Mumbai: Kamathipura

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Kamathipura

2016: Real estate drives flesh trade out

The Times of India, May 27 2016

Lure of real estate driving lust out of Mumbai's oldest red light area

Vijay Singh

A frail, old woman limps out of the 14th lane of Kamathipura to the pavement where the huge City Centre mall stands and stretches out her palm hoping for some alms. She was once a sex worker in the city's oldest red light area, and has now fallen on hard times with age.

Business is not very good nowadays. Everything is changing in Kamathipura; most of the `hi-fi' sex workers have moved out to the suburbs, or do business on Twitter and WhatsApp. Service class (white-collared) people are moving.

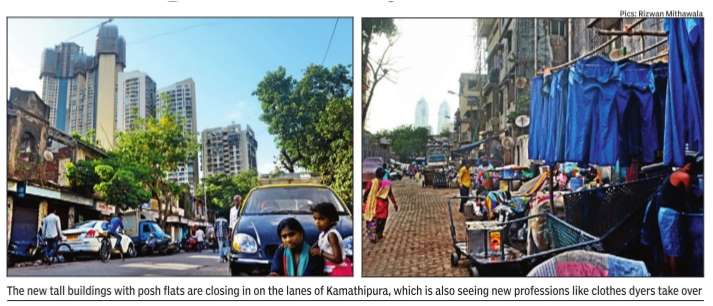

Lust has suffered a body blow at Kamathipura as real estate and new businesses become the top driving forces, slowly chiselling out a new face for this clichéd `pleasure zone' close to both Mumbai Central and Grant Road stations.

“As more and more middle class and upper middle class people have started moving to Kamathipura, strong intolerance has started showing towards the poor, especially the sex workers, said Brijesh Arya of Pehchan, an NGO working for the rights of homeless workers at Kamathipura for close to a decade.

Kamathipura is now home to many embroidery workers, clothes dyers, and even lawyers, chartered accountants, and regular office crowd, he added.

In the 13th lane, S K Jain, a chartered accountant by profession, said he started living there with his family two years ago. “Geographically , this is a good place, located close to Mumbai Central station.The stigma attached to the name Kamathipura is also going as a decent crowd has come here. Change is inevitable,“ said Jain.

The social activists and cityscape enthusiasts of Pehchan and RaahGeer group have now decided to organise a Kamathipura Night Walk on May 27 and 28 in a bid to capture the urban history and re call some tales associated with the area before it transforms into another concrete jungle.

“At Kamathipura, the basic fabric of people and local trades is fast changing. This is the time to see Kamathipura by night before it all chang es, said architect Deepa Nandi of RaahGeer.

Milind Deora, former South Mumbai MP, said people have approached him to change the area's name as it is linked to the sex trade.“Historically, it was so called because migrant workers from south India called `kamathis' had settled here.Now, residents want a different name altogether. Real estate is making inroads into all such old areas, including Kamathipura,“ said Deora.He backed cluster redevelopment of the entire neighbour hood for the sake of better modern systems.

About the fate of the poor, homeless and the sex workers, BJP's Shaina NC said, “There are various NGOs working in these areas to rehabilitate those pushed into sex trade. Human trafficking is illegal, so their lives must also be transformed for the better. “The first AIDS-related case was detected in Mumbai in 1986. By 1999, the disease had spread rapidly in Kamathipura, leading to aggressive mass awareness by activists and celebs. Now, over 80% of sex workers are out of these areas, mainly due to economic hurdles. The red light area is on its last legs,“ said Dr Ishwar Gilada, veteran campaigner against HIVAIDS.

Kamathipura children’s success stories

2021

Sharmila Ganesan, July 18, 2021: The Times of India

From: Sharmila Ganesan, July 18, 2021: The Times of India

Recently, when a viral Twitter thread by an Indian media portal celebrated her rise from Kamathipura to New York’s Bard college with shiny hashtags like #Inspiration and #Chaseyourdreams, Shweta Katti laughed to herself. “I dropped out after a year and I don’t regret it. That’s where my journey of self-discovery began,” says the 26-year-old from Italy’s remote Pomaia village where she is now studying Buddhism. Katti knows the complex story of how she got here does not fit society’s tidy, linear narrative of success but says she’d rather bask in her personal triumph over her inner struggles than be reduced to “Monday motivation”. “There’s more to me than just the first girl from a red light district who went abroad,” says Katti, in whose wake three more girls from Kamathipura are studying overseas.

Often dismissed in positive hashtags and clickbait headlines, the undulating trajectories of children from marginalised backgrounds who win crowdfunded opportunities to study overseas, remain unexplored. Beyond the fairytale send-offs, lie challenges stemming as much from India’s rote educational system as its social inequities.

“Superficial confidence” is what Katti now calls the attitude with which her18-yearold self had walked into class on her first day at Bard College in 2013. For Katti, who had studied in a Marathi medium school, the transition to the “elite college” was intimidating. Besides the feeling of “not being good enough”, the fear that “my achievement came from a story and not from merit” and the initially inscrutable accents of American professors, the palpable economic gap and intense academic standards triggered in her anxiety and depression — the same emotions that had kept her from attending a single lecture throughout first year in a Mumbai college.

“It takes work for daughters of sex workers to own their narrative,” says Trina Talukdar of the NGO Kranti, which had helped Katti — who had grown up above a brothel, suffered sexual abuse and endured colourist nicknames throughout school — tide over her selfworth issues and helped many children of sex workers pursue higher education. “Their survivors’ mindset makes no room for aspiration,” says Talukdar, adding that unlike local colleges which insist on marks for admissions, foreign universities pay heed to their background-honed grit, resilience and other skills.

What helped Farah Shaikh, the second of four daughters of a bar dancer who had taken up sex work to survive after her husband’s demise, recently graduate from Los Angeles’ University of The West, was “hard work”. Like Shaikh, an aspiring child counsellor, Katti too would’ve chosen psychology had she continued at Bard college but is grateful for the three semesters she spent there. “I became a global citizen then,” says Katti, who lived with foreign roommates and became more “politically and culturally aware”. Soon after, she had applied for a multicountry study-abroad programme on a ship where subjects included sociology and fiction writing. Here, Katti would relate to the “vulnerabilities” of the underprivileged in South Africa and find parallels to India in Vietnam.

Later, through her internship at Kranti in Mumbai, plays at Edinburgh Fringe Festival, a course in social entrepreneurship in the US and a debilitating Tuberculosis, old feelings of fragility would surface intermittently till she found respite in spirituality. Now, the 26-year-old UN Youth Courage Award winner is happy to hashtag her journey: #Selflove.

Nagpada

Sarvi restaurant

Heena Khandelwal, Aug 10, 2024: The Indian Express

They say if you are looking for the best seekh kebab in the city, Sarvi is the place to go. For generations, loyal patrons—like Boman Irani who went on record to share how his father used to enjoy their seekh kebab and now he, his son and grandson devour them as well — attest to its consistently excellent taste. But what’s the secret behind delivering top-notch kebabs for over 100 years?

“It is the barkat of this place. Many have learnt here and moved on to other restaurants but none could replicate the taste,” said Mohammad Reza Paknejad, an 80-year-old Irani gentleman and a mechanical engineer from Matunga-based VJTI Mumbai. He has been managing the establishment for the past 50 years. “We are also good paymasters — the meat arrives in the morning, and we settle the account in the evening,” he noted, adding that they also buy buffalo meat — a key ingredient at the establishment — in bulk. “Since we buy kilos and kilos of it, we are able to segregate different parts for different preparations, reserving the best for seekh kebabs.”

Parked at a corner premise opposite Nagpada Police Station, Sarvi is spread across 2,000 sq ft and has no signboard. But because this unassuming place has been parked at the same spot for over 100 years and has a loyal base of customers, such fineries have no bearing on its sales, which start as early as 5.30 am. “As Boman (Irani) mentioned in his interview, ‘Sarvi is so famous that it doesn’t need a board,” he laughed.

Going back in time

Sarvi was established in 1920 by Haji Ghulam Alli Sarvi, a gentleman of Irani descent. “It was his uncle who came to India and called him here. Sarvi understood food. Within a couple of years, he invited a specialist from Iran to make seekh kebabs here and what he did has been maintained since,” shared Paknejad, adding that Sarvi was a title he was bestowed with courtesy of his house being located on the first lane of his village near Yazd.

Legend has it that writer and playwright Saadat Hasan Manto was a regular at Sarvi. While Paknejad, also an Iranian who was asked by Sarvi’s son to manage the restaurant in 1974, can’t confirm or deny this piece of information, he shares that he has seen a lot of celebrities dining at Sarvi during his time at the restaurant, including actors Mahmood and Madhubala. “I have also heard about Raj Kapoor.”

In matters of taste

Sarvi’s menu features various dishes, with seekh kebabs, tandoori roti, paya soup, and masoor pulav being the most popular. The seekh kebab, once priced at Rs 2, is now Rs 50 in the air-conditioned mezzanine and Rs 40 on the ground floor.

We sampled Sarvi’s specialty, the buff seekh kebabs, which delivered on flavour as always. The kebabs, served with a runny mint chutney, were tender and flavourful with a melt-in-the-mouth texture. Unlike many places, they aren’t overly spicy or heavy; the balance of masala is subtle and just right. Each serving comes with a plate of mint leaves and lemon slices. “Kebab is very hot in nature. The mint leaves help cool it down and aid digestion, which is why we recommend chewing on them,” shared Paknejad.

He also noted that their keema and kebabs are so good that even local butchers come to their restaurant. Each dish at Sarvi, we learnt from him, is prepared twice daily to ensure optimal flavours. Additionally, they grind their spices in-house and avoid red chilli powder, using green chilli to achieve the right level of spiciness.

While the paya soup was dominated by turmeric, the masoor pulav was a highlight. This dish, popular in some Muslim communities but rare in restaurants, featured rice, whole masoor dal, and mutton keema. It offered a delicate meaty flavour with a dash of tanginess and a satisfying texture from the masoor dal.

Going forward

Paknejad’s son, Ali, has various expansion ideas, but the old man is hesitant. “We need a consistent supply of high-quality buffalo meat, and transporting it across the city has become increasingly difficult. It’s only feasible in areas like Kurla or Jogeshwari,” he explained. For now, Paknejad continues to come to the restaurant daily, arriving by noon, taking his round, heading to his nearby office and returning at 3 pm for lunch, which includes paya soup and tarkari (sabzi) that he brings from home. “I believe it’s important to be home for dinner with my family. I’ve told Ali to maintain the current setup while I’m alive, and then he can expand as he wishes,” he added.