Mumbai/ Bombay: history

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

The islands of Mumbai

Vaishnavi Chandrashekhar, May 2, 2022: The Times of India

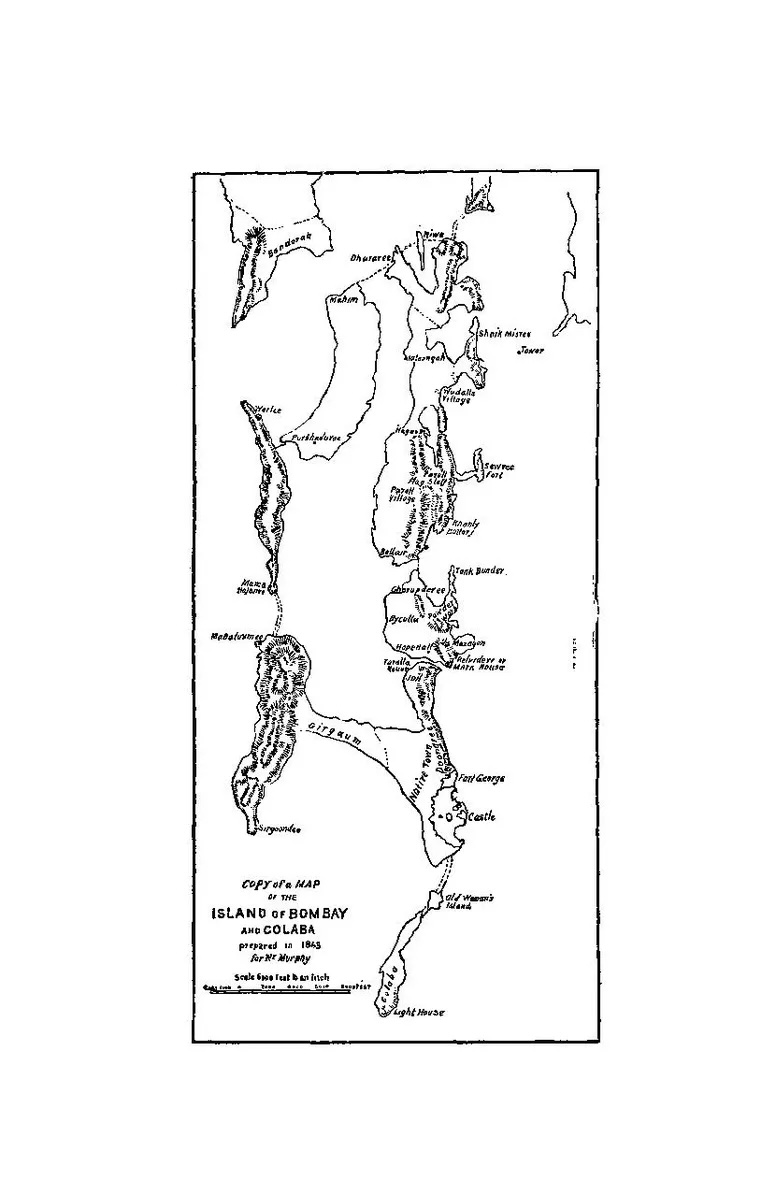

Everyone knows the story. Bombay was seven islands until the British joined them together through a series of reclamations and infills, paving the way for the rise of a brilliant port city. But a closer look at maps and records of the pre British era reveals a more complicated picture, say researchers, one that casts doubt on the city’s founding legend.

These documents suggest that the city was perhaps never seven islands, says Tim Riding, a historian working on early Bombay. That number, he says, comes from “a web of myth an d misconception” in the 19th and early 20th century.

So, how many islands was Bombay? The answer depends on whom you ask, and when.

Early Portuguese records are not definitive. A circa-1600 hand-drawn map depicts four islands—apparently Bombay, Mahim, Parel, Colaba—occupied by scattered landholdings (see pic). A 1635 sketch of the harbour shows only ‘Karanja’ and ‘Mombaim’ islands.

These early records were navigation sketches rather than precise maps, notes Mrinal Kapadia, founder of India Visual Art Archive. “The Portuguese were less concerned about defining land than about helping ships navigate the harbour,” he says, adding, “Early seafaring Europeans saw estuaries and channels, they had a sea-centric view. ”

Defining the islands was not important for the Portuguese also because they were a small part of the ‘Northern Province’ that extended beyond Salsette, notes Riding. It’s also likely why the Portuguese never considered reclamation—they didn’t need the land.

All that changed with the arrival of the English. Bombay was famously part of the dowry in the 1661 marriage of Portugal’s Catherine of Braganza and England’s Charles II. But whether that territory included only ‘Bombay island’ or other islands as well, especially the trading post of Mahim, was a matter of dispute for decades.

The English argued the space between the islands was not sea, as some previous views held, but tidal flats and mangroves submerged during high tide. An influential 1685 map by East India Company official John Thornton supports the claim, depicting Bombay as one big island including Mahim (see pic).

“There was a political imperative to have these all be one island,” says Riding, “because otherwise the English don’t have a coherent territory” in a region contested by Portuguese, Mughals, and Marathas. In the 1710s, the Company began building embankments to link Mahim to Worli, and by the next decade, the Portuguese had withdrawn their claim to Mahim.

So if the early British era claimed one island, where did the number seven come from? Possibly from a widely-reprinted 1843 map by newspaper editor Robert Murphy, who based his reconstruction on neighbourhood names.

By the early 1800s, the British had forgotten earlier disputes and begun rediscovering multiple islands, says Riding. Numbers such as four and six were mentioned, but the idea of seven islands gained ground. It was reinforced by ancient Greek geographer Ptolemy’s reference to a Heptanesia, or seven islands, on the west coast of India.

By the late 1800s, the transformation of seven malarial islands into one successful port had become the stuff of lore, a testament to British ingenuity. Marathi writer Govind Narayan marvels at the achievement in 1863. In 1902, SM Edwardes states with certainty that the Portuguese handed over seven islands to the British. Forgotten in this triumphant story are the contested earlier chapters. For Kapadia, the divergent visions of the islands shows us how landscapes can be fluid. “For me, Bombay is a place in time,” he says. Riding agrees. “What this tells us is that geography is open to interpretation,” he says, adding, “We may never know for sure how many islands [Bombay] was. ”

1668

The Portuguese rent Bombay to the East India Co for £10

Nergish Sunavala, When Bombay went to East India Co for £10 rent, March 27, 2018: The Times of India

No history tour of Mumbai ever concludes without the participants learning that the city was given to the British as part of Catherine of Braganza’s royal dowry when she married King Charles II of England. The Anglo-Portuguese marriage treaty was dated 23rd June, 1661, ratified on 28th August, 1661 and the marriage took place on 31st May, 1662. But none of these dates are quite as significant as 27th March, 1668.

It was on this day, 350 years ago, that King Charles II declared the East India Company (EIC) “the true andabsolute Lords and Proprietors of the [Bombay] Port and Island… at the yearly rental of £10, payable to the Crown,” writes Samuel T Sheppard in his book ‘Bombay’. King Charles was happy to hand over the territory which had been the cause of much trouble and expense because of constant friction with the Portuguese over port dues. In return for Bombay, he received a loan of £50,000 at 6% interest from the EIC.

Historians agree that it is this date, which marks the foundation of the city as the ‘Urbs Prima in Indis’, specifically because of the far-sightedness of the second governor appointed by the EIC, Gerald Aungier. “It was only when Gerald Aungier became

governor that the growth of Bombay really started,” explains Commander Mohan Narayan, Mumbai historian and the former curator of the Maritime History Society. “He set up the first Anglican Church in western India in two small rooms of the Bombay Castle, he set up the first court of law and he also started the first Anglican mint in Bombay Castle.”

After receiving Bombay in the dowry, the British Crown took time to claim it because the Portuguese Viceroy Mello de Castro quibbled about handing it over. “What tensions there must have been on the ground,” explains Bombay historian Farrokh Jijina, who conducts city tours. “The Portuguese dons being asked to hand over land they thought was leased to them, because a Roman Catholic princess so many kilometres away formed a marriage alliance with an English king.”

Then, there were disagreements over exactly how much territory had been ceded to the British in the dowry. In the original map, Salsette and Thana were shown as part of Bombay and Charles was hoping to get Bassein as well. However, he only got one island on which the fort was later built because the Portuguese refused to give up Mahim, Mazgaon, Parel, Worli, Sion, Dharavi and Wadala.

c.1803: Shushtari’s account

Arup K Chatterjee, Dec 4, 2025: The Indian Express

From: Arup K Chatterjee, Dec 4, 2025: The Indian Express

The forgotten fire that reshaped Bombay: Abdul Latif Shushtari’s chronicle of 1803

An obscure Persian chronicle reveals how a single fire redrew Bombay’s streets — and its future.

Just as Shushtari’s now better-known contemporary, Abu Talib Khan’s Masir-i-Talibi described Europe for Indian readers, Shushtari’s diary etched the social contours of India, especially Bombay, for Persian readers. It offered cultural, administrative, and economic commentary — a sort of proto-ethnography — through the lens of a non-European elite observer. According to the Iranian scholar, Jaleh Tajaldini, the author of a paper on Shushtari’s days in Bombay, his diary was much different from both colonial and Indian records of the time, and offers a unique perspective to complete historical views of the commercial capital of India.

Shushtari’s early life and times

Shushtari was a learned Iranian from Shushtar (in Khuzestan in modern-day Iran). He was born into a scholarly family and went on to train in literature, history, astronomy, and popular sciences of the time. Back in Iran, he worked as a trader in Bushehr. He left Basra in July 1788 and landed in Masulipatnam, in India, in August that year. Shushtari spent a good deal of his first decade in India as a diplomat, the Nizam’s ambassador to the British governor general in Calcutta, as a successor to his influential cousin, Mir Alam. Among other places, Shushtari also briefly stayed in Calcutta. In early 1801, he finished a travelogue, later published in Persian as Tuhfat ul Alam (Gift to Mir Alam). During Shushtari’s time in India, thirteen of his relatives were also in India, including Alam, with all of them being part of an elite Anglo-Indo-Persian commercial network. Unsurprisingly, Shushtari became a trustworthy political-commercial intermediary between Iranian and Arab merchants, on the one hand, and the ambassador of the Qajar dynasty (in Iran) and the British East India Company, on the other.

Bombay in the early 1800s was a busy, multi-ethnic harbour centred on the Fort, with gardens and farmhouses outside it. The town was already on a northward expansion. In the early nineteenth century, Parsis were economically dominant, being ship-owners, money-changers, cotton entrepreneurs, and traders. As such, they were closely tied to the East India Company’s commercial structures, alongside Persians and Arabs, who were also active in the cross-cultural mercantile circuit. Inter alia, Shushtari’s diary recorded Indian trade links, especially with China, its local industries (including cotton compression), coinage, financial challenges, the East India Company’s monopolies (including opium, salt, and tobacco) and the company’s introduction of paper money. More significantly, Shushtari was to become one of the rare chroniclers of the Great Fire of Bombay and of British urban planning after the fire, whereby he exhibited his close ideological affinities with the British Governor of Bombay, Jonathan Duncan.

Shushtari’s Bombay

Shushtari arrived in Bombay in December 1801 and remained there until November 1804. In 1801, an agreement between the Qajar government (which took control of Iran in 1796) and the British East India Company, Shushtari’s close aide, Haji Khalil Khan Ghazvini, was appointed as the Qajar court’s first ambassador in India. It was a period of regional instability for Bombay and its neighbourhood, marked by the continuance of Anglo-Maratha conflicts and irregular movements of goods from Pune. Meanwhile, Bombay continued to witness rapid commercial growth as an entrepôt for the Company. In some ways, Bombay, in 1803, was to India what London, in 1666, the year of the Great Fire, was to Britain — a multicultural trading port with numerous immigrant and floating populations. In the light of that analogy, Abdul Latif Shushtari would be to Bombay what Samuel Pepys was to London — in the respective years of the fires that struck the two cities — a diarist par excellence who relied on unofficial sources and eyewitness testimonies to bring alive the scenes of the fire while being in the thick of it.

Shushtari’s Waqaye-i Hind was the work of an informed resident with privileged access to Persian-speaking merchants and Company officials. His perspective blended eyewitness reportage with interviews (with Agha Muhammad, Mulla Firouz, Kavous) and official reports. Occasionally, he even relayed local rumours alongside official data. Therefore, his diary is best read as a critical contemporary source that must be compared with Marathi, Company and later accounts, even though it remains uniquely valuable for how it captured immediate human experience, social dislocation, commercial breakdown, and the politics of post-fire reconstruction.

A rare account of the fire

Shushtari recorded that the fire began on February 17, 1803, reportedly starting at 3 pm. Upon being informed by a messenger, through a letter, he first witnessed the conflagration, in the form of a terrifying scene constituted by smoke and successive explosions of gunpowder in the Company’s armoury, from a hill near his garden house outside the principal town, about 6 kilometres from the Fort.

According to Shushtari, the fire’s origin was in the kitchen of a fellow-Parsi merchant, Ardeshir Majusi, as told to him by the Iranian merchant, Agha Muhammad. Apparently, the Parsi reverence for fire rituals prevented Majusi and others from extinguishing it — at least, as far as Shushtari’s report suggests. This, apparently, aggravated the fire. However, here — as in a few other places — Shushtari’s account differs from other contemporary reports. Shushtari termed the fire a ‘terrible catastrophe’ that caused heavy destruction. It amounted to 12 million rupees of losses for the Company, besides damaging 1,400 houses, killing 22 Indians, 3 British, and 4 Parsis, and causing widespread homelessness.

On February 18, as commercial ships and caravans continued to arrive, Duncan ordered the construction of a temporary landing outside the white town. Relief and rescue operations, and inquiry commissions, were to continue until the first week of March. On May 1, 1803, another fire, though comparatively small, broke out on the island, prompting stricter inquiries and reconstruction plans.

The original fire consumed an enormous part of the island. Several properties were ruined, while merchant stocks and goods recently moved to Bombay from Pune and consignments bound for China also suffered tragically. Other secondary effects of the fire included soaring prices and scarcity of Bengali cloth, glass, rock candy, cereals, sugar, fragile Chinese goods, and coins — particularly the last. Gold and silver coins nearly disappeared from circulation, as the Company began issuing paper money immediately after the fire.

Other adversities that struck Bombay were large rent rises, rise of thefts during the city’s recovery, and mass departures (as many as 25,000 people leaving for Surat by one count) that were compounded by the Company’s strict reconstruction policy that mandated evictions near the Fort. Countless families were forced into tents and temporary shelters. Given the island’s dense extended-family households, a single burnt house often rendered many households destitute. And, for those who stayed back, looting and opportunistic appropriation of intact properties added to survivors’ losses.

The disaster became a catalyst for decisive Company interventions that came in the form of demolitions of ruined dwellings near the Fort, extending the buffer around the Fort (from c. 600 to 800 yards), and its insistence on one-storey, detached English-style houses with wide streets and cisterns. Initially, only military and Company officials were to be permitted to occupy the Fort area. These rules precipitated protracted disputes over land, eviction threats, and resistance by previous Fort inhabitants. As Governor Jonathan Duncan set up inquiry panels, villagers and officials debated the causes of the fire. Differing from Shushtari’s theory of Parsi religious scruples, Duncan’s circle suspected deliberate incendiarism by a motivated group of unidentified people.

The antecedents of modern Mumbai

The post-fire reconstruction programme, as documented by Shushtari, and also corroborated by East India Company records, ran on lines of regulatory, spatial and enforcement measures that were targeted at reducing future risks of conflagrations and securing the Fort as a strategic nucleus of the Company’s operations in Bombay. The reconstruction began with the clearance and demolition of burnt and adjoining structures near the Fort and mandatory rebuilding guidelines that favoured single-storey homesteads instead of densely packed, timber-and-mud constructions. The policy specified wider passages and streets to permit mounted and foot movement, eviction notices, and legal measures to deter looting and unauthorised rebuilding. Duncan’s regime framed these interventions in terms of public safety and military hygiene. The reconstruction combined hazard-mitigation aims with the reordering of Bombay’s urban social geography. What Shushtari did not necessarily record, however, was that these measures were met with contested land claims, displacement of poorer households, and long disputes over property rights and compensation.

Unlike British files, which prioritised formal appraisals of loss, supported by military and security concerns, and legal procedures, Shushtari’s diary highlighted commercial and social particulars. Compared with Marathi popular narratives that were characterised by moralistic explanations like divine vengeance, oral traditions, and in some cases — as in an account by Govind Narayan — suffered from dating errors, Shushtari supplied granular economic data and details of trans-regional linkages, especially with the Iranian Gulf. His positionality as an Iranian merchant and host to a Qajar envoy enabled even his digressions and inaccurate reports to be seen as empirical observations reflecting administrative practice and the fire’s social ramifications.

Shushtari’s representations of British actors, including Duncan, were marked by a pragmatic and frequently laudatory tone, which underplayed the local resistance to the reconstruction of Bombay, besides other expressions of popular resistance to the Company’s policies. For Shushtari, the British were largely instrumental agents of reconstruction and economic normalisation, steering India to its natural destiny by asserting the legitimacy of British rule.

Unreliable, yet indispensable

Despite the obvious possibility of Shushtari’s diary being met with an anachronistic anticolonial opposition, it remains of contemporary value today. As a non-British primary account, it expands archival pluralism by adding merchant-diplomatic perspectives to British colonial and regional Indian narratives. Besides, its micro-economic detail — on commodity flows, insurance claims, coinage and arbitrage, and market interruptions — offers empirical material for studies of early modern market resilience. Most importantly, perhaps, its details of built-environment failure furnish us with historical antecedents for debates on urban resilience and how authorities deploy emergency powers to restructure urban space.

Waqaye-i Hind, in this regard, is perhaps less of informative value and more of antiquarian value; though its records are ultimately less-than-reliable, its production was fostered by longue durée Indian Ocean trade circuits; its context is more important than its contents. Above all, the diary makes it transparent how the fire did not merely consume lives, homes, timber, and goods. In their place, the Company burned a new civic order into Bombay’s centre, as Shushtari celebrated every Anglicizing turn of the city.

References

Tajaldini, J. (2021). Bombay in the Early Nineteenth Century: From the (Almost) Lost Diaries of Abdul Latif Shushtari. South Asia Research, 41(1), 53-69.

East Indian villages

As of 2025

Sonal Gupta, Feb 26, 2025: The Indian Express

The Maximum City has many Bombays within it. One such is Khotachiwadi, a 19th-century heritage precinct in Girgaon, popular for its Portuguese-influenced architecture and its diversity, that shows both in its buildings and through its people.

It is hard to miss Lynette Fernandez, 82, who spends her evenings on the porch of her century-old bungalow, chatting with passers-by. “We all grew up together. We would have these ‘pound parties’; no alcohol, just soft drinks. And each of us would bring something,” says Fernandez, as she points to the Girgaum Catholic Club that abuts her house. “There were many Catholic and Hindu families. We would exchange sweets on Diwali and Christmas,” she adds.

But like many others in the area, she finds herself in an existential battle as everything around this urban village is changing rapidly.

Khotachiwadi, once part of a vast coconut plantation, stands out for its cobbled, narrow lanes, colourful single-storey bungalows, with sloping tiled roofs and wood-frame porches. The sounds of the city are left far behind, its streets dominated by pedestrians.

How the East Indian community evolved

Since the 19th-century, several communities, including the East Indians, Pathare Prabhus, and Panchkalshis have settled here. It was the association with the British East India Company (EIC) that lent the name to the indigenous community. “They never called themselves East Indians until around 140 years ago,” says Fleur D’Souza, former head of the History Department at St Xavier’s College.

Soon, in search of employment, other Christians from across the west coast began streaming in. The original inhabitants of Bombay banded together as the East Indians and demanded that the sons of the soil be differentiated from the others. “The East Indian community started off as a political community. The name ‘East Indian’ does not reflect geography but history, culture and community consciousness,” says D’Souza.

The East Indians trace their roots to different castes and occupational groups such as the Kunbis (agriculturists), Agris (working in salt pans), Kolis (fishermen), Bhandaris (toddy-tappers), Kumbhars (potters) and even the urban westernised elite, adds D’Souza.

Conservation architect Pankaj Joshi, principal director, Urban Center Mumbai, explains that those close to the city, with stable jobs in the colonial administration, excelled.

Many East Indians grew to become well-known families of Bombay. For instance, Joseph ‘Kaka’ Baptista was the president of the Indian Home Rule League. He became the mayor of Bombay in 1925. Meanwhile, the younger generation began migrating. “In the last 40-50 years, almost every family has someone abroad and that leaves only senior residents in the locality,” says Joshi.

In the real estate grip

Now with the shift in the city’s centre from the south to the west and east of Mumbai, areas like Khotachiwadi are soft targets for redevelopment.

Land revenue documents classify some of these urban villages as gaothans, which were taxed differently from the newer settlements. The term ‘gaothan’ was used to refer to the core of the village with settlements usually built on a higher ground.

Scattered across Mumbai, the gaothans have become footnotes to the city’s Portuguese past. The East Indians are fighting hard to preserve their heritage under the shadow of gentrification and commercialisation. But not all development is bad – some welcome it, while others find it corrosive to the community.

At Matharpacady, some bungalows have already been converted into apartments. “We have tried our best to maintain the originality of our village,” says Julius Valladares, 65, a third-generation resident, “Our greatest fear is that politicians and builders will exploit the village commercially. There is talk about redevelopment, but we hope that the project will be shelved.”

In Bandra, gaothans like Ranwar and Pali have turned into commercial hubs. Pali bungalows hold a rustic charm of a gaothan yet one cannot but notice the names of salons, design firms, cafes and restaurants on plaques. This gentrification has also meant an increased anthropological interest in the community.

Nikhil Mahashur, an architect and restorer, who organises heritage walks, says, “The locals who want good rent allow these restaurants to crop up. It allows more people to know about the village. Awareness is important.”

While gentrification, as one has seen in New Delhi’s Haus Khas Village and Shahpur Jat, may not be the answer, it is not uncommon for residents in these areas to feel the weekend hustle on the streets. For others, it’s about being in a neighbourhood where they no longer know the people next door.

André Baptista, archaeologist and historian, warns against the “gimmickisation of heritage.” For instance, the residents of Khotachiwadi, which has largely retained its heritage structures, have had tourists invade their private spaces. “The residents started feeling like they were in a zoo,” says Baptista.

In Vile Parle’s St Francis Pakhady, only traces of the original 200-year-old gaothan remain. Alphi D’Souza, the global head of the Mobai Gaothan Panchayat and a resident of Vakola village, says that there were once 189 gaothans in Mumbai. The figure is now roughly less than 100 as many have been absorbed into the city after redevelopment.

He adds that the phenomenon is “natural” because “families are growing and there’s no place”. “All bungalows are giving way to big buildings. But these houses cannot go over one floor. The Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) has a restriction on height,” he says.

Community at the centre

Gaothans have been stuck in legislative limbo for years now. The status of their heritage tag is debatable amid the many draft lists published by the state government over the years. The rules governing their development have also been contested.

Joshi flags a new rule in October last year that says gaothans can be considered under the provision of cluster redevelopment. “That is a major threat. We are saying let the community decide. We never asked for cluster development. We are not slums. We are the original indigenous communities of Maharashtra.”

This trapeze act of “preserving and un-preserving” is an urban conundrum across cities. In the preservation of gaothans, Baptista asks: “Are we just preserving the architecture and therefore just the shell of what exists? That is not really cultural preservation because without its vibrancy, the essence is lost.”

Joshi concurs that the choice should be with the residents. “You cannot club all of them under one provision. Some gaothans, where there is no pressure of development and they want to retain the heritage fabric, they should get to do that. Some gaothans can incrementally grow if they need. And those who desperately want redevelopment, should have that choice.”

Renaming streets, institutions

1940- 2021

From: January 11 The Times of India

The row over Aurangabad’s rebirth as Sambhajinagar has turned the spotlight back on Mumbai’s tryst with renaming its roads and institutions. A look at city landmarks that escaped nominal reinvention

BOMBAY HIGH COURT

In 1961, a move to rename Bombay high court as Maharashtra high court was struck down by BP Sinha, then chief justice of India, saying the Bombay high court had set “high standards and traditions” and that all that would be lost if it were renamed.

MALABAR HILL

In the 1990s, if a Shiv Sena corporator had had his way, Mumbai’s swishest area would have been called Ram Nagari after Lord Ram who, according to legend, had stopped here on the way to Lanka.

KHOTACHIWADI

Residents of this heritage East Indian Christian enclave of quasi-rural houses in Girgaum protested when they came to know that it was to be renamed Patrakar Appaji Pendse Marg in 1982. BMC still went ahead with the renaming but residents removed the new name boards when the cop guarding them went off for a cup of tea.

KHAR

In 1963, the Swami Vivekananda Birth Centenary Celebrations Committee, had requested the BMC to change the name of Khar to Viveknagar.

CHEMBUR

Politician Murli Deora had once urged that Chembur be renamed after Raj Kapoor, who used to reside in the suburb for many years.

NAGAR CHOWK, CST

A proposal to rename CST’s Nagar Chowk as Lata Mangeshkar Chowk was rejected by the BMC in 2000. The administration reasoned that roads cannot be named after living personalities.

CARTER ROAD, BANDRA

A move to rename Carter Road after Smita Patil was opposed by some residents who felt it would inconvenience them

RAILWAY STATIONS

The state had considered renaming Marine Lines as Sonapur, Charni Road as Girgaon and Grant Road as Gavdevi. In 1997, a proposal had sought to rename Churchgate station as Deshmukh station after the economist and first RBI Governor of India, CD Deshmukh.

MAHATMA GANDHI ROAD, BORIVLI

To protest the increasing number of beer bars in Borivli in 1997, citizens asked the municipal commissioner to rename the Mahatma Gandhi road ‘Beer Bar road’ Text: Sharmila Ganesan Ram