Nadia District, 1908

Contents |

Nadia District, 1908

District in the Presidency Division, Bengal, lying between 22° 53' and 24° 11' N. and 88° 9' and 89° 22' E., with an area of 2,793 square miles. It is bounded on the west by the BhagTrathi, or Hooghly river ; on the south by the Twenty-four Parganas ; on the north the Jalangl river separates it from Murshid- abad, and the Padma or main channel of the Ganges from Rajshahi and Pabna ; Farldpur and Jessore Districts form the eastern boundary.

Physical aspects

Nadia is situated at the head of the Gangetic delta, and its alluvial surface, though still liable in parts to inundation, has been raised by ancient deposits of silt above the normal flood- level; its soil agriculturally classed as high land,- and bears cold-season crops as well as rice. The rivers have now ceased their work of land-making and are beginning to silt up. The general aspect is that of a vast level alluvial plain, dotted with villages and clusters of trees, and intersected by numerous rivers, backwaters, minor streams, and swamps. In the west of the District is the Kalantar, a low-lying tract of black clay soil which stretches from the adjoining part of Murshidabad through the Kaliganj and Tehata thanas.

Along the northern boundary flows the wide stream of the Padma. This is now the main channel of the Ganges, which has taken this course in comparatively recent times ; it originally flowed down the BhagTrathi, still the sacred river in the estimation of Hindus, and it afterwards probably followed in turn the course of the Jalangi and the Matabhanga before it eventually took its present direction, flowing almost due east to meet the Brahmaputra near Goalundo. The rivers which intersect the District are thus either old beds of the Ganges or earlier streams, like the Bhairab, which carried the drainage of the Darjeeling Himalayas direct to the sea before the Padma broke eastwards and cut them in halves. The whole District is a network of moribund rivers and streams ; but the BhagTrathi, the Jalangi, and the Matarhanga are the three which are called distinctively the 'Nadia Rivers.' The Jalangi flows past the head-quarters station of Krislinagar, and falls into the BhagTrathi oi)posite the old town of Nadia. Its chief distributary is the Bhairab. The Matabhans;a, after throwing off the Pangasi, Kumar, and Kabadak, bifurcates near Krishnaganj into the Churni and IchamatT, and thereafter loses its own name. Marshes abound.

The surface consists of sandy clay and sand along the course of the rivers, and fine silt consolidating into clay in the flatter parts of the plain. The swamps afford a foothold for numerous marsh species, while the ponds and ditches are filled with submerged and floating water- plants. The edges of sluggish creeks are lined with large sedges and bulrushes, and the banks of rivers have a hedge-like shrub jungle. Deserted or uncultivated homestead lands are densely covered with shrubberies of semi-spontaneous species, interspersed with clumps of planted bamboos and groves of Areca, Mori?iga, Mangifera, and Anona ; and the slopes of embankments are often well wooded. Wild hog are plentiful, and snipe abound in the swamps. There are still a few leopards, and wild duck are found in the jhils near the Padma. Snakes are common and account for some 400 deaths annually ; about 90 more are caused by wild animals.

The mean temperature for the year is 79°, ranging between 69° and 88°. The mean minimum varies from 52° in January to 79° in June, and the mean maximum from 77° in December to 97° in May. The average humidity is 79 per cent, of saturation, varying from 71 per cent, in March to 87 per cent, in August. The annual rainfall averages 57 inches, of which 6'5 inches fall in May, 9-7 in June, 10-5 in July, 11-3 in August, S-i in September, and 4-1 in October.

Floods occur frequently and cause much damage ; the area especially liable to injury is a low-lying strip of land, about 10 miles wide, running in a south-easterly direction across the centre of the Dis- trict. It is said that this is swept by the floods of the Bhagirathi whenever the great Lalitakuri embankment in Murshidabad District gives way, but it is on record that the breaking of this embank- ment has not always been followed by a rise of the flood-level in Nadia.

History

The town of Nadia or Nabadwip (meaning 'new island'), from which the District takes its name, has a very ancient history, and about the time of William the Conqueror the capital of the Sen kings of Bengal was transferred thither from Gaur. In 1203 Lakshman Sen, the last of the dynasty, was over- thrown by the Muhammadan freebooter Muhammad-i-Bakhtyar KhiljT, who took the capital by surprise and subsequently conquered the greater part of Bengal proper. No reliable information is on record about the District until 1582, when the greater part of it was included at Todar Mai's settlement in sarkdr Satgaon, so called from the old trade emporium of that name near the modern town of Hooghly. At that time it was thinly inhabited, but its pandits were conspicuous for their learning. The present Maharaja of Nadia is a Brahman and has no connexion with Lakshman Sen's dynasty \ his family, however, claims to be of great antiquity, tracing its descent in a direct line from Bhattanarayan, the chief of the five Brahmans who were imported from Kanauj, in the ninth century, by Adisur, king of Bengal. At the end of the sixteenth century a Raja of this family assisted the Mughal general, Man Singh, in his expedition against Pratapaditya, the rebellious Raja of Jessore, and subsequently obtained a grant of fourteen parganas from Jahangir as a reward for his services. The family appears to have reached the zenith of its power and influence in the middle of the eighteenth century, when Maharaja Krishna Chandra took the side of the English in the Plassey campaign, and received from Clive the title of Rajendra Bahadur and a present of 12 guns used at Plassey, some of which are still to be seen in the Maharaja's palace.

Nadia District was the principal scene of the indigo riots of i860, which occasioned so much excitement throughout Bengal proper. The native landowners had always been jealous of the influence of the European planters, but the real cause of the outbreak was the fact that the cultivators realized that at the prices then ruling it would pay them better to grow oilseeds and cereals than indigo. Their discontent was fanned by interested agitators, and at last they refused to grow indigo. The endeavours made by the planters to compel them to do so led to serious rioting, which was not suppressed until the troops were called out. A commission was appointed to inquire into the relations between the planters and the cultivators, and matters gradually settled down ; but a fatal blow had been dealt to indigo cultivation in the District, from which it never altogether recovered. Several factories survived the agitation, and some still continue to work ; but the competition of synthetic indigo has reduced the j)rice of the natural dye to such an extent that the proprietors are finding it more profitable to give up indigo and to manage their estates as ordinary zaminddris.

Population

The population of the present area increased from 1,500,397 in 1872 to 1,662,795 in 1 88 1. Since that date it has been almost stationary, having fallen to 1,644,108 in 1801, and risen again to 1,667,491 m 1901. From 1857 to 1864 the District was scourged by the ' Nadia fever,' which caused a fearful mortality, especially in the old jungle-surrounded and tank-infested villages of the Ranaghat subdivision. There are no statistics to show the actual loss of life, but it is known that in some parts whole villages were depopulated. There was a recrudescence of the disease in 18S1-6, which caused the loss of population recorded at the Census of 1S91. Nadia is still one of the most unhealthy parts of Bengal, and in 1902 the deaths ascribed to fevers amounted to no less than 41 per 1,000 of the population. In 1881 a special commission ascribed the repeated outbreaks of malaria to the silting up of the rivers, which had become ' chains of stagnant pools and hotbeds of pestilence in the dry season.' Fevers accounted for no less than 82 per cent, of the deaths in 1901, as compared with the Provincial average of 70 per cent. Cholera comes next, and is responsible for 4 per cent, of the mortality.

The principal statistics of the Census of 1901 are shown below: —

The principal towns are Krishnagar, the head-quarters, Santipur, Nabadwip or Nadia, Kushtia, Ranaghat, and Meherpur. The Kushtia subdivision is by far the most populous portion of the District. The low density elsewhere is due to the silting up of the rivers, which has obstructed the drainage and caused long-continued unhealthiness. The soil also has lost much of its fertility, now that it is no longer enriched by annual deposits of silt. The material condition of the District is less satisfactory than that of its neighbours, and since 1891 it has lost 65,000 persons by migration, chiefly to the adjoining Districts and to Calcutta. Owing to this cause, it contains 1,015 females to every 1,000 males. The prevalent language is Bengali, which is spoken with remarkable purity by the educated classes. Muhammadans number 982,987, or 59 per cent, of the population, and Hindus 676,391, or 40-6 per cent. ; the preponderance of the former is most marked in the eastern part of the District, and espe- cially in the Kushtia subdivision. It is a curious circumstance that whereas Muhammadans form the majority of the whole population, they are in a very considerable minority in the towns, where they only form 26-3 per cent, of the total. Of the Muhammadans, large numbers belong to the puritanic sect of Farazis or Wahabis ; and the fanatic leader, Titu Mian, an account of whose rebellion in 1831 will be found in the article on the Twenty-four Parganas, recruited many of his followers in Nadia.

The Kaibarttas (111,000), the great race caste of Midnapore, are by far the most numerous caste in the District, and they are fol- lowed by the Goalas (cowherds), who number 71,000. The Brah- mans (47,000) are to a great extent the descendants of settlers in the time of the Sen kings. Next in numerical importance come the low-caste Bagdis, Muchis, and Chandals. Kayasths number 31,000, and there are 26,000 Malos or boatmen. Of every 100 persons in the District, 56 are engaged in agriculture, 16 in industry, one in commerce, 2 in one or other of the professions, and 17 in general labour. This District was the birthplace, in 1485, of the great re- ligious reformer Chaitanya, who founded the modern Vaishnava sect of Bengal. He was opposed to caste distinctions, and inveighed against animal sacrifices and the use of animal food and stimulants, and taught that the true road to salvation lay in bhakti or devotion to God. A favourite form of worship with this sect is the sankJrtan, or hymn-singing procession, which has gained greatly in popularity of late years. The town of Santipur, in the Ranaghat subdivision, is held sacred as the residence of the descendants of Adwaita, one of the two first disciples of Chaitanya. Most of his followers, while accepting his religious views, maintain their original caste distinctions, but a small minority abandoned them and agreed to admit to their community recruits from all castes and religions. These persons are known as Baishnabs or Bairagis. At the present day most of their new adherents join them because they have been turned out of their own castes, or on account of love intrigues or other sordid motives ; and they hold a very low position in popular estimation. A large proportion of the men live by begging, and many of the women by prostitution.

Among the latter-day offshoots of Chaitanya's teaching, one of the most interesting is the sect of Kartabhajas, the worshippers of the Karta or ' headman.' The founder of the sect was a Sadgop by caste, named Ram Saram Pal, generally known as Karta Baba, who was born about two centuries ago near Chakdaha in this District, and died at Ghoshpara. This sect accepts recruits from all castes and religions, and its votaries assemble periodically at Ghoshpara to pay homage to their spiritual head.

Christians number 8,091, of whom 7,912 are natives. The Church of England possesses 5,836 adherents, and the Roman Catholic Church 2,172. The Church Missionary Society commenced work in 1831, and has 13 centres presided over by native clergy or cate- chists, and superintended by 6 or 7 Europeans. The Roman Catholic Mission was established in 1855, and Krishnagar is now the head" quarters of the didcese of Central Bengal. In 1877 there was a schism among the adherents of the Church Missionary vSociety, and a number of them went over to the Church of Rome. The Church of England Zanana Mission works at Krishnagar and at Ratanpur, and a Medical mission at Ranaghat.

Agriculture

We have already seen that Nadia is not a fertile District. In most parts the soil is sandy, and will not retain the water necessary for the cultivation of winter rice, which is grown only . . , in the Kalantar and parts of the Kushtia subdivi- sion, occupying but one-ninth of the gross cropped area. The land has often to be left fallow to enable it to recover some degree of fertility. A very large number of the cultivators are mere tenants- at-will and have little inducement to improve their lands, and the repeated outbreaks of malaria have deprived them of vitality and energy. The dead level of the surface affords little opportunity for irrigation, which is rarely attempted. The total area under cultiva- tion in 1903-4. was 901 square miles, the land classed as cultivable waste amounting to 544 square miles. Separate statistics for the subdivisions are not available.

The staple crop is rice, grown on 775 square miles, or 86 per cent, of the net cropped area. The autumn crop is the most im- portant ; it occupies about 607 square miles and is usually reaped in August and September, but there is a late variety which is har- vested about two months later. The winter crop is reaped in December, and the spring rice in March or April. The winter and spring crops are transplanted, but the autumn rice is generally sown broadcast. After rice, the most important crops are gram and other pulses, linseed, rape and mustard, jute, wheat, indigo, and sugar-cane. The cultivation of indigo is contracting, and only 6,300 acres were sown in 1903-4. After the autumn rice is harvested, cold-season crops of pulses, oilseeds, and wheat are grown on the same fields, and 79 per cent, of the cultivated area grows two crops. The rice grown in the District is insufficient to satisfy the local demand. In some parts, especially in the subdivision of Chuadanga, the cultivation of chillies [Capsici/fii frutescens) and turmeric forms an important feature in the rural industry, upon which the peasant relies to pay his rent.

Cultivation is extending, but no improvement has taken place in agricultural methods. The manuring practised is insufficient to restore to the soil what the crops take from it, and it is steadily deteriorating. Very little advantage has been taken of the Land Improvement *and Agriculturists' Loans Acts.

Trade and communications

The local cattle are very inferior ; the pasturage is bad, and no care is taken to improve the breeds by selection or otherwise. Santipur was once famous for its weavers, and in the beginning of the nineteenth century the agent of the East India Company used to purchase musHns to the annual value of £150,000. The industry, however, has almost died out. Very little Trade and muslin is now exported, and even the weaving of ordmary cotton cloth is on the decline. Sugar-renning by European methods has proved unsuccessful, but there are several date-sugar refineries in native hands at Santipur, Munshiganj, and Alamdanga. Brass-ware is manufactured, particularly at NabadwTp and Meherpur, and clay figures are moulded at Krishnagar ; the latter find a ready sale outside the District and have met with recognition at exhibitions abroad. There is a factory at Kushtia under European management for the manufacture of sugar-cane mills. Owing to its numerous waterways, the District is very favourably situated for trade. Moreover, the Eastern Bengal State Railway runs through it for a distance of nearly 100 miles. Gram, pulses, jute, linseed, and chillies are exported to Calcutta, and sugar to Eastern Bengal. Coal is imported from Burdwan and Manbhum ; salt, oil, and piece-goods from Calcutta ; and rice and paddy from Burdwan, Dinajpur, Bogra, and Jessore.

The chief railway trade centres are Chuadanga, Bagula, Ranaghat, Damukdia, and Poradaha ; and those for river traffic are Nabadwip on the Bhagirathi, Santipur and Chakdaha on the Hooghly, Karimpur, Andulia, Krishnagar, and Swarupganj on the JalangI, Hanskhali on the ChurnT, Boalia and Krishnaganj on the Matabhanga, Nonaganj on the IchamatT, Alamdanga on the Pangasi, and Kushtia, Kumarkhali, and Khoksa on the Garai. About thirty-eight fairs are held yearly. Most of them, however, are religious gatherings ; the best attended are the fairs held at Nabadwip in February and November, at Santipur in November, at Kulia in January, and at Ghoshpara in March.

The Eastern Bengal State Railway (broad gauge) passes through the District from Kanchrapara on the southern, to Damukdia on the northern boundary ; and a branch runs east from Poradaha, through Kushtia, to (loalundo in Faridpur District. The central section of the same railway runs from Ranaghat eastwards to Jessore, and a light railway (2 feet 6 inches gauge) from Ranaghat to Krishnagar via Santipur. A new line has recently been constructed from Ranaghat to Murshidabad.

The District board maintains 803 miles of roads, in addition to 526 miles of village tracks. Of the roads, 107 miles are metalled, including the roads from Krishnagar to Bagula and Ranaghat, from Meherpur to Chuadanga, and several others which serve as feeders to the railway. Of the unmetalled roads the most important is the road from Barasat in the Twenty-four Parganas, through Ranaghat and Krishnagar, to Plassey in the north-west corner of the District. All the rivers are navigable during the rainy season by boats of large burden, but in the dry season they dwindle to shallow streams and are obstructed by sandbanks and bars. Before the era of rail- ways the Nadia Rivers afforded the regular means of communica- tion between the upper valley of the Ganges and the sea-board, and elaborate measures are still adopted to keep their channels open. Steamers ply daily between Calcutta and Kalna via Santipur, and on alternate days, during the rains, between Kalna and Murshidabad via Nabadwip. Numerous steamers pass up and down the Padma, and a steam ferry crosses that river from Kushtia to Pabna.

Famine

Nadia suffered severely in the great famine of 1770. The worst famines of recent times were those of 1866 and 1896. On the former occasion relief from Government and private funds was necessary from April to October; 601,000 per- sons were gratuitously relieved, and 337,000 were employed on relief works. The famine of 1896 affected about two-fifths of the District including the Kalantar, the Meherpur subdivision, and the western portions of the Kushtia and Chuadanga subdivisions. The grant of relief continued from November, 1896, until September, 1897, the total expenditure from public funds being 6^ lakhs. The daily average number of persons employed on relief works was 8,913. In July, 1897, the average rose to 25,500 persons, and gratuitous relief was afforded daily to an average of 33,000 persons.

Administration

For administrative purposes Nadia is divided into five subdivisions, with head-quarters at Krishnagar, Kushtia, Ranaghat, Meherpur, and Chuadanga. The District Magistrate is assisted , . . at head-quarters by a staff of five Deputy-Magistrate- Collectors, one of whom is solely employed on land acquisition work. The Meherpur subdivision is in charge of an Assistant Magistrate- Collector, while the other subdivisional officers are Deputy-Magistrate- Collectors.

For the disposal of civil work, the judicial staff subordinate to the District and Sessions Judge consists of a Sub-Judge and two Munsifs at Krishnagar, two Munsifs at Kushtia, and one each at Meherpur, Chuadanga, and Ranaghat. The criminal courts are those of the District and Sessions Judge, the District Magistrate, four Deputy- Magistrates at Krishnagar, and the subdivisional officers in the other subdivisions. No class of crime is now specially prevalent, but at the beginning of the nineteenth century the District was notorious for dacoity and rioting.

The current land revenue demand for 1903-4 was 9-1 lakhs, due from 2,492 estates. Of these, 2,216 with a revenue of 8-14 lakhs are per- manently settled, 246 estates paying Rs. 73,000 are temporarily settled, and 30 estates paying Rs. 22,000 are managed direct by the Collector. In addition, there are 299 revenue-free estates and 9,169 rent-free lands, which pay road and public works cesses. The gross rental of the District has been returned by the proprietors and tenure-holders at 34 lakhs, and of this sum the Government revenue demand represents 26-7 per cent. The incidence of the land revenue is R. 0-15-3 P^r acre on the cultivated area.

The utbandi tenure is not peculiar to Nadia, but is especially common in this District, where about 65 per cent, of the cultivated land is held, under it. The tenant pays rent only for the land he cultivates each year ; and he cannot acquire occupancy rights unless he tills the same land for twelve years consecutively, which in fact he rarely does. Mean- while the landlord can raise the rent at his pleasure, and if the tenant refuses to pay, he can be ejected. This tenure deprives the tenant of any incentive to improve his lands, and at the same time encourages rack-renting. It appears, however, to be gradually giving way to the ordinary system. Where the tenants have occupancy rights, the rent of rice land ranges from' Rs. 1-4 to Rs. 4-8 an acre; garden land is rented at about Rs. 11 an acre, and land under special crops, such as chillies and sugar-cane, at Rs. 7-8 or even more. Lands leased under the utbandi system pay higher rents, as much as Rs. 12 to Rs. 23 being paid per acre, as compared with R. i to Rs. 2-9 for similar lands held on long leases.

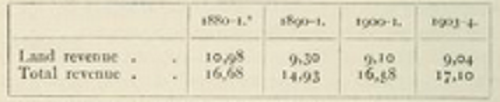

The following table shows the collections of land revenue and of total revenue (principal heads only), in thousands of rupees : —

- In 1880-1 the District included the subdivision of Bangaon, wliich was

subsequently transferred to Jessorc.

Outside the nine towns which enjoy municipal governmeni, local affairs are managed by a District board with five subdivisional local boards. The income of the District board in 1903-4 was Rs. 1,89,000, of which Rs. 90,000 was derived from rates ; and the expenditure was Rs. 1,42,000, including Rs. 74,000 spent on public works and Rs. 42,000 on education.

The District contains 21 police stations and 13 outposts. In 1903 the force at the disposal of the District Superintendent consisted of 5 inspectors, 48 sub-inspectors, 47 head constables, and 627 constables, maintained at a cost of Rs. 1,38,000. There is one policeman to every 5-4 square miles and to 3,231 persons, a much larger proportion than the Provincial average. Besides, there are 3,990 village chmikiddrs under 347 daffaddrs.

The District jail at Krishnagar has accommodation for 216 prisoners. and subsidiary jails at each of the other subdivisional head-quarters for a total of 61. Nadia District, in spite of its proximity to Calcutta, is not especially remarkable for the diffusion of the rudiments of learning. In 1901 the proportion of literate persons was 5-6 per cent. (10-4 males and 0-9 females). The total number of pupils under instruction increased from about 20,000 in 1883 to 29,364 in 1892-3 and 31,102 in 1900-1, while 31,573 boys and 3,442 girls were at school in 1903-4, being respectively 25-4 and 2-7 per cent, of the number of school-going age. The number of educational institutions, public and private, in 1903-4 was 1,026, including an Arts college, '90 secondary, 887 primary, and 48 special schools. The expenditure on education was 3-26 lakhs, of which Rs. 62,000 was met from Provincial funds, Rs. 40,000 from District funds, Rs. 3,000 from municipal funds, and 1-37 lakhs from fees. Nadia has always been famous as a home of Sanskrit learning, and its tols, or indigenous Sanskrit schools, deserve special mention. In these Sviriti (Hindu social and religious law) and Nydya (logic) are taught, many of the pupils being attracted from considerable distances by the fame of these ancient institutions. A valuable report on these tols, by the late Professor E. B. Cowell (Calcutta, 1867), contains a full account of the schools, the manner of life of the pupils, and the works studied. Most of the toh are in the town of Nabadwip, but there are a few also in the surrounding villages.

In 1903 the District contained 13 dispensaries, of which 7 had accommodation for 52 in-patients. The cases of 66,000 out-patients and 646 in-patients were treated during the year, and 2,700 opera- tions were performed. The expenditure was Rs. 21,000, of which Rs. 5,000 was met by Government contributions, Rs. 3,000 from Local and Rs. io,ooo from municipal funds, and Rs. 1,935 ^O'^ subscriptions. In addition, the Zanana Mission maintains a hospital and three dis- pensaries, and large numbers of patients are treated by the doctors of the Ranaghat Medical Mission.

Vaccination is compulsory only within municipal areas. In 1903-4 the number of persons successfully vaccinated was 50,000, or 33 per 1,000 of the whole population. [Sir W. W. Hunter's Statistical Account of Bengal, vol. ii (1875) ; Fever Commission's i?^/(?/-/ (Calcutta, 1881).]

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.