Mysore State: People, 1909

This article was written between 1907- 1909 when conditions were Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles |

From Imperial Gazetteer of India, 1907 – 1909

Mysore State (Maisūr): 1909

Castes

The Hindus have been arranged under 72 castes or classes. Of these, the strongest numerically are Wokkaligas (1,287,000), Lingāyats (671,000), and Holeyas (596,000), who between them make up 46 per cent. of the total population. The Wokkaligas (in Hindustānī, Kunbī) are the cultivators or ryots. They include numerous tribes, some of Kanarese and some of Telugu origin, who neither eat together nor intermarry.

Their headmen are called Gaudas. Marriage is not always performed before puberty, and polygamy has some vogue, the industry of the women being generally profitable to the husband. Widow remarriage is allowed, but lightly esteemed. The Wokkaligas are mostly vegetarians and do not drink intoxicating liquor.

They bury their dead. The Gangadikāra, who form nearly one-half of the class, are purely Kanarese, found chiefly in the central and southern tracts. They represent the subjects of the ancient Gangavādi which formed the nucleus of the Ganga empire. At the present day they are [S. 194] followers some of Siva and some of Vishnu. Next in numbers are the Morasu Wokkaligas, chiefly in Kolār and Bangalore Districts. They appear to have been originally immigrants from a district called Morasu-nād, to the east of Mysore, whose chiefs formed settlements at the end of the fourteenth century in the parts round Nandidroog.

The section called Beralukoduva (' finger-giving ') had a strange custom, which, on account of its cruelty, was put a stop to by Government. Every woman of the sect, before piercing the ears of her eldest daughter preparatory to betrothal, had to suffer amputation of the ring and little fingers of the right hand, the operation being performed by the village blacksmith with a chisel.

The sacred place of the Morasu Wokkaligas is Sīti-betta in the Kolār tāluk, where there is a temple of Bhairava. Of other large tribes of Wokkaligas, the Sāda abound mostly in the north and west. They include Jains and Lingāyats, Vaishnavas and Saivas. Not improbably they all belonged originally to the first. In the old days many of them acted in the Kandāchār or native militia. They are not only cultivators but sometimes trade in grain. The Reddi are found chiefly in the east and north, and have numerous subdivisions.

To some extent they seem to be of Telugu origin, and have been supposed to represent the subjects of the ancient Rattavādi, or kingdom of the Rattas. The Nonabas, in like manner, are relics of the ancient Nolambavādi or Nonambavādi, a Pallava province, situated in Chitaldroog District. At the present day they are by faith Lingāyats, the residence of their chief guru being at Gaudikere near Chiknāyakanhalli. The acknowledged head of the Nonabas lives at Hosahalli near Gubbi. The Halepaiks of the Nagar Malnād are of special interest as being probably aboriginal.

Their name is said to mean the 'old foot,' as they furnished the foot-soldiers and body-guards of former rulers, to whom they were noted for their fidelity. Their principal occupation now is the extraction of toddy from the bagni-palm (Caryota urens), the cultivation of rice land, and of kāns or woods containing pepper vines ; but they are described as still fond of firearms, brave, and great sportsmen. In Vastāra and Tuluva (South Kanara) they are called Billavas or 'bowmen.' In Manjarābād they are called Devara makkalu, 'God's children.' The Hālu Wokkaligas are mostly in Kadūr and Hassan Districts.

They are dairymen and sell milk (hālu) whence their name, as well as engage in agriculture. The Hallikāra are also largely occupied with cattle, the breed of their name being the best in the Amrit Mahāl. The Lālgonda, chiefly found in Bangalore District, not only farm, but hire out bullocks, or are gardeners, builders of mud walls, and traders in straw, &c. The Vellāla are the most numerous class of Wokkaligas in the Civil and Military Station of Bangalore. Another large class, as numerous as the Reddi, are the Kunchitiga, widely spread but mostly found in the [S. 195] central tracts. The women prepare and sell dāl (pigeon pea), while the men engage in a variety of trades.

The Holeyas (Tamil, Paraiya ; Marāthī, Dhed) are outcastes, occupying a quarter of their own, called the Holageri, outside every village boundary hedge. They are indigenous and probably aboriginal. They have numerous subdivisions, which eat together but only intermarry between known families.

A council of elders decides all questions of tribal discipline. They are regarded as unclean by the four principal castes, and particularly by the Brāhmans. In rural parts especially, a Holeya, having anything to deliver to a Brāhman, places it on the ground and retires to a distance, and on meeting a Brāhman in the road endeavours to get away as far as possible. Brāhmans and Holeyas mutually avoid passing through the parts they respectively occupy in the villages ; and a wilful transgression in this respect, if it did not create a riot, would make purification necessary, and that for both sides.

They often take the vow to become Dāsari, and regard the Sātāni as priests, but a Holeya is himself generally the priest of the village goddess. Under the name of Tirukula, the Holeyas have the privilege of entering the great temple at Melukote once a year to pay their devotions, said to be a reward for assisting Rāmānuja to recover the image of Krishna which had been carried off to Delhi by the Musalmāns. The Holeya marriage rite is merely a feast, at which the bridegroom ties a token round the bride's neck. A wife cannot be divorced except for adultery. Widows may not remarry, but often live with another man.

The Holeyas eat flesh and fish of all kinds, and even carrion, provided the animal died a natural death, and drink spirituous liquors. As a body the Holeyas are the servants of the ryots, and are mainly engaged in following the plough and watching the herds. They also make certain kinds of coarse cloth, worn by the poorer classes. The Alemān section furnishes recruits for the Barr sepoy regiments. In the Maidān a Holeya is the kulavādi, and has a recognized place in the village corporation. He is the village policeman, the beadle, and the headman's factotum. The kulavādis are the ultimate referees in cases of boundary disputes, and if they agree no one can challenge the decision.

In the Malnād the Holeya was merely a slave, of which there were two classes : the huttāl, or slave born in the house, the hereditary serf of the family ; and the mannāl, or slave of the soil, who was bought and sold with the land. Now these have of course been emancipated, and some are becoming owners of land. In urban centres they are rising in respectability and acquiring wealth, so that in certain cases their social disabilities are being overcome, and in public matters especially their complete ostracism cannot be maintained.

Ten other castes, each above 100,000, make up between them 30 [S. 196] per cent. of the population. They are the Kuruba (378,000), Mādiga (280,000), Beda or Bedar (245,000), Brāhman (190,000), Besta (153,000), Golla (143,000), Wodda (135,000), Banajiga (123,000), Panchāla (126,000), and Uppāra (106,000). The Kurubas are shepherds and weavers of native blankets (kambli).

There is no intercourse between the general body and the division called Hande Kurubas. The former worship Bire Deva and are Saivas, their priests being Brāhmans and Jogis. The caste also worship a box, which they believe contains the wearing apparel of Krishna, under the name of Junjappa. Parts of Chitaldroog and the town of Kolār are noted for the manufacture by the Kurubas there of a superior woollen of fine texture like homespun.

The women spin wool, and as they are very industrious, polygamy prevails, and even adultery is often condoned, their labour being a source of profit. The wild or Kādu Kurubas (8,842) are subdivided into Betta or 'hill,' and Jenu or 'honey,' Kurubas. The former are a small and active race, expert woodmen, and capable of enduring great fatigue. The latter are a darker and inferior race, who collect honey and beeswax.

Their villages or clusters of huts are called hadi; and a separate hut is set apart at one end for the unmarried females to sleep in at night, and one at the other end for the unmarried males, both being under the supervision of the headman. Girls are married only after puberty, either according to the Wokkaliga custom, or by a mere formal exchange of areca-nut and betel-leaf. Polygamy exists, but the offspring of concubines are not considered legitimate. All kinds of meat except beef are eaten, but intoxicating drinks are not used. In case of death, adults are cremated and children buried.

The Betta Kurubas worship forest deities called Norāle and Māstamma, and are said to be revengeful, but if treated kindly will do willing service. The Jenu Kurubas neither own nor cultivate land for themselves, nor keep live-stock of their own. Both classes are expert in tracking wild animals, as well as skilful in eluding pursuit by wild animals accidentally encountered. Their children when over two years old move about freely in the jungle.

The Mādigas are similar to the Holeyas, but distinguished from them by being workers in leather. They remove the carcases of dead cattle, and dress the hides to provide the villagers with leathern articles, such as the thongs for bullock yokes, buckets for raising water, &c. They are largely engaged in field labour, and in urban centres are earning much money, owing to the increasing demand for hides and their work as tanners. They worship Vishnu, Siva, and their female counterparts or Saktis, and have five different gurus or maths in the State.

They have a division called Desabhāga, who do not intermarry with the others. They acknowledge Srīvaishnava Brāhmans as their gurus, and have also the names Jāmbavakula and Mātanga. They are [S. 197] privileged to enter the courtyard of the Belūr temple at certain times to present the god with a pair of slippers, which it is the duty of those in Channagiri and Basavāpatna to provide. Their customs are much the same as those of the Holeyas.

The Bedas (Bedar), or Naiks, are both Kanarese and Telugu, the two sections neither eating together nor intermarrying. One-third are in Chitaldroog District, and most of the rest in Kolār and Tumkūr. They were formerly hunters and soldiers by profession, and largely composed Haidar's and Tipū's infantry. Many of the M)sore poligārs were of this caste. They now engage in agriculture, and serve as police and revenue peons.

They claim descent from Vālmīki, author of the Rāmāyana, and are chiefly Vaishnavas, but worship all the Hindu deities. In some parts they erect a circular hut for a temple, with a stake in the middle, which is the god. In common with the Golla, Kuruba, Mādiga, and other classes, they often dedicate as a Basavi or prostitute the eldest daughter in a family when no son has been born ; and a girl falling ill is similarly vowed to be left unmarried, i.e. to the same fate. If she bear a son, he is affiliated to her father's family. Except as regards beef, they are not restricted in food or drink.

Polygamy is not uncommon, but divorce can be resorted to only in case of adultery. Widows may not remarry, but often live with another Beda. The dead are buried. The caste often take the vow to become Dāsari. Their chief deity is the god Venkataramana of Tirupati, locally worshipped under the name Tirumala, but offerings and sacrifices are also made to Māriamma.

Their guru is known as Tirumala Tatāchārya, a head of the Srīvaishnava Brāhmans. The Māchi or Myāsa branch, also called Chunchu, circumcise their boys at ten or twelve years of age, besides initiating them with Hindu rites. They eschew all strong drink, and will not even touch the date-palm from which it is extracted.

They eat beef, but of birds only partridge and quail. Women in childbirth are segregated. The dead are cremated, and their ashes scattered on tangadi bushes (Cassia auriculata). This singular confusion of customs may perhaps be due to the forced conversion of large numbers to Islam in the time of Haidar to form his Chela battalions. The Telugu Bedas are called Boya. One section, who are shikris, and live on game and forest produce, are called Myāsa or Vyādha. The others are settled in villages, and live by fishing and day labour. The latter employ Brāhmans and Jangamas as priests, but the former call in elders of their own caste. The Myāsa women may not wear toe-rings, and the men may not sit on date mats.

Bestas are fishermen, boatmen, and palanquin-bearers. This is their name in the east; in the south they are called Toreya, Ambiga, and Parivāra ; in the west Kabyara and Gangemakkalu. Those who speak Telugu call themselves Bhoyi, and have a headman called Pedda [S. 198] Bhoyi. One section are lime-burners. Some are peons, and a large number engage in agriculture.

Their domestic customs are similar to those of the castes above mentioned. Their goddess is Yellamma, and they are mostly worshippers of Siva. They employ Brāhmans and Sātānis for domestic ceremonies. The Gollas are cowherds and dairymen. The Kādu or 'forest' Gollas are distinct from the Uru or 'town' Gollas, and the two neither eat together nor intermarry. One section was formerly largely employed in transporting money from one part of the country to another, and gained the name Dhanapāla. One of the servants in Government treasuries is still called the Golla.

They worship Krishna as having been born in their caste. The Kādu Gollas are nomadic, and live in thatched huts outside the villages. At childbirth the mother and babe are kept in a small hut apart from the others for from seven to thirty days. If ill, none of her caste will attend on her, but a Naik or Beda woman is engaged to do so. Marriages are likewise performed in a temporary shed outside the village, to which the wedded pair return only after five days of festivity. Golla women do not wear the bodice, nor in widowhood do they break off their glass bangles. Remarriage of widows is not allowed.

The Woddas are composed of Kallu Woddas and Mannu Woddas, between whom there is no social intercourse or intermarriage. The Kallu Woddas, who consider themselves superior to the others, are stonemasons, quarrying, transporting, and building with stone, and are very dexterous in moving large masses by simple mechanical means.

The Mannu Woddas are chiefly tank-diggers, well-sinkers, and generally skilful navvies for all kinds of earthwork, the men digging and the women removing the earth. Though a hard-working class, they have the reputation of assisting dacoits and burglars by giving information as to plunder. The young and robust of the Mannu Woddas of both sexes travel about in caravans in search of employment, taking with them their infants and huts, which consist of a few sticks and mats. On obtaining any large earthwork, they form an encampment in the neighbourhood.

The older members settle in the outskirts of towns, where many of both .sexes now find employment in various kinds of sanitary work. They were probably immigrants from Orissa and the Telugu country, and generally speak Telugu. They eat meat and drink spirits, and are given to polygamy. Widows and divorced women can remarry. Both classes worship all the Hindu deities, but chiefly Vishnu.

The Banajigas are the great trading class. The subdivisions are numerous, but there are three main branches— the Panchama, Telugu, and Jain Banajigas— who neither eat together nor intermarry. The first are Lingāyats, having their own priests, who officiate at marriages [S. 199] and funerals, and punish breaches of caste discipline. Telugu Banajigas are very numerous. The Saivas and Vaishnavas among them do not intermix socially.

The latter acknowledge the guru of the Srīvaishnava Brāhmans. They frequently take the vow to become Dāsari. Many dancing-girls are of this caste. The Panchāla, as their name implies, embrace five guilds of artisans : namely, goldsmiths, brass and coppersmiths, blacksmiths, carpenters, and sculptors. They wear the triple cord and consider themselves equal to the Brāhmans, who, however, deny their pretensions. The goldsmiths are the recognized heads of the clan.

The Panchāla have a guru of their own caste, though Brāhmans officiate as purohits. The Uppāra are saltmakers. This is their name in the east ; in the south they are called Uppaliga, and in the west Melusakkare. There are two classes, Kannada and Telugu. The former make earth-salt, while the latter are bricklayers and builders. They are worshippers of Vishnu and Dharma Rāya.

The agricultural, artisan, and trading communities form a species of guilds called phana (apparently a very ancient institution), and these are divided into two factions, termed Balagui (right-hand) and Yedagai (left-hand). The former contains 18 phana, headed by the Banajiga and Wokkaliga, with the Holeya at the bottom ; while the latter contains 9 phana, with the Panchāla and Nagarta (traders) at the head, and the Mādiga at the bottom. Brāhmans, Kshattriyas, and most of the Sūdras are considered to be neutral. Each party insists on the exclusive right to certain privileges on all public festivals and ceremonies, which are jealously guarded. A breach on either side leads to faction fights, which formerly were of a furious and sometimes sanguinary character.

Thus, the right-hand claim the exclusive privilege of having 12 pillars to the marriage pandal, the left-hand being restricted to 11; of riding on horseback in processions, and of carrying a flag painted with the figure of Hanuman. In the Census of 1891 the people by common consent repudiated the names Balagai and Yedagai, and preferred to return themselves as of the 18 phana or the 9 phana. In the Census of 1901 even this distinction was ignored, and the people returned themselves in various irreconcilable ways, mostly as belonging to the 12 phana. The old animosity of the factions seems to be wearing away.

Of nomad tribes, more than half are Lambānis and another fourth are Koracha, Korama, or Korava. The first are a gipsy tribe that wander about in gangs with large herds of bullocks, transporting grain and other produce, especially in the hilly and forest tracts. Of late years some have been employed on coffee estates, and some have even partially abandoned their vagrant life, and settled, at least for a time, in villages of their own.

These, called tāndas, are composed of groups [S. 200] of their usual rude wicker huts, pitched on waste ground in wild places. The women bring in bundles of firewood from the jungles for sale in the towns. The Lambānis speak a mixed dialect called Kutnī largely composed of Hindī and Marāthī corruptions. The women are distinguished by a picturesque dress different from that worn by any other class. It consists of a sort of tartan petticoat, with a stomacher over the bosom, and an embroidered mantle covering the head and upper part of the body. The hair is worn in ringlets or plaits, hanging down each side of the face, decorated with small shells, and ending in tassels.

The arms and ankles are profusely covered with trinkets made of bone, brass, and other rude materials. The men wear tight cotton breeches, reaching a little below the knee, with a waistband ending in red silk tassels, and on the head a small red or white turban.

There is a class of Lambāni outcastes, called Dhālya, who are drummers and live separately. They chiefly trade in bullocks. The Lambānis hold Gosains as their gurus, and reverence Krishna ; also Basava, as representing the cattle that Krishna tended. But their chief object of worship is Banashankarī, the goddess of forests. Their marriage rite consists of mutual gifts and a tipsy feast. The bridal pair also pour milk down an ant-hill occupied by a snake, and make offerings to it of coco-nuts and flowers. Polygamy is in vogue, and widows and divorced women may remarry, but with some disabilities.

The Lambānis are also called Sukāli and Brinjāri. The Koracha, Korama, or Korava are a numerous wandering tribe, who carry salt and grain from one market to another by means of large droves of cattle and asses, and also make bamboo mats and baskets. The men wear their hair gathered up into a big knot or bunch on one side of the top of the head, resembling what is seen on ancient sculptured stones. The women may be known by numerous strings of small red and white glass beads and shells, worn round the neck and falling over the bosom.

In the depths of the forest they are even said to dispense with more substantial covering. A custom like couvade is said to linger among the Korava, but this is not certain. The dead are buried at night in out-of-the-way spots. The women are skilful in tattooing. The Iruliga are the remaining wild tribe, and include the Sholaga, who live in the south-east in the Biligiri-Rangan hills.

They are very dark, and are keen-sighted and skilful in tracking game. They cultivate small patches of jungle clearings with the hoe, on the kumri or shifting system. Polygamy is the rule among them, and adultery is unknown. When a girl consents to marriage, the man runs away with her to some other place till the honeymoon is over, when they return home and give a feast. They live in bamboo huts thatched with plantain leaves.

Languages

The distinctive language of Mysore is Kannada, the Karnāta or Karnātaka of the pandits, and the Kanarese of European writers. It is the speech of 73 per cent. of the population, and prevails everywhere except in the east. Telugu, confined to Kolār District and some of the eastern tāluks, is the language of 15 per cent. Tamil (called here Arava) is the speech of 4 per cent., and predominates at the Kolār Gold

Fields and among the servants of Europeans, camp-followers, and cantonment traders. A more or less corrupt Tamil is spoken by certain long-domiciled classes of Brāhmans (Srīvaishnava, Sanketi, and Brihachcharana), and by Tigala cultivators, but its use is only colloquial.

Marāthī, which is spoken by 1.4 per cent. of the population, is the language of Deshasth Brāhmans and Darzis or tailors, the former being most numerous in Shimoga District. Hindustānī, the language of Musalmāns, who form 5.22 per cent. of the population, is spoken by only 4.8 per cent., the difference being due to the Labbais and other Musalmāns from the south who speak Tamil.

In each of these vernaculars there has been since 1891 an increase of about 11 per cent., except in Tamil, which has increased 42 per cent., owing to the influx of labour at the gold-mines and partly on the railways.

Religious communities

The percentage of the followers of each religion to the whole population [S. 201] at the Census of 1901 was, in order of strength : Hindus, 92.1 ; Musalmāns, 5.2 ; Animists, 1.6 : Christians, 0.9 ; Jains, 0.2. There remained 158 persons who were Parsis, Sikhs, Jews, Brahmos, or Buddhists : 101 were Parsis and 34 Jews. The percentage of increase in each religion since 1891 was: Christians, 31.3: Musalmāns, 14.5; Hindus, 11.5; Jains, 3.

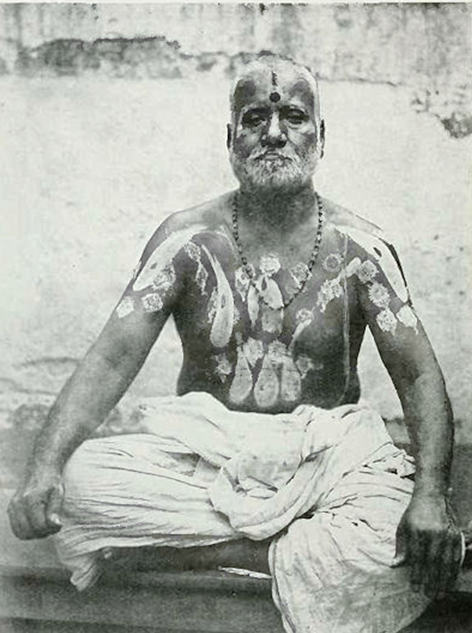

Of Hindu religious sects in Mysore, Lingāyats are by far the strongest in numbers ; and if, in addition to those returned as such, the Nonaba, Banajiga, and others belonging to the sect be taken into account, they cannot be much below 800,000. Their own name for themselves is Sivabhakta or Sivāchr, and Vīra Saiva. Their distinctive mark is the wearing of a jangama (or portable) lingam on the person, hence the name Lingāyata or Lingavanta.

The lingam is a small stone, about the size of an acorn, enshrined in a silver casket of peculiar shape, worn suspended from the neck or bound to the arm. They also mark the forehead with a round white spot. The clerics smear their faces and bodies with ashes, and wear garments of the colour of red ochre, with a rosary of rudrksha beads round the neck.

Phallic worship is no doubt one of the most ancient and widely diffused forms of religion in the world, and the Lingāyats of late have made doubtful pretensions to date as far back as the time of Buddha. Among the Saiva sects mentioned by the reformer Sankarāchārya as existing in India in the eighth century were the Jangamas, who he says wore the trident on the head and carried a lingam made of stone on their persons, and whom he denounces as unorthodox. Of this sect the Lingāyats claim to be the representatives. Whether this be so or not, it is undoubted that the Lingāyat faith has been the popular creed of the Kanarese-speaking countries from the twelfth century.

Lingāyats reject the authority of Brāhmans and the inspiration of the Vedas, and deny the efficacy of sacrifices and srāddhas. They profess the Saiva faith in its idealistic form, accepting as their principal authority a Saiva commentary on the Vedānta Sūtras. They contend that the goal of karma or performance of ceremonies is twofold—the attainment of svarga or eternal heavenly bliss, and the attainment of jnāna or heavenly wisdom. The former is the aim of Brāhman observances ; the latter, resulting in union with the deity, is the summum bonum of the Lingāyats.

The Lingāyat sect in its present form dates from about 1160, a little more than forty years after the establishment of the Vaishnava faith and the ousting of the Jains in Mysore by Rāmānujāchārya. Its institution is attributed to Basava, prime minister of the Kalachuri king Bijjala, who succeeded the Chālukyas and ruled at Kalyāni (in the Nizām's Dominions) from 1155 to 1167. Basava (a vernacular form of the Sanskrit vrishabha, 'bull') was supposed to be an incarnation [S. 202] of Siva's bull Nandī, sent to the earth to revive the Saiva religion. He was the son of an Arādhya Brāhman, a native of Bāgevādi in Bijāpur District.

He refused to be invested with the sacred thread, or to acknowledge any guru but Siva, and incurred the hostility of the Brāhmans. He retired for some time to Sangamesvara, where he was instructed in the tenets of the Vīra Saiva faith. Eventually he went to Kalyāni, where the king Bijjala, who was a Jain, married his beautiful sister and made him prime minister. This position of influence enabled him to propagate his religious system. Meanwhile, a sister who was one of his first disciples had given birth to Channa Basava, supposed to be an incarnation of Siva's son Shanmukha, and he and his uncle are regarded as joint founders of the sect.

The Basava Purāna and Channa Basava Purāna, written in Hala Kannada, though not of the oldest form, containing miraculous stories of Saiva gurus and saints, are among their chief sacred books. Basava's liberal use of the public funds for the support of Jangama priests aroused the king's suspicions, and he thoughtlessly ordered two pious Lingāyats to be blinded, which led to his own assassination. Basava and Channa Basava fled from the vengeance of his son, and are said to have been absorbed into the god.

The reformed faith spread rapidly, superseding that of the Jains ; and according to tradition, within sixty years of Basava's death, or by 1228, it was embraced from Ulavi, near Goa, to Sholāpur, and from Bālehalli (in Kadūr District) to Sivaganga (Bangalore District). It was a State religion of Mysore from 1350 to 1610, and especially of the Keladi, Ikkeri, or Bednūr kingdom from 1550 to 1763, as well as of various neighbouring principalities. Since the decline of the Jains, the Lingāyats have been preservers and cultivators of the Kanarese language.

The sect was originally recruited from all castes, and observances of caste, pilgrimage, fasts, and penance were rejected. Basava taught that all holiness consisted in regard for three things, guru, lingam, and jangam—the guide, the image, and the fellow religionist. But caste distinctions are maintained in regard to social matters, such as intermarriage. The lingam is tied to an infant at birth, must always be worn to the end of life, and is buried with the dead body. At a reasonable age the child is initiated by the guru into the doctrines of the faith. All are rigid vegetarians. Girls are married before puberty. Widows do not marry again.

The dead are buried. The daily ritual consists of Saiva rites, and it may be stated that lingam worship, in both act and symbol, is absolutely free from anything indecorous. Five spiritual thrones or simhāsanas were originally established : namely, at Bālehalli (Kadūr District), Ujjain, Kāsī (Benares), Srīsailam (Kurnool District), and Kedārnāth (in the Himālayas). Maths still exist in these places and exercise jurisdiction over their respective spheres. [S. 203]

The Lingāyats are a peaceful and intelligent community, chiefly engaged in trade and agriculture. In commerce they occupy a very prominent place, and many are now taking advantage of the facilities for higher education and qualifying for the professions.

The Brāhmans (190,050) are divided among four sects : namely, Smartas, who form 63 per cent.; Mādhvas, 23 per cent.; Srīvaishnavas, 10 per cent.; and Bhāgavatas, 4 per cent.

•Smartas are followers of the smriti, and hold the Advaita doctrine. Their chief deity is Siva, and the sect was founded by Sankarāchārya in the eighth century. Their guru is the head of the math established by him at Sringeri (Kadūr District), who is styled the Jagad Guru. They are distinguished by three parallel horizontal lines of sandal paste or cow-dung ashes on the forehead, with a round red spot in the centre.

•The Mādhvas are named after their founder Madhvāchārya, who lived in South Kanara in the thirteenth century. They especially worship Vishnu, and hold the Dvaita doctrine. Their gurus are at Nanjangūd, Hole-Narsipur, and Sosile. They wear a black perpendicular line from the junction of the eyebrows to the top of the forehead, with a dot in the centre.

•The Srīvaishnavas worship Vishnu as identified with his consort Srī, and hold the Visishtādvaita doctrine. The sect was founded by Rāmānujāchārya early in the twelfth century. There are two branches :

•The Vadagalai ('northerners'), who form two-thirds, and adhere to the sacred texts in Sanskrit;

Oand the Tengalai ('southerners'), who form one-third, and have their sacred texts in Tamil.

Their mark is a trident on the forehead, the centre line being yellow or red and the two outer ones white. The Tengalai continue the central line of the trident in white for some distance down the nose.

•The Bhāgavatas are probably a very ancient sect. They are classed with Smartas, but chiefly worship Vishnu, and wear Vaishnava perpendicular marks. Nearly all the Brāhmans in Mysore belong to the Pancha Dravida or 'five tribes of the south.'

The Sātāni (22,378) are the next most numerous religious sect. They are regarded as priests by the Holeya and other inferior castes, and themselves have the chiefs of the Srīvaishnava Brāhmans and Sannyāsis as their gurus. They are votaries of Vishnu, especially in the form of Krishna, and are followers of Chaitanya. As a rule they are engaged in the service of Vaishnava temples, and are flower-gatherers, torch-bearers, and strolling musicians. They call themselves Vaishnavas, the Baisnabs of Bengal.

Of Musalmāns the majority are Sunnis, very few being Shiahs. There are thirteen Musalmān classes, the most numerous of which are Shaikh (178,625), Saiyid (42,468), Pathān (41,156), Mughal (8,241), Labbai (6,908), and Pinjari (4,558). The first four are mostly in the army, police, and other Government service, but many are merchants [S. 204] and traders. The Labbai are descendants of Arabs and women of the country.

They come from Negapatam and other parts of the Coromandel coast, and speak Tamil. They are an enterprising class of traders, settled in most of the towns, vendors of hardware and other articles, collectors of hides, and traders in coffee ; but they take up any lucrative business. Some are settled as agriculturists at Gargeswari in Mysore District. The Māppilla or Moplah are of similar origin but from the Malabar coast, and speak Malayālam.

They are principally on the coffee plantations in the west. At one time there were many at the Kolār gold-mines. The Pinjari are cotton-ginners and cleaners ; other Musalmāns as a rule have no intercourse with them. At Channapatna and one or two other places is a sect called Daire, who came originally from Hyderābād. They believe the Mahdi to have come and gone, and do not intermarry with other Musalmāns. They trade in silk with the West Coast.

Christians at the Census of 1901 numbered 50,059: namely, Europeans, 4,753; Eurasians, 5,721; and native Christians, 39,585. The first two classes are mostly in Bangalore and the Kolār Gold Fields, but they are also scattered in various parts of the country. European coffee-planters reside in Kadūr and Hassan Districts.

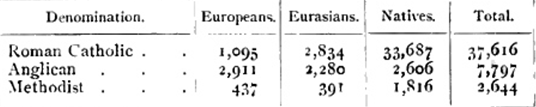

The principal Eurasian rural settlement is Whitefield in Bangalore District. The same District and the Kolār Gold Fields contain the largest number of native Christians. They have increased by 41.6 per cent. since 1891, or, excluding the Civil and Military Station of Bangalore, by 62.8 per cent. The following were the principal denominations returned :—

The Roman Catholics increased by 29 per cent. in the decade. As regards the Anglicans and Methodists, it appears that some belonging to the latter denomination entered themselves merely as Protestants, and were thereby included among the former. Putting both together, to rectify the error in some degree, the increase was 25.3 per cent.

The Methodists include Wesleyans and American Methodist Episcopalians. The Roman Catholic diocese of Mysore extends over Mysore, Coorg, Wynaad, Hosūr, and Kollegāl. The Bishop resides at Bangalore. The Anglican churches are in the diocese of the Bishop of Madras.

Of Christian missions to Mysore, the oldest by far was the Roman Catholic. So far back as 1.525 the Dominicans are said to have commenced work in the Hoysala kingdom. In 1400 they built a church [S. 205] at Anekal1. The Vijayanagar Dīwān in 1445 is said to have been a Christian, and also the viceroy at Seringapatam in 1520. In 1587 the Franciscans arrived on the scene.

But it was not till the middle of the seventeenth century that mission work was firmly established. At that period some Jesuit priests from Coimbatore founded the Kanarese Mission at Satyamangalam, Seringapatam, and other places in the south. In 1702 two French Jesuits from Vellore founded a Telugu mission in the east, building chapels at Bangalore, Devanhalli, Chik-Ballāpur, and other places.

The suppression of the Jesuit Order in 1773 was a severe check; and in the time of Tipū all the churches and chapels were razed to the ground, except one at Grāma near Hassan, and one at Seringapatam, the former being preserved by a Muhammadan officer, and the latter defended by the native Christian troops under their commander.

After the fall of Seringapatam in 1799 the work was taken up by the Foreign Missions Society of Paris, and the Abbé Dubois, who was in the south, was invited to Seringapatam by the Roman Catholics. He laboured in Mysore for twenty-two years, adopting the native dress and mode of living. He was highly respected by the people, who treated him as a Brāhman, and he became well-known from his work on Hindu Manners, &c., the manuscript of which was bought by the British Government2.

He was the founder of the church at Mysore, and of the Christian agricultural community of Sathalli near Hassan, and is said to have introduced vaccination into the State. The East India Company gave him a pension, and he died in France in 1848 at the age of eighty-three. In 1846 a Vicar Apostolic was appointed, and in 1887 Mysore was made a Bishopric.

The Roman Catholics have 98 places of worship in the State. At Bangalore they maintain a high-grade college and college classes for girls, a convent with schools, a well-equipped hospital, orphanages and Magdalen asylum, and a Home for the Aged under the Little Sisters of the Poor ; and at Mysore there are a convent and various schools. Agricultural farms for famine orphans have been formed in the tāluks bordering on Bangalore.

1 An old inscription, surmounted by a cross, has been found there relating to the kumbāra ane or potters' dam,

2 The best and most authentic edition of this work was published at Oxford in 1897, edited by the late H. K. Beauchamp.

Of Protestant missions the first to the Kanarese people was that at Bellary established by the London Missionary Society, which in 1820 was extended to Bangalore. The first dictionaries of the language, and the first translation of the Bible into the vernacular, together with the first casting of Kanarese type for their publication, were the work of this mission. They were also the pioneers of native female education, in 1840. They have Kanarese and Tamil churches at Bangalore, [S. 206] a high school, and various schools for girls. The out-stations are to the east and north of Bangalore, the chief being at Chik-Ballāpur.

The Wesleyan Mission began work in 1822, but only in Tamil, in the cantonment of Bangalore. Their Kanarese mission was commenced in 1835. In 1848 a great impetus was given to the publication of vernacular literature by their establishment of a printing press at Bangalore, and the vast improvements introduced in Kanarese type. The mission has now about forty circuits in Bangalore, Mysore, and the principal towns, with high schools at those cities, and numerous vernacular schools all over the country, besides hospitals for women and children at Mysore and Hassan.

They also have some industrial schools, and issue a Kanarese newspaper and magazine. The Church of England has a native S.P.G. mission at Bangalore, taken over in 1826 from the Danish Lutherans, by whom it had been begun a few years earlier; and the Zanāna Mission of the Church has a large Gosha hospital (for women) there, with a branch hospital at Channapatna, and a station at Mysore city.

The American Methodist Episcopal Church began work in 1880, and has places of worship and schools in Bangalore, chiefly for Eurasians, and a native industrial school at Kolār. A Leipzig Lutheran mission was established at Bangalore on a small scale in 1873 ; and there is a small Faith mission at Malavalli in Mysore District.