Munur: Deccan

Contents[hide] |

Munur

This article is an extract from THE CASTES AND TRIBES OF H. E. H. THE NIZAM'S DOMINIONS BY SYED SIRAJ UL HASSAN Of Merton College, Oxford, Trinity College, Dublin, and Middle Temple, London. One of the Judges of H. E. H. the Nizam's High Court of Judicature : Lately Director of Public Instruction. BOMBAY THE TlMES PRESS 1920 Indpaedia is an archive. It neither agrees nor disagrees |

Munnur, Munnurwad, Munnud Kapu — a widely diffused Culti- vating caste, probably an offshoot from the Kapur and indigenous to H.E.H. the Nizam's Dominions. The Munnur caste may b« regarded almost as a nursery from which many mixed classes scattered all over the Dominions, as, Telagas and other mendicant and menial castes, are propogated.

Origin

The name Mun-nur, which is Telugu for three hundred, has been made the subject of several legends which, more or less, explain the origin of the caste. One of the legends traces their descent from the Raja Bhartrahari and his three hundred wives of different castes. The Raja, says another, was so disgusted with his faithless wives, that he left his kingdom and retired into seclusion and the sons, born of the licentious women after the retirement of their husband, were called Munnur. A third story represents the Munnurs to be the descendants of a Kapu woman, who was confined in a dungeon, with three hundred male prisoners, where she conceived ' and was delivered of a son. The mother could not, however, point out the father of the boy and as she was associated with three hundred males, the boy was named Murmur, meaning born of three hundred. These legends tend to support the mixed origin of the caste, a view which respectable members of the community appear to be very reluc- tant to entertain.

Internal Structure

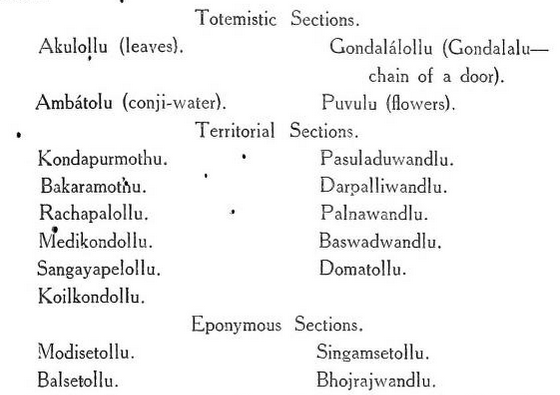

The internal structure of the Munnur caste is simple, the entire community being formed into one endo- gamous group. They have only one gotra 'Pasnur' which is obvi- ously inoperative for the purpose of controlling marriages. The mar- riages are governed by exogamous sections based upon family names of 'Vanshams.' A few of the sections are totemistic, the others are of a territorial or eponymous character, the eponym being the name of the founder of the section. Some of their sections are given below : — ,

The Murmurs are said to form a hypergamous group with the Tota Baljas, to whom they give their daughters in marriage, but they them- selves do not enjoy the same privilege in return. The Munnurs observe the simple rule that a man may not marry a woman of his own section and supplement this by a simple table of prohibited degrees. Thus a man is allowed to marry a woman of any other section, provided that he abstains from marrying his maternal aunt and any of his first cousins except the daughter of his own mother's brother. A man may marry two sisters, provided the elder is married first. So also he is allowed to marr>- the daughter of his elder sister. The Munnurs do not, in general, marry their daughters in families from which they have already taken girls in marriage.

Marriage

The Munnur girls are married as infants between the ages of five and ten. Should a girl attain puberty before marriage, her parents are disgraced and have to undergo 'Prayas-chitta' (expia- tion). Connubial relations may commence even before the girl attains sexual maturity, but not until a special ceremony has been per- formed, when guests are feasted and the pair are presented with clothes Rnd jewels. Polygamy is allowed, but is seldom resorted to unless the first wife is barren or incurably diseased.

The marriage ceremony resembles that of the Kapu caste. The first proposal of marriage is made by the boy's father who, on the choice of a suitable girl for his son, pays a formal visit to her house and presents her with clothes and half of the jewels she is to receive a wedding gift from her husband-elect. A council of the caste Panchayat being called, a Brahman examines the horoscopes of the parties and if they are found to agree, he finds an auspicious day for the wedding. Sixteen rupees are paid to the father of the bride as her price, whereupon the Brahman is dismissed wifh Dakshna (his fees). Wine is circulated among the guests in token of the confirma- tion of the match and after distribution of Pan-supari and perfumes the assembly disperse to meet again at night for dinner. The bride's people also visit and inspect the bridegroom. Invitation letters, sprinkled over with saffron water, are sent to relatives and friends calling upon them to attend the ceremony. A fortnight before the wedding, Pinnamma, the goddess of fortune, is worshipped by both parties separately in their houses. Vyankatswami and Raja Bhartri- hari are also honoured, the latter being representcid by five unmarried boys, to i.vhom dresses are presented and a feast given." A marriage panaal, supported on twelve posts, is erected in front of the boy's house and is tastefully decorated with young plantain trees, mango and cocoanut leaves and flowers. The Devada (wedding) post, which consists of a branch of a Salai tree, is cut and brought by the mat- ernal uncle or brother-in-law (sister's husband) of the bridegroom. It is ceromonially set up in a pit in the centre of the wedding booth and is surmour/ted with a lighted lamp which bums throughout the ceremony. On the day previous to the wedding, five married women, whose husbands are alive, proceed with five pots to a well or a river, and haviig offered puja to Ganga, or the water goddess, fill the pots with water and return to the wedding canopy. One of the pots, with its mouth covered with mango leaves, is placed in the gods' room and the water from the other pots is sprinkled all over the ground which has been previously plastered with cow-dung. The ceremo- nies that follow correspond, in all respects, to those observed at a Kapu marriage and have been fully described in the article on that caste. The essential, or the chief feature, of the ceremony is believed to be Kanyadan, or the formal gift of the bride by her father to the bridegroom and the bridegroom's formal acceptance of her. It is performed thus. The parents of the bride wash the feet of the bride- groom and^ place m his hands areca nuts, pieces of cocoanut kernel and some coin. The bride places her hands over those of the bridegroom and her father holds them in the cavity of his hands while her mother ppurs water over them. The priest then makes the father of the bride repeat three times that 'the girl is given as a gift to the bride- groom who fo?mally and ceremonially accepts her by thrice reciting Mantras to that effect. The tying of the pusti, or lucky string of black Deads, round the bride's neck, ' Jilkarbium,' or exchange of cumin seed and jaggery, and ' Padghattanam,' treading of each others feet by the bridal pair, are also deemed as important parts of the ceremony. It is said lihat the pair are wedded standing in bamboo baskets with a leather strap placed in each.

Puberty

A Munnur girl, on attaining puberty, is regarded as ceremonially impure and has to occupy a separate room for three days. At the end 'of this period a purificatory ceremony is performed, at which th'e girl has to leap, first over a leaf-plate containing boiled cakes and then across a line of burning charcoal spread on the ground. Food is given to a Dhobi and the ground which the girl may have occupied during the period of her impurity, is cleansed witJi cow-dung.

Widow-Marriage

A widow may marry again, but not her late husband's brother. The ritual in use at the marriage of a widow is simple and consists in presenting the widow with a new sari, glass bangles and toe-rings and tying the 'Tali' round her neck.

Divorce

Divorce is recognised on the ground of the wife's adultery or the husband's infidelity or inability to support her. The divorce is effected by the wife breaking a piece of straw in the pre- sence of the caste Pancha'sat as a symbol of separation. Divorced women are allowed to marry again and the ceremony is the same as that of a widow's marriage.

Inheritance

The Munnurs follow the Hindu Law of Inherit- ance and the sons share equally in their father's property. The tribal usage of Chudawand possesses full importance among them.

Child-Birth

A Munnur female in child-birth is unclean for ten days. On the birth of a child a pit is dug near the cot, in which all the impurities of parturition are buried. On the third day after birth the midwife keeps small stones on the brim of the pit, paints them with chunam and red lead and offers them food whicji she sub- sequently claims as her due. A sword is kept near the cot on which the mother is lying, avowedly for the purpose of warding off evil spirits. On the 11th or the 21 st day the woman has to daub tte brim of a well with kunkum-turmeric .powder and to draw water, whereupon her impurity ceases. ' <

Religion

In their religion the Mannurs differ very little from the other Telugu castes of the same social standing. They belong to both the Shaiva and Vaishnava sects and under the titles of Vibhuti- dharis and Tirmanidharis are followers of Aradhi and Shri-vaishnava Brahmans. In the religious and ceremonial observances Smartha Brahmans serve them as priests. At funeral ceremonies Satanis are engaged by Tirmanidharis and Jangams by Vibhutidharis.

The popular deities, Pochamma, Idamma, Maisamma, etc., are July appeased with animal offerings. The Munnurs are a ghost- ridden people and ascribe every disease or calamity to the influence of some malevolent spirit. Erkala and Erpula women are consulted as experts in identifying these airy forms which are, thereupon, pacified ivith various suitable offerings.

Raja Bhartrihari, the deified founder of the caste, is honoured before marriage. On the full moon day of Kartik (October) women worship 'Kedari Gauramma with offerings of sweets and flowers.

Disposal of the Dead

As a rule the Munnurs burn their dead in a lying posture with the head to the south. After death the body is washed and borne on a bier to the burning ground. Bodies of persons who die unmarried are, however, buried, being carried to the burial ground suspended on a bamboo pole and disposed of in a pit without any ceremony. Members of the caste who cannot afford to pay the cremation expenses also bury their dead. On the third day after death the ashes and bones are collected and thrown into a river by Vibhutidharis and are buried under a platform by Nam- dharis. On the same day fowls are sacrificed in the name of the deceased and the flesh is cooked by a Satani. A portion is thrown to the birds and the remainder , is partaken of by all the mourners. The period of mourning for adults is ten days and for children three days. The mother-in-law, paternal and maternal aunts, maternal uncles a-ad married daughters are mourned for three days. On the tenth day after death libations of water are offered to the deceased, represented by small stones. The ' Shradha ' ceremony is performed bnly once a year on the Pitra Amawcisya day (middle of September).

Social Status

The 'social rank of the Munnurs is much the same as that of Kapus, Reddis, Velammas and Gollas, with whom they exchange cooked food. They eat pork, fowls, lizards, mutton and fish of all varieties and indulge freely in spirituous and fermented liquors.

Occupation

Agriculture is said to be the original occupation of the caste and the bulk of them still cling to this. A few are village patels and have risen to high status as landlords and Zamindars; but the majority are ordinary cultivators, holding lands on permanent tenure. Some of them ar^ landless day-labourers and are employed as menial servants in rich families. A considerable portion of the Munnurs have, from reeent date, given up their original occupation and have either entered Government service or become traders. Members of this caste do not wear the sacred thread.

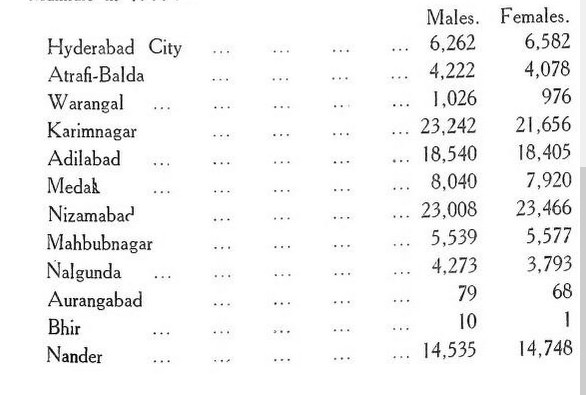

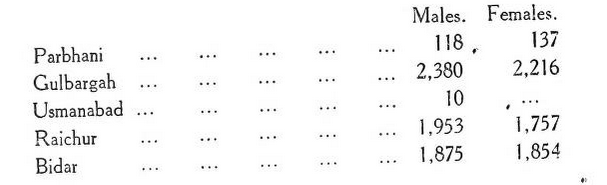

The following statement shows the number and distribution of Munnurs in 1911 :—