Moreh

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents[hide] |

The town

A brief profile, as in 2022

Bhabesh Sharma , August 28, 2022: The Times of India

From: Bhabesh Sharma , August 28, 2022: The Times of India

From: Bhabesh Sharma , August 28, 2022: The Times of India

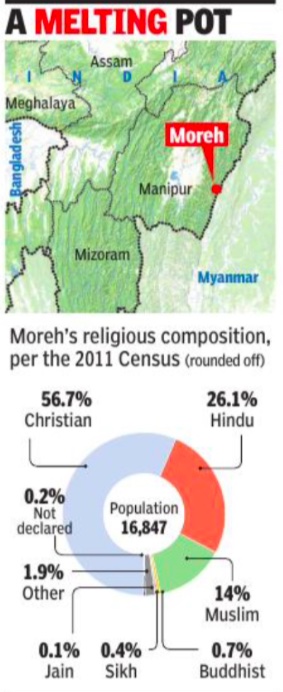

Moreh is a Manipur town on the India-Myanmar border. It is sometimes called the gateway to Southeast Asia, and you might think a town so remote would be home to only ethnic Manipuri people. But when two of its residents were brutally killed inside Myanmar territory on July 5, the streets of Moreh looked like a grieving miniIndia. The victims were Tamil men, and the mourners included Manipuris, Sikhs, Marwaris, Bengalis and Biharis, among others. This meltingpot profi le of the town might surprise a first-time visitor, but this is how things have been in Moreh for decades.

The town consists of nine wards, each with its own unique assortment of people. Although it has more Christians than people of all the other religions put together, temples of Hindus and Buddhists, mosques, and shrines to the sylvan deities of the Meitei people dot Moreh. At the town entrance, there is the “mandap” of theMeitei sylvan deity KonthokNganbi, besides severalchurches and a mosque. ANepalese temple and a Buddhist monastery stand closeby in a lane. On the main roadto the police station, the gurdwara is hard to miss. And at the southeastern tip is thetown’s biggest place of worship – a Tamil temple whosesouth gate leads into Myanmar’s Kabaw Valley.

Mixing For 50 Years

Moreh is home to roughly20,000 people of the KukiChin-Mizo group, 4,500 Manipuri Muslims, 4,000 Meiteis,3,000 Tamils, 2,000 Biharis, 500Nepalese, 150 Marwaris, 50-100 Bengalis, and some Sikhsand Assamese. Knowledge ofHindi is enough to fi nd yourway around, but all numbershave to be told in English. The infl ux of the non-ethnic people started in the 1970swhen they came here to tradein essential commodities andelectronic goods with Myanmar. From the start, Morehaccepted outsiders, eventhough the natives took careto preserve their unique ethnic cultures under the growing mainland infl uence. Leishangthem Brojen,general secretary of MeiteiCouncil, says Meiteis andTamils have formed a deepbond. Tamil community leaders bring tributes at Meiteicultural or traditional festivals like the ‘Lai Haraoba’of ‘Konthok Nganbi’, andthe Meiteis do the same onTamil festivals. The commonIndian prejudices of casteand religion are also missing here. Babu Pillai (47) is asmall trader who was born and grew up in Moreh. His sister’s son has married a Sikh woman. “My parents came here in the 1940s,” says Pillai. “I remember the days when all communities resided peacefully. Such harmony and inter-community coordination were great. ”

Tension Building Up

Why the wistful note? Pillai says the situation is changing. “At times, we feel insecure and suspect the violent era of the 90s is slowly rearing its ugly head because of the unrest in Myanmar. We are suspicious of the new faces coming from the other side of the border. ” He’s talking about Myanmar’s ‘8888 Uprising’ of August 8, 1988, which was followed by a crackdown that pushed Myanmarese refugees into the neighbouring Indian states, upset the demographic balance and created security concerns. There is a notable Myanmarese presence inside the town now. The Myanmarese traders’ infl uence is clear in Moreh market also, as all the weighing is done in their informal unit ‘choy’, not kilogram. One choy is equivalent to 1. 6kg.

Dependent On Myanmar

But it is not easy for the Indian authorities to stop the Myanmarese infl ux. The reason is simple – Moreh does not grow crops, nor does it rear livestock. All kitchen essentials, from chives to meat, come from across the border. “Vegetables, meat and spices are all supplied by Myanmarese nationals. However, we now use Indian spices which have better ingredients even though they are expensive,” says Ibomcha Khan, a Manipuri Muslim working at a popular eatery.

2022: drugs

Sourabh Sen, April 12, 2022: The Times of India

Moreh was once billed as India’s Asean gateway, a link to the economically booming group of 10 Southeast Asian countries. The Manipur town is an important transit point under India’s Look East policy that envisaged trade routes stretching out eastwards through Tamu on the other side of the Myanmar border. The central government has spent crores of rupees to build infrastructure in the town.

Despite the promise, today the small border town has become one of the biggest drug transit points in India.

Consider the value of brown sugar, a heroin derivative also called smack, confiscated in three raids in Moreh just on April 5. 1pm: 52 soap cases worth ₹4.2 crore 2:30pm: 55 soap cases worth ₹4.6 crore 4pm: 53 soap cases worth ₹4.4 crore This brings the total value of drugs seized in Moreh between March 25 and April 6 — a span of less than a fortnight — to ₹49.3 crore. Things weren’t always like this. But the winds of change have been blowing through the dusty little town for a while.

The changing face of Moreh

Back in 2001, driving down the 110-km road from Imphal — now a part of the Asian Highway 1 network running from Tokyo to Istanbul — was a terrible seven-hour experience. Your bones rattled and your anxiety levels went up as you drove through areas controlled by different militant outfits. As you rolled down eastwards from the misty hills of Tengnoupal, the ramshackle shanties of Moreh hit your eyes.

The roads stayed bad but the infrastructure slowly improved as the Look East policy — first championed by prime minister I K Gujral, then promoted by Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Manmohan Singh — started taking shape. In 2006, a guesthouse run by the Moreh Chamber of Commerce was one of the few places you could stay at night, unless the district administration or the Assam Rifles were hosting you. The caretaker would go home by 7pm, leaving a stern warning not to open the doors or venture out at night.

There would be groups of young men hanging out at street corners, drinking Chinese Dali beer and chasing No 4, a street name for heroin. Staccato sounds of gunfire would pierce the night’s stillness. Controlling Moreh was the key for both the administration and traders. Till the late 1990s, it was the Tamil Sangham — a group of Tamilians displaced from Yangon during the 1960s’ purges — which exerted control through moneylending. Then the Kukis, with kin across the border and all around, started getting elected or appointed to the local institutions.

Between 1991 and 2011, Moreh’s population grew from 9,600 to around 17,000. It inevitably led to tensions between the Kuki settlers from Myanmar, Muslim settlers from Bangladesh and the local Meiteis. In this potent mix rose the redoubtable politician Lukhosei Zhou. In a way, the saga of Zhou tells the story of Moreh’s drug trade.

The rise of Lukhosei Zhou, the kingpin

A Kuki of Myanmarese origin, Zhou started taking an active interest in Moreh politics in the late 1990s. In 2001, he became chairman of the district’s autonomous council, thus consolidating his control over the town. From then till now, he has been close to the political party in power in the state — first the Congress and then the BJP. It has given Zhou enormous power in the border town.

But Zhou’s proximity to the ruling party could not get him protection from the charges of drug trafficking. In June 2018, a team led by Thounaojam Brinda, an additional superintendent of the state police’s Narcotics and Affairs of Borders (NAB) department, arrested him from his house.

They seized heroin powder and amphetamine tablets called the World Is Yours worth ₹27 crore along with almost ₹60 lakh in cash. Chief Minister Biren Singh gave Brinda a gallantry award for the operation.

But in December 2018, a special court in Imphal gave Zhou an interim bail on health grounds, four days after the charges were filed. On January 5, 2019, Zhou’s lawyers told the court that he could not appear because a Myanmarese faction of the Kuki National Army had abducted him. However, in February 2019, Zhou reappeared and surrendered before the court.

In 2020, the same court acquitted Zhou, and the Manipur government decided not to appeal against it despite a sustained campaign by the state’s civil society groups. In protest, Brinda returned her gallantry award.

In an affidavit before the state high court in July 2020, Brinda detailed how she was pressured by politicians to let Zhou go: “After the drugs were found at his quarter, he asked me to allow him to call the director general of police Manipur and the chief minister that I did not permit. The following morning M Asnikumar (Moirangthem Asnikumar Singh, a senior state politician) came to my residence… He told me that the arrested [person] was the CM’s wife Olice’s right-hand man in Chandel (the district of Moreh) and that Olice was furious about the arrest. He told me that CM had ordered that [Zhou] be exchanged for his wife or son and to release him... I told him I cannot release him and thereafter he left.”

Brinda, now 43, was slapped with a contempt case in 2020 for “offensive” remarks on Facebook criticising the judiciary and resigned from the police in 2021. Zhou, 56, is now a free man.

Ties with Myanmar

As in 2021

Amava Bhattacharya, February 7, 2021: The Times of India

From: Amava Bhattacharya, February 7, 2021: The Times of India

From: Amava Bhattacharya, February 7, 2021: The Times of India

Why this Manipur town is keeping one eye on Myanmar

Decades-old trade ties between Moreh and the markets of Myanmar come under threat as the double whammy of Covid and coup seals borders

For years, the border town of Moreh, 107km from Imphal, has been the gateway to Myanmar. Literally, because all Indians have to do is hop across the India-Myanmar Friendship Gate without a passport and visa to get access to the bazaars of Tamu and Namphalong, both buying and selling goods and tying the two countries with the umbilical cord of commerce.

But the past 11 months have shut off this key gateway to their livelihood. In March, following the outbreak of Covid, the border was sealed. And on February 1, the day the Union Budget was announced, the Myanmar military staged a coup, which put paid to any chance of it reopening soon.

But Moreh’s multi-cultural mix of Kukis, Meiteis, Tamils, Biharis, Marwaris and Nepalis are nothing if not pragmatic. Far away from the diplomatic enclaves of New Delhi and Yangon, the people of Moreh and its Myanmarese counterpart Tamu feel that such is their dependence on each other that no coup can impact their business for long. “We have been doing business with Myanmar for decades, including when the junta was in power from 1962 to 2011. This latest coup should not affect our ties. Our only concern is the prolonged closure of the border. The Myanmarese side first said it would reopen on December 31, then January 31. Now with the situation changing in Yangon, it looks like the border will be shut for a while,” says Thilla Khan, Moreh resident and office-bearer of the local Tamil Sangam (association).

Khan belongs to the 3,000-strong Tamil community, which has, for long, controlled border trade. The Tamils who have settled in Moreh are descendants of refugees — mostly businessmen, traders, small shopkeepers — who fled Burma between 1948 and the 1960s, though most came after the first coup in 1962. Unable to adjust to life in Tamil Nadu where they first landed, a group of Tamil Chettiars made their way to Moreh in a bid to retur n to Bur ma. Stopped by the Burmese army, they chose to put down roots in this border town.

In the process, they’ve left their stamp on it, with a Tamil style shrine and a smattering of idli dosa stalls. Besides Tamil, most members of the community speak a cocktail of languages like Kuki, Burmese, Meitei, Hindi, and English and rely on cross-border trade for a living. Such was the draw of the ‘Burma trade’ that Khan, who was born in Ramanathapuram district of Tamil Nadu where his family had landed after their expulsion from Burma, migrated to Moreh against his family’s wishes.

The goods traded across the border are numerous, ranging from banians, lungis and sarees to food items like powdered milk and medicines. These are sold both in Myanmar’s Namphalong market, at walking distance from Moreh market, and in Tamu, further inside. Since Chinese and Thai goods are very easy to find in Namphalong, traders often bring back household items like rice cookers and mosquito bats for sale in Moreh and from there to other parts of India.

While traders are confident it will be business as usual even after the coup, general secretary of the Moreh Border Trade Chamber of Commerce, the Myanmar-born Surinder Singh Patheja, admits to being a bit apprehensive. “During civilian rule in Myanmar, the scope of India-Myanmar trade relations had expanded. Sixty-two items can now be traded duty-free, while for the rest, customs duty is required. We are already hearing of pro-democracy protests even in Tamu,” says Patheja, who arrived in Delhi from Burma in 1962 and then settled in Moreh ten years later. The Punjabi community in the town has declined from 40 families earlier to 13, but many still have relatives in Myanmar. Some have managed to go across and visit after 2018 when travel to Myanmar proper was allowed from Moreh with visa and passport.

It is the Myanmar military’s perceived proximity to China that has most worried traders like Khan. “It is difficult to compete with Chinese goods like electronics, mobiles, clothes, electrical parts and so on. They have flooded Namphalong market and affected our business. We have heard that the military in Myanmar is close to China. While they don’t interfere with local trade, it is better for India if there are democratic governments across the border,” he says.

E Bijoykumar Singh, professor of economics at Manipur University, confirms that the inflow of Chinese goods to Myanmar has increased over the years. “Some Chinese traders are said to be learning Manipuri to access the markets,” he says. However, even with the borders shut, Moreh’s ‘informal economy’ kept it going. Like every border town, there is an illegal flow of narcotics and gold. “Gold and drugs kept moving as usual, and will continue to do so, regardless of who is in power. However, it is important that the border reopens soon,” says Singh.

With the Modi government changing the ‘Look East’ policy to a reinvigorated ‘Act East’ policy, the strategically located town was hoping that it would be catapulted to an important trading post. The key to this transformation was the planned Trans Asian Highway, points out Ch Ibohal Meitei, director of Manipur Institute of Management Studies. “The Asian Highway (AH-1), part of the India-Myanmar-Thailand trilateral highway, is expected to connect Moreh to Mae Sot in Thailand, via Mandalay and Yangon in Myanmar. India has abolished ‘border trade’ in Moreh, and made way for ‘normal trade’. Now, large-scale infrastructure — warehouses, good roads and fewer security checkposts — are needed for Moreh to make the leap from informal border trade to a more transparent system of exchange of goods,” he says.

But till that happens, the Asian Highway remains a signboard on a rough road. And Moreh — existing between trades formal and informal, India and Myanmar, democracy and military — waits for its border to reopen.