Mangala or Barber: Deccan

Contents |

Mangala or Barber

This article is an extract from THE CASTES AND TRIBES OF H. E. H. THE NIZAM'S DOMINIONS BY SYED SIRAJ UL HASSAN Of Merton College, Oxford, Trinity College, Dublin, and Middle Temple, London. One of the Judges of H. E. H. the Nizam's High Court of Judicature : Lately Director of Public Instruction. BOMBAY THE TlMES PRESS 1920 Indpaedia is an archive. It neither agrees nor disagrees |

Mangala, Hajam, Nhavi, Napik, Warik, Mahali, Nayadaru— the barber caste of Telangana descended, according to Manu, from a Brahman father and a Shudra mother. The name Mangala (auspi- cious seems to have reference to the barber's presence which, in his professional capacity, is indispensable at the commencement of Hindu ceremonial acts.

Origin

A variety of legends are current regarding the origin of the caste. According to one, they are the descendants of one Mangal Mahamuni, who was created by the_ Trinity (Brahma, Vishnu and Mahadeo) from their foreheads, to serve as a barber. Another version is that he was created by Brahma from a lotus flower. A third tradition says that as there was no barber in the world, the serpent king, Wasuki, was called upon by Shiva to issue from out his (Shiva's) navel to supply the want, and the barbers, as his descendants, called themselves Napik, a variant of Nabhik (navel- bom). One story ascribes their creation to the divine architect Vishwakarma.

Internal Structure

The Mangalas are divided into the fol- lowing five sub-castes : — (1) Konda or Sajjan Mangala, (2) Shri Mangala, (3) Raddi Mangala, (4) Maratha Warik, (5) Lingayit Warik. The name Konda, which means a ' hill ' in Telugu, throws no light upon the origin of the sub-caste. The members of the Konda Mangala sub-caste ascribe their origin to Ayoni Mathudu, or Kalyan Bhiknodu, who sprang from the third eye of Mahadeo. They claim to be of higher rank than the members of the Shri Mangala caste, who are supposed to be the offspring of a man begotten by a Konda Mangala man and a Balija woman. The three sub-castes, Konda, Shri and Raddi Mangalas represent the barber class of Telangana.

The Maralha Wariks are indigenous to Marathawadi districts. In their features, customs, and even in their exogamous sections, the Maratha Wariks closely resemble the Maratha Kunbis and may on this account be regarded as a functional group formed out of the Kunbi caste.

Lingayit Wariks are chiefly found in the Kamatic. They claim to be descended from Udupati Anna, who used to shave Basava and viai his favourite disciple. The Linga,yit Wariks are sub-divided into two groups ; the one is thoroughly influenced by the Jangams, the other only partially so influenced but still attached to their original customs and usages, eating flesh, burning their dead and obs€rving mourning for eleven days instead of nine.

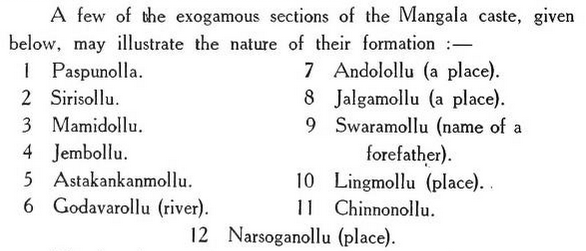

A few of the exogamous sections of the Mangala caste, given below, may illustrate the nature of their formation : —

The first three sections are common to them and to the Kapus, and may have been borrowed from the latter. The remaining appear to have been recently introduced, having reference to the names of their forefathers or to the names of places which they occupied.

The rule of exogamy is that a man cannot marry outside his sub-caste nor within the section to which he belongs. He can marry his wife's younger sister and his maternal uncle's daughter, but cannot marry his aunt or his first cousin. Members of higher castes are admitted into that of the Mangalas, no special ceremony being performed on the occasion. Women excommunicated for adultery or other offences from the higher castes, such as Kapu, Munnur, Mutrasi, Sali, &c., find admittance into this caste and enjoy all the rights of a Mangala woman.

Marriage

The Mangalas marry their daughters as infants, between the ages of five and twelve. The marriage ceremony corres- ponds to that of the Kapu caste. After a suitable match has been fixed upon and the preliminary negotiations have been completed, a formal visit is paid by the bridegroom's parents for the purpose of seeing the. bride. The parents of the bride then return the visit to see the bridegroom. An auspicious day for the wedding is then fixed. A fortnight before the ceremony, Pinnamma, the goddess of Fortune, is v^forshipped and her blessing is invoked on the couple. The bridegroom's people then proceed to the village of the girl, present her with a new sari and choli, adorn her with jewels and put the Prathan ring on her litfle finger. After paying Rs. 15 to the bride's parents (bride price), the party return, taking with them the bride and her people. A marriage booth is then erected, consisting of 6 posts, one post being of Umber {Ficus glomerata). The marriage ceremony is generally performed in the bride's pandal, but if the peirents of the bride are poor, it is celebrated in the bride- groom's. Early on the wedding day, mortars and grind-stones are worshipped by five married females, and turmeric and rice are ground to symbolise the preparation of the wedding articles. This ceremony is known as' Kotanum. Arveni Kundalu follows, in which earthen vessels, painted white, are brought under a canopy from the potter's house and deposited in the room dedicated tO' the household gods, in which auspicious lights are lit and kept burning constantly throughout the ceremony. The bridal pair, seated on a yoke in the midst of four earthen pots, encircled with five rounds of cotton thread, are then besmeared with turmeric and oil and bathed by a barber, who also pares their nails and claims their wet garments as his fees. After changing their wet clothes for bridal garments, the couple are taken before the household gods and made to worship the deity and the Arveni Kundalu vessels. Decked with bashingams, they are subsequently brought to the marriage booth and made to stand on a yoke facing each other with a screen held between them. Led by the Brahmin priest reciting benedictory verses, the assembly shower coloured rice on the heads of the couple and bless them. The subsequent ceremonies performed by the bridal couple are (i) Jelkatbelam, i.e., putting the mixture of cumin seed and jaggery on each other's heads, (ii) Padghattamm, each treading the other's foot.

(iii) Pusti, tying of the auspicious string by the bridegroom round the bride's neck, (iv) Kankanam. wearing thread bracelets, (v) Thalwal, throwing turmeric coloured rice on each other's heads, (vi) Karrsdddn, formal gift of the bride by her father to the bridegrpom, (vii) Brahmdmudi, tying the ends of the garments of the bridal pair in a knot, and lastly (viii) Arundhati Darshan, looking at Arundhati, represented by the pole star. The bride and bridegroom make obeisance to the family gods and the elders and are then given milk and curds to drink. The shastriya rites are thus brought to a close, the tying of the ' pusti ' and the formal giving a\vay of the bride (kanyadan) by her father forming the essential and binding portions of the ceremony. Generally on the 14th day the ceremony of NagWeli is performed. Unhusked rice is spread on the ground in the form of a square with four earthen pots on the corners. The pots are encircled five times with a raw cotton thread. On the lice are placed the Arveni Kundalu pots and twelve platters of leaf, containing heaps of food crowned by lighted lamps. The wedded pair worship the sacred pots and the bridegroofn, taking a dagger in his hand, makes, with his bride, three turns round the polu. This ceremony is also known as "Talabalu." The bridegroom, carrying the shaft of a plough and a rope, walks a little distance and ploughs a piece of ground into furrows in which he sows seeds. While thus occupied, his child bride brings him some rice gruel to drink. The marriage is completed by (i) Pdnpu, in which the young pair are made to play with a wooden doll, a mimic drama of their future life, (ii) Vappaginthd, which makes over the bride to the care of her husband and his parents and (iii) Vadibium, in which the girl IS presented with rice, cocoanuts, fruit and other presents. Polygamy is permitted and no restriction is imposed upon the number of wives a man may have.

Widow-Marriage

A widow is allowed to marry again, but not the brother of her late husband and in her choice of a second husband, she must not infringe the law of exogamy. Previous to the marriage, one rupee is given to the widow to enable her to purchase bangles and metalla (toe-rings). In the evening the widow goes to the house of her husband-elect and puts on new garments. A pusti (a string of black beads) is then tied round her neck, and cocoanuts, rice and dates« are presented to her. This marriage is termed Udki, or 'Chira Ravike.'

Divorce

Divorce is recognised and wives committing adultery, or not agreeing with their husbands, are divorced. The divorced women are allowed to many again by the same rites as widows. Adultery committed with a member of a higher caste is tolerated and may be punished slightly ; but a woman taken in adultery with a low casteman becomes outcaste.

Inheritance

The Mangalas follow the standard Hindu Law of Inheritance. The usage of Chudawand prevails among this caste, as among the other castes of Telangana. Females can inherit in default of male issue.

Religion

The religion of the Mangalas differs very little from that of the Kapus, or other Telugu castes of the same social standing. They are either Namdharis, worshipping Vishnu in the form of Narsinhlu, or are Vibhutidharis and pay reverence to the God Siva. For religious and ceremonial purposes they employ Brahmins, who incur no social degradation on that account. The local deities, Pochamma, Ellama, and Mhaisamma are propitiated on Sundays and Thursdays wilii offerings of fowls, sheep and sweetmeat, a Kumar or a Chakia officiating as priest. On Ganesh Chauth, the 4th of the lunar half of Bhadrapada (August-September), they honour the tools of their profession (razors, scissors, mirrors, &c.), when offerings are made of sweet dainties, which must contain the vegetable Tarrini wa (Leucas Cephalotes). At a funeral ceremony a Satani is called in by the Namdharis and a Jangam by the Vibhutidharis.

Disposal of the Dead

The dead are buried or burned in a lying posture with the head to the north and face to the east. Mourning is observed 10 days for married adults and 3 days for unmarried or for children. The ashes are either thrown into a river or a tank that is handy, or buried under a ' TarWad ' tree {Cassia auriculata), a platform being raised over them. On the last day of Bhadrapad they pour ' Til ' libations (Tilodak) in the name of the departed. Lingayit barbers bury their dead in a sitting posture and call in a Jangam to perform the funeral rites.

Social Status

The social status of the barber caste, accord- ing to Manu, was as high as that of the cultivators. From this position the barber of the present day seems to have fallen, for socially the Mangala of these dominions rank below the Kapus, Munnurs, Mutrasis and all shepherd classes. They eat mutton, pork and the flesh of fowls, cloven-footed animals and both varieties of fish. They also eat the leavings of high caste people and indulge freely in spirituous liquors.

Occupation

Shaving, which has been the traditional occupa- tion of the caste, includes nail-paring, 'shampooing and "cracking " the joints of the body. A village barber is not paid in cash but in grain, the quantity of which is settled for each plough, or he depends upon the annual produce of each farm. The usual charge for a shave in town is one anna.

The barber is also the village chirurgeon and prescribes for small complaints. In the capacity of surgeon he opens boils and abscesses, cups and treats gangreneous parts. His wife also plays an im- portant part as a midwife and nurse.

At Hindu weddings barbers are engaged as musicians, playing on drums and pipes (sanai), and as torch-bearers; they are not known to have lost their social status on this account.