Mogēr

This article is an excerpt from Government Press, Madras |

Mogēr

The Mogērs are the Tulu-speaking fishermen of the South Canara district, who, for the most part, follow the aliya santāna law of inheritance (in the female line), though some who are settled in the northern part of the district speak Canarese, and follow the makkala santāna law (inheritance from father to son).

The Mogērs are largely engaged in sea-fishing, and are also employed in the Government fish-curing yards. On the occasion of an inspection of one of these yards at Mangalore, my eye caught sight of the saw of a sawfish (Pristis) hanging on the wall of the office. Enquiry elicited that it was used as a “threatening instrument” in the yard. The ticket-holders were Māppillas and Mogērs. I was informed that some of the Mogērs used the hated thattu vala or āchi vala (tapping net), in using which the sides of the boats are beaten with sticks, to drive the fish into the net. Those who object to this method of fishing maintain that the noise made with the sticks frightens away the shoals of mackerel and sardines. [66]A few years ago, the nets were cut to pieces, and thrown into the sea, as a protest against their employment. A free fight ensued, with the result that nineteen individuals were sentenced to a fine of fifty rupees, and three months’ imprisonment. In connection with my inspections of fisheries, the following quaint official report was submitted. “The Mogers about the town of Udipi are bound to supply the revenue and magisterial establishment of the town early in the morning every day a number of fishes strung to a piece of rope.

The custom was originated by a Tahsildar (Native revenue officer) about twenty years ago, when the Tahsildar wielded the powers of the magistrate and the revenue officer, and was more than a tyrant, if he so liked—when rich and poor would tremble at the name of an unscrupulous Tahsildar. The Tahsildar is divested of his magisterial powers, and to the law-abiding and punctual is not more harmful than the dormouse. But the custom continues, and the official, who, of all men, can afford to pay for what he eats, enjoys the privileges akin to those of the time of Louis XIV’s court, and the poor fisherman has to toil by night to supply the rich official’s table with a delicious dish about gratis.” A curious custom at Cannanore in Malabar may be incidentally referred to. Writing in 1873, Dr. Francis Day states44 that “at Cannanore, the Rajah’s cat appears to be exercising a deleterious influence on one branch at least of the fishing, viz., that for sharks. It appears that, in olden times, one fish daily was taken from each boat as a perquisite for the Rajah’s cat, or the poocha meen (cat fish) collection. The cats apparently have not augmented so much as the fishing boats, so this has been commuted into a [67]money payment of two pies a day on each successful boat. In addition to this, the Rajah annually levies a tax of Rs. 2–4–0 on every boat. Half of the sharks’ fins are also claimed by the Rajah’s poocha meen contractor.”

Writing concerning the Mogērs, Buchanan45 states that “these fishermen are called Mogayer, and are a caste of Tulava origin. They resemble the Mucuas (Mukkuvans) of Malayala, but the one caste will have no communion with the other. The Mogayer are boatmen, fishermen, porters, and palanquin-bearers, They pretend to be Sudras of a pure descent, and assume a superiority over the Halepecas (Halēpaiks), one of the most common castes of cultivators in Tulava; but they acknowledge themselves greatly inferior to the Bunts.” Some Mogērs have abandoned their hereditary profession of fishing, and taken to agriculture, oil-pressing, and playing on musical instruments. Some are still employed as palanquin-bearers. The oil-pressers call themselves Gānigas, the musicians Sappaligas, and the palanquin-bearers Bōvis. These are all occupational names. Some Bestha immigrants from Mysore have settled in the Pattūr tāluk, and are also known as Bōvis, The word Bōvi is a form of the Telugu Bōyi (bearer).

The Mogērs manufacture the caps made from the spathe of the areca palm, which are worn by Koragas and Holeyas.

The settlements of the Mogēr fishing community are called pattana, e.g., Odorottu pattana, Manampādē pattana. For this reason, Pattanadava is sometimes given as a synonym for the caste name. The Tamil fishermen of the City of Madras are, in like manner, [68]called Pattanavan, because they live in pattanams or maritime villages.

Like other Tulu castes, the Mogērs worship bhūthas (devils). The principal bhūtha of the fishing community is Bobbariya, in whose honour the kōla festival is held periodically. Every settlement, or group of settlements, has a Bobbariya bhūthasthana (devil shrine). The Matti Brāhmans, who, according to local tradition, are Mogērs raised to the rank of Brāhmans by one Vathirāja Swāmi, a Sanyāsi, also have a Bobbariya bhūthasthana in the village of Matti. The Mogērs who have ceased to be fishermen, and dwell in land, worship the bhūthas Panjurli and Baikadthi. There is a caste priest, called Mangala pūjāri, whose head-quarters are at Bannekuduru near Barkūr. Every family has to pay eight annas annually to the priest, to enable him to maintain the temple dedicated to Ammanoru or Mastiamma at Bannekuduru. According to some, Mastiamma is Māri, the goddess of small-pox, while others say that she is the same as Mohini, a female devil, who possesses men, and kills them.

For every settlement, there must be at least two Gurikāras (headmen), and, in some settlements, there are as many as four. All the Gurikāras wear, as an emblem of their office, a gold bracelet on the left wrist. Some wear, in addition, a bracelet presented by the members of the caste for some signal service. The office of headman is hereditary, and follows the aliya santāna law of succession (in the female line).

The ordinary Tulu barber (Kelasi) does not shave the Mogērs, who have their own caste barber, called Mēlantavam, who is entitled to receive a definite share of a catch of fish. The Konkani barbers (Mholla) do not object to shave Mogērs, and, in some places [69]where Mhollas are not available, the Billava barber is called in.

Like other Tulu castes, the Mogērs have exogamous septs, or balis, of which the following are examples:—

Āne, elephant.

Bali, a fish.

Dēva, god.

Dyava, tortoise.

Honne, Pterocarpus Marsupium.

Shetti, a fish.

Tolana, wolf.

The marriage ceremonial of the Mogērs conforms to the customary Tulu type. A betrothal ceremony is gone through, and the sirdochi, or bride-price, varying from six to eight rupees, paid. The marriage rites last over two days. On the first day, the bride is seated on a plank or cot, and five women throw rice over her head, and retire. The bridegroom and his party come to the home of the bride, and are accommodated at her house, or elsewhere. On the following day, the contracting couple are seated together, and the bride’s father, or the Gurikāra, pours the dhāre water over their united hands. It is customary to place a cocoanut on a heap of rice, with some betel leaves and areca nuts at the side thereof. The dhāre water (milk and water) is poured thrice over the cocoanut. Then all those assembled throw rice over the heads of the bride and bridegroom, and make presents of money. Divorce can be easily effected, after information of the intention has been given to the Gurikāra. In the Udipi tāluk, a man who wishes to divorce his wife goes to a certain tree with two or three men, and makes three cuts in the trunk with a bill-hook. This is called barahakodu, and is apparently observed by other castes. The Mogērs largely adopt girls in preference to boys, and they need not be of the same sept as the adopter.

On the seventh day after the birth of a child a Madivali (washerwoman) ties a waist-thread on it, and [70]gives it a name. This name is usually dropped after a time, and another name substituted for it.

The dead are either buried or cremated. If the corpse is burnt, the ashes are thrown into a tank (pond) or river on the third or fifth day. The final death ceremonies (bojja or sāvu) are performed on the seventh, ninth, eleventh, or thirteenth day, with details similar to those of the Billavas. Like other Tulu castes, some Mogērs perform a propitiatory ceremony on the fortieth day.

The ordinary caste title of the Mogērs is Marakālēru, and Gurikāra that of members of the families to which the headmen belong. In the Kundapūr tāluk, the title Naicker is preferred to Marakālēru.

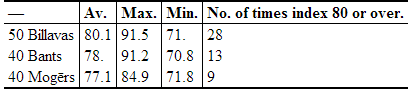

The cephalic index of the Mogērs is, as shown by the following table, slightly less than that of the Tulu Bants and Billavas:—