Meghalaya

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

The source of this section

INDIA 2012

A REFERENCE ANNUAL

Compiled by

RESEARCH, REFERENCE AND TRAINING DIVISION

PUBLICATIONS DIVISION

MINISTRY OF INFORMATION AND BROADCASTING

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA

Meghalaya

Area : 22,429 sq km

Population : 29,64,007 (Prov. 2011 Census)

Capital : Shillong

Principal Languages : Khasi, Garo and English

HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY

Meghalaya was created as an autonomous State within the State of Assam on 2 April 1970. The full-fledged State of Meghalaya came into existence on 21 January 1972. It is bounded on the north and east by Assam and on the south and west by Bangladesh. Meghalaya literally means ‘the Abode of Clouds’ and is essentially a hilly State. It is predominately inhabited by the Khasis, the Jaintias and the Garos tribe communities. The Khasi Hills and Jaintia Hills which form the central and eastern part of Meghalaya form an imposing plateau with rolling grassland, hills and river valleys. The southern face of the plateau is marked by deep gorges and abrupt slopes, at the foot of which, a narrow strip of plain land runs along the international border with Bangladesh.

AGRICULTURE

Meghalaya is basically an agricultural State in which about 81 per cent of its population depends primarily on agriculture for their livelihood. The State has a vast potential for development of horticulture due to the agro-climatic variations, which offer much scope for cultivation of temperate, sub-tropical and tropical fruits and vegetables.

Besides major food crops of rice and maize, Meghalaya is renowned for its orange (Khasi Mandarian), pineapples, bananas, jackfruit, temperate fruits like plum, pear and peach, etc. Cash crops, popularly and traditionally cultivated include potato, turmeric, ginger, black pepper, arcanut, bedeviling, tapioca, short staple cotton, jute and mesta, mustard and rapeseed. Special emphasis is presently being laid on non-traditional crops like oilseeds (groundnut, soyabean and sunflower), cashewnut, strawberry, tea and coffee, mushroom, medicinal plants, orchids and commercial flowers.

INDUSTRIES

The Meghalaya Industrial Development Corporation Limited, as the Industrial and Financial Institution of the State, has been rendering financial assistance to the local entrepreneurs. District Industries Centres have been working in the field for the promotion and development of small-scale, village, tiny and cottage industries. A number of industrial projects have been set up for the manufacture of iron and steel materials, cement and other industrial products.

FESTIVALS

A five-day-long religious festival of the Khasis ‘Ka Pamblang Nongkrem’ popularly known as ‘Nongkrem dance’ is annually held at Smit village, 11 km from Shillong. ‘Shad Sukmynsiem’, another important festival of the Khasis is held at Shillong during the second week of April. ‘Behdeinkhlam’, the most important and colourful festival of the Jaintias is celebrated annually at Jowai in Jaintia Hills in July. ‘Wangala festival’ is observed for a week to honour Saljong (Sungod) of the Garos during October – November.

Behdieñkhlam

Behdieñkhlam is the most important festival of the Pnars in both the East and West Jaintia hills District of Meghalaya. The term Behdieñkhlam is made up of three words. In the Pnar parlance, ‘Beh’ literarily means to chase or to rid off, ‘dieñ’ means wood or log and ‘khlam’ means plague, epidemic or pestilence. Therefore Behdieñkhlam literarily means the festival to rid away plague. To define Behdieñkhlam by merely using the literary meaning of the festival is like describing the book by simply looking at its cover because that is not what Behdieñkhlam is all about; in fact it is more than chasing away plague.

There are altogether 6 annual Behdieñkhlam festivals celebrated by the Pnars of different communities called Raids. The first Behdieñkhlam was celebrated by the raid Chyrmang, followed by the raid Jowai, Tuber, Ialong, Mukhla and raid Muthlong.

The main part of the festival is the Council of the 4 high priest of the four raids, the raid Jowai, raid Tuber, raid Chyrmang and Ialong. K C Rymbai former Daloi of the elaka Jowai confirmed that the festival indeed has a fine connection with the agricultural activities of the people. Every part of the rituals performed throughout the year in preparation of Behdieñkhlam are intricately linked to agriculture. It is after the ritual ‘Thoh Langdoh’ is performed that people can start planting cucumber, pumpkins, beans and various types vegetables and it is only after another ceremony ka ‘Chat thoh’ that farmers can start tilling their paddy fields.

The various Behdieñkhlam festivals celebrated by the different raid also indicate the many important events of rice cultivation. The first Behdieñkhlam is that of raid Chyrmang and it symbolises the onset of the season for tilling the paddy fields. Jowai Behdieñkhlam signifies the season after the seeds are placed on the lap of mother nature and the raid Tuber’s Behdieñkhlam coincides with the time that farmers are done with weeding, the raid Ialong celebrates its Behdieñkhlam when the rice plant starts to flowers while the celebration of the raid Mukhla’s festival indicates the advent of the harvest season.

Behdieñkhlam therefore is not merely about ridding off the plague but it testifies to the fact that the Pnars of Jaintia were the first tribe in the region to adapt to more developed farming practices.

The immediate rituals and sacrifices that precede the designated four days of the festival are the ‘kñia khang’ performed on Muchai; the first day after the market day of the week and ‘kñia pyrthad’ sacrifice to the thunder god on the Mulong the seventh day of the same week. But the festival officially begins on the sixth day (Pynsiñ) of the eight days a week traditional calendar of the Jaintias.

Though the main features of the festival celebrated by the different raids are the same yet there are some variations in the rituals performed. In Jowai; the three days and four nights annual Behdieiñkhlam festival always starts with the tradition of offering food to the ancestors in a tradition called, “Ka Siang ka Pha” or “Ka Siang ka Phur.”

The feast of offering food to the dead is a mark of veneration and gratitude to the ancestors the forebears of the clan and the tradition. In the Khasi Pnar concept of the afterlife, departed souls reside with the Creator and eat betel nut in the courtyards or corridors of God’s abode. The spirit of the dead (ki syngngia ki saret) every year, descend down to the Earth to partake in the feast provided by the descendants to propitiate the departed souls.

Ka Siang ka pha is celebrated by every clan except when there is sickness in the family or if death has just occurred in the family. The family which had just met with bereavement, does not perform the offerings because ‘ka siang ka pha’ has already been offered to the departed souls as part of the last rites of a person. But not all clans perform their offerings to the dead on Pynsiñ. There are also clans which perform ‘ka siang ka pha’ on Muchai the last day of the festival.

All kind of foods are placed in brass plates and they must always be in odd numbers 5, 7 or 9. Care is also being taken that the favourite food of the deceased is placed as part of the offering which could be anything from fruits and cigarettes to rice and curry etc. The next part of the rites lies on the maternal uncle to invoke the spirits to partake of the offering. After the Maternal uncle’s invocation the whole family gathered for the rites remains silent for sometimes in a symbolic moment to allow the ancestors’ spirits to consume the offerings. Then the offering is shared among the family members. Only a clean female member of the family is allowed to prepare the offerings, women who are in their menstrual cycle are not allowed to do the preparation.

In the traditional calendar “Mulong,” is the day before “Musiang the market day,” the market day in Jowai is also the third day of the fest. By the end of the day all the ‘dieiñkhlam’ 9 round neatly carved logs are kept at their allotted place at different locations in the Ïawmusiang market area. The Dieñkhlams are prepared by the 7 localities namely Tpep-pale, Dulong, Panaliar, Lumïongkjam, Loompyrdi Ïongpiah, Loomkyrwiang and Chilliang Raij being the khon Raij was by tradition given the responsibility to prepare and bring two round logs called ‘Khnongblai’ and ‘Symbood khnong’.

On this day all male members of the Niamtre march in a procession and dance to the traditional drums and flutes to bring the dieñkhlam from the forest to Ïawmusiang. Early in the morning families are busy preparing ja-sngi (lunch) for every male member of the society and they in turn get ready to join the community to bring the dieñkhlam.

The third day of the holy week is “Musiang” and on this particular day all the dieiñkhlam and the Khnong are carried from the heart of Jowai town to the respective localities. Apart from the 7 dieñkhlam and two khnongs, hundreds of 15 to 19 feet trees called ‘ki Dieñkhlam khian (small Dieñkhlam) are used by the followers of the Niamtre. Two or three of these tiny Dieñkhlam are kept in the frontage or veranda of every house of the followers of the Niamtre. The tiny Dieñkhlam are used to beat the rooftops of the house symbolizing the act of chasing away the plague and evil spirits from the house and pray to the almighty God to bless the family.

Muchai is the last day of the Behdieñkhlam festival of Raid Jowai. The day starts in the wee hours of morning with the tradition of ‘kyntiñ khnong’ at the Priestess’s official residence. The programme is followed by the Ka Bam tyngkong led by the Daloi at the clan-house of the first four settlers of Jowai town. But the main part of the festival is the coming together of all the khon (children) ka Niamtre at the sacred Aitnar, a pond in which the last significant part of the festival is performed.

The dance at Aitnar is that of the people who find joy on the arrival of U Tre Kirod (God) with the celebration of Behdieñkhlam. It also symbolizes the oneness of the people and everyone joyfully participates without any distinction. The ‘ïa knieh khnong’ traditions at the sacred pool is whence men compete to set foot on the ‘khnong’ which symbolizes cleansing of the souls and blessing for good health

The climax of the day is the arrival of the colourful Rots/rong brought by the many dongs of Jowai town to be displayed at the Aitnar, and all the beautiful rongs are then discard as part of the offering.

Dat Lawakor is the last public event of every Behdieñkhlam; it is to ask God to indicate which of the two valleys around Jowai, ‘the Pynthor neiñ or the Pynthor wah’ upper or lower valley will yield a good harvest this year. It is similar to football but using a wooden ball with no goal post. The only rule of the game is that the team which can carry the ball to the designated end wins and the particular direction will reap better harvest that year.

The last ritual to be performed by the Daloi, the Lyngdoh and the other religious dignitaries at the Lyngdoh’s residence is called ‘pynleit sarang’. To maintain the sanctity of the religious festival, self-purification by way of abstinence from sleeping with their partners is observed by religious head conducting the various rites during the entire festival. After the ‘pynleit sarang’ ritual; the Daloi and the other religious heads can now return to the homes of their respective wives.

Behdieñkhlam is therefore a festival which has many profound spiritual significances for the people.

TOURIST CENTRES

Meghalaya is dotted with a number of lovely tourist spots where nature unveils herself in all her glory. Shillong, the capital city, has a number of beautiful spots. A few of them are Ward’s Lake, Lady Hydari Park, Polo Ground, Mini Zoo, Elephant Falls, Shillong Peak overlooking the city and the Golf Course which is one of the best in the country.

TRANSPORT

Roads: Six national highways pass through Meghalaya for a distance of 606 kilometer.

Aviation: The only airport in the State at Umroi, is 35 km from Shillong.

GOVERNMENT

Governor : Shri Ranjit Shekhar Mooshahary

Chief Secretary : Shri W.M.S. Pariat

Chief Minister : Dr. Mukul Sangma

Jurisdiction of : Falls under the jurisdiction of High Court Guwahati High Court. There is a High Court Bench at Shillong.

AREA, POPULATION AND HEADQUARTERS OF DISTRICTS

District Area (sq km) Population Headquarters (Provisional Census-2011)

East Khasi Hills 2,748 8,24,059 Shillong

West Khasi Hills 5,247 3,85,601 Nongstoin

Ri-Bhoi 2,448 2,58,380 Nongpoh

Jaintia Hills 3,819 3,92,852 Jowai

East Garo Hills 2,603 3,17,618 Williamnagar

West Garo Hills 3,677 6,42,923 Tura

South Garo Hills 1,187 1,42,574 Baghmara

Bangladesh border

Villages on the border

Lack of a motorable road forces residents of Meghalaya's border villages to trade in takas and trek to Bangladesh for medical emergencies

It was love at first sight. But Nirman is a shy man not used to sharing his feelings in public so that's not how he describes the first time he met Dila. His version is more matter-of-fact: “I saw her and asked for her hand in marriage“. It's hard to get him to open up about his late wife. After a lot of prodding, he finally whispers a few details: she loved cricket, football and fishing; and she didn't want to die. But Dila did die because their village, Huroi in Meghalaya, has no motorable road.It was exactly two years and two months ago.She'd been in labour all night but her baby's head wasn't crowning. Finally, 15 villagers lifted her up in a blood-stained bedsheet, strung it across two bamboo poles, and began walking to a hospital in Bangladesh.

They carried Dila, who was screaming in pain and bleeding profusely, over a hilly terrain through the dense East Jaintia Hills forest while dodging the Border Security Force (BSF). While the Bangladeshi hospital in Kanaighat was just an hour away , the Umkiang primary health centre on the Indian side was a five-hour trek through the jungle. Driving to Umkiang over the `kacha' road would have taken seven hours.

Dila, who had lost her own mother as a child, died shortly after reaching the hospital. Before she lost consciousness, she begged her husband to be a good father to their six boys. For a long time, the youngest, who was three-years-old, would wake up at night to search for his mom.“Now, he doesn't remember her,“ says Nirman.

Huroi, where the couple lived, is one of four Indian villages that might as well be in Bangladesh. The others are Lejri, Lahalein (aka Lailong) and Hingaria. In these border villages, which have about 3,800 residents, people buy Bangladeshi goods with Bangladeshi currency (takas), call India from Bangladeshi SIM cards and rush to Bangladeshi hospitals during emergencies.Shops accept takas and double up as currency exchange kiosks. And villagers, most of whom know Bangla, admit that 70-90% of their income is in takas. We even met a nine-year-old named `Medical' after the hospital where he was born Osmani Medical College in Sylhet, Bangladesh.

The villagers would prefer to turn to India for their needs. But navigating the 35km unpaved stretch of the Sonapur-Borghat road that leads to these villages is a costly, time-consuming endeavour. During the monsoon, which lasts about six months, driving over this road is akin to manoeuvring a jeep through quicksand. Drivers double up as car mechanics, replacing parts and fixing oil leaks en route, and a team of six men, armed with shovels and tasked with pushing the car, accompany every vehicle.

A Rs 98-crore proposal to blacktop the Rymbai-Jalalpur road, which overlaps 15km of the `kacha' Sonapur-Borghat road, is awaiting an environmental impact assessment report. And plans to repair the Sonapur-Borghat road haven't progressed beyond a concept paper. Neither the area's MLA nor the district's deputy commissioner can provide even a rough timeline for these projects. But work on a border fence is racing along, restricting Lahalein and Lejri's access to Bangladeshi markets.

Since their inception, the economy of all four villages has rested on the sale of betel nut and paan leaves to Bangladeshi traders, who pay in takas. Villagers then use this Bangladeshi currency to pay for clothes, food even hens that are smuggled across the border by Bangladeshi salesmen. Indians know they are at a disadvantage in this trade because the Bangladeshis set the exchange rate; but without a `pakka' road, villagers feel trapped into accepting their terms.

Along with the fencing, the BSF has built a new road not meant for civilians but frequented by Lejri and Lahalein residents during emer gencies. Unfortunately , the border road passes over a river, which only has a footbridge, so transporting heavy goods to and from Umkiang market isn't viable. To bypass the border fence and continue selling their goods to Bangladeshi businessmen, desperate villagers have begun wading into treacherous rivers. A few have drowned mid-stream. The fencing has also restricted villagers' access to their own fields. In 2015, Lejri's Brave Sumer slipped across the border to collect betel nuts from a field he'd cultivated before it was demarcated as no man's land. He was apprehended by Bangladeshi border guards, brutally beaten up, and imprisoned for 1.5 years. “I thought my life was over,“ he says.

“If the government doesn't want to fix the road, it should remove the fencing and give us to Bangladesh,“ says Lahalein's Lamsingh Tynsong. It's a popular sentiment in a region where development is stunted because there's no road to transport new infrastructure. Just a few months ago, Huroi got solar power systems from the government but no vehicle could fit the 60 lampposts allotted to the village. So, 240 residents four per lamppost carried them from Prang River to Huroi, which took over three hours.

The matter reached the Prime Minister's office last year when two college students, Kynjaimon Amse and Raja Suchen, penned a letter detailing the lack of facilities. “We live and survive upon the mercy of the Bangladeshi people,“ they wrote. Amse, a law student, and Suchen, a Huroi native, followed this up with letters to the National Human Rights Commission and the then Meghalaya Governor Banwarilal Purohit. The governor responded by criticising the state's “shameful inability“ to take care of its citizens and asking for an investigation into the Bangladeshi trade because it infringes on India's sovereignty .

In places where the border fence is still under construction, Bangladeshis cross through the jungle and hawk their wares door-to-door accepting takas in exchange. Representatives of all four villages feigned ignorance about this when they met Maham Singh Lhuid, the district's deputy commissioner, in March this year. They were justifiably terrified that the government would increase security at the border without bothering to repair the road, trapping them in between.

During our visit, wary village councils banished Bangladeshi traders and held meetings to decide how much to reveal. The first person to speak openly was a village secretary , whose frustration peaked after his 11-month-old nephew paid the price for government apathy . The infant, who had a recurring illness, deteriorated suddenly and was rushed to a Bangladeshi hospital.There, doctors refused to treat him because he was Indian. He died the night we arrived.

Politicians visit Huroi with tall claims of being “road doctors“. Then they disappear for the next five years. In protest, Huroi residents have decided to boycott the 2018 elections to the state legislative assembly . However, Lhuid, the district's deputy commissioner, is hoping to pacify them by improving Huroi's subhealth centre and setting up a mobile tower before the election.

But for people like 67-year-old Lokhi Suting nothing is more important than the road. She's lost four children, a grandchild and a husband because she refused to take them to Bangladesh for treatment. “I was always too scared to break the law,“ she says. Losing her children three in quick succession drove her insane with grief.She still cries for them at night for her six-yearold boy , for her newborn baby , for the eldest who was 18 and for her son named `India'.

Garo hills

2015: HC directs AFSPA imposition

The Times of India, Nov 05 2015

Manosh Das

Meghalaya HC asks Centre to impose AFSPA in Garo Hills

The Meghalaya high court's directive on Monday asking the Centre to consider imposing the controversial Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, 1958, in insurgency-ravaged Garo Hills has hit the state where it hurts most. The move comes amidst prolonged movements for the repeal of the act from the northeast which have rocked the region's states, especially Manipur, over the years.

The high court cited rising cases of kidnappings and killings by militant groups in the Garo Hills in its order.

“Recently , a central intelligence officer and a trader who had been kidnapped for ransom were killed by insurgents. According to data supplied by Meghalaya Police, Garo insurgents abducted 25 civilians, 27 businessmen, 25 private sector employees, five government employees and five teachers between January and October 31 this year,“ a police officer said.

“This court... cannot remain a mute spectator and shy away from its constitutional obligation to protect the fundamental rights guaranteed by Part III of the Constitution in general and Article 21 in particular,“ the full bench of the Meghalaya HC observed in its ruling. The HC directed the Union home secretary and defence secretary to ensure compliance by placing the order before the Centre.

The Scheduled Tribes Census of India 2001

Meghalaya is predominantly a tribal state. The popula tion of Meghalaya at 2001 Census has been 2,318,822. Of these 1,992,862 persons are Scheduled Tribes (STs), which constitute 85.9 per cent of the state’s total popul ation. The state has registered 31.3 per cent decadal growth of ST population in 1991 -2001. There are total seventeen (17) notified STs in the state, and all of them have been enumerated in 2001 Census.

Population: Size & Distribution

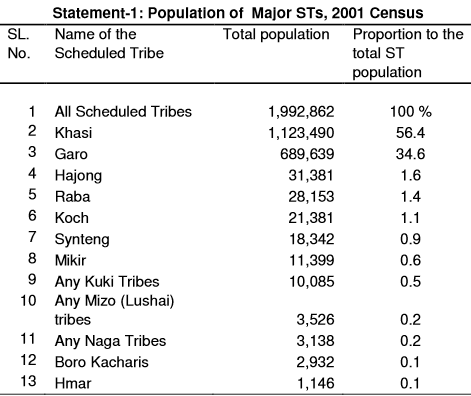

2.Individual ST wise, Khasi constitute more than half of the total ST population of the state (56.4 per cent). Garo is second with 34.6 per cent. They together constitute 91 per cent of the total ST population. Synteng is listed both as a sub-tribe under Khasi and also as a separate ST. In 2001 Census, 18,342 population of Synteng has been enumerated separately, which constitute 0.9 per cent of total STs. The Hajong (1.6 per cent), Raba (1.4 per cent), and Koch (1.1 per cent) have sizable population in the state, each representing above one per cent of the state’s tot al ST population. The rest of the STs are very small in their population size. Of these, five STs namely Man (Tai speaking), Dimasa, Chakma, Pawi, and Lakher are having population between 617 to 10 only (Statement-1).

3.The STs in Meghalaya are predominantly rural (84.4 per cent). Individual ST wise, Koch are overwhelmingly confined to rural areas ( 97.2 per cent), followed by Raba (92.6 per cent), Hajong (91.4 per cent), and Garo (88.7 per cent). On the contrary, higher urban population has been registered among Synteng ( 28.2 per cent) and Khasi (18.6 per cent).

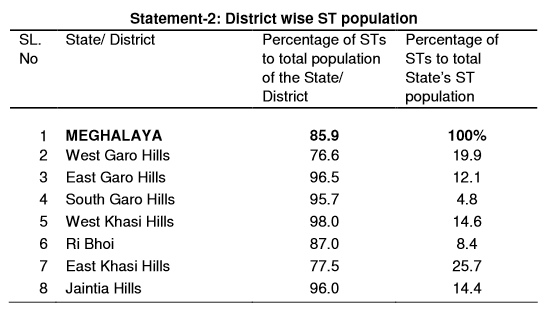

4.Of the seven districts of Meghalaya, in four the ST p opulation constitutes more than 95 per cent. East Khasi Hills has recorded the lowest at 77.5 per cent. This district, however, shares the highest 25.7 per cent of the total ST population of the state, Statement-2.

Sex Ratio

5.The matrilineal Meghalaya has recorded an even distribution of male and female population. Of the total ST population 996,5 67 have been returned as males and 996,295 as females. Individual ST wise, Synteng (1024) and Khasi (1017) have recorded sex ratio higher than 1000 mark. Although Garo have r ecorded comparatively low sex ratio (979) in the state, their sex ratio, however, is better than the aggregated national average for STs (978).

6.The child sex ratio (0-6 age group) of 974 for STs in the state is higher than the national average (973) for the corresponding populati on. Hajong (1003), Synteng (980), and Khasi (979) have registered child sex ratio above the state average (974). Quite contrary to the overall situation in the state, the c hild sex ratio is low among Raba (923). Literacy & Educational Level

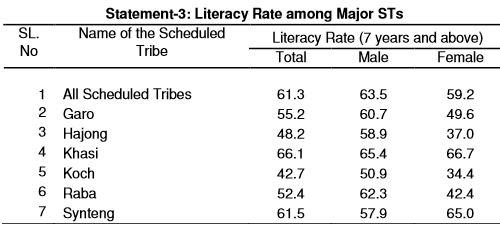

7.The literacy rate among the STs in Meghalaya is 61.3 per cent, which is above the national average for STs (47.1 per cent). With 635 per cent male and 59.2 per cent female literacy rate, the ST women in the state are q uite at per with their male counterparts.

8.Khasi have registered the highest 66.1 per cent literacy rate among the six major STs in the state. Literacy rate is the lowest among Koch (42.7 per cent), closely followed by Hajong (48.2 per cent). It is significant t hat among Khasi and Synteng, the females are better off in literacy status. On the cont rary with 58.9 per cent male and 37 per cent female literacy, the Hajong women are lagging behind by as much as 22 per cent points. Significant gender gap in literacy has also been recorded among Raba, Koch, and Garo, Statement-3.

9.Merely 54.9 per cent of the ST population in the a ge group 5-14 years – the category of potential students – has been attending schools or any other educational institutions. Khasi have registered the highest 61.5 per cent, closely followed by Synteng (55.3 per cent) and Hajong (50.7 per cent). On the o ther hand Koch have recorded the lowest at 44.3 per cent. Less than half of the populati on among Garo (45 per cent) and Raba (47.8 per cent) are attending schools in this age group. 10.Of the total ST literates, 3.3 per cent are having educational level graduate and above. Synteng (4.6 per cent) and Khasi (4.4 per cent) are well ahead, among the six major STs in the state, with more than four per cent o f their literate population having this educational status. Rabha, Koch, and Hajong are compara tively lagging behind with one per cent of their literates having this level of educa tion.

Work Participation Rate (WPR)

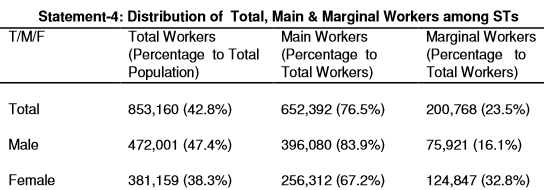

11.In 2001 Census, 42.8 per cent of the ST population has been recorded as workers, which is below the aggregated national figure for STs (49.1 per cent). Of the total workers 76.5 per cent have been recorded as main workers and 23.5 per cent as marginal workers. WPR at 38.3 per cent among female is lower than male (47.4 per cent). In Meghalaya, the ST women are rather close to their male counterparts with 83.9 per cent male and 67.2 per cent female as main workers, Statement-4.

12.With regards to WPR there is not much variation am ong the different STs. The highest WPR of 46.5 per cent has been registered among Raba, while it is the lowest among Synteng (41.7 per cent). The Khasi and Hajong b oth have an identical WPR at 41.8 per cent. The gender gap in work participation is quite significant among Hajong (male 50.1 per cent, female 33.3 per cent) and Koch (m ale 52.5 per cent, female 37.5 per cent), while it is the lowest among Garo (male 47.7 per cent, female 40.2 per cent).

Category of Workers

13.Of the total ST main workers, 56.2 per cent have been registered as cultivators and another 13.1 per cent as agricultural labourers. 289 per cent have been returned as ‘other workers’ and the remaining 1.8 per cent in the household industry category.

14.The highest 70.7 per cent cultivators have been reco rded among Raba, followed by Garo (67.4 per cent), Khasi (49.5 per cent), and Koch (49.2 per cent). On the other hand the percentage of cultivators is the lowest among Hajong (35.5 per cent). A substantial number of Hajong main workers have, however, been recorded as agricultural labourers (18.8 per cent). Koch have recorded the highe st 21.5 per cent agricultural labourers as main workers.

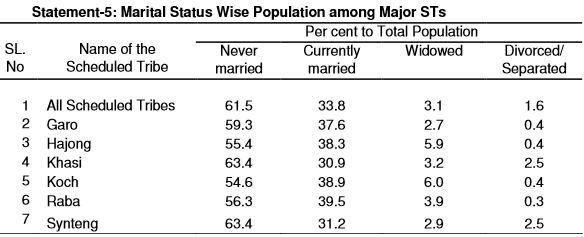

Marital Status

15.As regards marital status, 61.5 per cent of the popul ation is never married, 33.8 per cent currently married, 3.1 per cent widowed, and merely 1.6 per cent divorced /separated. It is significant to note a very high of 2. 5 per cent population among Khasi and Synteng has been recorded as divorced/separated (St atement-5).

16.Merely 1.5 per cent of the ST female population b elow 18 years – the minimum legal age for marriage – has been recorded as ever mar ried. Of the six major STs, the Synteng has recorded the highest at 1.8 per cent, whi le Khasi the lowest at 1.4 per cent.

17.The ever married males below 21 years – the minimu m legal age for marriage – constitute only 1.3 per cent of the total ST populat ion of this age category. The Synteng has recorded the highest at 1.5 per cent among the six major STs, while it is the lowest (1.1 Per cent) among Hajong.

Religion

18.Of the total ST population majority 79.8 per cent are Christians and 5.9 per cent Hindus. A substantial number of ST population (13. 2 Per cent) have been recorded under “Other religions and persuasions”. Quite a large number (6,324 persons) did not mention their faith, and they have been categorized under “Religion not stated”. Besides, 13,105 persons have been recorded as Muslims and 2,249 as Buddhists constituting 0.7 per cent and 0.1 per cent respectively.

Mines

Illegal coal mining/ 2018

An ‘underground economy’ has for long been known to fuel Meghalaya’s politics. It has taken the collapse of a coal mine and – in all probability – the death of at least 15 miners for the reality of illegal mining to hit hard.

The accident on December 13, when the miners struck an aquifer leading to the flooding of a 370-foot mine, was the first after the National Green Tribunal (NGT) banned unscientific ‘rat-hole mining’ in the State on April 17, 2014.

Where is the mine?

The mine, about 130 km from the capital Shillong, is at Ksan near the river Lytein in the Saipung area of East Jaintia Hills, one of eight mining districts of the State.

The site is 48 km from where rights and anti-mining activist Agnes Kharshiing was assaulted a month ago for her campaign against illegal mining. East Jaintia Hills has a major share of an estimated coal reserve of 576 million tonnes in the State, which also has substantial deposits of limestone and other minerals. Much of the coal sent out of Meghalaya before the NGT ban was from this district. An assessment by a committee, constituted by the NGT, recorded the highest amount of extracted coal — 3.7 million tonnes of a total 6.5 million tonnes — in the State in September 2014.

What prompted the NGT ban?

The NGT ban, retained in 2015, followed a petition filed by the All Dimasa Students’ Union in Assam. The union had cited a study by O.P. Singh of the North Eastern Hill University that said mining in the coal belts and coal stockpiles in the Jaintia Hills areas were polluting rivers and streams flowing down to Assam’s Dima Hasao district, killing aquatic life and rendering the water unfit for drinking or irrigation. Apart from the ecological impact, the NGT observed that “there is umpteen number of cases where by virtue of rat-hole mining, during the rainy season, water flooded into the mining areas resulting in the death of many.” The trigger for the ban was the case of 15 miners trapped fatally inside a flooded mine in the South Garo Hills in July 2012. In between, a Shillong-based NGO filed a public interest litigation petition against illegal coal mining, claiming the rat-hole mines employed 70,000 child labourers. The government later said only 222 children were found working in the mines.

What is rat-hole mining?

Coal mining in Meghalaya, financed by businessmen from outside, took off commercially in the 1980s. Since much of the State’s land is community-owned, it was easy for the moneyed locals to purchase land and employ non-tribal labourers to burrow for maximum profit. Rat-hole mining, involving digging of tunnels 3-4 feet high, was the most preferred to strike at narrow coal seams deeper inside the hills.

The less dangerous of two methods of digging tunnels is side-cutting on the slopes. The other method entails digging a rectangular pit vertically to a depth of up to 400 metres. Rat-hole-sized tunnels are dug horizontally wherever the coal seams are found for the workers to crawl in and out. The NGT found these techniques unscientific and unsafe for workers.

Why does it continue?

Many who matter in Meghalaya own a coal mine or are associated with the trade. They include politicians, bureaucrats, police officers and extremists. In 2015, the State government said the ban would cost it ₹600 crore in revenue. The high stakes involved had made political parties promise reopen coal mines during the February Assembly election.

Chief Minister Conrad Sangma, earlier in denial mode, has admitted after the accident that illegal mining does happen. He has promised appropriate action but at the same time said mining activities are spread across too vast an area to monitor.

Activists are sceptical; on Thursday, an affidavit in the Meghalaya High Court pointed out that the prime accused in the mob attack on Ms. Kharshiing and her associate Amita Sangma was a leader of the ruling National People’s Party and there was no hope of a “meaningful investigation” because of a nexus among the coal mafia, the police and politicians.

Wildlife parks and sanctuaries: India

LIVING ADVENTUROUSLY

HANG GLIDING/PARA GLIDING

Picturesque Shillong in Meghalaya with its beautiful landscapes is an ideal ground for aero sports, particularly gliding (hang/para gliding).

TREKS

There has been an increased interest in the many caves located in Meghalaya. There are said to as many as 200 caves which are yet to be mapped or explored. The surveyed caves include five which are the largest in the Indian subcontinent. Major caves are located in the Khasi hills, Jantia hills, South Garo hills.