Mumbai: Raj Bhavan

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

A history of the building

Bunker was built as a hiding place during unrest

From: Shenoy Karun, ‘Raj Bhavan bunker was built by Brit guv as a hiding place during unrest’, October 28, 2018: The Times of India

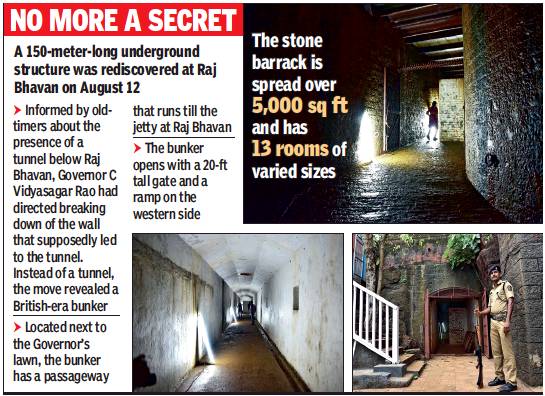

The 13-room bunker that was discovered under Raj Bhavan in Mumbai two years ago perhaps was not an armoury after all. Also, perhaps it cannot claim the kind of antiquity some historians have attributed to it. According to a 1983 book by British historian Jan Morris, the governor of the then Bombay was forced to build it in the last decades of British Raj, fearing patriotic unrest.

“Empire was not all hospitably idyll, though, and in later years the life of a governor of Bombay was frequently at risk. In the last decades of British rule in India, when this city seethed with patriotic unrest, they built an underground bunker beneath the happy bungalows of Malabar, equipped with bedrooms and kitchens for a long stay: a motor-road led into it, big enough to accommodate the governor’s Daimler, and a water-gate in the rock-face gave access to a jetty, in case His Excellency needed to make a hasty getaway when the ball was over,” wrote Morris in her book Stones of Empire: Buildings of the Raj.

Long forgotten, the bunker was rediscovered in August 2016, when PWD officials decided to pull down a wall that blocked its entrance. A 150-metre passage gave access to a 5,000-sqft area with 13 rooms, that marked as shell store, gun shell, cartridge store, shell lift and workshop.

According to Morris, among all the government houses of British India, the governor of Bombay’s seaside residence at Malabar Point was the most desirable to modern tastes. “This was hardly a palace in any conventional sense, but rather a cluster of white bungalows, mostly in traditional Anglo-Indian style, grouped on a rocky promontory above the sea, and surrounded by lawns, gardens and wooded walks along the seashore, where cuckoos sang, pet dogs were tearfully buried, and Hindu fishermen habitually came ashore to worship at a waterside temple,” she wrote.

Morris wrote that the most interesting building in the group was the big ballroom which formed the heart of it: “This was a large wooden structure, less like British India than imperial Malaya or Borneo—rather a Conradian thing, except that its paintwork was always impeccable, and its denizens allegedly respectable.”

A former journalist with The Times, London, Morris had served as a spy in Palestine and Italy during the Second World War and had climbed Mount Everest midway in May 1953, only to hastily return to file the story that Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay had reached the summit.