Naga Hills

Contents |

Naga Hills, 1908

Physical aspects

A District in Eastern Bengal and Assam, lying between 24° 42' and 26° 48' N. and 93° 7' and 94° 50 'E., with an area of 3,070 square miles. It is bounded on the north by Nowgong and Sibsagar ; on the west by the North Cachar hills ; on the south by the State of Manipur; and on the east by a line which follows for the most part the course of the Dikho and Tizu rivers, beyond which lie hills inhabited by independent tribes. The District consists of a long narrow strip of hilly country. The Barail range enters it from the west, and the Japvo peak a little to the south of Physical Kohlma attains a height of nearly 10,000 feet. Here

it is met by the meridional axis of elevation pro- longed from the Arakan Yoma, and from this point the main range runs in a north-north-easterly direction. The general effect is that of a gigantic L in the reverse position, the junction of the two arms forming an obtuse instead of a right angle, with minor ridges branching off on either side towards the east and west. The hills generally take the form of serrated ridges, clothed for the most part with dense forest and scrub and grass jungle, and separated from one another by deep valleys, through which a stream or river makes its way to the plains. The largest river in the District is the Doiang, but it is only navigable for a few miles within the hills. The channel is blocked by rocks at Nabha; or boats could proceed as far as the Mokokchung-Wokha road. The DiKHO is also navigable for a short distance within the hills. though the head-hunting proclivities of the tribes inhabiting the right bank might render the voyage dangerous ; but the same cannot be said of the Jhanzi and Disai, which flow through the plains of Sibsagar into the Brahmaputra. East of the watershed is the Tizu with its tributary the Lanier, which falls into the Chindwin.

The hills have never been properly explored, but they are believed to be composed of Pre-Tertiary rocks, overlaid by strata of the Tertiary age. The flora of the Naga Hills resembles that of Sikkim up to the same altitude. In their natural state, the hills are covered with dense ever- green forest ; and where this forest has been cleared for cultivation, high grass reeds and scrub jungle spring up in great profusion. The usual wild animals common to Assam are found, the list includ- ing elephants, bison {Bos gai/n/s), tigers, leopards, bears, serow, sambar, and barking-deer, and the flying lemur {Nydicelus tardigrade s). A horned pheasant [Tragopati blythi) has also been shot in the hills.

The climate generally is cool, and at Kohima the thermometer seldom rises above 80°. The higher hills are healthy, but during the rains the valleys and the lower ranges are decidedly malarious. The rainfall, as in the rest of Assam, is fairly heavy. At Kohima it is 76 inches in the year, but farther north, at Wokha and Tamlu, it exceeds 100 inches. The earthquake of June 12, 1897, was dis- tinctly felt, but not much damage was done, and there is no record of any serious convulsion of nature having ever occurred in the District.

History

Of the early history of the Nagas, as of other savage tribes, very litde is known. It is interesting, however, to note that Tavernier in the latter half of the seventeenth century refers to people in Assam, evidently Nagas, who wore pigs' tusks on their caps, and very few clothes, and had great holes for ear-rings through the lobes of their ears, fashions that survive to the present day. In the time of the Ahom Rajas they occasionally raided the plains, but the more powerful princes succeeded in keeping them in check, and even compelled them to serve in their military expeditions. The first Europeans to enter the hills were Captains Jenkins and Pemberton, who marched across them in 1832. The story of the early British relations with these tribes is one of perpetual conflict. Between 1839 and 1 85 1 ten military expeditions were led into the hills, the majority of which were dispatched to punish raids. After the last of these, in which the village of Kekrima, which had challenged the British troops to a hand-to-hand fight, lost 100 men, the Government of India decided upon a complete withdrawal, and an abstention from all inter- ference with the hillmen. The troops were recalled in March, 1851 ; and before the end of that year 22 Naga raids had taken place, in which 55 persons were killed, lo wounded, and 113 taken captive. The policy of non-interference was still adhered to, but the results were far from satisfactory; and between 1853 and 1865, 19 raids were com- mitted, in which 233 British subjects were killed, wounded, or captured. The Government accordingly agreed to the formation of a new Dis- trict in 1866, with head-quarters at Samaguting. Captain Butler, who was appointed to this charge in 1869, did much to consolidate British power in the hills, and exploration and survey work were diligently pushed forward. These advances were, however, resented by the tribesmen ; and in February, 1875, Lieutenant Holcombe, who was in charge of one of the survey parties, was killed, with 80 of his followers. Butler himself was three times attacked, and was mortally wounded the following ("hristmas Day by the i.hota Nagas of Pangti. Two years later his successor, Mr. Carnegy was accidentally shot by a sentry, when occupying the village of Mozenia, which had refused to give up the persons guilty of a raid into North Cachar. In 1878 it was decided to transfer the head-quarters of the District to Kohima, in the heart of the Angami country. During the rains of 1879 indications of trouble began to present themselves ; and before starting on his cold-season tour the Political Officer, Mr. Damant, determined to visit the powerful villages of Jotsoma, Khonoma, and Mozema. On reaching Khonoma, he found the gate of the village closed, and as he stood before it, he was shot dead. The Nagas then poured a volley into his escort, who turned and fled with a loss of 35 killed and 19 wounded. The whole country-side then rose and proceeded to besiege the stockade at Kohima, and the garrison were reduced to great straits before they were relieved by a force from Manipur. A campaign against the Nagas ensued, which lasted till March, 1880. The most notable event in this campaign was a daring raid made by a party of Khonoma men, at the very time when their village was in the occupation of British troops, upon the Baladhan garden in Cachar, where they killed the manager and sixteen coolies and burnt down everything in the place, U'ithin the short space of five years four European officers while en- gaged in civil duties had come to a violent end ; but the Nagas had begun to learn their lesson, and under the able administration of Mr. McCabe the District was reduced to a condition of peace and order. In 1875 a subdivision was opened at Wokha to exercise con- trol over the Lhota Nagas, who on several occasions had attacked survey parties sent into the hills. Fourteen years later it was found possible to withdraw the P^uropean officer stationed there, and a sub- division was opened at Mokokchung in the Ao country. In 1898 the Miklr and Rengma Hills, with the valley of the Dhansiri, which formed the most northerly part of the District as originally constituted, were transferred to Nowgong and Sibsagar, as, on the completion of the Assam-Bengal Railway, it was found more convenient to administer this tract of country from the plains than from Kohlma. Lastly, in 1904, the tract formerly known as the 'area of political control' was formally incorporated in the District, and the boundary was pushed forward to the Tizu river, and even across it on the south so as to include four small AngamI villages on the farther bank.

Population

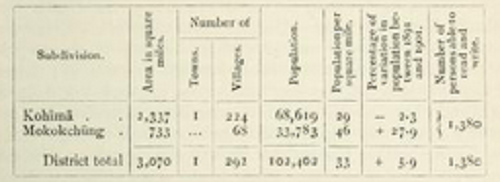

A census of the hills was first taken in 1891, when the i)opu- lation was 96,637 ; in 1901 the number had risen to 102,402. The tract recently incorporated within the District contains about 30,000 persons. There are two sub- divisions, KohIma and Mokokchijng, with head-quarters at places of the same names; and in 1901 the District contained one town, KohLma (population, 3,093), and 292 villages. The following table gives for each subdivision particulars of area, population, &c. The large increase which occurred in Mokokchung between 1891 and 1901 is due to immigration and to the addition of new territory.

Nearly 96 per cent, of the population in 1901 were still faithful to their various forms of tribal religion. The American Baptist Mission has branches at Kohima and at Impur in the MokokchCmg sub- division, and practically the whole of the native Christians (579) were members of this sect. The Nagas do not at present seem to be attracted to either Hinduism or Christianity. Both of these religions would, in fact, impose restraints upon their ordinary life, and would debar them from many pleasures, such as the consumption of beef and liquor, and a certain latitude in their sexual relations to which they have grown accustomed.

The various languages of the Naga group, though classified under one generic head, differ very widely from one another, and in some cases the language spoken in one village would not be understood by people living only a short distance away. Angami, ChunglT, and Lhota are in most general use. The principal tribes are the Angamis (27,500), the Aos (26,800), the Lhotas (19,300), and the Semas, who form the greater part of the population in the newly added territory.

The term Naga is applied by the Assamese to a number of difiereni tribes, the majority having as yet made little progress on the [t.uh (^{ civilization, who occupy the hills between the Brahmaputra valley and Burma on the north and south, the Jaintia Hills on the west, and the country inhabited by the Khamtis and Singphos on the east. The Nagas, like the rest of the tribes of Assam, belong to the great Tibeto- Burman famil)-, but they are differentiated from most of the other sections of the horde by their warlike and independent spirit and by their indifference to the sanctity of human life. Among the Nagas, society is seen resolved into almost its ultimate unit ; and, though they arc divided into several different tribes, it must not be supposed that the tribe is the basis upon which their society has been organized. The most warlike and important tribe are the Angamis, who occupy the country round Kohlma. North of them come the Rengmas, then the Lhotas, while north and east of the Lhotas are the Aos, whose villages stretch up to the Dikho river. On the farther side of this river are a number of tribes with which we are at present but imperfectly acquainted, but the Semas live east of the Rengmas and the Aos.

The Nagas, as a whole, are short and sturdy, with features of a markedly Mongolian type. The Lhotas are exceptionally ugly, and among all the tribes the average of female beauty is extremely low. The people, as a rule, are cheerful and friendly in times of peace, and are musically inclined. As they march along the roads they keep time to a chant, which is varied to suit the gradient and the length of step ; and they sing as they reap their rice, their sickles all coming forward in time to the music. East of tlie Dikho there are chiefs who enjoy certain privileges and exercise authority over their villages, and chiefs are also found among the Sema tribe. These chiefs hold their position by right of inheritance, and, as among the Lushais, the sons, as they grow up, mo\e away and found separate villages. The ordinary Naga village is, however, a very democratic coumiunity, and the leaders of tlie people exercise comparatively little influence. They are noted for their skill in war or in diplomacy, or for their wealth ; but their orders are obeyed only so far as they are in accord with the inclinations of the community at large, and even then the wishes of the majority are not considered binding on the weaker party. Among the Angamis, in fact, the social unit is not the village, but the k/iel (a term borrowed from the Afghan border), an exogamous subdivision of which there are several in each village. There is great rivalry between the k/ze/s, which, prior to British occupation, led to bitter blood-feuds. The following extract from the report of the Political Officer in 1876 shows the utter want of unity in an AngamI Naga village : —

In the middle of July a party of forty men from Mozema went over to KohTma and were admitted by one of the Me/s friendly to them, living next to the Puchatsuma cjuartcr, into which they passed and killed all they could find, viz. one man and twenty-five women and children. The people of the other kJiels made no effort to mterfere, but .stood looking on. One of the onlookers told me that he had never seen such fine sport as the killing of the children, for it was just like killing fowls.'

This extraordinary separation oikhelixova khelii the more remarkable, in that they must all be intimately connected by marriage, as a man is compelled to take his wife from some khel other than his own.

The villages are, as a rule, built on the tops of hills, and, except among the Semas, are of considerable size, Kohlma containing about 800 houses. They are strongly fortified and well guarded against attack. The houses are built closely together, in spite of the frequency of destructive fires. The posts and rafters are of solid beams, and the roof at the sides reaches nearly to the ground. Those of the Lhotas and Aos are laid out in regular streets, but there is a complete lack of symmetry in the Angami and Sema villages.

Among the naked Nagas the men are often completely destitute of clothing, and it is said that the women when working in the fields sometimes lay aside the narrow strip of cloth which is their solitary garment. At the opposite end of the scale come the Angamis, whose dress is effective and picturesque. Their spears and daos are orna- mented with red goats' hair, and they wear gaiters and helmets of dyed cane, and brightly coloured sporrans. The Aos, too, have a nice taste in dress. But the Lhotas are an untidy dirty tribe ; and the working dress for a man consists of a small cloth passed between the legs and fastened round the waist, which barely serves the purpose for which it is intended, while a woman contents herself with a cloth, about the size of an ordinary hand towel, round her waist. Both sexes are fond of ornaments, and used pigs' tusks, sections of an elephant's tusk, agates, carnelians, necklaces of beads, shells, and brass ear-rings. The weapons used by all the tribes are spears, shields, and daos, or billhooks. Their staple food is rice, but few things come amiss to a Naga, and they eat pigs, bison, dogs, giti (big lizards), and pythons, and any kind of game, however putrid. Like other hill tribes, they are great drinkers of fermented beer.

Oaths are generally confirmed b\ invoking the wrath of Heaven on the swearer if he tells a lie. An AngamT who has sworn by the lives of his khel will never tell a lie. He bares one shoulder, and places his foot in a noose in which a piece of cow-dung has been placed before taking the oath. The most careful supervision is, however, necessary to ensure that the correct formula is employed, as by some verbal quibble he may exempt himself from all liability. The van- quished, too, occasionally eat dirt in a literal sense as testimony to the sincerity of their vows.

Adult marriage only is in vogue, and prior to the performance of that ceremony the girls are allowed great latitude. Those of the Aos sleep in separate houses two or three together, and are visited nightly by their lovers. These lovers are, as a rule, members of the girl's own khel, whom she is debarred by custom from marrying ; and, as illegitimate children are rare, it is to be presumed that abortion and infanticide are not unknown. The former practice is in vogue among the Aos, while of the AnganiTs^ it was said to have been the rule for the girl to retire alone into the jungle when she felt her time approach- ing, and strangle the baby, when it was born, with her own hands. The other tribes are not quite so frankly promiscuous as the Aos, but a Naga bride who is entitled to wear the orange blossom of virginity on the occasion of her marriage is said to be extremely rare. The following is a description of the marriage ceremony of the Angamis : The young man, having fixed his choice upon a certain girl, tells his father, who sends a friend to ascertain the wishes of her parents. If they express conditional approval, the bridegroom's father puts the matter further to the test by strangling a fowl and watching the way in which it crosses its legs when dying. If the legs are placed in an inauspicious attitude, the match is immediately broken off; but if this catastrophe is averted, the girl is informed of the favourable progress of the negotiations. At this stage, she can exercise a power of veto, as, if she dreams an inauspicious dream within the next three days, her suitor must seek a bride elsewhere ; but if all goes favourably, the wedding day is fixed. Proceedings open with a feast at the bride's house, and in the evening she proceeds to her husband's home ; but, though she sleeps there, he modestly retires to the bachelors' club. The next day brings more feasting, but night separates the young couple as before. On the third day they visit their fields together, but not till eight or nine days have elapsed is the village priest called in, and the happy pair allowed to consummate their wishes. The Angamis and the Aos do not, as a rule, pay money for their wives, but among the Lhotas and the Semas the father of the girl generally receives from 80 to 100 rupees. Divorces are not uncommon, especially in the case of the Angamis, who do not take more than one wife at a time. idows are allowed to remarry, but those of the AngamI tribe are expected to refrain from doing so if they have children.

The dead are, as a rule, buried in shallow graves in close vicinity to their homes. The funeral is an occasion for much eating and drinking, and among the Angamis the whole of a' man's propert)' is sometimes dissipated on his funeral baked meats. The friends of the deceased lament vociferously round the grave till the coffin has been lowered. The conclusion of the ceremony is thus described by the late Mr. McCabe, the officer who had most to do with the pacification of the hills : --

' At this stage of the proceedings, the friends of the deceased suddenly stopped sobbing, dried their eyes, and marched off in a most businesshke manner. A civiHzed Naga, who had been as demonstrative with his umbrella as his warrior friends had been with their spears, solemnly closed it and retired. A large basketful of dhdn (rice), millet, ddl (pulse), and Job's-tears was now thrown into the grave, and over tliis the earth was rapidly filled in.'

The Aos, however, do not bury their dead, but place them in bamboo coffins and smoke them for a few weeks in the outer room of the house. The corpse is then remoAed to the village cemetery, and placed on a bamboo platform. This cemetery invariably occupies one side of the main road leading to the village gate.

During the father's lifetime his sons receive shares of his landed property as they marry, with the result that the youngest son usually inherits his father's house. The religion of the Nagas does not differ materially from that of the other hill tribes in Assam. They have a vague belief in a future life, and attribute their misfortunes to the machinations of demons, whom they propitiate with offerings.

The custom which has attracted most attention, and which differen- tiates the Nagas from other Tibeto-Burman tribes, such as the Bodos, Mlklrs, Daflas, and sub- Himalayan people, is their strange craving for human heads. Any head was valued, whether of man, woman, or child ; and victims were usually murdered, not in fair fight, but by treachery. Sometimes expeditions on a large scale were undertaken, and several villages combined to make a raid. Even then they would usually retire if they saw reason to anticipate resistance. Most Angamis over fifty have more than one head to their credit, and the chief interpreter in the Kohima court is said to have taken eighteen in his unregenerate days. Head-hunting is still vigorously prosecuted by Nagas living beyond the frontier, and human sacrifices are offered to ensure a good rice harvest. A curious custom is the genna, which may affect the village, the khel, or a single house. Persons under a genfza remain at home and do no work ; nothing can be taken into or brought out of their village, and strangers cannot be admitted. Among other quaint beliefs, the Nagas think that certain men possess the power of turning themselves into tigers, while the legend of the Amazons is represented by a village in the north-east, peopled entirely by women, who are visited by traders from the surrounding tribes, and thus enabled to keep up their numbers.

Agriculture

The ordinary system of cultivation is tliat known as Jhu/n. The jungle growing on the hill-side is cut down, and the undergrowth is burned, the larger trees being left to rot where . . lliey lie. I he ground is then lightly hoed over, and seeds of rice, maize, niilkt. Jobs-tears (Coiix Lacryma), ( clullics. and various kinds of vegetables dibbled in. The same plot of land is cropped only for two years in succession, and is then allowed to lie fallow for eight or nine years. Further cropping would be liable to destroy the roots of ikra and bamboo, whose ashes serve as manure when the land is next cleared for cultivation, while after the second harvest weeds spring up with such rapidity as to be a serious impediment to cultivation. Cotton is grown, more especially on the northern ridges inhabited by the Lhotas and Aos, who bring down considerable quantities for sale to the Marwaris of Golaghat. A more scientific form of cultivation is found among the Angami Nagas, whose villages are surrounded by admirably constructed terraced rice- fields, built up with stone retaining-walls at different levels, and irrigated by means of skilfully constructed channels, which distribute the water over each step in the series. This S3'stem of cultivation is believed to have extended northwards from Manipur, and to have been adopted by the Angamis, partly from their desire for better kinds of grain than Job's-tears and millet, as jhum rice does not thrive well at elevations much exceeding 4,000 feet, and partly from a scarcity of jhum land. It has the further advantage of enabling the villagers to grow their crops in the immediate neighbourhood of their homes, a consideration of much importance before the introduction of British rule compelled the tribes to live at peace with one another. Efforts are now being made to introduce this system of cultivation among the Aos and the Semas. 'I'he Nagas do not use the plough, and the agricultural implements usually employed are light hoes, daos, rakes, and sickles. No statistics are available to show the cultivated area, or the area under different crops. Little attempt has been made to intro- duce new staples. Potatoes when first tried did not flourish, but a subsequent experiment has been more successful. Cattle are used only for food, and are in consequence sturdier and fatter animals than those found in the plains of Assam. The domesticated mitha)i {Bos frontalis) is also eaten ; but the Nagas, like other hill tribes in Assam, do not milk their cows.

The whole of the hills must once have been covered with dense evergreen forest; but the jhum system of cultivation, which necessitates the periodical clearance of an area nearly five or six times as large as that under cultivation in any given year, is very unfavourable to tree growth. A ' reserved ' forest, covering an area of 63 square miles, has recently been constituted in the north-east corner of the District. Elsewhere, the tribes are allowed to use or destroy the forest produce as they please. In the higher ridges oaks and pines are found, while lower down the most valuable trees are gomari {Gmelima arhorca), poma {Cedrela Toona), sam {Arfocarpus C/iap/as/ui), and uriam {Lis- chojia javanica). The District has never been properly explored, but the hills over- looking the Sibsagar plain contain three coal-fields — the Xazira, the Jhanzi, and the Disai. The Nazira field is estimated to contain about 35,000,000 tons of coal, but little has been done to work it. The coal measures contain iron ore in the shape of clay ironstone and impure limonite, and petroleum is found in the Nazira and Disai fields.

Trade and communications

The manufacturing industries of the Naga Hills are confined to the production of the few rude articles required for domestic use. The most important is the weaving of coarse thick cloth of various patterns, the prevailing colours being dark blue — m some cases so dark as to be almost black — with red and yellow stripes, white, and brown. Many of these cloths are tastefully ornamented with goat's hair dyed red and cowries. Iron spear-heads, daos, hoes, and rough pottery are also made. The Angami Nagas display a good deal of taste in matters of dress, and a warrior in full uniform is an impressive sight ; but the majority of the tribes wear little clothing, and only enough is woven to satisfy the wants of the household.

Wholesale trade is entirely in the hands of the Marwari merchants known as Kayahs. The principal imports are salt, thread, kerosene oil, and iron ; and KohTma is the largest business centre. The Nagas trade in cotton, chillies, and boats, which they exchange for cattle and other commodities from the plains. The most important trading villages are Khonoma, Mozema, and Lozema, and the tribes who are keenest at a bargain are the Semas and Angamis. Members of the latter tribe sometimes go as far afield as Rangoon, Calcutta, and Bombay, but the Semas never venture beyond the boundaries of their own Province.

In 1903-4, 73 miles of cart-roads and 470 miles of bridle-paths were maintained in the District. The cart-road from Dimapur to Mani- pur runs across the hills, connecting Kohmia with the Assam-Bengal Railway. Generally speaking, the means of communication in the District are sufficient for the requirements of its inhabitants.

Administration

For administrative purposes, the District is divided into two sub- divisions, KohIma and Mokokchung. The Deputy-Commissioner is stationed at Kohima, and has one Assistant, who is usually a European. Mokokchung is m charge of a European police officer, and an engineer and a civil surgeon are posted to the District. The High Court at Calcutta has no jurisdiction in the District, except in criminal cases in which European British subjects are concerned ; the Codes of Criminal and Civil Procedure arc not in force, and the Deputy-Commissioner exercises powers of life and death, subject to confirmation by the Chief Commissioner. Many disputes, both of a civil and criminal nature, are decided in the village without reference to the courts. Theft is punished by the Nagas with the utmost severity. If a man takes a little grain from his neighbour's field, he forfeits not only his own crop, but the land on which it has been grown, while theft from a granary entails expulsion from the village and the confiscation of the offender's property. Generally speaking, the policy of Government is to interfere as little as possible with the customs of the people, and to discourage the growth of any taste for litigation. Considering the short time that has elapsed since the Nagas were redeemed from barbarous savagery, the amount of serious crime that takes place within the boundaries of the District is comparatively small.

Land revenue is not assessed, except on a small estate held by the American Baptist Mission. A tax at the rate of Rs. 3 per house is realized from the Angami Nagas. For other Nagas the rate is Rs. 2 and for foreigners Rs. 5.

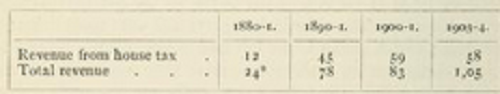

The table below shows the revenue from house tax and the total revenue, in thousands of rupees: —

- Exclusive of forest receipts.

The civil police consist of 29 head constables and men under a sub- inspector, but their sphere of action does not extend beyond Kohinia town and the Manipur cart-road. The force which is really responsible for the maintenance of order in the District is the military police battalion, which has a strength of 72 officers and 598 men. Prisoners are confined in a small jail at Kohima, which has accommodation for 32 persons.

Education has not made much progress in the hills since they first came under British rule. The number of pupils under instruction in 1890-1, 1900-1, and 1903-4 was 297, 319, and 647 respectively. At the Census of 1901 only 1-3 per cent, of the population (2-5 males and o-i females) were returned as literate. There were i secondary, 22 primary, and 2 special schools in the District in 1903-4, and 76 female scholars. More than two-thirds of the pupils at school were in primary classes. Of the male population of school-going age, 5 per cent, were in the primary stage of instruction. The total expenditure on education in 1903-4 was Rs. 6,000, of which Rs. 256 was derived from fees. About 32 per cent, of the direct expenditure was devoted to primary scliools.

'I'lie District possesses 3 hospitals, with accommodation for 24 in- patients. In 1904 the number of cases treated was 21,000, of wliom 500 were in-patients, and 200 operations were i)erformed. The expenditure was Rs. 5,000, the whole of which was met from Provincial revenues.

The advantages of vaccination are fully appreciated by the people, and, though in 1903-4 only 39 per 1,000 of the population were pro- tected, this was largely below the average for the five preceding years.

[B. C. Allen, District Gazetteer of the Ndgd Hills (1905). A monograph on the Naga tribes is under preparation.]

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.