Muslims in Indian politics

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Lok Sabha

Uttar Pradesh

1999-2019

From: Anand Soondas, April 18, 2024: The Times of India

See graphic:

Muslim representation from Uttar Pradesh in the Lok Sabha, 1999-2019

Representation in state assemblies

Uttar Pradesh

1951- 2012

The Times of India

See graphic:

Community MLAs in Assembly, 2012 and muslim MLAs in UP Assembly, 1951-12

1994-2017

Parvez Iqbal Siddiqui, February 14, 2022: The Times of India

From: Parvez Iqbal Siddiqui, February 14, 2022: The Times of India

From: Parvez Iqbal Siddiqui, February 14, 2022: The Times of India

From: Parvez Iqbal Siddiqui, February 14, 2022: The Times of India

From: Parvez Iqbal Siddiqui, February 14, 2022: The Times of India

From: Parvez Iqbal Siddiqui, February 14, 2022: The Times of India

From: Parvez Iqbal Siddiqui, February 14, 2022: The Times of India

From: Parvez Iqbal Siddiqui, February 14, 2022: The Times of India

From: Parvez Iqbal Siddiqui, February 14, 2022: The Times of India

The support of the Muslim community, which accounts for more than 19% of UP’s population, was always considered crucial for any party to form a government. Until 2014.

That year, BJP reached out to OBC (other backward classes) and MBC (most backward classes) voters as a part of its targeted Hindu consolidation for the Lok Sabha polls. The minority vote was left marginalised electorally. Not one Muslim MP made it to the Lok Sabha.

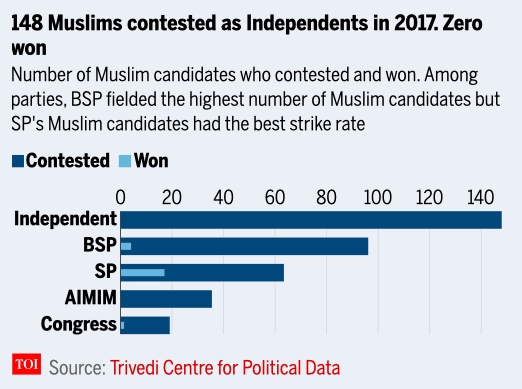

And by the next assembly election in 2017, the number of Muslim MLAs also dwindled to 25. It was a sharp drop from the 68 in 2012 — the highest ever in the UP assembly and, possibly, a polarising political talking point. This, when there are over 120 assembly constituencies out of the total of 403 which have a sizeable Muslim population – 20% or more. In Rampur, Muslims constitute more than 50% of the population. In Moradabad and Sambhal, it is 47%. Bijnor, Saharanpur, Muzaffarnagar, Shamli and Amroha, too, have over 40% Muslims. Five other districts have a Muslim population between 30% and 40%, and 12 districts have 20% to 30% Muslims.

What happened to the Muslim vote?

Despite its numerical strength, the community has seen that its strategy of backing the most powerful candidate to defeat the BJP nominee in each constituency has not worked in the three recent elections — 2014 Lok Sabha, 2017 assembly and 2019 Lok Sabha.

This time, political parties, perhaps as a way to stop counter-polarisation of Hindu voters, have been noticeably silent on Muslim issues. Whether it is fielding Muslim candidates or backing anti-Citizenship Amendment Act protests, non-BJP parties have been mostly silent. Samajwadi Party (SP), historically a strong supporter of Muslim welfare, is no longer showcasing how many Muslim candidates it has fielded so far.

Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) has moved its social engineering focus from the Dalit-Muslim combination to the Dalit-Brahmin alignment. None of the major opposition players has even come up with any community-specific promise in their manifestos. Political observers said that given the existing political circumstances silence might be “better than speech.”

Many Muslim voters think so, too. Instead of giving any handle to the BJP to polarise the election.

Uttar Pradesh, 2022

Pervez IqbalSiddiqui, February 14, 2022: The Times of India

From: Pervez IqbalSiddiqui, February 14, 2022: The Times of India

Lucknow: Once seen as the ‘deciding factor’ for their propensity for ‘strategic voting’, Muslims were a formidable electorate in UP until the 2014 general elections, when BJP’s strategy of consolidating Hindu votes across the state’s deep caste divide pushed the minority vote to the margins. Eight years and three major elections later, the Muslim ‘vote bank’ is quiet in 2022 — though the community that makes up more than 19% of UP’s population can still influence the outcome in over 120 of 403 assembly constituencies through its numerical strength. What was its strength became its weakness after 2014 when not a single Muslim MP from UP made it to the Lok Sabha. Over 120 seats have 20% or more people from the community, but the number of Muslim MLAs dwindled to 25 — from 68 in 2012, the highest ever in the UP assembly. Numbers matter, but not always. Muslims constitute more than 50% of Rampur’s population; 47% in Moradabad and Sambhal; 43% in Bijnor; 41% in Saharanpur; over 40% in Muzaffarnagar, Shamli and Amroha; between 30% and 40% in five more districts; and 20% to 30% in 12 districts. And yet, the community has acquired a mute-spectator image lately. This time it hopes things will change. The silence is not limited to the community. Political parties have been silent on ‘Muslim issues’— seen as a strategy to stop counter-polarisation of Hindu votes. Non-BJP parties have been quiet on a range of topics linked to the community: like openly backing antiCAA protests in UP that left over 20 dead, or fielding Muslim candidates. Samajwadi Party has not showcased how many Muslim candidates it has fielded, while Mayawati’s BSP has shifted its focus from Dalit-Muslim to Dalit-Brahmin alignment. None of the major opposition players have made any community specific promises in their manifestos.

Many Muslims see this silence as the right move to prevent further polarisation of votes. “This seems to be why BJP was unable to cling to communal issues such as Kabristan versus Shamshan that it did in the past. Had SP, BSP or Congress participated in the anti-CAA protests or the farmers’ protest, BJP would have politically blunted those agitations,” said Imran Asad, abusinessman from Bhadohi.

There’s something more, and Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind’s state head Maulana Ashhad Rashidi explained: “In a democracy like India, it is not about keeping a community together but ensuring that the secular vote remains undivided. ”

But it was this very ‘unity’ that singled out the community as a separate bloc — with singular problems. “This created an image that Muslims were being treated differently, though their problems were the same as the rest of the population,” said Maulana Khalid Rasheed Firangi Mahli, Imam of Lucknow’s biggest Eidgah at Aishbagh. “This time, Muslims are not being demarcated as a separate chunk, but as a homogeneous part of the electorate. That is excellent for a secular democracy,” the Maulana said.

Top Shia cleric Maulana Saif Abbas said the community has formed a UP Democratic Forum to persuade Muslim voters to go and vote. “In 2017, we found that the community’s voting percentage was less than 50%,” he said. The population in six of nine districts voting on February 14 are 30% from the community.

Voting pattern

2021: state assembly elections

May 5, 2021: The Times of India

Assembly Elections 2021: How Muslims voted in the state elections

When it comes to politics, especially electoral politics, the march of civilisation seems to pause if not stop. Votes are shought, and cast, not only on how many schools, roads or hospitals have been built in a constituency but also on how pro or anti a party and its candidate is seen towards a religion — or the followers of a faith.

The clearest evidence of this ‘should-have-no-place-in-modern-society’ feature of Indian elections is the discussion on polarisation of voters. Usually termed as polarisation between majority and minority (meaning Hindus and Muslims everywhere except in Jammu & Kashmir) votes, tracking this trend has become more significant since 2014 when the appeal for votes along religious identity has become more open.

The trend isn’t new. But instead of diluting over time, it has been intensifying at least in public debate. One rough way to measure the presence and extent of polarisation is to look at how different parties and alliances performed in constituencies where Muslims have a higher share in total population than their average share in the state.

Here’s what an analysis of the four states that went to polls recently shows.

Assam

Going by the results, the state was most polarised among the four where elections were held last month. The BJP-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA), perceived to be less minority-friendly, did not win a single seat in the 34 constituencies with sizable Muslim presence. Its vote share too was less than half (27%) of Congress-led UPA’s (62%)

Fortunes were reversed in the 92 constituencies where Muslim presence is insignificant. There, NDA grabbed 75 seats and 52% share of votes. Among states without a Muslim majority, Assam has the highest share of Muslims.

Of the total 126 seats in the Assam Assembly, NDA won 75 with 44.5% of votes polled, whereas UPA took 50 seats with 43.5% vote share. Other parties got 1 seat with 12% votes

Constituencies with significant share of Muslim voters are mostly in Barak Valley and in Lower Assam.

West Bengal

Compared to Assam, BJP seems to have done a shade better in parts of Bengal that have significant Muslim voters. The party won 21 of 141 such seats with a vote share of 35%. The Left-Congress-India Secular Front alliance that most overtly appealed for Muslim votes got one seat--it’s only win in the state. What is unclear from this quick and not-too-detailed analysis is the extent to which Hindu votes consolidated with BJP in these constituencies. In UP and Bihar, the party had won several seats in areas with significant Muslim population, most likely because Hindu votes went almost entirely to it. The phenomenon has been termed ‘reverse polarisation’ in some political analyses.

BJP’s vote share in places without significant Muslim voters was 6 percentage points higher (compare the two charts) allowing it to win a little over a third of the seats in such constituencies

Of the 292 seats in the Bengal Assembly, the Trinamool Congress (AITC) won 214 with 48.3% of votes going in its favour. BJP+ took 77 seats with 38% vote share. Left+Cong+ISF got 1 seat with 10% votes.

Constituencies with significant share of Muslim voters are not concentrated in any one or two areas of the state.

Tamil Nadu

This southern state has one of the lowest populations of Muslims in the country. Therefore, the constituencies studied here for possible polarisation included a relatively higher population of two minorities--Muslims and Christians.

Surface- level observation shows that the DMK-led alliance, which was considered more secular, scored significantly better in places with relatively higher minority voters by securing twice as many seats as the AIADMK alliance that had BJP as a partner.

In places where minority voters were insignificant, the AIADMK alliance narrowed the vote share gap significantly, though it won less than half the seats.

Of the total 234 seats in the TN Assembly, DMK+ won 159 grabbing 45.4% of votes polled. AIADMK+ took 75 seats with 39.7% vote share. All others got 15% votes, but no seats in the Assembly.

Constituencies with higher share of Muslim and Christian voters are scattered across the state.

Kerala

This state had the distinct feature of BJP not being part of two principal and traditionally strong alliances — the LDF and the UDF. So the dramatically different seat share of these two alliances in constituencies with significant Muslim population had little or nothing to do with Hindu-Muslim vote split.

What is perhaps mildly suggestive of polarisation is the difference in vote share of the NDA between areas with higher and lower number of Muslim voters. The BJP-led alliance did get a higher share of votes where minorities are not significant.

Of the total 140 seats in the Kerala Assembly, LDF won 99 with 45.3% share of votes. UDF won 41 seats with 39.4% of votes. Others got 15% votes, but didn't win a single seat.

North Kerala has significantly higher presence of Muslim voters than the southern region of the state.