Mochi: Deccan

Contents |

Mochi

This article is an extract from THE CASTES AND TRIBES OF H. E. H. THE NIZAM'S DOMINIONS BY SYED SIRAJ UL HASSAN Of Merton College, Oxford, Trinity College, Dublin, and Middle Temple, London. One of the Judges of H. E. H. the Nizam's High Court of Judicature : Lately Director of Public Instruction. BOMBAY THE TlMES PRESS 1920 Indpaedia is an archive. It neither agrees nor disagrees |

Mochi, Machigar, Chambhar, Chammar, Samgar — an occu- pational caste of shoe-makers cobblers and leather workers, pro- bably of Maratha origin, but at the ' present "day distributed in varying numbers all over the Domirfions. The synonyms above given represent names by which the caste is known in different localities. In the Telugu Districts the members of the caste are called Mochis or Machigar, a name derived from the Canarese word "Machi" meaning shoes. Carnatic leather workers are designated as Samgars, or Chamgar, supposed to be derived from the Sanskrit 'Charmkar' while the shoe-makers of Maharashtra bear the name Chambhar, or Chammar, also a variant of the Sanskrit 'Charmkar. It should be borne in mind that the term Chafnmar is applied, in common speech, to all leather working classes including 'Dhors, who tan hides, and Madigas (Mangs), who make sandles; but these two are not to be confounded with Maratha Chambhars, or Mochis, who stand on a higher social level than either of them. Both the Dhor and the Madiga are ranked among the most unclean classes of Hindu society by reason of their skinning the carcasses of dead animals, tanning raw hides and eating carrion; but the Chambhar abstains from these, and works up leather already tanned; this circumstance has greatly helped to raise his social position, his touch not being regarded so impure as that of the Madiga or Dhor.

Origin

A tradition traces their origin to Rohidas or Harliya- noru, a great religious reformer who flourished at the end of the fourteenth century. Another legend, current among them, states that in the days of Basvanna there lived one Samgar Kalayya, who was a devout worshipper of the god Siva, and made shoes for his votaries. Pleased with his devotion the god bestowed upon him a boon by which a son was bom to him. Samgar Avaliya, as the boy was named, grew up and had three sons Bandeshat, Konduji and Tamaji, from whose descendants the present Samgar race is alleged to have sprung-.

Internal Structure

The main endogamous groups of the caste are Chambhar, Mochi, and Samgar corresponding to, and dwelling respectively in Maharashtra, Telingana and the Carnatic, the three great ethnic divisions of H. E. H. the Nizam's territory. Other sub-castes have arisen either by intermarriages between the members of different main groups^ or fcy the immigration of the members of one group into 'the locality of another. The sub-caste Are Samgar may sprve as an illustration. The members of the sub-caste are 'either descendants of Maratha Chambhars settled in early time in the Carnatic, or the result of intermarriages between Carnatic Samgars and Maratha Chambhars. The Telugu Mochis are divided into, Mochis and Jar Machigars, the latter mostly found in the Districts of Raichur and Gulbarga. The Maratha Chambhars have two sub-divisions, Chambhars and Vidur Chambhars, or the illegitimate offspring of the Chambhars. in the Carnatic the Samgar sub-caste is broken up into two hypergamous groups, Lingayit Samgars and Hindu Samgars, the former claiming social precedence over the latter from whom they take girls in marriage, but to whom they will not give their own daughters. Besides these there is a sub-caste named Boya Samgar, which is probably recruited from such Boyas or Bedars as have taken to shoe-making.

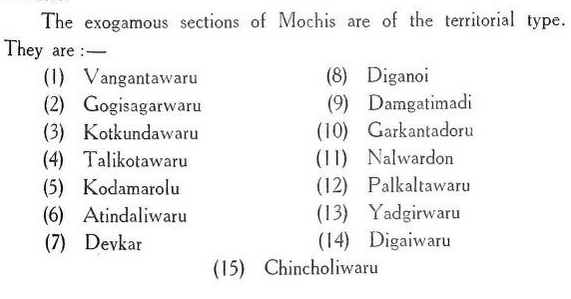

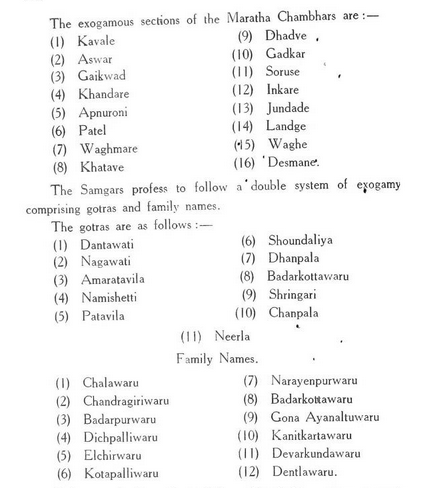

The sections of the caste appear, for the most part, to be borrow- ed from the higher castes and throw no light upon their original affinities.

It is not clearly understood how this double system serves to regulate their marriages.

As a rule the section name goes by the father's side. Marriages within the section are strictly forbidden, and to supplement this rule of exogamy, the same table of prohibited degrees is observed by Mochis as by other castes. The daughter of a mother's brother or father's sister may be married. A man may marry two sisters pro- vided the elder is married first. So also two brothers are allowed to marry two sisters.

Mochis admit into their caste members of other castes higher than themselves in social standing. No special ceremony is per- formed on thi?, occasion.

Marriage

Mochis marry their daughters either as infants, or after they Jiave attained the age of puberty. In the latter case sexual indiscretion before marriage is said to be tolerated and should a girl become pregnant she is allowed to marry, but her progeny are not admitted to the full rights of the caste. Sexual intercourse before puberty is allowed subject, however, to the performance of a ceremony at wiiich the tride's father entertains the bridegroom and his relations. Mochi girls ire not devoted to temples, nor dedicated to deities. When an adult girl goes, for the first time, to her hus- band's house, she is presented with zinc pots and her husband with a silver ring. A procession or 'Mirongi' is then formed to conduct the bridal pair to the bridegroom's house, the bridegroom riding on a bullock and the bride following him on foot. Polygamy is permitted and a man may have as many wives as he can afford to maintain.

The marriage ceremony in vogue varies with the locality, but scarcely differs frohi that of other castes of the same social status. At a 'Paiiawala', or betrothal ceremony in Maharashtra, the caste Panchas are regaled with drink, which is regarded as confirmation of the marriage. Previous to marriage, village deities including Sitala Devi (the small-pox goddess) and their patron saint Rohidas are invoked to bless the couple. The wedding takes place under a booth, at the bride's house, Kany)adan, or the formal gift of the bride to the bridegroom, forming the essential portion of the ceremony. The marriage of Telugu shoe-makers is an imitation of the ritual followed by other Telugu castes. On the fourth day after wedding, when the bridal pair circumambulate the ' Nagbali ' circle, the Telugu bridegroom holds in his hand a nut-cracker, or some implement of husbandry .

The Camatic ceremony includes the following rites : —

(1) 'Hogitoppa' or the fixing of an auspicious date for the cele- bration of the wedding.

(2) 'Devata Puja,' or the invocation of family and tutelary deities.

(3) 'Uditamba,' or the betrothal ceremony.

(4) 'Yaniarshani' : — the smearing of the bride and the bride- groom, previous to the wedding, with turtperic paste and oil.

(5) "Maniavana' : — which corresponds to the Telugu.Mailapoiu. Four vessels are arranged in a square and a raw cotton thread is wound round them. The bridal pair are seated inside and bathed.

(6) 'Matinoru' : — at which pearl water is sprinkled on the bridal pair.

(7) 'Pancha Kalasha' : — five brass 'vessels are arranged on the ground, and encircled with thread. The bride and the bridegroom are seated inside side by side and wedded by a Jangam officiating as priest. This ceremony includes 'Bashingam', 'tali,' ' kankanam ' and other rites of secondary importance.

(8) 'Akikal' : The wedded pair throw rice on each others heads.

(9) 'Bhum' : — Married women, whose husbands are living, are feasted in front of Panch Kalash.'

(10) Mirongi : — the bridal procession which conducts the pair to the bridegroom's house.

(11) Nagvely' : — Same as the Telugu Nagvely.

(12) 'Chagol' : — Bridal feast at which a goat is sacrificed. Among Canarese shoe-makers ' Teru ' or the bride price, varying in amount from Rs. 20 to Rs. 30, is paid by the bridegroom to the bride's father.

Widows may marry again. They are not restricted by any condition in their selection of a second husband, provided they strictly, conform to the rule of exogamy. The ceremony is very simple. On a dark night the bridegroom goes to the widow's house, ties pusti or Mangalsutra round her neck, makes her a present of clothes and bangles and early the next morning brings her home. A singular custom is observed when a bachelor marries a widow. Before going to the widow's house he is formally married to a 'ruchaki' or 'rui' plant (Calotropis gigantea) as if it were his bride. Divorce is per- mitted on the ground of the wife's unchastity or the husband's in- ability to maintain her. It is effected by sending the woman out of the house in the. presence of the caste council. If the wife claims divorce she is made to pay to her husband half the expenses incurred by him upon lier marriage. A woman having an intrigue with a man of a low caste is punished by expulsion from her own caste. Adultery with a man of her own caste or of a higher caste may be tolerated, the woman being punished, in the latter case, by a small fine, while in the former her paramour is compelled to pay her husband half the expenses of her marriage with him.

Inheritance

The Mochis follow the Hindu law of inheritance. In making a division of property the eldest son gets an extra share or 'Jethang'. According to custom, a sister's son, if made a son-in-law, is entitled to a share in his father-in-law's property, and in case the latter dies without issue, he inherits the whole property subject, how- ever, to the claims of his father-in-law's widows.

Religion

The Mochis are almost all Vibhutidharis, but Tirma- nidharis or Vaishnavaits are occasionally found among them. Most of the Carnatic shoemakers belong to the Lingayit sect. Special reverence is paid by, the members of the caste to their saintly ancestor Rohidas, to whom offerings of sweetmeat, wine and goats are made every Sunday. On the Dasera day goats are offered to the imple- ments of their trade. Pochamma and Ellamma are appeased when epidemics of cholera or small-pox break out. The Maratha Cham- bhars worship Mari Amma and Sitala. Previous to a marriage, they proceed on foot to the shrine of the goddess Sitala which they circum- ambulate five times. At the Divali festival, females adore Gauramma, the goddess who presides over married life. In the Carnatic, Jangams officiate as priests, but in other districts Brahmins are employed for religious and ceremonial purposes. These Brahmins bathe before they join their own community. A girl on attaining puberty is ceremonially unclean for five days. A child is named on the thirteenth day -after birth.

Funerals

The dead are buried, manied persons in a sitting posture with the face turned towards the north and the unmarried in a lying posture with the head to the south. Women, dying in pregnancy or in child birth, are burned. In the case of agnates mourning is observed ten days for adults and three days for children. On the third day after death a Jangam is called in to worship the mound erected over the remains of the dead person. Rice, curds, sweetmeats, flowers and roasted grain are offered, whereupon the chief mourner shaves his moustaches and becomes ceremta^;lly clean. On the Pitra Amawasya day, a feast is given to caste brethren in the name of the departed person. No regular sradha is celebrated by Mochis, either during mourning or on the anniversary day.

Social Status

In point of social standing the Mochis occupy a very low position in the Hindu caste system. No caste except the Madiga or Mala will eat food cooke'd by them, while they them- selves will take food from any Hindu caste, except the Jingar, Hajam, Dhobi, Panchadayi and the specially unclean castes of Dhors, Malas, Madigas and a few others. Their touch is held to be unclean and hence they are obliged to live on the outskirts of villages. Although the village barber occasionally shaves their head and the village washerman ^vashes their clothes, both have subsequently to undergo ablution owing to the defilement caused by the Mochi's touch. The Mochis eat pork, fowl, fish, mutton and even the flesh of animals dying a natural death, and indulge freely in strong drinks.

Occupation

The original occupation of the caste is to make shoes and other leather articles such as boxes, harness, saddles and portmanteaux. In their trade they use the hides of the cow, bullock, buffalo, deer, sheep and goat. They never dress freshly skinned hides of any of the animals except the deer, sheep and goat; but purchase them ready curried from Dhors or Madigas. The shoes worn at Hyderabad are generally of red leather. The patterns em- ployed vary and are sometimes ornamented with beautiful spangles am designs. Their price is from one to four rupees per pair. Boots of European pattern are also made by the members of the caste. Some of the Mochis cob old shoes, but the work of making sandals brings social disgrace and is relegated to Madigas or Mangs. The imple- ments of their trade are the 'rapi,' knife, 'kudti,' 'kurpi, 'avali' and kalibatta the last being used in shaping shoes.

The Mochis are one of the predial servants of the village and claim, from villagers, 'baluta' or allotments of corn at harvest time. A tew members of the caste have taken to cultivation and are engaged as farm and day labourers.