Mohenjodaro

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

From: Sharmila Ganesan Ram, April 6, 2021 The Times of India

Contents |

Mohenjodaro

The mound of the dead

Text and photographs by Ameer Hamza

If you’ve seen the back of a ten-rupee currency note carefully, you must have seen the photograph of a peculiar mound on it. It is called the ‘Mound of the Dead’ by archaeologists, and it is located at Mohenjodaro (literally, the mound of mohen).

Mohenjodaro was one of the principal cities of the Indus Valley civilisation. It flourished around 2,500BC and is one of the archaeological sites in Pakistan on Unesco’s list of protected monuments.

Sir John Marshall supervised its excavation in the early ’20s and his car is still in the Mohenjodaro museum, representing his presence, struggle and dedication to the place.

As a result of the excavation, almost one-third of the old city was recovered, revealing for the first time the remains of one of the most ancient civilisations in the Indus Valley. Typical of most large and planned cities, Mohenjodaro had streets and buildings.

The area roughly lodged 5,000 people, and had houses, a granary, baths, assembly halls and towers. The citadel included an elaborate tank or bath created with fine quality brickwork and drains; this was surrounded by a veranda. Also located here were a giant granary, a large residential structure and at least two aisled assembly halls.

From the excavations one can make out that the city was divided into two different sections; the lower and the upper parts. The upper area was man-made, and most probably it was from here that the rulers ruled. There was a great bath near this mound which everyone was allowed to use. The huge granary remnants are still beautiful even today.

The lower section was where the common man lived. The streets cut each other at exactly 90 degrees. They were nine metres long. Alongside the streets ran the drainage system, which was so advanced that no civilisation of its time could match it.

The houses were well-built and were mostly made in block style, with small windows for ventilation. Some of the houses were huge and some had a kind of plaster on them. However, most of that plaster has vanished now.

The most famous features of Mohenjodaro that have survived are the priest king wearing an ajrak, the square bull seals that have also been found in Mesopotamia (Iraq), the dancing girl and the weights they used. Its text has not been deciphered yet, which makes it impossible to ascertain their true social, political and religious life.

To add mystery to the Mohenjodaro drama, we don’t know what happened to the Indus Valley civilisation. It seems to have been abandoned about 1700BC. It is possible that a great flood destroyed it. The moving tectonic plates that created the Himalayas may have caused a devastating earthquake. It is also possible that its inhabitants may have been defeated by another civilisation.

Unfortunately, for all its charm and mysteries, this magnificent ‘city of the dead’ is in danger of getting soaked in salt — literally. Saltish water is rising rapidly, and if no action is taken immediately then we might lose this priceless heritage forever.

The Dancing Girl of Mohenjodaro

A

Arjun Sengupta , Divya A, May 26, 2023: The Indian Express

Discovering the Dancing Girl

The Indus Civilisation (3300-1300 BC with its mature stage dated to 2600-1900 BC), also known as the Harappa-Mohenjodaro Civilisation, had been long forgotten till its discovery was announced in 1924. While sites and artefacts from the civilisation were in discussion since the early 19th century, it was not until the 1920s that they were correctly dated and recognised as part of a full-fledged ancient civilisation, much like the ones in Mesopotamia and Egypt.

After the initial recognition as an ancient civilisation, a spate of excavations were conducted in the two major sites that were known till then – Harappa and Mohenjodaro. The Dancing Girl was discovered in one such excavation in 1926, by British archaeologist Ernest McKay in a ruined house in the ‘ninth lane’ of the ‘HR area’ of Mohenjodaro’s citadel.

Even though Mohenjodaro and Harappa became part of Pakistani territory after the Partition, the Dancing Girl remained in India as part of an agreement. Today, the bronze figurine sits in the National Museum of India as artefact no. HR- 5721/195, enthralling visitors in the museum’s famous Indus Civilisation gallery, often referred to as its “star object”.

Some descriptions

Over the years, the Dancing Girl has been an object of fascination for archaeologists and historians. Of particular interest has been the pose the woman strikes and what that means.

The figurine has “the pleasing stance of a young and spirited woman”, historian Romila Thapar wrote in The Penguin History of Early India: From Origins to AD 1300 (2002).

“This young woman has an air of lively pertness, quite unlike anything in the work of other ancient civilisations,” historian AL Basham wrote in his classic The Wonder that was India (1954). Mortimer Wheeler, director of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) between 1944 and 1948, described the figurine as his favourite. “A girl perfectly, for the moment, perfectly confident of herself and the world. There’s nothing like her, I think, in the world,” Wheeler wrote.

John Marshall, Director-General of the ASI from 1902 to 1928 who oversaw the initial excavations in Harappa and Mohenjodaro, described the figurine as “a young girl, her hand on her hip in a half-impudent posture, and legs slightly forward as she beats time to the music with her legs and feet”.

Inferences that can – and cannot – be made

As Marshall’s description suggests, it is the pose that the figurine strikes that has led historians to believe that the woman depicted was a dancer. However, there is no other evidence to support this claim.

Recent work on the issue has suggested that the “dancer” label came from readings of Indian history from later dates, when court and temple dancers were commonplace. American archaeologist Jonathan Kenoyer wrote in Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus (2003) that the dancer label was “based on a colonial British perception of Indian dancers, but it more likely represents a woman carrying an offering.”

In 2016, a paper by Thakur Prasad Verma in Itihaas, the Hindi journal of the Indian Council of Historical Research (ICHR), claimed that the figurine was in fact a depiction of Hindu Goddess Parvati. The paper attempted to tie the Indus Civilisation to Vedic Hinduism. This claim has been dismissed by most historians who say that there is simply no evidence to say with certainty who the Dancing Girl depicts or whether there was any worship of Hindu Gods in the Harappa-Mohenjodaro Civilisation.

What can be inferred from the bronze statuette, though, is the degree of sophistication of Harappan artistry and metallurgy. The Dancing Girl is evidence of the civilisation’s knowledge of metal blending and lost-wax casting – a complicated process by which a duplicate sculpture is cast from an original sculpture to create highly detailed metallic artefacts.

Moreover, the very existence of a figurine such as the Dancing Girl, indicates the presence of high art in Harappan society. While art has probably been around since the very beginning of human existence, the degree of its sophistication indicates a society’s advancement. The Dancing Girl by all appearances is not an object built for some utilitarian purpose – artists took great time to create an artefact of purely symbolic, aesthetic value.

B

Malini Nair, A sassy 5,000-year-old teen is back in the news, Oct 24 2016 : The Times of India

With a Pakistani lawyer demanding that India return the Dancing Girl of Mohenjodaro, the iconic figurine has become the subject of much dance and debate

She is a skinny , sassy, cool teen. And about 5,000 years old. So, what could the Dancing Girl of Mohenjodaro, all of 800gm and 10.5cm in height, have anything to do with the millennial world?

Lots, actually. The most charismatic face of the Indus Valley Civilization is not only being demanded back by Pakistan for the Lahore Museum, she has also become a subject of great interest among dancers and culture scholars.

“She's about fifteen years old I should think, not more, but she stands there with bangles all the way up her arm and nothing else on. A girl perfect ly, for the moment, perfectly confident of herself and the world. There's nothing like her, I think, in the world,“ colonial archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler had said of the inscrutable gawky girl cast in bronze.

But what happens to her when she g rows up? Last Saturday , at the Gati contemporary dance festival, Sujata Goel merged her own identity with the historical icon, reinterpreting her as a series of contemporary female figures. Here were the stylized poses and movements of women we have gazed at in contemporary images -the awkward ramp walk, a temple frieze, a Bharatanatyam posture, an item number, the provocative pinup, the bar dancer. Today , the dancing girl could have been frozen in any of these movements.

The Mohenjodaro figurine is riveting -upright, one arm behind her, hip out, leg slightly bent, eyes closed, full lips and hair in a loose bun.After she was found at the dig site in 1926, an inscrutable Mona Lisa-esque figure, she became the subject of much academic conjecture -was she Dravidian, Nubian or Baloch? Was she actually danc ing or simply in a univer sally feminine posture of impatience? She certainly looks impudent, agree his torians. Almost, says archaeologist John Marshall, as if she were impatiently beating time with her extended foot.

Goel says the pre cocious dancing girl's figure is in many ways ancient, classi cal and hyper-mod ern all at the same time -she is in control of herself and her sexuality .Could she possibly be sneering at the moralists around her, she asks? Goel's 40-minute dance collage was a deliberately stylized take on the 100 different ways the female form is presented on popular and elite platforms -hip out, bust out, expressionless but the eyes always inward looking.

The choreography has been evolving over a couple of years but Goel says her dance is very much a reflection of modern politics. “I was preoccupied with the concepts of beauty, seduction, eroticism and their power dynamics,“ she says.

The incongruous costumes and accessories include the full headgear of a classical dancer, and a busty skirt costume that is nearly traditional but stops at the knee. The idea, says Goel, is to be knowingly objectified. “That can be a liberating experience, I think,“ she says.

The demand that she be `returned' to her home in Pakistan has created fresh interest in this youngster. Apart from pa triotic indignation at the idea of her leaving the National Museum, social media was full of hilarious cracks about her: she looks like a woman in the ticket queue at the crowded Dadar station, a harried woman waiting for a bus, or a teenager in a sulk.

Historians have never really agreed on her “nautch“ status. Archaeologist Gregory Possehl puts it best: “We may not be certain that she was a dancer, but she was good at what she did and she knew it.“

At the discussions surrounding the dance at Gati, culture writer Sadanand Menon pointed to a historical detail on how political factors of the 1920s got her the name `dancing' girl. A debate was on then about the abolition of the Devadasi system.

“It was around this time they discovered this figure -a young woman, arms akimbo, in a tribhangi pose. And the figurine became conflated with the debate. It was also why classical dance revivalists took to saying our dance is 5,000 years old,“ says Menon who was told this by one of the archaeologists on the scene, H D Sankalia, in Pune, when the latter was in his 80s.

Unsolved mysteries

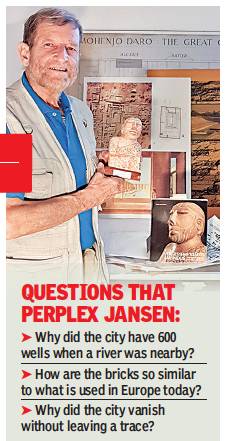

Dr Michael Jansen’s work

Sharmila Ganesan, April 3, 2021: The Times of India

From: Sharmila Ganesan, April 3, 2021: The Times of India

From: Sharmila Ganesan Ram, April 6, 2021 The Times of India

Sadly, Dr Michael Jansen has seen the Hindi film ‘Mohenjo Daro’. Unlike Indian viewers, the German has been unable to dismiss the Ashutosh Gowariker period drama — full of hilarious headdresses, happyeven-under-distress songs such as ‘Mohenjo Mohenjo’ (‘Mound Mound’) and other creative licenses — as just another unintentional Bollywood comedy.

“It’s an archaeological, scientific shame,” exclaims the 74-year-old Indus Valley researcher in an email interview. “Horses were not domesticated back then,” adds Jansen, whose love affair with the 4,500-year-old Mohenjo-daro in Pakistan’s Sindh began back in 1970 when a domesticated horse had first led him from Dokri railway station to this one-million-square-metre-wide prehistoric sprawl of brick walls and dry wells. “I know every brick by heart,” he says.

It’s not an exaggeration. If it has been nearly a 100 years since the first diggings in Mohenjo-daro in 1921-22 unveiled a new Bronze Age Civilisation, it has been over 50 years since Jansen got “married” to this sophisticated riddle of a city that left behind many questions when it vanished without a trace in 1900 BC.

He was 23 when he boarded a train from Peshawar to Sukkur, arrived at Dokri station at 3am, rested in the retiring room whose guestbook bore handwritten comments of famous previous travellers including British archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler, and travelled 10km on a tonga to Mohenjo-daro. “I’ve never forgotten the first view of the stupa in the morning light,” says Jansen, who spent ten winters in Sindh’s tents as director of German Research Project on Mohenjo-daro working with an international team of researchers.

Today, the chowkidars who played the double flute by the evening campfire and the Mohanas — the ‘river nomads’ on large houseboats shaped like the boat found on an terracotta amulet in Mohenjo-daro — are the stuff of nostalgia for Jansen. Even the young locals who helped him excavate the site have turned into middle-aged parents. Yet, Mohenjo-daro continues to colonise the septuagenarian’s imagination in the same obsessive way that Mesopotamia, archaeologist Max Mallowan’s muse, once colonised British author Agatha Christie’s. “The riddle is bound to outlive me,” he says about the city that hides more than it reveals.

In 1979, Unesco launched a ‘Save Mohenjo-daro’ campaign that collected around $20 million in donations. “The challenge was that saltpeter salts in the soil and other agents damaged the exposed brick structures. To avoid further destruction, further excavations were prohibited.” Later, in the 1980s, the German Research Project Mohenjo-daro — along with the Italian Mission of Professor Tosi — developed methods of ‘non-destructive archaeology’ with rich results. “Based on our research, new aspects came to light such as the underground extent of the site,” recalls Jansen, adding that Mohenjo-daro has been buried by more than seven meters of Indus silts over the last few centuries. Drillings proved that the city was more than double the size of what is visible today, “like the tip of an iceberg.”

Jansen’s favourite riddles are the city’s complex and unique water management and sewage system. While its many drains can be explained by its silty ground which would’ve turned muddy if water were allowed to collect, “it seems paradoxical that Mohenjo-daro once comprised more than 600 wells as a source for vertical water supply when the Indus river was nearby,” says Jansen, pointing out that, in Egypt and Mesopotamia, water was collected from the rivers at the time. Despite this sophistication, though, Europe, he tells us, had lost interest in the Indus Civilisation some years ago. This, because gold finds were rare and its endless burnt brick walls were deemed “too boring” for academic scrutiny. For Jansen, though, who recalls the coolness of walks through the shadowy “E-W streets” of the city, few things are more exciting than the trademark “one-hand” sunbaked bricks. “They have the same measures and proportions as the ones in use in Germany and Europe today: 7x13x25 cm with 1 cm joint. You can grip them with one hand,” says Jansen. In fact, “the mature Harappa, unfortunately, had been robbed of its burnt bricks to consolidate the Lahore-Multan railway track in 1854,” informs Jansen.

Compared to Egypt, Mohenjo-daro, Jansen says, shows all aspects of a ‘modern’ society with low-cost but high-tech infrastructure. “If 20,000 workers took 20 years to build a pyramid for just one person, the Pharaoh, in Mohenjo-daro, similar labour was invested in setting up sub-structures of the city, not for one ruler, but for the people themselves,” says the professor of urban history.

“The entire city seems to have disappeared without a trace. Why?” says Jansen, whose own research suggests problems with transport and inter-connectivity. “The Indus people seem to have been dealing with water transport both on rivers and on sea. An implosion of such a system might have led to a collapse of the communication system by land and water,” he says.

Given the absence of written sources, researchers must base their conclusions on material remains such as the seals whose script remains undeciphered. These days, he often fantasises about “finding a library with long texts telling us the history” or stumbling on something like Rosetta Stone which helped experts decode Egyptian hieroglyphics.

Meanwhile, Jansen will have to endure news about the damage that occurs at the site when school kids and oblivious locals walk on the ancient walls. Such incidents remind him of an essential gap he can only explain with a German word: ‘Verfremdungseffekt’. “It means mental distance between precious objects and regular ones.”