Mewar 08: Historical facts furnished by the bard Chand

This page is an extract from OR THE CENTRAL AND WESTERN By Edited with an Introduction and Notes by In Three Volumes HUMPHREY MILFORD |

Note: This article is likely to contain several spelling mistakes that occurred during scanning. If these errors are reported as messages to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com your help will be gratefully acknowledged.

Mewar 08: Historical facts furnished by the bard Chand

Samar Singh, Samarsi

Although the whole of this chain of ancestry, from Kanaksen in the second, Vijaya the founder of Valabhi in the fourth, to Samarsi in the thirteenth century, cannot be discriminated with perfect accuracy, we may affirm, to borrow a metaphor, that " the two extremities of it are riveted in truth " : and some links have at intervals been recognized as equally valid. We will now extend the chain to the nineteenth century.

The Tuars of Delhi

Samarsi was born in S. 1206.1 Though the domestic annals are not silent on his acts, we shall recur chiefly to the bard of Delhi - for his char 2 [For the error in his date see p. 281 above.] " The work of Chand is a universal history of the period in which he wrote. In the sixty-nine books, comprising one hundred thousand stanzas, relating to the exploits of Prithiraj, every noble family of Rajasthan will find some record of their ancestors. It is accordingly treasured amongst the archives of each race having any pretensions to the name of Rajput. acter and actions, and the history of the period. Before we pro ceed, however, a sketch of the pohtical condition of Hindustan during the last of the Tuar sovereigns of Delhi, derived from this authority and in the bard's own words, may not be unacceptable. " In Patan is Bhola Bhim the Chalukya, of iron frame.1 On the mountain Abu, Jeth Pramara, in battle immovable as the star of the north. In Mewar is Samar Singh, who takes tribute from the mighty, a wave of iron in the path of Delhi's foe. In the midst of all, strong in his own strength, Mandor's prince, the arrogant Nahar Rao, the might of Maru, fearing none. In Delhi the chief of all [255] Ananga, at whose summons attended the princes of Mandor, Nagor, Sind, Jalwat,2 and others on its confines, Peshawar, Lahore, Kangra, and its mountain chiefs, with Kasi,3 Prayag,4 and Garh Deogir. The lords of Simar 5 were in constant danger of his power." The Bhatti, since their expulsion from Zabulistan, had successively occupied as capitals, Salivahanapur in the Panjab, Tanot, Derawar, which last they founded, and the ancient Lodorwa, which they conquered in the desert ; and at the period in question were constructing their present residence, Jaisalmer. In this nook they had been fighting for centuries

From this he can trace his martial forefathers who ' drank of the wave of battle ' in the passes of Kirman when the ' cloud of war rolled from Himachal to the plains of Hindustan. The wars of Prithiraj, his alliances, his numerous and powerful tributaries, their abodes and pedigrees, make the works of Chand invaluable as historic and geographical memoranda, besides being treasures in mythology, manners, and the annals of the mind. To read this poet well is a sure road to honour, and my own Guru was allowed, even by the professional bards, to excel therein. As he read I rapidly translated about thirty thousand stanzas. Familiar with the dialects in which it is written, I have fancied that I seized occasionally the poet's spirit ; but it were presumption to suppose that I embodied all his brilliancy, or fully comprehended the depth of his allusions. But I knew for whom he wrote. The most familiar of his images and sentiments I heard daily from the mouths of those around me, the descendants of the men whoso deeds he rehearses. I was enabled thus to seize his meaning, where one more skilled in poetic lore might have failed, and to make my prosaic version of some value. [For Chand Bardai see Grierson, Modern Literary History of Hiildustan, 3 f.]

1 [Bhima II., Chaulukya, known as Bhola, 'the simpleton,' a.d. 1179 1242.] 2 Unknown, unless the country on the ' waters ' {jal) of Sind. 3 Benares. 4 Allahabad. 5 The cold regions {ai, ' cold '). with the heutenants of the Cahph at Aror, occasionally redeeming their ancient possessions as far as the city of the Tak on the Indus. Their situation gave them little political interest in the affairs of Hindustan until the period of Prithiraj, one of whose principal leaders, Achales, was the brother of the Bhatti prince. Anangpal, from this description, was justly entitled to be termed the para mount sovereign of Hindustan ; but he was the last of a dynasty of nineteen princes, who had occupied Delhi nearly four hvmdred years, from the time of the founder Bilan Deo, who, according to a manuscript in th.e author's possession, was only an opulent Thakur when he assumed the ensigns of royalty in the then deserted Indraprastha, taking the name of Anangpal,^ ever after titular in the family. The Cliaulians of Ajmer owed at least homage to Delhi at this time, although Bisaldeo had rendered it almost nominal ; and to Someswar, the fourth in descent, Anang pal was indebted for the preservation of this supremacy against the attempts of Kanauj, for which service he obtained the Tuar's daughter in marriage, the issue of which was Prithiraj, who when only eight yeai's of age was proclaimed successor to the Delhi throne.

Prithiraj

Jaichand of Kanauj and Prithiraj bore the same relative situation to Anangpal ; Bijaipal, the father of the former, as well as Someswar, having had a daughter of the Tuar to wife. This originated the rivalry between the Chauhans and Rathors which ended in the destruction of both. When Prithiraj mounted the throne of Delhi, Jaichand not only refused to acknowledge his supremacy, but set forth his own claims to this distinction. In these he was supported by the prince of Patau [256] Aiihil wara (the eternal foe of the Chauhans), and likewise by the Pari hars of ISIandor. But the affront given by the latter, in refusing to fulfil the contract of bestowing his daughter on the young Chauhan, brought on a warfare, in which this first essay was but the presage of his future fame. Kanauj and Patan had recourse to the dangerous expedient of entertaining bands of Tatars, through whom the sovereign of Ghazni was enabled to take advantage of their internal broils.

1 Ananga is a poetical epithet of the Hindu Cupid, literally ' incorporeal ' ; but, according to good authority, apphcable to the founder of the desolate abode, palna being ' to support,' and anga, with the primitive an, ' without body.' Samarsi, prince of Chitor, had married the sister of Prithiraj, and their personal characters, as well as this tie, bound them to each other throughout all these commotions, until the last fatal battle on the Ghaggar. From these feuds Hindustan never was free. But unrelenting enmity was not a part of their character : having displayed the valour of the tribe, the bard or Nestor of the day would step in, and a marriage would conciliate and main tain in friendship such foes for two generations. From time immemorial such has been the political state of India, as repre sented by their own epics, or in Arabian or Persian histories : thus always the prey of foreigners, and destined to remain so. Samarsi had to contend both with the princes of Patau and Kanauj ; and although the bard says " he washed his blade in the Jumna," the domestic annals slur over the circumstance of Siddharaja-Jayasingha having actually made a conquest of Chitor ; for it is not only included in the eighteen capitals enumer ated as appertaining to this prince, but the author discovered a tablet 1 in Chitor, placed there by his successor, Kumarpal, bear ing the date S. 1206, the period of Samarsi's birth. The first occasion of Samarsi's aid being called in by the Chauhan emperor was on the discovery of treasure at Nagor, amounting to seven millions of gold, the deposit of ancient days. The princes of Kanauj and Patan, dreading the influence which such sinews of war would afford their antagonist, invited Shihabu-d-din to aid their designs of humiliating the Chauhan, who in this emergency sent an embassy to Samarsi. The envoy was Chand Pundir, the vassal chief of Lahore, and guardian of that frontier. He is con spicuous from this time to the hour " when he planted his lance at the ford of the Ravi," and fell in opposing the passage of Shihabu d-din. The presents he carries, the speech with which he greets the Chitor prince, his reception, reply, and dismissal are all pre served by [257] Chand. The style of address and the apparel of Samarsi betoken that he had not laid aside the office and ensigns of a ' Regent of Mahadeva.' A simple necklace of the seeds of the lotus adorned his neck ; his hair was braided, and he is addressed as Jogindra, or chief of ascetics. Samarsi proceeded to Delhi ; and it was arranged, as he was connected by marriage with the prince of Patan, that Prithiraj should march against this prince, while he should oppose the army from Ghazni. He 1 See luscriptiou No. 5. (Samarsi) accordingly fought several indecisive battles, which gave time to the Chauhan to terminate the war in Gujarat and rejoin him. United, they completely discomfited the invaders, making their leader prisoner. Samarsi declined any share of the dis covered treasure, but permitted his chiefs to accept the gifts offered by Chauhan. Many years elapsed in such subordinate warfare, when the prince of Chitor was again constrained to use his buckler in defence of Delhi and its prince, whose arrogance and successful ambition, followed by disgraceful inactivity, in vited invasion with every presage of success. Jealousy and revenge rendered the princes of Patan, Kanauj, Dhar, and the minor courts indifferent spectators of a contest destined to over throw them all.

The Death of Samar Singh

The bard gives a good description of the preparations for his departure from Chitor, which he was destined never to see again. The charge of the city was entrusted to a favourite and younger son, Kama : which disgusted the elder brother, who went to the Deccan to Bidar, where he was well received by an Abyssinian chief,1 who had there established himself in sovereignty. Another son, either on this occasion or on the subsequent fall of Chitor, fled to the mountains of Nepal, and there spread the Guhilot line.2 It is in this, the last of the books of Chand, termed The Great Fight, that we have the char acter of Samarsi fully delineated. His arrival at Delhi is hailed with songs of joy as a day of deliverance. Prithiraj and his court advance seven miles to meet him, and the description of the greeting of the king of Delhi and his sister, and the chiefs on either side who recognize ancient friendships, is most animated. Sam arsi reads his brother-in-law an indignant lecture on his unprincely inactivity, and throughout the book divides attention with him.

In the planning of the campaign, and march towards the Ghaggar to meet the foe [258], Samarsi is consulted, and his opinions are recorded. The bard represents him as the Ulysses of the host : brave, cool, and skilful in the fight ; prudent, wise, and eloquent in council ; pious and decorous on all occasions ; beloved by his own chiefs, and reverenced by the vassals of the Chauhan. In the line of march no augur or bard could better

1 Styled Habshi Padshah. 2 [The Gorkhas or Gurkhas are said to have reached Nepal through Kumaun after the fall of Chitor {IGI, xix. 32).] explain the omens, none in the field better dress the squadrons for battle, none guide his steed or use his lance with more address. His tent is the principal resort of the leaders after the march or in the intervals of battle, who were delighted by his eloquence or instructed by his knowledge. The bard confesses that his precepts of government are chiefly from the lips of Khuman ; 1 and of his best episodes and allegories, whether on morals, rules for the guidance of ambassadors, choice of ministers, religious or social duties (but especially those of the Rajput to the sovereign), the wise prince of Chitor is the general organ.

On the last of three days' desperate fighting Samarsi was slain, together with his son Kalyan, and thirteen thousand of his house hold troops and most renowned chieftains.2 His beloved Pirtha, on hearing the fatal issue, her husband slain, her brother captive, the heroes of Delhi and Chitor " asleep on the banks of the Ghaggar, in the wave of the steel," joined her lord through the flame, nor waited the advance of the Tatar king, when Delhi was carried by storm, and the last stay of the Chauhans, Prince Rainsi, met death in the assault. The capture of Delhi and its monarch, the death of his ally of Chitor, with the bravest and best of their troops, speedily ensured the further and final success of the Tatar arms ; and when Kanauj fell, and the traitor to his nation met his fate in the waves of the Ganges, none were left to contend with Shihabu-d-din the possession of the regal seat of the Chauhan. Scenes of devastation, plunder, and massacre commenced, which lasted through ages ; during which nearly all that was sacred in religion or celebrated in art was destroyed by these ruthless and barbarous invaders. The noble Rajput, with a spirit of constancy and enduring courage, seized every opportunity to turn upon his oppressor. By his perseverance and valour he wore out entire dynasties of foes, alternately yielding ' to his fate,' or restricting the circle of conquest. Every road in Rajasthan was moistened with torrents of blood of the [259] spoiled and the spoiler. But all was of no avail ; fresh supplies were ever pouring in, and dynasty succeeded dynasty, heir to the same remorseless feeling which sanctified murder, legalized spoliation, and deified destruc

1 I have already mentioned that Khuman became a patronymic and title amongst the princes of Chitor. 2 [The battle was fought at Tarain or Talawari in the Ambala District, Panjab, in 1192.] tion. In these desperate conflicts entire tribes were swept away whose names are the only memento of their former existence and celebrity.

Gallant Resistance of the Rajputs

What nation on earth would have maintained the semblance of civilization, the spirit or the customs of their forefathers, during so many centuries of overwhelming depression but one of such singular character as the Rajput ? Though ardent and reckless, he can, when required, subside into forbearance and apparent apathy, and reserve himself for the opportunity of revenge. Rajasthan exhibits the sole example in the history of mankind of a people withstanding every outrage barbarity can inflict, or human nature sustain, from a foe whose religion commands annihilation, and bent to the earth, yet rising buoyant from the pressure, and making calamity a whetstone to courage. How did the Britons at once sink under the Romans, and in vain strive to save their groves, their druids, or the altars of Bal from destruction ! To the Saxons they alike succumbed ; they, again, to the Danes ; and this heterogeneous breed to the Normans. Empire was lost and gained by a single battle, and the laws and religion of the conquered merged in those of the conquerors. Contrast with these the Rajputs ; not an iota of their religion or customs have they lost, though many a foot of land. Some of their States have been expunged from the map of dominion ; and, as a punishment of national infidelity, the pride of the Rathor, and the glory of the Chalukya, the overgrown Kanauj and gorgeous Anhilwara, are forgotten names ! Mewar alone, the sacred bulwark of religion, never compromised her honour for her safety, and still survives her ancient limits ; and since the brave Samarsi gave up his life, the blood of her princes has flowed in copious streams for the maintenance of this honour, religion, and independence.

Karan Singh I. : Ratan Singh

Samarsi had several sons ; 1 but Kama was his heir, and during his minority his mother, Kuram devi, a princess of Patau, nobly maintained what his father left. She headed her Rajputs and gave battle 2 in person to Kutbu-d-din, 3 Kalyanrae, slain with his father; Kumbhkaran, who went to Bidar; a third, the founder of the Gorkhas. [This assertion, based on the authority of Chand, is incorrect, Samar Singh being misplaced, and succeeded by Ratan Singh (Erskine ii. A. 146).] 2 This must be the battle mentioned by Ferishta (see Dow, p. 169, vol. ii.). near [260] Amber, when the viceroy was defeated and wounded . Nine Rajas, and eleven chiefs of inferior dignity with the title of Rawat, followed the mother of their prince.

Kama (the radiant) succeeded in S. 1249 (a.d. 1193) ; but he was not destined to be the founder of a line in Mewar.1 The annals are at variance with each other on an event which gave the sovereignty of Chitor to a younger branch, and sent the elder into the inhospitable wilds of the west, to found a city - and per petuate a line.2 It is stated generally that Kama had two sons, Mahup and Rahup ; but this is an error : Samarsi and Surajmall were brothers : Kama was the son of the former and Mahup was his son, whose mother was a Chauhan of Bagar. Surajmall had a son named Bharat, who was driven from Chitor by a conspiracy. He proceeded to Sind, obtained Aror from its prince, a Musalman, and married the daughter of the Bhatti chief of Pugal, by whom he had a son named Rahup. Kama died of grief for the loss of Bharat and the unworthiness of Mahup, who abandoned him to live entirely with his maternal relations, the Chauhans.

The Sonigira chief of Jalor had married the daughter of Kama, 1 He had a son, Sarwan, who took to commerce. Hence the mercantile Sesodia caste, Sarwania. 2 Dungarpur, so named from dungar, ' a mountain.' 3 [The facts are tliat after " Karan Singh the Mewar family divided into one with the title of Rawal, the other Rana. In the first, or Rawal, branch were Khem or Kshem Singh, the eldest son of Karan Singh, Samant Singh, Kumar Singh, Mathan Singh, Padam Singh, Jeth Singh, Tej Singh, Samar Singh, and Ratan Singh, all of whom reigned at Chitor ; while in the Rana branch were Rahup, a younger son of Karan Singh, Narpat, Dinkaran, Jaskaran,Nagpal, Puranpal, PrithiPal, Bhuvan Singh, Bhim Singh, Jai Singh, and Lakshman Singh, who ruled at Sesoda, and called themselves Sesodias. Thus, instead of having to fit in something like ten generations between Samar Singh, who, as we know, was ahve in 1299, and the siege of Chitor, which certainly took place in 1303, we fijid that those ten princes were not descendants of Samar Singh at all, but the contemporaries of his seven immediate predecessors on the gaddi of Chitor and of himself, and that both Ratan Singh, the son of Samar Singh, and Lakshman Singh, the contemporary of Ratan Singh, were descended from a common ancestor, Karan Singh I., nine and eleven generations back respectively. It is also possible to reconcile the statement of the Musalman historians that Ratan singh (called Rai Ratan ) was ruler of chitor during the siege-- a statement corroborated by an inscription at Rajnagar—

with the generally accepted story that it was Rana Lakshman Singh who fell in defence of the fort " (Erskine ii. A. 15).] by whom he had a child named Randhol, 1 whom by treachery he placed on the throne of Chitor, slaying the chief Guhilots. Mahup being unable to recover his rights, and unwilling to make any exertion, the chair of Bappa Rawal would have passed to the Chauhans but for an ancient bard of the house. He pursued his way to Aror, held by old Bharat as a fief of Kabul. With the levies of Sind he marched to claim the right abandoned by Mahup and at Pali encountered and defeated the Sonigiras. The re tainers of Mewar flocked to his standard, and by their aid he enthroned himself in Chitor. He sent for his father and mother, Ranangdevi, whose dwelling on the Indus was made over to a younger brother, who bartered his faith for Aror, and held it as a vassal of Kabul.

Rahup

Rahup obtained Chitor in S. 1257 (a.d. 1201), and shortly after sustained the attack of Shamsu-d-din, whom he met and overcame in a battle at Nagor. Two [261] great changes were introduced by this prince ; the first in the title of the tribe, to Sesodia ; the other in that of its prince, from Rawal to Rana. The puerile reason for the former has already been noticed ; 2 the cause of the latter is deserving of more attention. Amongst the foes of Rahup was the Parihar prince of Mandor : his name Mokal, with the title of Rana. Rahup seized him in his capital and brought him to Sesoda, making him renounce the rich district of Godwar and his title of Rana, which he assumed himself, to denote the completion of his feud. He ruled thirty-eight years in a period of great distraction, and appears to have been well calculated, not only to uphold the fallen fortunes of the State, but to rescue them from utter ruin. His reign is the more re markable by contrast with his successors, nine of whom are ' pushed from their stools ' in the same or even a shorter period than that during which he upheld the dignity.

From Rahup to Lakhamsi [Lakshman Singh], in the short space of half a century, nine princes of Chitor were crowned, and at nearly equal intervals of time followed each other to ' the mansions of the sun.' Of these nine, six fell in battle. Nor did they meet their fate at home, but in a chivalrous enterprise to redeem the sacred Gaya from the pollution of the barbarian.

1 So pronounced, but properly written Randhaval, ' the standard of the field.' 2 See note, p. 252. VOL. I X For this object these princes successively fell, but such devotion inspired fear, if not pity or conviction, and the bigot renounced the impiety which Prithunall purchased with his blood, and until Alau-d-din's reign, this outrage to their prejudices was renounced. But in this interval they had lost their capital, for it is stated as the only occurrence in Bhonsi's ^ reign that he [262] " recovered Chitor " and made the name of Rana be acknowledged by all. Two memorials are preserved of the nine princes from Rahup to Lakhamsi, and of the same character : confusion and strife within and without. We will, therefore, pass over these to another grand event in the vicissitudes of this house, which possesses more of romance than of history, though the facts are undoubted.

1 His second son, Chandra, obtained an appanage on the Charabal, and his issue, well known as Chandarawats, constituted one of the most powerful vassal clans of Mewar. Rampura (Bhanpura) was their residence, yielding a revenue of nine lakhs (£110,000), held on the tenure of service which, from an original grant in my possession from Rana Jagat Singh to his nephew Madho Singh, afterwards prince of Amber, was three thousand horse and foot (see p. 235), and the fine of investiture was seventy-five thousand rupees. Madho Singh, when prince of Amber, did what was invahd as well as un grateful ; he made over this domain, granted during his misfortunes, to Holkar, the first limb lopped off Mewar. The Chandarawat proprietor con tinued, however, to possess a portion of the original estate with the fortress of Amad, which it maintained throughout all the troubles of Rajwara till A.D. 1821. It shows the attachment to custom that the young Rao apphed and received ' the sword ' of investiture from his old lord paramount, the Rana, though dependent on Holkar's forbearance. But a minority is pro verbially dangerous in India. Disorder from party plots made Amad troublesome to Holkar's government, which as his ally and preserver of tranquillity we suppressed by blowing up the walls of the fortress. This is one of many instances of the harsh, uncompromising nature of our power, and the anomalous description of our alhances with the Rajputs. However necessary to repress the disorder arising from the claims of ancient pro prietors and the recent rights of Holkar, or the new proprietor, Ghafur Khan, yet surrounding princes, and the general population, Mdio know the history of past times, lament to see a name of five hundred years' duration thus summarily extinguished, which chiefly benefits an upstart Pathan. Such the vortex of the ambiguous, irregular, and unsystematic policy, which marks many of our alhances, which protect too often but to injure, and gives to our office of general arbitrator and high constable of Rajasthan a harsh and unfeeHng character. Much of this arises from ignorance of the past history ; much from disregard of the peculiar usages of the people ; or from that expediency which too often comes in contact with moral fitness, which will go on until tlic day predicted by the Nestor of India, when " one sikha (seal) alone will be used in Hindustan."

Lakhamsi : Lachhman Singh

Lakhamsi 1 succeeded his father in S. 1331 (a.d. 1275), a memorable era in the annals, when Chitor, the repository of all that was precious yet untouched of the arts of India, was stormed, sacked, and treated with remorseless barbarity by the Pathan [Khilji] emperor, Alau-d-din. Twice it was attacked by this subjugator of India. In the first siege it escaped spoliation, though at the price of its best defenders : that which followed is the first successful assault and capture of which we have any detailed account.

Bhim Singh : Padmini

Bhimsi was the uncle of the young prince, and protector during his minority. He had espoused the daughter of Hamir Sank (Chauhan) of Ceylon, the cause of woes unnumbered to the Sesodias. Her name was Padmini, 2 a title bestowed only on the superlatively fair, and transmitted with renown to posterity by tradition and the song of the bard. Her beauty, accomplishments, exaltation, and destruction, with other incidental circumstances, constitute the subject of one of the most popular traditions of Rajwara. The Hindu bard recognizes the fair, in preference to fame and love of conquest, as the motive for the attack of Alau-d-din, who [263] limited his demand to the possession of Padmini ; though this was after a long and fruitless siege. At length he restricted his desire to a mere sight of this extraordinary beauty, and acceded to the proposal of beholding her through the medium of mirrors. Relying on the faith of the Rajput, he 'entered Chitor slightly guarded, and having gratified his wish, returned. The Rajput, unwilling to be outdone in con fidence, accompanied the king to the foot of the fortress, amidst many complimentary excuses from his guest at the trouble he thus occasioned. It was for this that Ala risked his own safety, relying on the superior faith of the Hindu. Here he had an

1 [Rana Lachhman Singh was not, strictly speaking, ruler of Chitor. He belonged to the Rana branch, and succeeded Jai Singh. When Chitor was invested he came to lielp his relation, Rawal Ratan Singh, husband of Padmini, and ruler of Chitor, and was killed, with seven of his sons (Erskine ii. B. 10).] 2 [' The Lotus.' Ferishta in his account of the siege aaya nothing of Padmini (i. 353 f.). Her story is told in Ain, ii. 269 f.]{j ambush ; Bhimsi was made prisoner, hurried away to the Tatar camp, and his hberty made dependent on the surrender of Padmini.

The Siege of Chitor

Despair reigned in Chitor when this fatal event was known, and it was debated whether Padmini should be resigned as a ransom for their defender. Of this she was informed, and expressed her acquiescence. Having provided wherewithal to secure her from dishonour, she communed with two chiefs of her own kin and clan of Ceylon, her uncle Gora, and his nephew Badal, who devised a scheme for the liberation of their prince without hazarding her life or fame. Intimation was dispatched to Ala that on the day he withdrew from his trenches the fair Padmini would be sent, but in a manner befitting her own and his high station, surrounded by her females and handmaids ; not only those who would accompany her to DeUii, but many others who desired to pay her this last mark of reverence. Strict com mands were to be issued to prevent curiosity from violating the sanctity of female decorum and privacy. No less than seven hundred covered litters proceeded to the royal camp. In each was placed one of the bravest of the defenders of Chitor, borne by six armed soldiers disguised as litter-porters. They reached the camp. The royal tents were enclosed with kanats (walls of cloth) ; the litters were deposited, and half an hour was granted for ji parting interview between the Hindu prince and his bride. They then placed their prince in a litter and returned with him, while the greater number (the supposed damsels) remained to accom pany the fair to Delhi. 1 But Ala had no intention to permit Bhimsi's return, and was becoming jealous of the long interview he enjoyed, when, instead of the prince and Padmini, the devoted band issued from their litters : but Ala was too well guarded. Pursuit was ordered, while these covered the retreat till they perished to a man. A fleet horse was in reserve for [264] Bhimsi, on which he was placed, and in safety ascended the fort, at whose outer gate the host of Ala was encountered. The choicest of the heroes of Chitor met the assault. With Gora and Badal at their head, animated by the noblest sentiments, the deliverance of their chief and the honour of their queen, they devoted them

1 [A folk-tale of the ' Horse of Troy ' type, common in India ; see Rhys Davids, Buddhist India, 4 f. ; Ferishta ii. 115; Grant Duff, Hist. Mahrattas, 64, note ; cf . Herodotus v. 20.] selves to destruction, and few were the survivors of this slaughter of the flower of Mewar. For a tinie Ala was defeated in his object, and the havoc they had made in his ranks, joined to the dread of their determined resistance, obUged him to desist from the enterprise.

Mention has already been made of the adjuration, " by the sin of the sack of Chitor." Of these sacks they enumerate three and a half. This is the ' half ' ; for though the city was not stormed, the best and bravest were cut off (sakha). It is described with great animation in the Khuman Raesa. Badal was but a stripling of twelve, but the Rajput expects wonders from this early age. He escaped, though wounded, and a dialogue ensues between him and his uncle's wife, who desires him to relate how her lord conducted himself ere she joins him. The stripling replies : " He was the reaper of the harvest of battle ; I followed his steps as the humble gleaner of his sword. On the gory bed of honour he spread a carpet of the slain ; a barbarian prince his pillow, he laid him down, and sleeps surrounded by the foe." Again she said : " Tell me, Badal, how did my love (piyar) behave ? " " Oh ! mother, how further describe his deeds when he left no foe to dread or admire him ? " She smiled farewell to the boy, and adding, " My lord will chide my delay," sprung into the flame.

Alau-d-din, having recruited his strength, returned to his object, Chitor. The annals state this to have been in S. 1346 (a.d. 1290), but Ferishta gives a date thirteen years later.1 They had not yet recovered the loss of so many valiant men who had sacrificed themselves for their prince's safety, and Ala carried on his attacks more closely, and at length obtained the hill at the southern point, where he entrenched himself. They still pretend to point out his trenches ; but so many have been formed by subsequent attacks that we cannot credit the assertion. The poet has found in the disastrous issue of this siege admirable materials for his song. He represents the Rana, after an arduous day, stretched on his paUet, and during a night of watchful anxiety, pondering on the means by which he might preserve from the general destruction one at least of his twelve sons ; when a voice [265] broke on his solitude, exclaiming, " Main bhukhi

1 [Chitor was captured in August 1303 (Ferishta i. 353 ; Elliot-Dowson iii. 77).] ho'" ; 1 and raising his eyes, he saw, by the dim glare of the chiragh,2 advancing between the granite columns, the majestic form of the guardian goddess of Chitor. " Not satiated," ex claimed the Rana, " though eight thousand of my kin were late an offering to thee ? " "I must have regal victims ; and if twelve who wear the diadem bleed not for Chitor, the land will pass from the line." This said, she vanished.

On the morn he convened a council of his chiefs, to whom he revealed the vision of the night, which they treated as the dream of a disordered fancy. He commanded their attendance at mid night ; when again the form appeared, and repeated the terms on which alone she would remain amongst them. " Though thousands of barbarians strew the earth, what are they to me ? On each day enthrone a prince. Let the kirania, 2 the chhatra and the chamara, 3 proclaim his sovereignty, and for three days let his decrees be supreme : on the fourth let him meet the foe and his fate. Then only may I remain."

Whether we have merely the fiction of the poet, or whether the scene was got up to animate the spirit of resistance, matters but little, it is consistent with the belief of the tribe ; and that the goddess should openly manifest her wish to retain as her tiara the battlements of Chitor on conditions so congenial to the war like and superstitious Rajput was a gage readily taken up and fully answering the end. A generous contention arose amongst the brave brothers who should be the first victim to avert the denunciation. Arsi urged his priority of birth : he was pro claimed, the umbrella waved over his head, and on the fourth day he surrendered his short-lived honours and his life. Ajaisi, the next in birth, demanded to follow ; but he was the favourite son of his father, and at his request he consented to let his brothers precede him. Eleven had fallen in turn, and but one victim remained to the salvation of the city, when the Rana, calling his chiefs around him, said, " Now I devote myself for Chitor."

The Johar

But another awful sacrifice was to precede this act of self-devotion in that horrible rite, the Johar,4 where the 1 ' I am hungry.' 2 Lamp. 3 These are the insignia of royalty. The kirania is a parasol, from kiran, ' a ray ' : the chhatra is the umbrella, always red ; the chamara, the flowing tail of the wild ox, set in a gold handle, and used to drive away the flies.

4 [Sir G. Grierson informs me that Johar or Jauhar is derived from Jatu females are immolated to preserve theni from pollution or cap tivity. The funeral pyre was lighted within the ' great sub terranean retreat,' in chambers impervious to the light [266] of day, and the defenders of Chitor beheld in procession the queens, their own wives and daughters, to the number of several thou sands. The fair Padmini closed the throng, which was augmented by whatever of female beauty or youth could be tainted by Tatar lust. They were conveyed to the cavern, and the opening closed upon them, leaving them to find security from dishonour in the devouring element.

A contest now arose between the Rana and his surviving son ; but the father prevailed, and Ajaisi, in obedience to his commands, with a small band passed through the enemy's lines, and reached Kelwara in safety. The Rana, satisfied that his line was not extinct, now prepared to follow his brave sons ; and calling around him his devoted clans, for whom life had no longer any charms, they threw open the portals and descended to the plains, and with a reckless despair carried death, or met it, in the crowded ranks of Ala. The Tatar conqueror took possession of an inani mate capital, strewed with brave defenders, the smoke yet issuing from the recesses where lay consumed the once fair object of his desire ; and since this devoted day the cavern has been sacred : no eye has penetrated its gloom, and superstition has placed as its guardian a huge serpent, whose ' venomous breath ' extin guishes the fight which might guide intruders to ' the place of sacrifice.'

The Conquests of Alau-d-dln

Thus fell, in a.d. 1303, this celebrated capital, in the round of conquest of Alau-d-din, one of the most vigorous and warlike sovereigns who have occupied griha, ' a house built of lac or other combustibles,' in allusion to the story in the Mahabliarata (i. chap. 141-151) of the attempted destruction of the Pandavas by setting such a building on fire. For other examples of the rite see Ferishta i. 59 f. ; Elliot-Dowson i. 313, 536 f., iii. 426, 433, iv. 277, 402, V. 101 ; Forbes, Ras Mala, 286 ; Malcolm, Memoir Central India, 2nd ed. 1. 483. For recent cases Irvine, Army of the Indian Moghuls, 242 ; Punjab Notes and Queries, iv. 102 ff.]

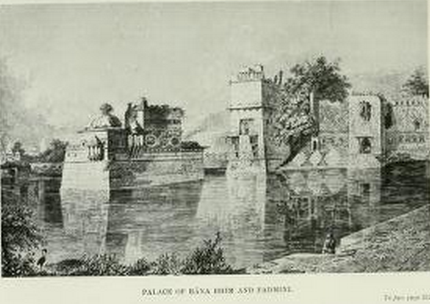

1 The Author has been at the entrance of this retreat, which, according to the Khuman Raesa, conducts to a subterranean palace, but the m.ephitic vapours and venomous reptiles did not invite to adventure, even had official situation permitted such slight to these prejudices. The Author is the only EngUshman admitted to Chitor since the days of Herbert., who appears to have described what he sav.'. the throne of India. In success, and in one of the means of attainment, a bigoted hypocrisy, he bore a striking resemblance to Aurangzeb ; and the title of ' Sikandaru-s-Sani,' or the second Alexander, which he assumed and impressed on his coins, was no idle vaunt. The proud Anhilwara, the ancient Dhar and Avanti, Mandor and Deogir, the seats of the Solankis, the Pramaras, the Pariharas and Taks, the entire Agnikula race, were overturned for ever by Ala. Jaisalmer, Gagraun, Bundi, the abodes of the Bhatti, the Khichi, and the Hara, with many of minor importance, suffered all the horrors of assault from this foe of the race, though destined again to raise their heads. The Rathors of Marwar and the [267] Kachhwahas of Amber were yet in a state of insigni ficance : the former were slowly creeping into notice as the vassals of the Pariharas, while the latter could scarcely withstand the attacks of the original Mina population. Ala remained in Chitor some days, admiring the grandeur of his conquest ; and having committed every act of barbarity and wanton dilapida tion which a bigoted zeal could suggest, overthrowing the temples and other monuments of art, he delivered the city in charge to Maldeo, the chief of Jalor, whom he had conquered and enrolled amongst his vassals. The palace of Bhim and the fair Padmini alone appears to have escaped the wrath of Ala ; it would be pleasing could we suppose any kinder sentiment suggested the exception, which enables the author of these annals to exhibit the abode of the fair of Ceylon.

The Flight of Rana Ajai Singh

The survivor of Chitor, Rana Ajaisi, was now in security at Kelwara, a town situated in the heart of the Aravalli mountains, the western boundary of Mewar, to which its princes had been indebted for twelve centuries of dominion. Kelwara is at the highest part of one of its most ex tensive valleys, termed the Shero Nala, the richest district of this Alpine region. Guarded by faithful adherents, Ajaisi cherished for future occasion the wrecks of Mewar. It was the last behest of his father that when he attained ' one hundred years ' (a figurative expression for dying) the son of Arsi, the elder brother, should succeed him. This injunction, from the deficiency of the qualities requisite at such a juncture in his own sons, met a ready compliance. Hamir was this son, destined to redeem the promise of the genius of Chitor and the lost honours of his race, and whose birth and early history fill many a page of their annals.

His father, Arsi, being out on a hunting excursion in the forest of Ondua, with some young chiefs of the court, in pursuit of the boar entered a field of maize, when a female offered to drive out the game. Pulling one of the stalks of maize, which grows to the height of ten or twelve feet, she pointed it, and mounting the platform made to watch the corn, impaled the hog, dragged him before the hunters, and departed. Though accustomed to feats of strength and heroism from the nervous arms of their country women, the act surprised them. They descended to the stream at hand, and prepared the repast, as is usual, on the spot. The feast was held, and comments were passing on the fair arm which had transfixed the boar, when a baU of clay from a sling fractured a limb of the prince's steed. Looking in the direction whence it [268] came, they observed the same damsel, from her elevated stand,^ preserving her fields from aerial depredators ; but seeing the mischief she had occasioned she descended to express her regret and then returned to her pursuit. As they were pro ceeding homewards after the sports of the day, they again encoun tered the damsel, with a vessel of milk on her head, and leading in either hand a young buffalo. It was proposed, in frolic, to overturn her milk, and one of the companions of the prince dashed rudely by her ; but without being disconcerted, she entangled one of her charges with the horse's limbs and brought the rider to the ground. On inquiry the prince discovered that she was the daughter of a poor Rajput of the Chandano tribe.2 He returned the next day to the same quarter and sent for her father, who came and took his seat with perfect independence close to the prince, to the merriment of his companions, which was checked by Arsi asking his daughter to wife. They were yet more surprised by the demand being refused. The Rajput, on going home, told the more prudent mother, who scolded him heartily, made him recall the refusal, and seek the prince. They were married, and Hamir was the son of the Chandano Rajputni.3

1 A stand is fixed upon four poles in the middle of a field, on which a guard is placed armed with a shng and clay balls, to drive away the ravens, peacocks, and other birds that destroy the corn. 2 One of the branches of the Ghauhan. 3 [The same tale is told of Dhadij, grandson of Prithiraj. the ancestor of the Dahiya Jats (Rose, Glossary, ii. 220 ; Risley, People of India, 2nd ed., 179 f.).] He remained little noticed at the maternal abode till the cata strophe of Chitor. At this period lie was twelve years of age, and had led a rustic Ufe, from which the necessity of the times recalled him.

Mewar occupied by the Musalmans : The Exploit of Hamir

Mewar was now occupied by the garrisons of Delhi, and Ajaisi had besides to contend with the mountain chiefs, amongst whom Munja Balaicha was the most formidable, who had, on a recent occasion, invaded the Shero Nala, and personally encountered the Rana, whom he wounded on the head with a lance. The Rana's sons, Sajansi and Ajamsi, though fourteen and fifteen, an age at which a Rajput ought to indicate his future character, proved of little aid in the emergency. Hamir was summoned, and accepted the feud against Munja, promising to return success ful or not at all. In a few days he was seen entering the pass of Kelwara with Munja's head at his saddle-bow. Modestly placing the trophy at his uncle's feet, he exclaimed : " Recognize the head of your foe ! " Ajaisi ' kissed his beard,' and observing that fate had stamped empire on his forehead, impressed [269] it with a tika of blood from the head of the Balaicha. This decided the fate of the sons of Ajaisi ; one of whom died at Kelwara, and the other, Sajansi, who might have excited a civil war, was sent from the country.'- He departed for the Deccan, where his issue was destined to avenge some of the wrongs the parent country had sustained, and eventually to overturn the monarchy of Hindustan ; for Sajansi was the ancestor of Sivaji, the founder of the Satara throne, whose lineage ' is given in the chronicles of Mewar.

1 This is an idiomatic phrase ; Hamir could have had no beard. 2 Des desa. 3 Ajaisi, Sajansi, DaHpji, Sheoji, Bhoraji, Deoraj, Ugarsen, Mahulji, Kheluji, Jankoji, Satuji, Sambhaji, Sivaji (the founder of the Mahratta nation), Sambhaji, Ramraja, usurpation of the Peshwas. The Satara throne, but for the jealousies of Udaipur, might on the imbecility of Ramraja have been replenished from Mewar. It was offered to Nathji, the grand father of the present chief Sheodan Singh, presumptive heir to Chitor. Two noble hues were reared from princes of Chitor expelled on similar occasions ; those of Sivaji and the Gorkhas of Nepal. [This pedigree is largely the work of the bards. But the Mahrattas, who seem to be chiefly sprung from the Kunbi peasantry, claim Rajput origin, and several of their clans bear Rajput names. It is said that in 1836 the Rana of Mewar was satisfied that the Bhonslas and certain other families had the right to be regarded as Rajputs {Census Report, Bombay, 1901, i. 184 f. ; Russell, Tribes and Castes Central Provinces, iv. 199 fif.).]

Rana Hamir Singh, a.d. 1301-64

Hamir succeeded in S. 1357 (a.d. 1301), and had sixty-four years granted to him to redeem his country from the ruins of the past century, which period had elapsed since India ceased to own the paramount sway of her native princes. The day on which he assumed the ensigns of rule he gave, in the tika daur, an earnest of his future energy, which he signalized by a rapid inroad into the heart of the country of the predatory Balaicha, and captured their stronghold Pusalia. We may here explain the nature of this custom of a barbaric chivalry.

The Inaugural Foray

The tika daur signifies the foray of inauguration, which obtained from time immemorial on such events, and is yet maintained where any semblance of hostility will allow its execution. On the morning of installation, having previously received the tika of sovereignty, the prince at the head of his retainers makes a foray into the territory of any one with whom he may have a feud, or with whom he may be indifferent as to exciting one ; he captures a stronghold or plunders a town, and returns with the trophies. If amity should prevail with all around, which the prince cares not to disturb, they have still a mock representation of the custom. For many reigns after the Jaipur princes united their fortunes to the throne of Delhi their frontier town, Malpura, was the object of the tika daur of the princes of Mewar.

Chitor under a Musahnan Garrison

When Ajmall 1 went another road," as the bard figuratively describes the demise of Rana Ajaisi, " the son of Arsi unsheathed the sword, thence never stranger to his hand." Maldeo remained with the royal garrison at Chitor," but Hamir [270] desolated their plains, and left to his eneinies only the fortified towns which could safely be inhabited. He commanded all who owned his sovereignty either to quit their abodes, and retire with their families to the shelter of the hills on the eastern and western frontiers, or share the fate of the pubhc enemy. The roads were rendered impassable fi'om his parties, who issued from their retreats in the Aravalli, the security 2 This is a poetical version of the name of Ajaisi ; a Uberty frequently taken by the bards for the sake of rhyme. 3 [From an inscription at Chitor it appears that the fort remained in the charge of Muhammadans up to the time of Muhammad Tughlak (1324-51), who appointed Maldeo of Jalor governor (Erskine ii. A. 16). J of which baffled pursuit. This destructive pohcy of laying waste the resources of their own country, and from this asylum attack ing their foes as opportimity offered, has obtained from the time of Mahmud of Ghazni in the tenth, to Muhammad, the last who merited the name of Emperor of Delhi, in the eighteenth century.

Resistance of Hamir Singh

Hamir made Kelwara 1 his resi dence, which soon became the chief retreat of the emigrants from the plams. The situation was admirably chosen, being covered by several ranges, guarded by intricate defiles, and situated at the foot of a pass leading over the mountain into a still more inaccess ible retreat (where Kumbhalmer now stands),2 well watered and wooded, with abundance of pastures and excellent indigenous fruits and roots. This tract, above fifty miles in breadth, is twelve hundred feet above the level of the plains and three thou sand above the sea, with a considerable quantity of arable land, and free communication to obtain supplies by the passes of the western decUvity from Marwar, Gujarat, or the friendly Bhils, of the west, to whom this house owes a large debt of gratitude. On various occasions the communities of Oghna and Panarwa furnished the princes of Mewar with five thousand bowmen, supplied them with provisions, or guarded the safety of their families when they had to oppose the foe in the field. The ele vated plateau of the eastern frontier presented in its forests and deUs many places of security ; but Ala 3 traversed these in person, destroying as he went : neither did they possess the advantages of climate and natural productions arising from the elevation of the other. Such was the state of Mewar : its places of strength occupied by the foe, cultivation and peacefid objects neglected from the persevering hostility of Hamir, when a proposal of marriage came from the Hindu governor of Chitor, wiiich was immediately accepted, contrary to the [271] wishes of the prince's advisers.

The Recovery of Chitor

Whether this was intended as a snare 1 The lake he excavated here, the Hamir-talao, and the temple of the pro tecthig goddess on its bank, still bear witness of his acts while confined to this retreat. 2 See Plate, view of Kumbhalmer. 3 I have an inscription, and in Sanskrit, set up by an apostate chief or bard in his train, which I found in this tract. to entrap him, or merely as an insult, every danger was scouted by Hamir which gave a chance to the recovery of Chitor. He desired that ' the coco-md 1 might he retained, coolly remarking on the dangers pointed out, " My feet shall at least tread in the rocky steps in which my ancestors have moved. A Rajput should always be prepared for reverses ; one day to abandon his abode covered with wounds, and the next to reascend with the maur (crown) on his head." It was stipulated that only five hundred horse should form his suite. As he approached Chitor, the five sons of the Chauhan advanced to meet him, but on the portal of the city no toran,2 or nuptial emblem, was suspended. He, how ever, accepted the unsatisfactory reply to his remark on this indication of treachery, and ascended for the first time the ramp of Chitor. He was received in the ancient halls of his ancestors by Rao Maldeo, his son Banbir, and other chiefs, xvith folded hands. The bride was brought forth, and presented by her father without any of the solemnities practised on such occasions ; ' the knot of their gannents tied and their hands united,' and thus they were left. The family priest recommended jjatience, and Hamir 1 This is the symbol of an offer of marriage. 2 The toran is the symbol of marriage. It consists of three wooden bars, forming an equilateral triangle ; mystic in shape and number, and having the apex crowned with the effigies of a peacock, it is placed over the portal of the bride's abode. At Udaipur, when the princes of Jaisalmer, Bikaner, and Kishangarh sinmltarieously jnarried the two daughters and grand daughter of the Raiia, the torans were suspended from the battlements of the tripolia, or three-arched portal, leading to the palace. The bridegrooni. on horseback, lance in hand, proceeds to break the toran (toran torna), which is defended by the damsels of the bride, who from the parapet assail him with missiles of various kinds, especially with a crimson powder made from the flowers of the palasa, at the same time singing songs fitted to the occa sion, replete with doubie-entendres. At length the toran is broken amidst the shouts of the retainers ; when the fair defenders retire. The simihtude of these ceremonies in the north of Europe and in Asia increases the list of common affinities, and indicates the violence of rude times to obtain the object of affection ; and the lance, with which the Rajput chieftain breaks the toran, has the same emblematic import as the spear, which, at the marri age of the nobles in Sweden, was a necessary implement in the furniture of the marriage chamber (vide Mallett, Northern Antiquities). [The custom perhaps represents a symbol of marriage by capture, but it has also been suggested that it symbolizes the luck of the bride's fam.ily which the bride groom acquires by touching the arch with his sword (see Luard, Ethnographic Survey Central India, 22 ; Enthoven, Folk-lore Notes Gujarat, 69 ; Russell, Tribes and Castes Central Provinces, ii. 410).]

retired with his bride to the apartments allotted for them. Her

kindness and vows of fidelity overcame his sadness upon learning

that he had married a widow. She had been wedded to a chief

of the Bhatti tribe, shortly afterwards slain, and when she was

so young as not to recollect even his appearance. He ceased to

lament the insult when she herself taught him how it might be

avenged, and that it might even lead to the recovery of Chitor.

It is a privilege possessed by the bridegroom to have one specific

favour complied with as a part of the dower (daeja), and Hamir

was instructed by his bride to ask for Jal, one of the civil [272]

officers of Chitor, and of the Mehta tribe. With his wife so ob

tained, and the scribe whose talents remained for trial, he returned

in a fortnight to Kelwara. Khetsi was the fruit of this marriage,

on which occasion Maldeo made over all the hill tracts to Hamir.

Khetsi was a year old when one of the penates (Khetrpal) ^ was

foimd at fault, on which she wrote to her parents to invite her to

Chitor, that the infant might be placed before the shrine of the

deity. Escorted by a party from Chitor, with her child she

entered its walls ; and instructed by the Mehta, she gained over

the troops who were left, for the Rao had gone with his chief

adherents against the Mers of Madri. Hamir was at hand.

Notice that all was ready reached him at Bagor. Still he met

opposition that had nearly, defeated the scheme ; but having

forced admission, his sword overcame every obstacle, and the

oath of allegiance (an) was proclaimed from the palace of his

fathers.

The Sonigira on his return was met with ' a salute of arabas,' 2 and Maldeo himself carried the account of his loss to the Khilji king Mahmud, who had succeeded Ala. The ' standard of the sun ' once more shone refulgent from the walls of Chitor, and was the signal for return to their ancient abodes from their hills and hiding-places to the adherents of Hamir. The valleys of Kum bhalmer and the western highlands poured forth their ' streams of men,' while every chief of true Hindu blood rejoiced at the pros pect of once more throwing off the barbarian yoke. So powerful was this feeling, and with such activity and skill did Hamir follow up this favour of fortune, that he marched to meet Mahmud, 1 [Khetrpal, Kshetrapala, is guardian of the field (Kshetra).] 2 A kind of arquebuss [properly the gun-carriage. Irvine, Army of the Indian Moghuls, 140 ff.] who was advancing to recover his lost possessions. The king unwisely directed his march by the eastern plateau, where numbers were rendered useless by the intricacies of the country. Of the three steppes which mark the physiognomy of this tract, from the first ascent from the plain of Mewar to the descent at Chambal, the king had encamped on the central, at Singoli, where he was attacked, defeated, and made prisoner by Hamir, who slew Hari Singli, brother of Banbir, in single combat. The king suffered a confinement of three months in Chitor, nor was liberated till he had surrendered Ajmer, Ranthambor, Nagor, and Sui Sopur, besides paying fifty lakhs of rupees and one hundred elephants. Hamir would exact no promise of cessation from further in roads, but contented himself with assuring him that from such he sliould be prepared to defend Chitor, not within, but without the walls [273]. 1

Banbir, the son of Maldeo, offered to serve Hamir, who assigned the districts of Nimach, Jiran, Ratanpur, and the Kerar to main tain the family of his wife in becoming dignity ; and as he gave the grant he remarked : " Eat, serve, and be faithful. You were once the servant of a Turk, but now of a Hindu of your own faith ; for I have but taken back my own, the rock moistened by the blood of my ancestors, the gift of the deity I adore, and who will maintain me in it ; nor shall I endanger it by the worship of a fair face, as ditl my predecessor." Banbir shortly after carried Bhainsror by assault, and this ancient possession guarding the Chambal was again added to Mewar.. The chieftains of Rajasthan rejoiced once more to see a Hindu take the lead, paid willing homage, and aided him with service when required.

The Power of Rana Hamir Singh

Hamir was the sole Hindu prince of power now left in India : all the ancient dynasties were 1 Ferishta does not mention this conquest over the Khilji emperor ; but as Mewar recovered her wonted splendour in this reign, we cannot doubt the truth of the native annals. [There is a mistake here. The successor of Alau-d-dln was Kutbu-d-din Mubarak, who came to the throne in 1316. Ferishta says that Rai Ratan Singh of Chitor, who had been taken prisoner in the siege, was released by the cleverness of his daughter, and that Alau d-din ordered his son, Khizr Khan, tO evacuate the place, on which the Rai became tributary to Alau-d-dln. Also in 1312 the Rajputs threw the Muhammadan officers over the ramparts and asserted their independence (Ferishta, trans. Briggs, i. 363, 381). Erskine says that the attack was made by Muhammad Tughlak (1324-51).] crushed, and the ancestors of the present princes of Marwar and Jaipur brought their levies, paid homage, and obeyed the summons of the prince of Chitor, as did the chiefs of Bundi, Gwalior, Chan deri, Raesin, Sikri, Kalpi, Abu, etc.

Extensive as was the power of Mewar before the Tatar occu pation of India, it could scarcely have surpassed the solidity of sway which she enjoyed during the two centuries following Hamir's recovery of the capital. From this event to the next invasion from the same Cimmerian abode, led by Babur, we have a succession of splendid names recorded in her annals, and though destined soon to be surrounded by new Muhammadan dynasties, in Malwa and Gujarat as well as Delhi, yet successfully opposing them all. The distracted state of affairs when the races of Khilji, Lodi, and Sur alternately struggled for and obtained the seat of dominion, Delhi, was favourable to Mewar, whose power was now so consolidated that she not only repelled armies from her territory, but carried war abroad, leaving tokens of victory at Nagor, in Saurashtra, and to the walls of Delhi.

Public Works

The subjects of Mewar must have enjoyed not only a long repose, but high prosperity during this period, judging from their magnificent public works, when a triumphal [274] column must have cost the income of a kingdom to erect, and which ten years' produce of the crown-lands of Mewar could not at this time defray. Only one of the structures prior to the sack of Chitor was left entire by Ala, and is yet existing, and this was raised by private and sectarian hands. It would be curious if the unitarian profession of the Jain creed was the means of preserving this ancient relic from Ala's wrath.1 The princes of this house were great patrons of the arts, and especially of architecture ; and it is a matter of surprise how their revenues, derived chiefly from the soil, could have enabled them to expend so much on these objects and at the same time maintain such armies as are enumerated. Such could be effected only by long prosperity and a mild, paternal system of government ; for the subject had his monuments as well as the prince, the ruins of which may yet be discovered in the more inaccessible or deserted portions of Rajasthan. Hamir died fuU of years, leaving a name still

1 [The Jain tower, kaowu as Kirtti Stamb, ' pillar of fame,' erected in the twelfth or thirteenth century by Jija, a Bagherwal Mahajan, and dedicated to Adinath, the first Jain TIrthankara or saint.] honoured in Mewar, as one of the wisest and most gallant of her princes, and bequeathing a well-established and extensive power to his son.

Kshetra or Khet Singh, a.d. 1364-82

Khetsi succeeded in S. 1421 (a.d. 1365) to the power and to the character of his father. He captured Ajnier and Jahazpur from Lila Pathan, and rean nexed Mandalgarh, Dasor, and the whole of Chappan (for the first time) to Mewar. He obtained a victory over the Delhi monarch Humayun 1 at Bakrol ; but unhappily his life terminated in a. family broil with his vassal, the Hara chief of Bumbaoda, whose daughter he was about to espouse.

Laksh Singh, a.d. 1382-97

LakhaRana, by this assassination, mounted the throne in Chitor in S. 1439 (a.d. 1373). His first act was the entire subjugation of the mountainous region of Merwara, and the destruction of its chief stronghold, Bairatgarh, where he erected Badnor. But an event of much greater importance than settling his frontier, and which most powerfully tended to the prosperity of the country, was the discovery of the tin and silver mines of Jawara, in the tract wrested by Khetsi from the Bhils of Chappan. 2 Lakha Rana has the merit of having first worked them, though their existence is superstitiously alluded to so early as the period of the founder. It is said the ' seven metals ' {haft dhat) 3 were formerly [275] abundant ; but this appears figura tive. We have no evidence for the gold, though silver, tin, copper, lead, and antimony were yielded in abundance (the first two from the same matrix), but the tin that has been extracted for many years past yields but a small portion of silver.4 Lakha Rana defeated the Sankhla Rajputs of Nagarchal,5 at Amber. He encountered the emperor Muhammad Shah Lodi, and on one

1 [The contemporary of Khet Singh at Delhi was Firoz Shah Tughlak.] 2 [The mines at Jawar, sixteen miles south of Udaipur city, produce lead, zinc, and some silver. The mention of tin in the text seems wrong (Watt, Diet. Econ. Prod. vi. Part iv. 356 ; Gomm. Prod. 1077).] 3 Haft-dhat, corresponding to the planets, each of which ruled a metal : hence Mihr, ' the sun,' for gold ; Chandra, ' the moon,' for silver. 4 They have long been abandoned, the miners are extinct, and the pro tecting deities of mines are unable to get even a flower placed on their shrines, though some have been reconsecrated by the Bhils, who have con verted Lakshun into Sitalamata (Juno Lucina), whom the Bhil females invoke to pass them through danger.

4 Jhunjhunu, Singhana, and Narbana formed the ancient Nagarchal territory. . VOL. I • Y occasion defeated a royal army at Badnor ; but he carried the war to Gaya, and in driving the barbarian from this sacred place was slain.1 Lakha is a name of celebrity, as a patron of the arts and benefactor of his country. He excavated many reservoirs and lakes, raised immense ramparts to dam their waters, besides erecting strongholds. The riches of the mines of Jawara were expended to rebuild the temples and palaces levelled by Ala. A portion of his own palace yet exists, in the same style of archi tecture as that, more ancient, of Ratna and the fair Padmini ; and a minster (mandir) dedicated to the creator (Brahma), an enormous and costly fabric, is yet entire. Being to ' the One,' and consequently containing no idol, it may thus have escaped the ruthless fury of the invaders. Lakha is a name of celebrity, as a patron of the arts and benefactor of his country. He excavated many reservoirs and lakes, raised immense ramparts to dam their waters, besides erecting strongholds. The riches of the mines of Jawara were expended to rebuild the temples and palaces levelled by Ala. A portion of his own palace yet exists, in the same style of archi tecture as that, more ancient, of Ratna and the fair Padmini ; and a minster (mandir) dedicated to the creator (Brahma), an enormous and costly fabric, is yet entire. Being to ' the One,' and consequently containing no idol, it may thus have escaped the ruthless fury of the invaders. Lakha had a numerous progeny, who have left their clans called after them, as the Lunawats and Dulawats, now the sturdy allodial proprietors of the Alpine regions bordering on Oghna, Panarwa, and other tracts in the Aravalli. 2

But a circumstance which set aside the rights of primogeniture, and transferred the crown of Chitor from his eldest son, Chonda, to the younger, Mokal, had nearly carried it to another line. The consequences of making the elder branch a powerful vassal clan with claims to the throne, and which have been the chief cause of its subsequent prostration, we will reserve for another chapter [276].