Mob violence/ lynchings: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Incidents

2014-June 2017

Jun 27 2017: The Times of India

A spurt in lynching cases has exposed the absence of law enforcement to punish the guilty. The only known instance of conviction in a mob justice case in recent years was of ex-MP Anand Mohan and two MLAs who got life in 2007 for lynching of Gopalganj DM Krishnaiah in 1994.

2017-18: How fake forwards create killer mobs

June 18, 2018: The Times of India

From: June 18, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic:

2017-18: How fake forwards create killer mobs

Doctored content, fake alerts and sensationalised messages are all it takes to fuel mass suspicion of strangers and propel mobs to brutally attack innocents. These forwards, of blood-thirsty gangs of kidnappers, thieves or dacoits, spread mainly via WhatsApp and Facebook, use morphed images, even from other countries, to create a fear psychosis

2018

Why hoaxes behind lynchings beat cops, June 18, 2018: The Times of India

Reporting by Petlee Peter in Bengaluru, Mahesh Buddi in Hyderabad, Debabrata Mohapatra in Bhubaneswar, B Sridhar in Jamshedpur, Mohammed Akhef in Aurangabad, Shanmugha Sundaram J in Vellore

A slew of protests took place across the country after 10 people were killed in two months by mobs reacting to rumours of kidnappers grabbing children, but the flow of fake messages and morphed videos has hardly been impacted. Though police round up people, sometimes in the hundreds, the fight against fake messages stoking real fears is barely begun.

The Bengaluru police is no stranger to countering fake messages warning of kidnappers or terror plots. Every day, a team of 14 officers monitors Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and WhatsApp. Tracking has worked at times — during the Cauvery riots a few years ago, social media was used to counter rumours.

But their efforts couldn’t save a 26-year-old from Rajasthan last month in the heart of Bengaluru. Kalu Ram was beaten to death by locals who fell prey to WhatsApp messages about abductors. In fact, 90 people were assaulted by mobs over child-abduction rumours in April and May in Karnataka.

An officer says there’s no way to trace the origin of such messages on WhatsApp. Instead, they go person to person, finding out who forwarded it. “We counter such messages with our own on our WhatsApp groups,” said the officer. An early instances of WhatsApp rumours spiralling out of control was in Bengaluru in 2012 when fear of attacks led to an exodus of north-easterners.

“We can only ask people to refrain from believing rumours,” says Odisha DGP Rajendra Prasad Sharma. About 25 people, mostly labourers or beggars from neighbouring states, have been attacked across Odisha in the last two months on suspicion of being kidnappers. There were no deaths but police are trying to prevent attacks, counter rumours, says Sharma.

There seems to be only so much the police believes it can do to stop the rumours. In Maharashtra’s Aurangabad, staff have been asked to join as many WhatsApp groups as possible to track fake messages and also undertake patrolling to alert residents. Further, pollice decided to block for a period internet services for seven hours daily in the rural areas to curb the spread of rumours.

Awareness campaigns are on in Telangana, where three people were lynched in separate incidents in May on suspicion of being kidnappers from Bihar and UP. Hyderabad cybercrime cops arrested a private employee for spreading rumours via WhatsApp while 14 people in the city were heldlast month for attacks on transgenders over rumours of cross-dressing kidnappers.

Since April 22, at least five have been killed in similar rumour-based lynchings in Tamil Nadu’s northern districts. Vellore SP P Pakalavan told TOI that rumour-mongers would be booked under the Goondas Act.

Mass arrests and booking the accused under multiple sections are how police tackle mob violence. Police arrested 11, and booked 400 villagers for murder, attempt to murder and assault in Aurangabad, where two tribals were lynched and six injured in May. Many of the fake messages are forwarded in areas where abduction is a very real fear among locals. “The rumours were around for a month,” said a policeman in Aurangabad’s Vaijapur, adding that alarmed locals were staying up on night vigils bearing torches and sticks. But the police, though in the know about the messages, could do little to prevent the murderous attack on the two tribal men.

In Jharkhand, more than 100 people have been accused in three lynching cases in which 10 innocent people were killed over 10 days in May 2017 in East Singhbhum and adjoining Seraikela-Kharswan districts. All three cases are at various stages of trial. After the lynchings over the last two months, East Singhbhum police have launched a fresh drive to counter rumours. “We’ve appealed to people to inform police if they see such rumours on social media,” said a DSP in Jharkhand.

Legal position

How are lynch mobs punished?

There is no single ‘special’ law to bring those accused of lynching incidents to book. Lynching is so unique a category of crime that it is a cumbersome process for police and the courts as well. When a mob renders kangaroo justice, it is almost impossible to identify the members and fasten culpability individually for the purpose of a fair trial.

In the absence of a special law, how are lynch mobs punished?

Jurists say police must assemble a bouquet of charges to hold the case together. Lynching being no ordinary murder (Sec 302), police must also invoke other criminal charges such as common intention (Sec 34) and being present and abetting an offence punishable with death (Sec 114).

“While murder, read with common intention and abetment, forms the bedrock, police can invoke conspiracy charges against those who orchestrated the lynching or invoke IT Act 66A against those who created the content and spread it on social media,” said former additional solicitor-general of India P Wilson.

Hence, for a watertight lynching case, there must be at least five criminal elements woven into it.

Former special public prosecutor for Tamil Nadu’s human rights court V Kannadasan says leaving out the ‘conspiracy’ portion helps the prosecution, since they need not piece together every evidence to prove that there indeed was a meeting of minds that led to the mob being formed followed by the murder. Most lynchings are not premeditated.

The charge of common intention, on the contrary, treats whoever commits the crime on a par with those standing guard. “Mere presence of an accused at the place of occurrence is enough to convict him. Police need not prove with evidence individual roles played by each mobster. Any number can be included,” he said, adding that such an approach works effectively in cases of lynching.

To show conspiracy (Sec 120B), a meeting of minds has to be proved, and visual evidence is a must to prove involvement of offenders. For common intent, video evidence plays a crucial role, as police can follow procedure to conclusively prove that the offender was present at the scene of occurrence. They only need the video clipping or photograph certified under the Evidence Act, vouchsafing that the video/photo was taken by X and downloaded by X.

Tamil Nadu witnessed five lynchings in the past two months. The genesis was WhatsApp forwards warning villagers that a group of ‘child lifters’ had descended on their areas and that scores of kids had already gone missing. Such was the ire evoked by the rumour that a mob in Pulicat near Chennai gouged out a stranger’s eyes and hanged him from a bridge.

The same rumour claimed lives of two in Assam within a month.In the police net now are those who forwarded the messages and who are seen in video clippings kicking and punching the Pulicat victim. “Though those handling platforms like WhatsApp have a responsibility, they cannot be treated on a par with the actual attackers,” believes advocate and deputy editor-in-chief of Madras Law Journal V Lakshminarayanan. “Fact remains though that had he not forwarded the rumour, the tragedy would not have occurred at all. To that extent, he, too, contributes to the tragic crime.”

Supreme Court’s July 2018 judgement

Bench orders Centre and States to implement measures and file compliance reports within the next four weeks.

The Supreme Court condemned recent incidents of lynching and mob violence against Dalits and minority community members as "horrendous acts of mobocracy", and asked Parliament to pass law establishing lynching as a separate offence with punishment.

A three-judge Bench led by Chief Justice of India Dipak Misra held that it was the obligation of the State to protect citizens and ensure that the "pluralistic social fabric" of the country holds against mob violence.

The judgment authored by Chief Justice Misra for the Bench, also comprising Justices A.M. Khanwilkar and D.Y. Chandrachud, said such law should be effective enough to instill a sense of fear in the perpetrators.

Numbness of people 'shocking'

The court said the growing numbness of the ordinary Indian to the frequent incidents of lynchings happening right before his eyes in a society based on rule of law is shocking. The government should see the judgment as a "clarion call" in a time of exigency and work towards strengthening the social order.

It was also the obligation of the Centre and the States to ensure that "nobody takes the law into his hands nor become a law into himself", the court said. It directed several preventive, remedial and punitive measures to deal with lynching and mob violence.

The court ordered the Centre and the States to implement the measures and file compliance reports within the next four weeks.

In the last hearing of the case, the court had classified lynchings as sheer "mob violence". It had said compensation for victims should not be determined solely on the basis of their religion, caste, etc, but on the basis of the extent of injury caused as "anyone can be a victim" of such a crime.

Chief Justice Misra said the States could not give even the "remotest chance" to let lynchings happen.

Contempt petition

The judgment came in a contempt petition filed by activist Tehseen Poonawalla. It said that despite the Supreme Court order to the States to prevent lynchings and violence by cow vigilantes, the crime continued with impunity.

"Despite your order to the States to appoint nodal officers to prevent such incidents, there was a lynching and death just 60 km away from Delhi just recently," senior advocate Indira Jaising had submitted.

Ms. Jaising argued that the incidents of lynchings go "beyond the description of law and order... these crimes have a pattern and a motive. For instance, all these instances happen on highways. This court had asked the States to patrol the highways".

The lynchings were "targeted violence" against particular religion, caste, an thus, in violation of the constitutional guarantees under Article 15 of the Constitution. Article 15 protected from discrimination on the basis of religion, caste, sex, gender, etc., Ms. Jaising said.

Chief Justice Misra had even asked the Centre to frame a scheme under Article 256 to give directions to the States to prevent/control the instances and maintain law and order, but Additional Solicitor General P.S. Narasimha disagreed, saying such a scheme was unnecessary.

Supreme Court’s Oct 2018 guidelines

The Supreme Court issued comprehensive guidelines to control mob violence and held that any person or organisation, giving a call for such action, would be liable to pay compensation for loss of life or damage to public and private property, besides facing criminal proceedings.

“This court has time and time again underscored the supremacy of law and that one must not forget that administration of law can only be done by law-enforcing agencies recognised by law. Nobody has the right to become a self-appointed guardian of the law and forcibly administer his or her own interpretation of the law on others, especially not

with violent means. Mob violence runs against the very core of our established legal principles since it signals chaos and lawlessness and the state has a duty to protect its citizens against the illegal and reprehensible acts of such groups,” a bench headed by Chief Justice Dipak Misra said.

It directed state governments to set up Rapid Response Teams, preferably district-wise, which could be quickly mobilised to respond to acts of mob violence. It said these teams can also be stationed around vulnerable cultural establishments and also asked the states to set up special helplines to deal with such instances.

Person in mob need not assault to be convicted: SC

Nov 6, 2023: The Times of India

The Supreme Court has clarified that a person can be convicted for being part of an unlawful mob even if they did not personally assault anyone. The court referenced a 1964 case that stated if an offence was committed by any member of an unlawful assembly in pursuit of their common goal, then every member of the assembly is guilty. The court emphasized that it is not necessary for every person in the assembly to play an active role, but they must be aware of the common object and be part of the assembly.

NEW DELHI: The Supreme Court has reiterated that it is not necessary that a person who is part of an unlawful mob must have actually assaulted someone for being convicted for the offence, a point of law that was settled way back in 1964.

In the 'Masalti vs State of UP' case in 1964, a constitution bench had said Section 149 of IPC made it clear that if an offence was committed by any member of an unlawful assembly in prosecution of the common object of that assembly, or such as the members of that assembly knew to be likely to be committed in prosecution of that object, every person who, at the time of the committing of that offence, was a member of the same assembly was guilty of that offence.

Relying on the 1964 verdict, a bench of Justices B R Gavai, B V Nagarathna and Prashant Kumar Mishra said, "It could thus clearly be seen that the constitution bench has held that it is not necessary that every person constituting an unlawful assembly must play an active role for convicting him with the aid of Section 149 of IPC. What has to be established by the prosecution is that a person has to be a member of an unlawful assembly, i.e. he has to be one of the persons constituting the assembly and that he had entertained the common object, along with the other members of the assembly."

On October 12, another SC bench had passed a similar order on unlawful assembly and had said that a person could be convicted for an offence committed by a mob only if he shared a common object of unlawful assembly and he was aware of the offences likely to be committed to achieve the said common object.

"This provision (Section 149) does not create a separate offence but only declares vicarious liability of all members of unlawful assembly for acts done in common object. Thus, in order to attract Section 149 of the Code, it must be shown by the prosecution that the incriminating act was done to accomplish the common object by such unlawful assembly. It must be within the knowledge of the other members as one likely to be committed in furtherance of the common object. Even if no overt act is imputed to the accused, the presence of the accused as part of the unlawful assembly is sufficient for conviction. The inference of a common object has to be drawn from various factors such as the weapons with which the members were armed, their movements, the acts of violence committed by them and the end result," the bench had said.

"To convict a person under Section 149 IPC, prosecution has to establish with the help of evidence that firstly, appellants shared a common object and were part of unlawful assembly, and secondly, it has to prove that they were aware of the offences likely to be committed to achieve the said common object," the bench had said.

The response of the state, the courts

New laws, strict actions

Sep 7, 2019: The Times of India

From: Sep 9, 2019: The Times of India

From: Sep 9, 2019: The Times of India

Inputs by Ramashankar in Patna, Mohammed Akhef in Aurangabad, Keshav Agrawal in Pilibhit, Nazar Abbas in Rampur, Pranjal Baruah in Guwahati, Pinak Priya Bhattacharya in Jalpaiguri, Somreet Bhattacharya & Anam Ajmal in Delhi, Sandeep Rai in Meerut

From: Sep 7, 2019: The Times of India

From: Sep 7, 2019: The Times of India

From: Sep 7, 2019: The Times of India

From: Sep 7, 2019: The Times of India

A woman walking her 4-yearold grandson in Loni, Delhi-UP border, was attacked on August 28 by a mob that accused her of kidnapping the little boy. The hapless grandmother was somehow rescued by police and the attackers were held. The mob said the child’s complexion “did not match” hers.

The very next day in Ghaziabad, two strangers standing next to each other on the roadside were beaten up for “looking like child-lifters”.

In the last two years, the deadly routine has become familiar across the country. In various languages — from Gujarati to Tamil, Bengali and Hindi — messages of “kidnappers” with photoshopped and morphed images, or fake videos, are furiously forwarded on WhatsApp groups, weaponizing frenzied locals to attack anyone who in their eyes fits the bill.

This year the rumours “surfaced with vengeance” in July, reported AltNews, a fact-check website. Among the many videos was one of a 2017 prison riot in Brazil shared as kidnapping gangs on the prowl around schools in Madhya Pradesh. These videos, a Delhi police officer said, are “a form of cyber warfare trending now for five to six years”. The videos initially appear on fake profiles created for the purpose on Facebook and Twitter.

‘CYBER WARFARE’, STRICT LAWS

Police suspect the videos are part of a “larger campaign” which includes political fake news in circulation. Fake video “factories”, the DCP-level officer, said, are spread across the world, from the US to Europe and west Asia, apart from neighbouring nations. There is an uptick ahead of the festive season that includes vacations.

The rash of 30 attacks over abduction rumours last year, alongside the “cow lynching” cases led the Supreme Court to issue guidelines in July 2018 for the Centre and states to decide on strong punitive and remedial measures, terming the crimes “horrendous act of mobocracy”.

A year on, the assaults continue — more brazen and frequent than ever, reminiscent of medieval barbarism. This July, the apex court issued notices to the Centre, National Human Right Commission and various states on implementation of the guidelines, which included district-wise monitoring against all forms of vigilantism, special courts, fast-tracking of cases, sixmonth trials of those accused and penalty for police and district administrations that failed their duty. Manipur and Rajasthan have laws in place. Bengal will be the third state to enact a law in the current session making lynching an offence punishable with a life-term and fine of Rs 5 lakh. The West Bengal (Prevention of) Lynching Bill, 2019, makes conspiracy and rumour mongering offences that would attract prison time.

When 58 mob attacks were reported in UP in August alone, police threatened rumour-mongers with the stringent National Security Act. Victims included an elderly couple, an NGO volunteer, labourers, health officials. DGP O P Singh said over 80 have been arrested for spreading rumours about child theft.

In August’s last weekend, nine attacks on suspicion of child-lifting were reported from across the country in 48 hours, six from UP and three from Jharkhand, making both police and the general public jittery. In August alone, around 150 attacks have been reported across states.

WARY POLICE IN ACTION MODE

Having a law is need of the hour, but policemen — who the SC expects to ensure “dispersal of mobs” that can “lynch in the garb of vigilantism” — are wary. In Bihar, for instance, that saw at least 30 mob violence incidents in the last four months and more than 12 people lynched, cops concede they’re overwhelmed by the sheer spread of the rumours. No one is spared. In a bizarre case in Samastipur and Rohtas, central government officers were attacked in two separate incidents stemming from the similar rumours. Railway engineers and geological surveyors from Manipur and Kolkata were thrashed while on duty on projects. No amount of flashing ID cards appeased the rampaging mobs. Police rescued them but were themselves rattled by the ferocity of the men baying for blood.

Bihar police has repeated warnings that offenders will be booked under the harsh Crime Control Act. Many officers have said that many times the mentally unstable, vendors and beggars were soft targets.

“More and more people indulge in such crimes and fall prey to rumours also because they are not aware of laws,” Bihar ADG Jitendra Kumar said. “SHOs and officers have been asked to launch campaigns in remote areas from where the bulk of incidents have been reported.”

Police and district administrations in several states have since last year made their presence felt on social media, using Facebook Live and WhatsApp groups to monitor, track and act. In Delhi, Bengaluru and several cities and districts, police are part of residents group chats, tasked to track down those who share morphed messages. In the mofussils, they are using public address systems and have roped in village pradhans for the counter-offensive.

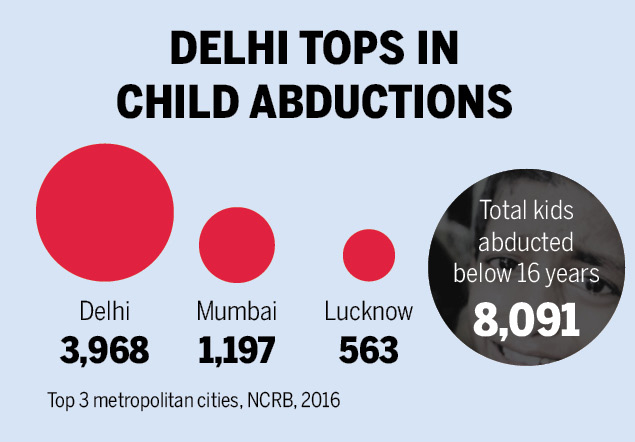

KIDNAPPINGS A REAL FEAR

Lynch attacks over abduction talk are a twisted reality. Missing children is a grave problem in India, and rumours play on very real fears. The women and child ministry’s website notes a child disappears in India every 10 minutes. As per the latest crime records data in public, over 63,000 children went missing in 2016; over 15,000 aged below 16 were abducted in just the 19 cities with populations of 2 million-plus. Delhi topped the list. The numbers are large even putting aside a chunk of cases where teenagers are presumed to not have been kidnapped per se.

Against this grim background, social workers suggested the powerful grip of rumours is also a result of people having little faith in police. Half the children kidnapped are never found. Fear is played upon. “A mob is ruthless... controlled by the person who controls the emotion: be it anger, fear or alienation,” said sociologist Shiv Visvanathan.

AWAITING JUSTICE

Far away in Assam, Gopalda Chandra Das is a broken man. Among the most gruesome incidents of the recent past, two young men from Guwahati, mistaken to be kidnappers, were beaten to death in Karbi Anglong by a savage gathering in 2018. They were educated, had jobs and spoke in Assamese, talking about their local parents and a wellknown school they had attended. But the crowd wouldn’t relent. “We are still awaiting justice for the death of my son and his friend,” said Das, the father of Nilotpal, a sound engineer and one of the two men who died that day. “We want exemplary punishment for the culprits so that such a horrific thing doesn’t happen to anyone.”

SC'S GUIDELINES

Sep 9, 2019: The Times of India

States to designate officer of SP rank as nodal officer in each district to prevent mob violence

Centre, states to broadcast, radio, TV and online messages warning that lynching and mob violence shall invite serious consequences

FIR must against persons spreading such fake/irresponsible messages, videos

Police, district administration's failure to comply with SC directions will be deemed deliberate negligence

States to draw up compensation scheme for lynching with provision for interim relief for victim(s)/next of kin within 30 days

Lynching cases to be tried by fast-track courts in each district and preferably concluded within 6 months

See also

Ahmedabad: Gulbarg Society killings, 2002

Communal clashes, riots, hate crimes: India

Kidnapping, 'child lifting': India

Mob violence/ lynchings: India