you to compare between survivors and fatalities," said Sam Wassmer, a co-lead author of the study from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) in the UK.

"By using neuroimaging techniques to see a snapshot of the living brain, we were able to identify the specific cause of death in adults," Wassner said.

In the study, the scientists assessed 65 patients with cerebral malaria and 26 control patients with 'uncomplicated' malaria, who were being treated at Ispat General Hospital in Rourkela.

They found that brain swelling tends to decrease with the age of the patient, and that, unlike in children, there was no correlation between brain swelling and death in adult patients from the same cohort.

Instead, the researchers said fatal adult cases had severe oxygen deprivation affecting all brain structures, compared to only localised oxygen-deprivation in survivors.

They said the findings were corroborated by significantly elevated levels of specific molecules in the blood which indicate oxygen-deprivation.

Based on the results, the researchers believe a system could be developed for the identification of patients at risk of developing fatal disease upon admission that could inform their clinical management.

"The results suggest the tantalising prospect of targeted treatments for cerebral malaria, and we are now planning clinical trials to test whether adjunctive therapies for oxygen-deprivation are effective for adults," said Sanjib Mohanty, study co-lead from the Centre for the Study of Complex Malaria.

"If successful, this could be a significant step toward reducing the death toll of one of the world's most deadly diseases," he added.

Vivax: Changes and increase

2011-15

The Times of India, Jul 31 2015

`Malaria's P. vivax strain threat to India'

Sushmi Dey

A particular strain of malaria parasite, which was believed to be less fatal, is now causing high disease burden, latest assessment by the World Health Organization shows.

While asking India to strengthen its strategy for elimination of malaria, the agency said countries need to focus more on P.vivax, which was so far known as less fatal but as the latest data shows the risk from the parasite is increasing.

India, in particular has witnessed a huge growth in the number of malaria cases due to P.vivax. In 2013, there were an estimated 15.8 million symptomatic cases of P.vivax malaria globally . Out of this, two-thirds occurred in the south-east Asia region which includes India, according to a latest WHO report on control and elimination of P.vivax malaria.

Though, the report doesn't provide specific number of P.vivax cases found in India, WHO said in a statement that India is a major contributor to the cases found in south-east Asia.

Separately , the Union health ministry's assessment under the National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme shows that there is a slight dip in the malaria cases due to P. falciparum parasite, known to be more fatal. According to a health ministry official, over 50% of total malaria cases in India are triggered by P.vivax. “Our efforts so far focused on the most deadly P.falciparum malaria. We need to now broaden our strategy to include targeted interventions for P.vivax malaria, which is contributing to a large proportion of global malaria burden, mainly in the WHO south-east Asia region,“ said WHO regional director Poonam Khetrapal Singh. WHO is hosting a global malaria meet in New Delhi to address the rising threat of P.vivax.