Mewar 30: Reform of the Nobility

This page is an extract from OR THE CENTRAL AND WESTERN By Edited with an Introduction and Notes by In Three Volumes HUMPHREY MILFORD |

Note: This article is likely to contain several spelling mistakes that occurred during scanning. If these errors are reported as messages to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com your help will be gratefully acknowledged.

Mewar 30: Reform of the Nobility

Reform of the Nobility

Of the three measures simultaneously projected and pursued for the restoration of prosperity, the industrious portion has been described. The feudal interest remains, which was found the most difficult to arrange. The agricultural and commercial classes required only protection and stimulus, and we could repay the benefits their industry conferred by the lowest scale of taxation, which, though in fact equally beneficial to the government, was constructed as a boon. But with the feudal lords there was no such equivalent to offer in return for the sacrifices many had to make for the re-establishment of society. Those who were well inclined, like Kotharia, had everything to gain, and nothing left to surrender ; while those who, like Deogarh, Salumbar, or Badnor, had preserved their power by foreign aid, intrigue, or prowess, dreaded the high price they might be called upon to pay [486] for the benefit of security which the new alliance conferred. All dreaded the word ' restitu tion,' and the audit of half a century's political accounts ; yet the adjustment of these was the corner-stone of the edifice, which anarchy and oppression had dismantled. Feuds were to be appeased, a difficult and hazardous task ; and usurpations, both on the crown and each other, to be redeemed. ' To bring the wolf and the goat to drink from the same vessel,' was a task of less difficulty than to make the Chondawat and Saktawat labour in concert for the welfare of the prince and the country. In fine, a better idea cannot be afforded of what was deemed the hopeless

1 Although Bhilwara has not attained that high prosperity my enthusiasm anticipated, yet the philanthropic Heber records that in 1825 (three years after I had left the country) it exhibited " a greater appearance of trade, industry, and moderate but widely diffused wealth and comfort, than he had witnessed since he left DehU" [Diary, ed. 1861, ii. 56 f.]. The record of the sentiments of the inhabitants towards me, as conveyed by the bishop, was gratifying, though their expression could excite no surprise in any one acquainted with the characters and sensibilities of these people. [The author's anticipation of the prosperity of this town have not been com pletely realized ; but it is still an important centre of trade, noted for the manufacture of cooking utensils, and possessing a ginning factory and a cotton-press (Erskine ii. A. 97 f.)-l ness of success than the opinion of Zorawar Singh, the chief of the latter clan, who had much to relinquish : " Were Parameswara (the Almighty) to descend, he could not reform Mewar." We judged better of them than they did of each other.

Negotiations with the Chiefs

It were superfluous to detail all the preparatory measures for the accomplishment of this grand object ; the meetings and adjournments, which only served to keep alive discontent. On the 27th of April, the treaty with the British Government was read, and the consequent change in their relations explained. Meanwhile; a charter, defining the respective rights of the crown and of the chiefs, with their duties to the community, was prepared, and a day named for a general assembly of the chieftains to sanction and ratify this engagement. The 1st of May was fixed : the chiefs assembled ; the articles, ten in number, were read and warmly discussed ; when with unmeaning expressions of duty, and objections to the least prominent, they obtained through their speaker, Gokuldas of Deogarh, permission to reassemble at his house to consider them, and broke up with the promise to attend next day. The delay, as apprehended, only generated opposition, and the 2nd and 3rd passed in inter-com munications of individual hope and fear. It was important to put an end to speculation. At noon, on the 4th of May, the grand hall was again filled, when the Rana, with his sons and ministers, took their seats. Once more the articles were read, objections raised and combated, and midnight had arrived without the object of the meeting being advanced, when an adjournment, proposed by Gokuldas, till the arrival of the Rana's plenipotentiary from Delhi, met with a firm denial ; and the Rana gave him liberty to retire, if he refused his testimony of loyalty. The Begun chief, who had much to gain, at length set the example, followed by the chiefs of Amet and Deogarh, and in succession by all the sixteen nobles, who also signed as the proxies of their [487] relatives, unable from sickness to attend. The most powerful of the second grade also signed for themselves and the absent of their clans, each, as he gave in his adhesion, retiring ; and it was three in the morning of the 5th of May ere the ceremony was over. The chief of the Saktawats, determined to be conspicuous, was the last of his own class to sign. During this lengthened and painful discussion of fifteen hours' continuance, the Rana con ducted himself with such judgment and firmness, as to give sanguine hopes of his taking the lead in the settlement of his affairs.

Enforcement of the Treaty

This prehunnary adjusted, it was important that the stipulations of the treaty 1 should be rigidly if not rapidly effected. It will not be a matter of surprise, that some months passed away before the complicated arrangements arising out of this settlement were completed ; but it may afford just grounds for gratulation, that they were finally accomplished without a shot being fired, or the exhibition of a single British soldier in the country, nor, indeed, within one hundred miles of Udaipur. ' Opinion ' was the sole and all-sufficient ally effecting this political reform. The Rajputs, in fact, did not require the demonstration of our physical strength ; its influence had reached far beyond Mewar. When the few firelocks defeated hundreds of the foes of public tranquillity, they attributed it to ' the strength of the Company's salt,' 2 the inoral agency of which was pro claimed the true basis of our power. ' Sachha Raj ' was the proud epithet applied by our new allies to the British Government in the East ; a title which distinguished the immortal Alfred, ' the upright.' It will readily be imagined that a reform, which went to touch

1 A literal translation of this curious piece of Hindu legislation will be found at the end of the Appendix. If not drawn up with all the dignity of the legal enactments of the great governments of the West, it has an important advantage in conciseness ; the articles cannot be mismterpreted, and require no lawyer to expound them. 2 " Kampani Sahib ke namak ke zor se " is a common phrase of our native soldiery ; and " Dohai ! Kampani ki ! " is an invocation or appeal against injustice ; but I never heard this watchword so powerfully apphed as when a Sub. with the Resident's escort in 1812. One of our men, a noble young Rajput about nineteen years of age, and six feet high, had been sent with an elephant to forage in the wilds of Narwar. A band of at least fifty predatory horsemen assailed him, and demanded the surrender of the elephant, which he met by pointing his musket and givuig them defiance. Beset on all sides, he fired, was cut down, and left for dead, in which state he was found, and brought to camp upon a litter. One sabre-cut had opened the back entirely across, exposing the action of the viscera, and his arms and wrists were barbarously hacked : yet he was firm; collected, and even cheer ful ; and to a kmd reproach for his rashness, ho said, " What would you have said, Captam Sahib, had I surrendered the Company's musket {Kam pani ki banduq) without fightmg ? " From their temperate habits, the wound in the back did well ; but the severed nerves of the wrists brought on a lockjaw of which he died. The Company have thousands who would alike die for their banduq. It were wise to cherish such feelings. the entire feudal association, could not be accomplished without harassing and painful discussions [488], when the object was the renunciation of lands, to which in some cases the right of inherit ance could be pleaded, in others, the cognisance of successful revenge, while to many prescriptive possession could be asserted. It was the more painful, because although the shades which marked the acquisition of such lands were varied, no distinction could be made in the mode of settlement, namely, unconditional surrender. In some cases, the Rana had to revoke his own grants, wrung either from his necessities or his weakness ; but in neither predicament could arguments be adduced to soften renunciation, or to meet the powerful and pathetic and often angry appeals to justice or to prejudice. Counter-appeals to their loyalty, and the necessity for the re-establishment of their sovereign's just weight and influence in the social body, without which their own welfare could not be secured, were adduced ; but individual views and passions were too absorbing to bend to the general interest. Weeks thus passed in interchange of visits, in soothing pride, and in flattering vanity by the revival of past recollections, which gradually familiarized the subject to the mind of the chiefs, and brought them to compliance. Time, conciliation, and impartial justice, confirmed the victory thus obtained ; and when they were made to see that no interest was overlooked, that party views were miknown, and that the system included every class of society in its beneficial operation, cordiality followed concession. Some of these cessions were alienations from the crown of half a century's duration.

Individual cases of hardship were unavoidable without incurring the imputation of favouritism, and the dreaded revival of ancient feuds, to abolish which was indispensable, but required much circiunspection. Castles and lands in this predicament could therefore neither be retained by the possessor nor returned to the ancient proprietor without rekindling the torch of cival war. The sole alternative was for the crown to take the object of con tention, and make compensation from its own domain. It would be alike tedious and tminteresting to enter into the details of these arrangements, where one chief had to relinquish the levy of transit duties in the most important outlet of the country, asserted to have been held during seven generations, as in the case of the chief of Deogarh. Of another (the Bhindar chief) who held forty three towns and villages, in addition to his grant ; of Amet, of Badesar, of Dabla, of Lawa, and many others who held important fortresses of the crown independent of its will ; and other claims, embracing every right [489] and privilege appertaining to feudal society ; suffice it, that in six months the whole arrangements were effected.

The Case of Arja

In the painful and protracted discussions attendant on these arrangements, powerful traits of national character were developed. The castle and domain of Arja half a century agd belonged to the crown, but had been usurped by the Purawats, from whom it was wrested by storm about fifteen years back by the Saktawats, and a patent sanctioning possession was obtained, on the payment of a fine of £1000 to the Rana. Its surrender was now required from Fateh Singh, the second brother of Bhindar, the head of this clan ; but being regarded as the victorious completion of a feud, it was not easy to silence their prejudices and objections. The renunciation of the forty-three towns and villages by the chief of the clan caused not half the excitation, and every Saktawat seemed to forgo his individual losses in the common sentiment expressed by their head : " Arja is the price of blood, and with its cession our honour is surrendered." To preserve the point of honour, it was stipulated that it should not revert to the Purawats, but be incorporated with the fisc, which granted an equivalent ; when letters of surrender were signed by both brothers, whose conduct throughout was manly and confiding.

Badnor and Amet

The Badnor and Amet chiefs, both of the superior grade of nobles, were the most formidable obstacles to the operation of the treaty of the 4th of May. The first of these, by name Jeth Singh {the victoriowi [chief] lion), was of the Mertia clan, the bravest of the brave race of Rathor, whose ancestors had left their native abodes on the plains of Marwar, and accom panied the celebrated Mira Bai on her marriage with Rana Kmnbha. His descendants, amongst whom was Jaimall, of immortal memory, enjoyed honour in Mewar equal to their birth and high deserts. It was the more difficult to treat with men like these, whose conduct had been a contrast to the general license of the times, and who had reason to feel offended, when no distinction was observed between them and those who had disgraced the name of Rajput. Instead of the submission ex pected from the Rathor, so overwhelmed was he from the magni tude of the claims, which amounted to a virtual extinction of his power, that he begged leave to resign his estates and quit the country. In prosecution of this design, he took post in the chief hall of the palace, from which no entreaties could make him move ; 1 until the Rana, to [490] escape his importimities, and even restraint, obtained his promise to abide by the decision of the Agent. The forms of the Rana's court, from time immemorial, prohibit all personal communication between the sovereign and his chiefs in matters of individual interest, by which indecorous altercation is avoided. But the ministers, whose office it was to obtain every information, did not make a rigid scrutiny into the title-deeds of the various estates previous to advancing the claims of the crown. This brave man had enemies, and he was too proud to have recourse to the common arts either of adulation or bribery to aid his cause. It was a satisfaction to find that the two principal towns demanded of him were embodied in a grant of Sangram Singh's reign ; and the absolute rights of the fisc, of which he had become possessed, were cut down to about fifteen thousand rupees of annual revenue. But there were other points on which he was even more tenacious than the sm-render of these. Being the chief noble of the fine district of Badnor, which consisted of three hundred and sixty towns and villages, chiefly of feudal allotments (many of them of his own clan), he had taken advantage of the times to establish his influence over them, to assume the right of wardship of minors, and secure those services which were due to the prince, but which he wanted the power to enforce. The holders of these estates were of the third class of vassals or gol (the mass), whose services it was important to reclaim, and who constituted in past times the most efficient force of the Ranas, and were the preponderating balance of their authority when mercenaries were unknown in these patriarchal states. Abundant means towards a just investigation had been previously prociu'ed ; and after some discussion, in which all admissible claims were recognized, and argument was silenced by incontrovertible facts, this chieftain relinquished all that was demanded, and sent in, as from himself, his written renunciation to his sovereign. However convincing the data by which his proper rights and those of his prince were defined; it was to feeling

1 [An instance of the practice of ' sitting dharna ' to enforce a claim (Yule-Bumell, Hobaon-Jobson, 2nd ed. 315 f.).] and prejudice that we were mainly indebted for so satisfactory an adjustment. An appeal to the nam,e 1 and the contrast of his ancestor's loyalty and devotion with his own contumacy, acted as a talisman, and wrung tears from his eyes and the deed from his hand. It will afford some idea of the difficulties encountered, as well as the invidiousness of the task of arbitrating such matters, to give his own comment verbatim : "I remained faithful when his own kin deserted him, and was [491] one of four chiefs who alone of all Mewar fought for him in the rebellion ; but the son of Jaimall is forgotten, while the ' plunderer ' is his boon companion, and though of inferior rank, receives an estate which elevates him above me " ; alluding to the chief of Badesar, who plundered the queen's dower. But while the brave descendant of Jaimall returned to Badnor with the marks of his sovereign's favour, and the applause of those he esteemed, the ' runner ' went back to Badesar in disgrace, to which his prince's injudicious favour further contributed.

Hamira of Badesar

Hamira of Badesar was of the second class of nobles, a Chondawat by birth. He succeeded to his father Sardar Singh, the assassin of the prime minister even in the palace of his sovereign ; 2 into whose presence he had the audacity to pursue the surviving brother, destined to avenge him.' Hamira inherited all the turbulence and disaffection, with the estates, of his father ; and this most conspicuous of the many lawless chieftains of the times was known throughout Rajasthan as Hamira ' the runner ' (daurayat). Though not entitled to hold 1 See p. 380. 2 See p. 514 and note. 3 It win fill up the picture of the times to relate the revenge. When Jauishid, the infamous lieutenant of the infamous Amir Khan, established ' his headquarters at Udaipur, which he daily devastated, Sardar Singh, then in power, was seized and confined as a hostage for the payment of thirty thousand rupees demanded of the Rana. The surviving brothers of the murdered minister Somji ' purchased their foe ' with the sum demanded, and anticipated his clansmen, who were on the point of effecting his liberation. The same sun shone on the head of Sardar, which was placed as a signal of revenge over the gateway of Ranipiyari's palace. I had the anecdotes from the minister Siyahal, one of the actors in these tragedies, and a relative of the brothers, who were all swept away by the dagger. A similar fate often seemed to him, though a brave man, inevitable during these resumptions ; which impression, added to the Rana's known inconstancy of favour, robbed him of half his energies. lands beyond thirty thousand annually, he had become possessed to the amount of eighty thousand, chiefly of the fisc or khalisa, and nearly all obtained by violence, though since confirmed by the prince's patent. With the chieftain of Lawa (precisely in the same predicament), who held the fortress of Kheroda and other valuable lands, Hamira resided entirely at the palace, and obtain ing the Rana's ear by professions of obedience, kept possession, while chiefs in eveiy respect his superiors had been compelled to surrender ; and when at length the Saktawat of Lawa was forbid the court until Kheroda and all his usurpations were yielded up, the son of Sardar displayed his usual turbulence, ' curled his moustache ' at the minister, and hinted at the fate of his pre decessor.

Although none dared to imitate him, his stubbornness was not without admirers, especially among his own clan ; and as it was too evident that fear or favour swayed the Rana, it was a case for the Agent's interference, the opportunity for which was soon afforded. When [492] forced to give letters of surrender, the Rana's functionaries, who went to take possession, were insulted, refused admittance, and compelled to return. Not a moment could be lost in punishing this contempt of authority ; and as the Rana was holding a court when the report arrived, the Agent requested an audience. He found the Rana and his chiefs assembled in ' the balcony of the sun,' and amongst them the notorious Hamira. After the usual compliments, the Agent asked the minister if his master had been put in possession of Syana. It was evident from the general constraint, that all were acquainted with the result of the deputation ; but to remove responsibility from the minister, the Agent, addressing the Rana as if he were in ignorance of the insult, related the transaction, and observed that his government would hold him culpable if he remained at Udaipur while his highness's commands were disregarded. Thus supported, the Rana resumed his dignity, and in forcible language signified to all present his anxious desire to do nothing which was harsh or ungracious ; but that, thus compelled, he would not recede from what became him as their sovereign. Calling for a bira, he looked sternly at Hamira, and commanded him to quit his presence instantly, and the capital in an hour ; and, but for the Agent's interposition, he would have been banished the country. Confiscation of his whole estate was commanded, until renunciation was completed. He departed that night ; and, contrary to expectation, not only were all the usurpations sur rendered, but, what was scarcely contemplated by the Agent, the Rana's flag of sequestration was quietly admitted into the fortress of Badesar.1

The Case of Amli

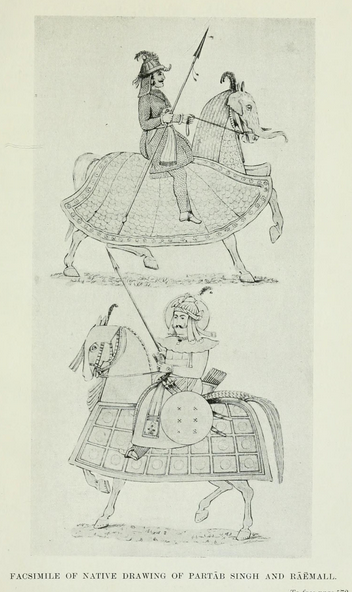

One more anecdote may suffice. The lands and fortress of Amli had been in the family of Amet since the year 27, only five years posterior to the date to which these arrangements extended ; their possession verged on half a century. The lords of Amet were of the Sixteen, and were chiefs of the clan Jagawat. The present representative enjoyed a fair character : he could, with the chief of Radnor, claim the succession of the loyal ; for Partap and Jaimall, their respective ancestors, were rivals and martyrs on that memorable day when the genius of Chitor abandoned the Sesodias. But the heir of Amet had not this alone [493] to support his claims ; for his predecessor Partap had lost his life in defending his country against the Mahrattas, and Amli had been his acquisition. Fateh Singh (such was his name) was put forward by the more artful of his immediate kin, the Chondawat interest ; but his disposition, blunt and impetuous, was Uttle calculated to promote their views : he was an honest Rajput, who neither could nor cared to conceal his anger, and at a ceremonious visit paid him by the Agent, he had hardly sufficient control over himself to be courteous, and though he said nothing, his eyes, inflamed with opium and disdain, spoke his feelings. He maintained a dogged indifference, and was inaccessible to argument, till at length, following the example of Badnor, he was induced to abide by the Agent's mediation. He came attended by his vassals, who anxiously awaited the result, which an un premeditated incident facilitated. After a long and fruitless expostulation, he had taken refuge in an obstinate silence ; and seated in a chair opposUe to the envoy, with his shield in front, placed perpendicularly on his knees, and his arms and head

1 Nearly twelve months after this, my pubhc duty called me to Nimbahera en route to Kotah. The castle of Haraira was within an hour's ride, and at night he was reported as having arrived to visit me, when I appointed the next day to receive him. Early next morning, according to custom, I took my ride, with four of Skinner's Horse, and galloped past him, stretched with his followers on the ground not far from my camp, towards his fort. He came to me after breakfast, called me his greatest friend, " swore by his dagger he was my Rajput," and that he would be in future obedient and loyal ; but this, I fear, can never be. reclined thereon, he continued vacantly looking on the ground. To interrupt this uncourteous silence in his own house, the envoy took a picture, which with several others was at hand, and placing it before him, remarked, " That chief did not gain his reputation for swamidharma 1 (loyalty) by conduct such as yours." His eyes suddenly recovered their animation and his countenance was lighted with a smile, as he rapidly uttered, " How did you why does this interest you ? " A tear started in " Yes," said the Agent, " it is the loyal Partap on the day he went forth to meet his death ; but his name yet lives, and a stranger does homage to " Take Amli, take Amli," he hurriedly repeated, with a suppressed tone of exultation and sorrow, " but forget not the extent of the sacrifice." To prolong the visit would have been painful to both, but as it might have been trusting too much to humanity to delay the resumption, the Agent availed himself of the moment to indite the chhorchitthi 2 of surrender for the lands.

With these instances, characteristic of individuals and the times, this sketch of the introductory measures for improving the condition of Mewar may be closed. To enter more largely in detail is foreign to the purpose of the work ; nor is it requisite for the comprehension of the unity of the object, that a more minute dissection of the parts should be afforded. Before, how ever, we exhibit the [494] general results of these arrangements, we shall revert to the condition of the more humble, but a most important part of the community, the peasantry of Mewar ; and embody, in a few remarks, the fruits of observation or inquiry, as to their past and present state, their rights, the establishment of them, their infringement, and restitution. On this subject much has been necessarily introduced in the sketch of the feudal system, where landed tenures were discussed ; but it is one on which such a contrariety of opinion exists, that it may be desirable to show the exact state of landed tenures in a country, where Hindu manners should exist in greater purity than in any other jjart of the vast continent of India.

The Landed System

The ryot (cultivator) is the proprietor of the soil in Mewar. He compares his right therein to the akshay 1 Literally faith (dharma) to his lord {swami). 2 Paper of relinquishment.

duha,1 which no vicissitudes can destroy. IJe calls the land his bapota, the most emphatic, the most ancient, the most cherished, and the most significant phrase his language commands for patrimonial 2 inheritance. He has nature and Manu in support of his claim, and can quote the text, alike compulsory on prince and peasant, " cultivated land is the property of him who cut away the wood, or who cleared and tilled it," 3 an ordinance binding on the whole Hindu race, and which no international wars, or conquest, could overturn. In accordance with this principle is the ancient adage, not of Mewar only but all Rajpu tana, Bhog ra dhanni Raj ho : bhum ra dhanni ma cho : ' the government is owner of the rent, but I am the master of the land.' With the toleration and benevolence of the race the conqueror is conunanded " to respect the deities adored by the conquered, also their virtuous priests, and to establish the laws of the conquered nation as declared in their books." 4 If it were deemed desirable to recede to the system of pure Hindu agrarian law, there is no deficiency of materials. The customary laws contained in the various reports of able men, superadded to the general ordinances of Manu, would form a code at once simple and efficient : for though innovation from foreign conquest has placed niany principles in abeyance, and modified others, yet he has observed to little purpose [495] who does not trace a uni formity of design, which at one time had ramified wherever the 1 The dub grass Cynodon dactylon] flourishes in all seasons, and most in the intense heats ; it is not only amara or ' immortal,' but akshay, ' not to be eradicated ' ; and its tenacity to the soil deserves the distinction. 2 From bap, ' father,' and the termination of, or belonging to, and by which clans are distinguished ; as Karansot, ' descended of Karan ' ; Mansinghgot, ' descended of Mansingh.' It is curious enough that the mountain clans of Albania, and other Greeks, have the same distinguishing termination, and the Mainote of Greece and the Mairot of Rajputana aUke signify mountaineer, or ' of the mountain,' maina in Albanian ; mairu or meru in Sanskrit. [The words have no connexion.] 3 Laws, ix. 44. 4 [" When he [the king] has gained victory, let him duly worship the gods and honour righteous Brahmanas, let him grant exemptions, and let him cause promises of safety to be proclaimed. But having fully ascer tained the wishes of all the (conquered), let him place then a relation of (the vanquished ruler on the throne), and let him impose his conditions. Let him make authoritative the lawful customs of the inhabitants, just as they are stated to be " (Manu, Laws, vii. 201 f., trans. Buhler, Sacred Books of the East, xxv. 248 f.).] name of Hindu prevailed : language has been modified, and terms have been corrupted or changed, but the primary pervading principle is yet perceptible ; and whether we examine the systems of Khandesh, the Carnatic, or Rajasthan, we shall discover the elements to be the same.

If we consider the system from the period described by Arrian, Curtius, and Diodorus, we shall see in the government of town ships each commune an ' imperium in imperio ' ; a little republic, maintaining its municipal legislation independent of the monarchy, on which it relies for general support, and to which it pays the bhog, or tax in kind, as the price of this protection ; for though the prescribed duties of kings are as well defined by Manu 1 as by any jurisconsult in Europe, nothing can be more lax than the mutual relations of the governed and governing in Hindu mon archies, which are resolved into unbounded liberty of action. To the artificial regulation of society, which leaves all who depend on manual exertion to an immutable degradation, must be ascribed these multitudinous governments, unknown to the rest of mankind, which, in spite of such dislocation, maintain the bonds of mutual sympathies. Strictly speaking, every State presents the picture of so many hundred or thousand minute republics, without any connexion with each other, giving allegi ance {an) and rent (bhog) to a prince, who neither legislates for them, nor even forms a police for their internal protection. It is consequent on this want of paramount interference that, in matters of police, of justice, and of law, the communes act for themselves ; and from this want of paternal interference only have arisen those courts of equity, or arbitration, the panchayats. But to return to the freehold ryot of Mewar, whose hapota is words of foreign growth, introduced by the Muhammadan conquerors ; the first (Persian) is of more general use in Khandesh ; the other (Arabic)

1 [" Let him [the king] cause his annual revenue in his kingdom to be collected by trusty (officials), let him obey the sacred law (in his trans actions with) the people, and behave as a father to all men " (Manu, Laws, vii. 80). " Not to turn back in battle, to protect the people, to honour the Brahmanas, is the best means for a king to secure happmess " {ib. vii. 88). " From the people let him (the king) learn (the theory) of the (various) trades and professions " {ib. vii. 43). " But (he who is given) to these vices (loses) even his life " {ib. vii. 46), trans. Buhler, Sacred Books of the East, xxv.] in the Carnatic. Thus the great Persian moralist Saadi exempli fies its application : " If you desire to succeed to your father's inheritance (miras), first obtain his wisdom " [496]. While the term bapota thus implies the inheritance or patri mony, its holder, if a military vassal, is called Bhumia, a term equally powerful, meaning one actually identified with the soil (bhum), and for which the Muhammad an has no equivalent but in the possessive compound watandar, or mirasdar. The Cani atchi ^ of Malabar is the Bhumia of Rajasthan.

The emperors of Delhi, in the zenith of their power, bestowed the epithet zamindar upon the Hindu tributary sovereigns : not out of disrespect, but in the true application of their own term Bhumia Raj, expressive of their tenacity to the soil ; and this fact affords additional evidence of the proprietary right being in the cultivator {ri/ot), namely, that he alone can confer the freehold land, which gives the title of Bhumia, and of which both past history and present usage will furnish us with examples. When the tenure of land obtained from the cultivator is held more valid than the grant of the sovereign, it will be deemed a conclusive argument of the proprietary right being vested in the ryot. What should induce a chieftain, when inducted into a perpetual fief, to establish through the ryot a right to a few acres in bhum, but the knowledge that although the vicissitudes of fortune or of favour may deprive him of his aggregate signiorial rights, his claims, derived from the spontaneous favour of the commime, can never be set aside ; and when he ceases to be the lord, he becomes a member of the commonwealth, merging his title of Thakur, or Signior, into the more humble one of Bhumia, the allodial tenant of the Rajput feudal system, elsewhere discussed.2 Thus we have touched on the method by which he acquires this distinction, for protecting the conmiunity from violence ; and if left destitute by the negligence or inability of the government, he is vested with the rights of the crown, in its share of the bhog or rent. But when their own land is in the predicament caUed galita, or reversions from lapses to the commune, he is ' seised ' in

1 Cani, ‘land’ and atchi’ heritage’: Report, P. 280._I should be in clined to

imagine the atchi, Uke the ot and awat, Rajput terminations,

implymg clanship. [Tamil kdniydtchi, ' that which is held in free and

hereditary property ' ; kdni, ' land,' atchi, ' inheritance ' (Wilson, Glossary,

s.v. ; Madras Manual of Administration, iii. 58).]

2 See p. 195.

all the rights of the former proprietor ; or, by internal arrange

ments, they can convey such right by cession of the commune.

The Bhumia

The privilege attached to the bhum,1 and acquired from the community by the protection afforded to it, is the most powerful argument for the recognition of its original rights. The Bhumia, thus vested, may at pleasure drive his own plough [497], the right to the soil. His hhum is exempt from the jarib (measuring rod) ; it is never assessed, and his only sign of allegiance is a quit-rent, in most cases triennial, and the tax of kharlakar,2 a war imposition, now commuted for money. The State, however, indirectly receives the services of these allodial tenants, the yeomen of Rajasthan, who constitute, as in the districts of Kumbhalmer and Mandalgarh, the landwehr, or local militia. In fact, since the days of universal repose set in, and the townships required no protection, an arrangement was made with the Bhumias of Mewar, in which the crown, foregoing its claim of quit-rent, has obtained their services in the garrisons and frontier stations of j^lice at a very slight pecuniary sacrifice. Such are the rights and privileges derived from the ryot cultivator alone. The Rana may dispossess the chiefs of Radnor, he could not touch the rights emanating from the community ; and thus the descendants of a chieftain, who a few years before might have followed his sovereign at the hpad of one hundred cavaliers, would descend into the humble foot militia of a district. Thou sands are in this predicament : the Kanawats, Lunawats, Kum bhawats, and other clans, who, like the Celt, forget not their claims of birth in the distinctions of fortune, but assert their propinquity as " brothers in the nineteenth or thirtieth degree to the prince " on the throne. So sacred was the tenure derived from the ryot, that even monarchs held lands in hhum from their subjects, for an instance of which we are indebted to the great poetic historian of the last Hindu king. Chand relates, that when his sovereign, the Chauhan, had subjugated the kingdom of Anhilwara ^ from the Solanki, he returned to the nephew of the 1 See p. 195. 2 See Sketch of Feudal System, p. 170. 3 Nahrwala of D'Anville ; the Balhara sovereignty of the Arabian travellers of the eighth and ninth centuries. I visited the remains of this city on my last journey, and from original authorities shall give an account of this ancient emporium of commerce and literature. conquered prince several districts and seaports, and all the bhum held by the family. In short, the Rajput vaunts his aristocratic distinction derived from the land ; and opposes the title of ' Bhumia Raj,' or government of the soil, to the ' Bania Raj,' or commercial government, which he affixes as an epithet of con tempt to Jaipur : where " wealth accumulates and men decay."

In the great ' register of patents ' (jmtta bald) of Mewar we find a species of [498] bhum held by the greater vassals on par ticular crown lands ; whether this originated from inability of ceding entire townships to complete the estate to the rank of the incumbent, or whether it was merely in confirmation of the grant of the commune, could not be ascertained. The benefit from this bhum is only pecuniary, and the title is ' bhum, rakhwali ' ^ or land [in return for] ' preservation.' Strange to say, the crown itself holds ' bhum, rakhwali ' on its own fiscal demesnes consisting of small portions in each village, to the amount of ten thousand rupees in a district of thirty or forty townships. This species, however, is so incongruous that we can only state it does exist : we should vainly seek the cause for such apparent absurdity, for since society has been, unhinged, the oracles are mute to much of antiquated custom.

Occupiers' Rights in the Land

We shall close these remarks with some illustrative traditions and yet existing customs, to substantiate the ryot's right in the soil of Mewar, After one of those convulsions described in the annals, the prince had gone to espouse the daughter of the Raja of Mandor, the (then) capital of Marwar. It is customary at the moment of hathleva, or the junction of hands, that any request preferred by the bridegroom to the father of the bride should meet compliance, a usage which has yielded many fatal results ; and the Rana had been prompted on this occasion to demand a body of ten thousand Jat cultivators to repeople the deserted fisc of Mewar. An assent was given to the unprecedented demand, but when the inhabitants were thus despotically called on to migrate, they denied the power and refused. " Shall we," said they, ' abandon the lands of our inheritance (bapota), the property of our children, to accompany a stranger into a foreign land, there to labour for him ? Kill us you may, but never shall we relinquish our inalienable rights." The Mandor prince, who had trusted to this reply, deemed himself 1 Salvamenta of fche European system. exonerated from his promise, and secured from the loss of so many subjects : but he was deceived. The Rana held out to them the enjoyment of the proprietary rights escheated to the crown in his country, with the lands left without occupants by the sword, and to all, increase of property. When equal and absolute power was thus conferred, they no longer hesitated to exchange the arid soil of Marwar for the garden of Rajwara ; and the descendants of these Jats still occupy the fiats watered by the Berach and Banas [499].

In those districts which afforded protection from innovation, the proprietary right of the ryot will be found in full force ; of this the populous and extensive district of Jahazpur, consisting of one hundred and six townships, affords a good specimen. There are but two pieces of land throughout the whole of this tract the property of the crown, and these were obtained by force during the occupancy of Zalim Singh of Kotah. The right thus unjustly acquired was, from the conscientiousness of the Rana's civil governor, on the point of being annulled by sale and reversion, when the court interfered to maintain its proprietary right to the tanks of Loharia and Itaunda, and the lands which they irrigate, now the bhum of the Rana.1 This will serve as an illustration how bhum may be acquired, and the annals of Kotah will exhibit, unhappily for the ryots of that country, the almost total annihilation of their rights, by the same summary process which originally attached liOharia to the fisc. The power of alienation being thus proved, it would be super fluous to insist further on the proprietary right of the cultivator of the soil.

Proprietary Rights in Land

Besides the ability to alienate as demonstrated, all the overt symbols which mark the proprietary right in other countries are to be found in Mewar ; that of entire conveyance by sale, or temporary by mortgage ; and numerous instances could be adduced, especially of the latter. The fertile lands of Horla, along the banks of the Khari, are almost all mortgaged, and the registers of these transactions form two

1 The author has to acknowledge with regret that he was the cause of the Mina proprietors not re-obtaining theii" bapota : this arose, partly from ignorance at the time, partly from the individual claimants being dead, and more than all, from the representation that the intended sale originated in a bribe to Sadaram the governor, which, however, was not the case. considerable volumes, in which great variety of deeds may be discovered : one extended for one hundred and one years ; 1 when redemption was to follow, without regard to interest on the one hand, or the benefits from the land on the other, but merely by repayment of the sum borrowed. To maintain the interest during abeyance, it is generally stipulated that a certain portion a fourth, a a share so small as to be valued only as a mark of proprietary recognition.2 The mortgagees were chiefly of the commercial classes of the large frontier towns ; in [500] many cases the proprietor continues to cultivate for another the lands His ancestor mortgaged four or five generations ago, nor does he deem his right at all impaired. A plan had been sketched to raise money to redeem these mortgages, from whose complex operation the revenue was sure to suffer. No length of time or absence can affect the claim to the bapota, and so sacred is the right of absentees, that land will lay sterile and unproductive from the penalty which Manu denounces on all who interfere with their neighbour's rights : " for unless there be an especial agreement between the owner of the land and the seed, the fruits belong clearly to the land-owner " ; even " if seed conveyed by water or by wind should germinate, the plant belongs to the land owner, the mere sower takes not the fruit." 3 Even crime and the extreme sentence of the law will not alter succession to property, either to the military or cultivating vassal ; and the old Kentish adage, probably introduced by the Jats from Scandinavia, who under Hengist established that kingdom of the heptarchy, namely : The father to the bough, And the son to the plough 1 Claims to the bapota appear to be maintainable if not alienated longer than one hundred and one years ; and undisturbed possession (no matter how obtained) for the same period appears to confer this right. The miras of Khandesh appears to have been on the same footing. See Mr. Elphin stone's Report, October 25, 1819, ed. 1872, p. 17 f., quoted in BG, xii. 266. [The word mirds means " inherited estate,' the right of disposal of which rests with the holder. The Jats certainly did not bring the custom to Kent.] 2 The sawmy begum of the peninsula in Fifth Report, pp. 356-57 ; correctly sivami bhoga, ' lord's rent,' in Sanskrit. 3 Manu, Laws, ix. 52-54, on the Servile Classes. [Buhler's version differs, but the meaning is practically the same as that of the text.] is practically understood by the Jats and Bhumias 1 of Mewar, whose treason is not deemed hereditary, nor a chain of noble acts destroyed because a false link was thrown out. We speak of the the cultivator cannot aspire to so dignified a crime as treason.

Village Officials : the Patel

The officers of the townships are the same as have been so often described, and are already too familiar to those interested in the subject to require illustration. From the Patel, the Cromwell of each township, to the village gossip, the ascetic Sannyasi, each deems his office, and the land he holds in virtue thereof in perpetuity free of rent to the State, except a small triennial quit-rent,2 and the liability, like every other branch of the State, to two war taxes.3 Opinions are various as to the origin and attributes of the Patel, the most important personage in village sway, whose office is by many deemed foreign to the pure Hindu system, and to which language even his title is deemed alien. But there is no doubt that both office and title are of ancient growth, and even etymological rule proves the Patel to be head (pati) of the com munity.4 The office of Patel [.501] of Mewar was originally elective ; he was ' primus inter pares,' the constituted attorney or representative of the commune, and as the medium between the cultivator and the government, enjoyed benefits from both. Besides his bapota, and the serano, or one-fortieth of all produce from the ryot, he had a remission of a third or fourth of the rent from such extra lands as he might cultivate in addition to his patrimony. Such was the Patel, the link connecting the peasant with the government, ere predatory war subverted all order :

1 Patel. 2 Patel barar. 3 The Gharginti barar, and Kharlakar, or wood and forage, explained in the Feudal System. 4 In copper-plate grants dug from the ruins of the ancient Ujjain (pre sented to the Royal Asiatic Society), the prince's patents (patta) conferring gifts are addressed to the Patta-silas and Ryots. I never heard an etymo logy of this word, but imagine it to be from patta, ' grant,' or ' patent,' and sila, which means a nail, or sharp instrument; [? sila, the stone on which the grant is engraved] ; metaphorically, that which bmds or unites these patents ; all, however, having pati, or chief, as the basis (see Trans actions of the Royal Asiatic Society, vol. i. p. 237). {Pati, ' chief,' has no connexion with patta, ' a grant,' the latter being the origin of patel. For the position of the Patel see Baden-Powell, The Indian Village Community, 10 ff. ; Malcolm, Memoir of Central India, 2nd ed. ii. 14 ff.] but as rapine increased, so did his authority. He became the plenipotentiary of the community, the security for the contribu tion imposed, and often the hostage for its payment, remaining in the camp of the predatory hordes till they were paid off. He gladly undertook the liquidation of such contributions as these perpetual invaders imposed. To indemnify himself, a schedule was formed of the share of each ryot, and mortgage of land, and sequestration of personal effects followed till his avarice was satisfied. Who dared complain against a Patel, the intimate of Pathan and Mahratta commanders, his adopted patrons ? He thus became the master of his fellow-citizens ; and, as power corrupts all men, their tyrant instead of their mediator. It was a system necessarily involving its own decay ; for a while glutted with plenty, but failing with the supply, and ending in desolation, exile, and death. Nothing was left to prey on but the despoiled carcase ; yet when peace returned, and in its train the exile ryot to reclaim the bapota, the vampire Patel was resuscitated, and evinced the same ardour for supremacy, and the same cupidity which had so materially aided to convert the fertile Mewar to a desert. The Patel accordingly proved one of the chief obstacles to returning prosperity ; and the attempt to reduce this corrupted middle-man to his original station in society was both difficult and hazardous, from the support they met in the corrupt officers at court, and other influences ' behind the curtain.' A system of renting the crown lands deemed the most expedient to advance prosperity, it was incumbent to find a remedy for this evil.

The mere name of some of these petty tyrants inspired such terror as to check all desire of return to the country ; but the origin of the institution of the office and its abuses being ascertained, it was imperative, though difficult, to restore the one and banish the other. The original elective right in many townships was therefore returned to the ryot, who nominated new Patels [502], his choice being confirmed by the Rana, in whose presence in vestiture was performed by binding a turban on the elected, for which he presented his nazar. Traces of the sale of these offices in past times were observable ; and it was deemed of primary importance to avoid all such channels for corruption, in order that the ryot's election should meet with no obstacle. That the plan was beneficial there could be no doubt ; that the benefit would be permanent, depended, unfortunately, on circumstances which those most anxious had not the means to control : for it must be recollected, that although " personal aid and advice might be given when asked," all internal interference was by treaty strictly, and most justly, prohibited. After a few remarks on the mode of levying the crown-rents, we shall conclude the subject of village economy in Mewar, and proceed to close this too extended chapter with the results of four years of peace and the consequent improved prosperity.

Modes of Collecting Rents

There are two methods of levying kankut and batai, for on sugar-cane, poppy, oil, hemp, tobacco, cotton, indigo, and garden stuffs, a money payment is fixed, varying from two to six rupees per bigha. The kankut 1 is a conjectural assessment of the standing crop, by the united judgement of the officers of government, the Patel, the Patwari, or registrar, and the owner of the field. The accuracy with which an accustomed eye will determine the quantity of grain on a given surface is surprising : but should the owner deem the estimate overrated, he can insist on batai, or division of the corn after it is threshed ; the most ancient and only infallible mode by which the dues either of the government or the husbandman can be ascertained. In the batai system the share of the government varies from one-third to two-fifths of the spring harvest, as wheat and barley ; and sometimes even half, which is the invariable proportion of the autumnal crops. In either case, kankut or batai, when the shares are appropriated, those of the crown may be commuted to a money payment at the average rate of the market. The kut is the most liable to corruption. The ryot bribes the collector, who will underrate the crop ; and when he betrays his duty, the shahnah, or watchman, is not likely to be honest : and as the makai, or Indian corn, the grand autumnal crop of Mewar, is eaten green, the crown may be defrauded of half its dues. The system is one of uncertainty, from which eventually the ryot derives no advantage, though it [.503] fosters the cupidity of patels and collectors ; but there was a barar, or tax, introduced to make up for this deficiency, which was in proportion to the quantity cultivated, and its amount at the mercy of the officers. Thus the ryot went to work with a mill-stone round his neck ; instead of the exhilarating reflection that every hour's additional 1 [Kan, ' grain,' kut, ' valuation,' batai from batand, ' to divide.'] labour was his own, he saw merely the advantage of these harpies, and contented himself with raising a scanty subsistence in a slovenly and indolent manner, by which he forfeited the ancient reputation of the Jat cultivator of Mewar.

Improvement in the Condition of the People

Notwithstanding these and various other drawbacks to the prosperity of the country, in an impoverished court, avaricious and corrupt officers, dis contented Patels, and bad seasons, yet the final report in May 1822 could not but be gratifying when contrasted with that of February 1818. In order to ascertain the progressive improve ment, a census had been made at the end of 1821, of the three central fiscal districts 1 watered by the Berach and Banas. As a specimen of the whole, we may take the lappa or subdivision of Sahara. Of its twenty-seven villages, six were inhabited in 1818, the number of families being three hundred and sixty-nine, three fourths of whom belonged to the resumed town of Amli. In 1821 nine hundred and twenty-six families were reported, and every village of the twenty-seven was occupied, so that population had almost trebled. The number of ploughs was more than trebled, and cultivation quadrupled ; and though this, from the causes described, was not above one-third of what real industry might have effected, the contrast was abundantly cheering. The same ratio of prosperity applied to the entire crown demesne of Mewar. By the recovery of Kumbhalmer, Raepur, Rajnagar, and Sadri Kanera from the Mahrattas ; of Jahazpur from Kotah ; of the usurpations of the nobles ; together with the resumption of all the estates of the females of his family, a task at once difficult and delicate ; 2 and by the subjugation of the mountain districts of Merwara, a thousand towns and villages were united to form the fiscal demesne of the Rana, composing twenty-four districts of various magnitudes, divided, as in ancient times; and with the primitive [504] appellations, into portions tantamount to the

1 Mui, Barak, and Kapasan. 2 To effect this, indispensable alike for unity of government and the establishment of a police, the individual statements of their holders were taken for the revenues they had derived from them, and money payments three times the amount were adjudged to them. They were gainers by this arrangement, and were soon loaded with jewels and ornaments, but the numerous train of harpies who cheated them and abused the poor ryot were eternally at work to defeat all such beneficial schemes ; and the counteraction of the intrigues was painful and disgusting. tithings and hundreds of England, the division from time im memorial amongst the Hindus.1 From these and the commercial duties 2 a revenue was derived sufficient for the comforts, and even the dignities of the prince and his court, and promising an annual increase in the ratio of good government : but profusion scattered all that industry and ingenuity could collect ; the artificial wants of the prince perpetuated the real necessities of the peasant, and this, it is to be feared, will continue till the present generation shall sleep with their forefathers.

Mines and Minerals

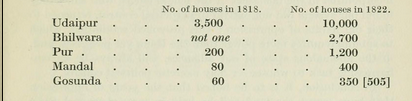

There are sources of wealth in Mewar yet untouched, and to which her princes owe much of their power. The tin mines of Jawara and Dariba alone, little more than half a century ago, yielded above three lakhs annually ; 3 1 Manu [Larvs, vii. 119] ordains the division into tens, hundreds, and thousands. 2 Farmed for the ensuing three years, from 1822, for seven lakhs of rupees. 3 In S. 1816, Jawara yielded Rs. 222,000 and Dariba Rs. 80,000. The tin of these mines contains a portion of silver. [What the Author calls the tin mines are probably the lead and zinc mines at Jawar, 16 miles south of Udaipur city. They seem now to be exhausted, and search might be made for other untouched pockets of ore. Those at Dariba, which formerly yielded a considerable revenue, have long been closed (Erskine ii. A. 53).] besides rich copper mines in various parts. From such f beyond a doubt, much of the wealth of Mewar was extracted, but the miners are now dead, and the mines filled with water. An attempt was made to work them, but it was so unprofitable that the design was soon abandoned. Nothing will better exemplify the progress of prosperity than the comparative population of some of the chief towns before, and after, four years of peace :

The Feudal Lands

The feudal lands, which were then double the fiscal, did not exhibit the like improvement, the merchant and cultivator residing thereon not having the same certainty of reaping the fruits of their industry ; still great amelioration took place, and few were so blind as not to see their account in it.1 The earnestness with which many requested the Agent to back their expressed intentions with his guarantee to their communities of the same measure of justice and protection as the fiscal tenants enjoyed was proof that they well understood the benefits of reciprocal confidence ; but this could not be tendered without danger. Before the Agent left the country he greatly withdrew from active interference, it being his constant, as it was his last impressive lesson, that they should rely upon them selves if they desired to retain a shadow of independence. To give an idea of the improved police, insurance which has been described as amounting to eight per cent in a space of twenty-five miles became almost nominal, or one-fourth of a rupee per cent from one frontier to the other. It would, however, have been quite Utopian to have expected that the lawless tribes would remain in that stupid subordination which the unexampled state

1 There are between two and three thousand towns, villages, and hamlets, besides the fiscal land of Mewar ; but the tribiite of the British Government is derived only from the fiscal ; it would have been impossible to collect from the feudal lands, which are burthened with service, and form the army of the State. of society imposed for a time (as described in the opening of these transactions), when they found that real restraints did not follow imaginary terrors. Had the wild tribes been under the sole influence of British power, nothing would have been so simple as effectually, not only to control, but to conciliate and improve them ; for it is a mortifying truth, that the more remote from civilization, the more tractable and easy was the object to manage, more especially the Bhil.1 But these children of nature were incorporated in the demesnes of the feudal chiefs, who when they found our system did not extend to perpetual control, returned to their old habits of oppression : this provoked retaliation, which to subdue requires more power than the Rana yet possesses, and, in the anomalous state of our alliances, will always be an em barrassing task to whosoever may exercise political control. In conclusion, it is to be hoped that the years of oppression that have swept the land will be held in remembrance by the protecting power, and that neither petulance nor indolence will lessen the benevolence which restored life to Mewar. or mar the picture of comparative happiness it created. 1 Sir John Malcolm's wise and philanthropic measures for the reclama tion of this race in Malwa will sup2:)ort my assertions [Memoir of Central India, 2nd ed. i. 516 ff., ii. 179 ff.]