Nat

This article was written in 1916 when conditions were different. Even in Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

From The Tribes And Castes Of The Central Provinces Of India

By R. V. Russell

Of The Indian Civil Service

Superintendent Of Ethnography, Central Provinces

Assisted By Rai Bahadur Hira Lal, Extra Assistant Commissioner

Macmillan And Co., Limited, London, 1916.

NOTE 1: The 'Central Provinces' have since been renamed Madhya Pradesh.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from the original book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot these footnotes gone astray might like to shift them to their correct place.

Contents |

Nat

Nat, Badi, Dangf-Charha, Karnati, Bazig-ar, Sapepa

Nat (Sanskrit Nata—a dancer) appears to be a proper ^ / 1 x caste. applied indefinitely to a number of groups of vagrant acrobats and showmen, especially those who make it their business to do feats on the tight-rope or with poles, and those who train and exhibit snakes. Badi and Bazigar mean a rope-walker, Dang-Charha a rope-climber, and Sapera a snake-charmer.

In the Central Provinces the Garudis or snake-charmers, and the Kolhatis, a class of gipsy acrobats akin to the Berias, are also known as Nat, and these are treated in separate articles. It is almost certain that a considerable section, if not the majority, of the Nats really belong to the Kanjar or Beria gipsy castes, who themselves may be sprung from the Doms.^ Sir D.

Ibbetson says : " They wander about with their families,

settling for a few days or weeks at a time in the vicinity

of large villages or towns, and constructing temporary

shelters of grass. In addition to practising acrobatic feats

and conjuring of a low class, they make articles of grass,

straw and reeds for sale ; and in the centre of the Punjab

are said to act as Mirasis, though this is perhaps doubtful.

They often practise surgery and physic in a small way and

• This article is partly compiled from notes furnished by Mr. Aduram

Chaudhri and Mr. Jagannath Prasad, Naib-TahsUdars. 2 g^g j^jj_ Kanjar.

are not free from suspicion of sorcery." ^ This account

would just as well apply to the Kanjar gipsies, and the

Nat women sometimes do tattooing like Kanjar or Beria

women. In Jubbulpore also the caste is known as Nat

Beria, indicating that the Nats there are probably derived

from the Beria caste. Similarly Sir H. Risley gives Bazigar

and Kabutari as groups of the Berias of Bengal, and states

that these are closely akin to the Nats and Kanjars of

Hindustan.- An old account of the Nats or Bazigars ^

would equally well apply to the Kanjars ; and in Mr.

Crooke's detailed article on the Nats several connecting

links are noticed.

The Nat women are sometimes known as Kabutari or pigeon, either because their acrobatic feats are like the flight of the tumbler pigeon, or on account of the flirting manner with which they attract their male customers.'* In the Central Provinces the women of the small Gopal caste of acrobats arc called Kabutari, and this further supports the hypothesis that Nat is rather an occupational term than the name of a distinct caste, though it is quite likely that there may be Nats who have no other caste.

The Badi or rope-dancer group again is an offshoot of the Gond tribe, at least in the tracts adjoining the Central Provinces. They have Gond septs as Marai, Netam, Wlka,^ and they have the damrii or drum used by the Gaurias or snake-charmers and jugglers of ChhattTsgarh, who are also derived from the Gonds. The Chhattisgarhi Dang-Charhas are Gonds who say they formerly belonged to Panna State and were supported by Raja Aman Singh of Panna, a great patron of their art. They sing a song lamenting his death in the flower of his youth. The Karnatis or Karnataks are a class of Nats who are supposed to have come from the Carnatic. Mr. Crooke notes that they will eat the leavings of all high castes, and are hence known as Khushhaliya or ' Those in prosperous circumstances.' *"

One division of the Nats are Muhammadans and seem to 2. Muhamniadan 1 Punjab Census Report (1881), ^ Asiatic Researches, \o\. \\\., \'iQ2), Nats, para. 588. by Captain Richardson.

- Tribes and Castes, art. Nat.

2 Tribes and Castes of Bengal, art. ^ Crooke, I.e., art. Nat. Beria. ^ Ibidem.

NAT 3. Social customs of ^ Qf ^j^g population. the Nats. o jr jr Their low status.

4. Acro- Ijatic performances. be to some extent a distinctive group. They have seven gotras—Chicharia, Damaria, Dhalbalki, Purbia, Dhondabalki, Karimki and Kalasia. They worship two Birs or spirits, Halaila Bir and Sheikh Saddu, to whom they sacrifice fowls in the months of Bhadon (August) and Baisakh (April). Hindus of any caste are freely admitted into their community, and they can marry Hindu girls. Generally the customs of the Nats show them to be the There is no offence which entails permanent expulsion from caste.

They will eat any kind of food including snakes, crocodiles and rats, and also take food from the hands of any caste, even it is said from sweepers. It is not reported that they prostitute their women, but there is little doubt that this is the case ; in the Punjab ^ when a Nat woman marries, the first child is either given to the grandmother as compensation for the loss of the mother's gains as a prostitute, or is redeemed by a payment of Rs. 30. Among the Chhattlsgarhi Dang-Charhas a bride-price of Rs. 40 is paid, of which the girl's father only keeps ten, and the remaining sum of Rs. 30 is expended on a feast to the caste.

Some of the Nats have taken to cultivation and become much more respectable, eschewing the flesh of unclean animals. Another group of the caste keep trained dogs and hunt the wild pig with spears like the Kolhatis of Berar. The villagers readily pay for their services in order to get the pig destroyed, and they sell the flesh to the Gonds and lower castes of Hindus. Others hunt jackals with dogs in the same manner. They eat the flesh of the jackals and dispose of any surplus to the Gonds, who also eat it.

The Nats worship Devi and also Hanuman, the monkey god, on account of the acrobatic powers of monkeys. But in Bombay they say that their favourite and only living gods are their bread-winners and averters of hunger, the drum, the rope and the balancingpole.^ The tight-rope is stretched between two pairs of bamboos, each pair being fixed obliquely in the ground and crossing each other at the top so as to form a socket over which the ' Ihbet.son, Punjab Census Report (1886), para. 588. 2 Bombay Gazetteer, vol. xx. p. 186, quoted in Mr. Crooke's article.

rope passes. The ends of the rope are taken over the crossed bamboos and firmly secured to the t^round by heavy pegs. The performer takes another balancing-pole in his hands and walks along the rope between the poles which are about 1 2 feet high. Another man beats a drum, and a third stands under the rope singing the performer's praises and giving him encouragement.

After this the performer ties two sets of cow or buffalo horns to his feet, which are secured to the back of the skulls so that the flat front between the horns rests on the rope, and with these he walks over the rope, holding the balancing-rod in his hands and descends again. Finally he takes a brass plate and a cloth and again ascends the rope. He places the plate on the rope and folds the cloth over it to make a pad. He then stands on his head on the pad with his feet in the air and holds the balancing-rod in his hands ; two strings are tied to the end of this rod and the other ends of the strings are held by the man underneath. With the assistance of the balancing-rod the performer then jerks the plate along the rope with his head, his feet being in the air, until he arrives at the end and finally descends again.

This usually concludes the performance, which demands a high degree of skill. Women occasionally, though rarely, do the same feats. Another class of Nats walk on high stilts and the women show their confidence by dancing and singing under them. A saying about the Nats is : Nat ka bachcha to kaldbazi hi karega ; or ' The rope-dancer's son is always turning somersaults.' ^ The feats of the Nats as tight-rope walkers used ap- 5. Sliding parently to make a considerable impression on the minds ^^^ ^^ of the people, as it is not uncommon to find a deified Nat, as a char called Nat Baba or Father Nat, as a village god.

A Natni crops.*^ or Nat woman is also sometimes worshipped, and where two sharp peaks of hills are situated close to each other, it is related that in former times there was a Natni, very skilful on the tight-rope, who performed before the king ; and he promised her that if she would stretch a rope from the peak of one hill to that of the other and walk across it he would marry her and make her wealthy. Accordingly the rope was stretched, but the queen from jealousy went and cut it

- Temple and Fallon's Hindustani Proverbs, p. 171.

VOL. IV U

half through in the night, and when the Natni started to walk the rope broke and she fell down and was killed. She was therefore deified and worshipped. It is probable that this legend recalls some rite in which the Nat was employed to walk on a tight-rope for the benefit of the crops, and, if he failed, was killed as a sacrifice ; for the following passage taken from Traill's account of Kumaon ^ seems clearly to refer to some such rite

" Drought, want of fertility in the soil, murrain in cattle, and other calamities incident to husbandry are here invariably ascribed to the wrath of particular gods, to appease which recourse is had to various ceremonies. In the Kumaon District offerings and singing and dancing are resorted to on such occasions.

In Garhwal the measures pursued with the same view are of a peculiar nature, deserving of more particular notice. In villages dedicated to the protection of Mahadeva propitiatory festivals are held in his honour. At these Badis or rope-dancers are engaged to perform on the tight-rope, and slide down an inclined rope stretched from the summit of a cliff to the valley beneath and made fast to posts driven into the ground.

The Badi sits astride on a wooden saddle, to which he is tied by thongs ; the saddle is similarly secured to the bast or sliding cable, along which it runs, by means of a deep groove ; sandbags are tied to the Badi's feet -sufficient to secure his balance, and he is then, after various ceremonies and the sacrifice of a kid, started off; the velocity of his descent is very great, and the saddle, however well greased, emits a volume of smoke throughout the greater part of his progress.

The length and inclination of the bast necessarily vary with the nature of the cliff, but as the Badi is remunerated at the rate of a rupee for every hundred cubits, hence termed a tola, a correct measurement always takes place ; the longest bast which has fallen within my observation has been twenty-one tolas, or 2 1 00 cubits in length. From the precautions taken as above mentioned the only danger to be apprehended by the Badi is from breaking of the rope, to provide against which the latter, commonly from one and a half to two inches in diameter, is made wholly by his own hand ; the material used is the 1 As. Res. vol. xvi., 1S2S, p. 213.

bhdbar grass. Formerly, if a Badi fell to the ground in his course, he was immediately despatched with a sword by the surrounding spectators, but this practice is now, of course, prohibited. No fatal accident has occurred from the performance of this ceremony since 181 5, though it is probably celebrated at not less than fifty villages in each year.

After the completion of the sliding, the bast or rope is cut up and distributed among the inhabitants of the village, who hang the pieces as charms on the eaves of their houses. The hair of the Badi is also taken and preserved as possessing similar virtues. He being thus made the organ to obtain fertility for the lands of others, the Badi is supposed to entail sterility on his own ; and it is firmly believed that no grain sown with his hand can ever vegetate.

Each District has its hereditary Badi, who is supported by annual contributions of grain from the inhabitants," It is not improbable that the performance of the Nat is a reminiscence of a period when human victims were sacrificed for the crops, this being a common practice among primitive peoples, as shown by Sir J. G. Frazer in Atlis, Adonis, Osiris.

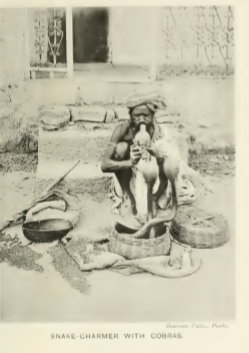

Similarly the spirits of Nats which are revered in the Central Provinces may really be those of victims killed during the performance of some charm for the good of the crops, akin to that still prevalent in the Himalayas, The custom of making the Nat slide down a rope is of the same character as that of swinging a man in the air by a hook secured in his flesh, which was formerly common in these Provinces, But in both cases the meaning of the rite is obscure. The groups who practise snake-charming are known as 6. Snake- Sapera or Garudi and in the Maratha Districts as Madari, •^'^^""^•'S' Another name for them is Nag-Nathi, or one who seizes a cobra.

They keep cobras, pythons, scorpions, and the iguana or large lizard, which they consider to be poisonous. Some of them when engaged with their snakes wear two pieces of tiger-skin on their back and chest, and a cap of tiger-skin in which they fix the eyes of various birds. They have a hollow gourd on which they produce a kind of music and this is supposed to charm the snakes. When catching a cobra they pin its head to the ground with a stick and then seize it in a cleft bamboo and prick out the poison292

fangs with a large needle. They thhik that the teeth of the iguana are also poisonous and they knock them out with a stick, and if fresh teeth afterwards grow they believe them not to contain poison. The python is called Ajgar, which is said to mean eater of goats.

In captivity the pythons will not eat of themselves, and the snake-charmers chop up pieces of meat and fowls and placing the food in the reptile's mouth massage it down the body. They feed the pythons only once in four or five days. They have antidotes for snake-bite, the root of a creeper called kalipdr and the bark of the karheya tree. When a patient is brought to them they give him a little pepper, and if he tastes the pungent flavour they think that he has not been affected by snake-poison, but if it seems tasteless that he has been bitten.

Then they give him small pieces of the two antidotes already mentioned with tobacco and 2-|- leaves of the 711111 tree ^ which is sacred to Devi. On the festival of Nag-Panchmi (Cobra's Fifth) they worship their cobras and give them milk to drink and then take them round the town or village and the people also worship and feed the snakes and give a present of a few annas to the Sapera. In towns much frequented by cobras, a special adoration is paid to them.

Thus in Hatta in the Damoh District a stone image of a snake, known as Nag-Baba or Father Cobra is worshipped for a month betore the festival of Nag- Panchmi. During this period one man from every house in the village must go to Nag-Baba's shrine outside and take food there and come back. And on Nag-Panchmi the whole town goes out in a body to pay him reverence, and it is thought that if any one is absent the cobras will harass him for the whole year. But others say that cobras will only bite men of low caste.

The Saperas will not kill a snake as a rule, but occasionally it is said that they kill one and cut off the head and eat the body, this being possibly an instance of eating the divine animal at a sacrificial meal. The following is an old account of the performances of snake-charmers in Bengal : '" " Hence, on many occasions throughout the year, the 1 Melia iiidica. by the Rev. Bihari Lai De, Calcutta 2 Bengali Festivals and Holidays, Review, vol. v, pp. 59, 60. iiiJinosc. Coiio., Dtti'y.

dread Manasa Devi, the queen of snakes, is propitiated by presents, vows and religious rites. In the month of Shrabana the worship of the snake goddess is celebrated with great eclat.

An image of the goddess, seated on a water-lily, encircled with serpents, or a branch of the snake -tree (a species of Euphorbia), or a pot of water, with images of serpents made of clay, forms the object of worship. Men, women and children, all offer presents to avert from themselves the wrath of the terrific deity.

The Mais or snakecatchers signalise themselves on this occasion. Temporary scaffolds of bamboo work are set up in the presence of the goddess. Vessels filled with all sorts of snakes are brought in. The Mais, often reeling with intoxication, mount the scaffolds, take out serpents from the vessels, and allow them to bite their arms. Bite after bite succeeds ; the arms run with blood ; and the Mais go on with their pranks, amid the deafening plaudits of the spectators.

Now and then they fall off from the scaffold and pretend to feel the effects of poison, and cure themselves by their incantations. But all is mere pretence. The serpents displayed on the occasion and challenged to do their worst, have passed through a preparatory state. Their fangs have been carefully extracted from their jaws. But most of the vulgar spectators easily persuade themselves to believe that the Mais are the chosen servants of Siva and the favourites of Manasa.

Although their supernatural pretensions are ridiculous, yet it must be confessed that the Mais have made snakes the subject of their peculiar study. They are thoroughly acquainted with their qualities, their dispositions, and their habits. They will run down a snake into its hole, and bring it out thence by main force. Even the terrible cobra is cowed down by the controlling influence of a Mai.

When in the act of bringing out snakes from their subterranean holes, the Mais are in the habit of muttering charms, in which the names of Manasa and Mahadeva frequently occur ; superstition alone can clothe these unmeaning words with supernatural potency. But it is not inconsistent with the soundest philosophy to suppose that there may be some plants whose roots are disagreeable to serpents, and from which they instinctively turn away. All snake-catchers of Bengal are provided with

a bundle of the roots of some plant which they carefully carry along with them, when they set out on their serpenthunting expeditions. When a serpent, disturbed in its hole, comes out furiously hissing with rage, with its body coiled, and its head lifted up, the Mai has only to present before it the bundle of roots above alluded to, at the sight of which it becomes spiritless as an eel. This we have ourselves witnessed more than once." These Mais appear to have been members of the aboriginal Male or Male Paharia tribe of Bengal.

Nat

(From People of India/ National Series Volume VIII. Readers who wish to share additional information/ photographs may please send them as messages to the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.)

Synonyms: Bazigar, Gulgulia, Sapera [Bihar and/or Jharkhand] Dimrichia, Jagmores, Kanaraha, Kanaujia, Khatanga, Lakarabadi, Madraulaha, Nimauraha, Pachbaria [Madhya Pradesh and/or Chhattisgarh] Natta [West Bengal] Badi, Bazigar, Dang-Charha, Karnati, Sapera [Russell & Hiralal] Groups/subgroups: Banwaria, Chhabhayia, Gulgulia, Kathbhangi, Kazarhatia, Kongarh, Kororhia, Lodhra, Nituria, Pusthia, Rarhi, Rathor, Tikulhara, Tirkuta [Bihar and/or Jharkhand] Bratya Kshatriya, Bratya Nat, Gawar Nat, Karwal Nat, Manchrang, Nat, Sratya Nat [West Bengal] Titles: Prasad [Madhya Pradesh and/or Chhattisgarh] Surnames: Gandharva, Lai, Mangta, Prasad, Rathor [Bihar and/or Jharkhand] Nat, Prasad [Madhya Pradesh and/or Chhattisgarh] Barman, Nandi, Natta, Roy, Sarkar [West Bengal]

- Exogamous groups (gotra): Chicharia, Damaria, Dhalbalki, Dhondabalki, Kalasia, Karimki, Purbia [Russell & Hiralal]

Oimrichiya, Jagmora, Kanaraha, Kanaujia (dervied from place name), Khatanga, Madraulaha, Nadbor, Nimauraha, Pachbariya [Madhya Pradesh and/or Chhattisgarh] Banuth in Punjab and Himachal Pradesh, Bero, Chango [H.A. Rose] Bahunaina, Deodianaik, Gauharna, Ghughasiya, Jaghat (Badi), Jhinjhariya, Jimichhiya, Makriyana (Bajaniya), Marai, Neshtri, Neta, Netam, Oika, Panchhiya, Sarai (Kalabaz), Ure [W. Crooke] Gotra: Bharadwaj [Bihar and/or Jharkhand] Alimman, Bharadwaj, Kashyap [West Bengal]

- Sections: Badi Nat, Bajaniya Nat, Brijbasi, Byadha Nat, Chamazmangta, Deodinaik, Eastern, Gagoliya, Gara Nat,

Gonha, Gouharna (Karnataka), Gual, Jogila, Kabutara, Kalabar, Kalabaz, Kapariya Karnataka Nat, Kashmiri Nat, Lohangi Nats, Mahawat, Mahawat Nat, Makriyana, Malar Nat, Mirdaha, Nat, Rathaur, Sanpaneriya, Sapera, Suganaik, Tasmabaz, Turkata Pahlwan (Mahawat) Waniawaraha in the districts of North Western Provinces [W. Crooke]

PART B: After 1947

Status in 2019

Arvind Chauhan, Dec 21, 2019 Times of India

From: Arvind Chauhan, Dec 21, 2019 Times of India

Of the many things she had been taught by her mother-in-law, one had left a lasting albeit unsettling impression: “When you go up on stage, you are not there for yourself. People want to celebrate and you let them. If something goes wrong, you deal with it.” Pooja was 12 then. Her mother-inlaw, no older than 30 herself at the time, had just retired as a dancer. It was Pooja’s turn to take the stage.

Girls from the Nat community are married off when they are barely in their teens and most become mothers by the time they turn 18. Older women said only the “married” ones become dancers to support their families. “It’s a way of life they are prepared for,” said Shanti, a 70-year-old former dancer.

Pooja, now 28, travels 300 km from her village in Badaun twice a year to Hamirpur (both places in UP), where a tiny settlement 15 km outside the town comes alive during the wedding season. Young women practise their dance routines and exchange notes on makeup. Their children run around while their husbands stay hooked to their phones, settling on itineraries. It is a busy time.

The recklessness that marks celebrations in these parts may have taken a while for Pooja to come to terms with, but after doing this over and over she learnt quickly enough. “Men can do anything when they get drunk,” she said.

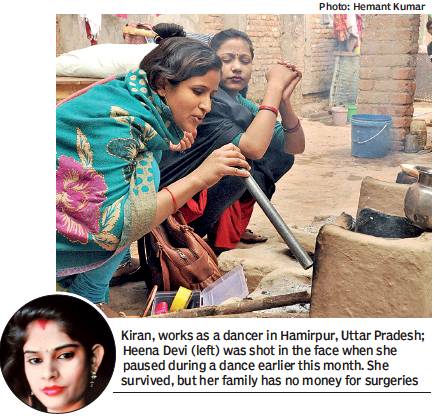

Weeks ago, Heena Devi, a 20-year-old dancer, was shot in the face by a man in attendance when she paused for a moment to catch her breath after a halfhour performance at a Hamirpur wedding.

It blew her jaw off, turning her once beautiful face into a mangled blob of flesh.

Varsha, 26, was inches away from Heena when the shots were fired. She has all but fallen silent since. She would rather not get back on stage, but she has no choice. “She has three children, a husband and a mother-in-law to support. It won’t be possible for her to stop dancing. What else can she do?” said Srikrishan, Heena’s brother-in-law. Varsha did not want to speak.

Safety is a perpetual concern. If there is no violence one day, there is physical abuse and molestation the other. “We judge the situation and mould ourselves in many ways,” said Reena, 20, a mother of three from Ramnagar in Agra. What does that entail? “We dance in front of hundreds of drunken men. They may be married with children but they hurl abuses if they don’t like a song, want to get on stage, touch us, grope us.”

The dancers get used to the risks. The police don’t take it very seriously either. “We never receive any complaint from them. We do tell them they should be alert,” said Shriprakash Yadav, a local police officer, handing the responsibility of their safety back to the women. “They visit each village for a brief period of time. There is a lot of travelling in their line of work. But they can contact the local police if they get into trouble,” he added to explain why police “can do little” for their safety.

Heena’s family said police did not help take her to the hospital. Her assailants, on the other hand, got away after shooting at her and were at large for about two weeks until social media picked up the story. A week after Heena was shot at, a 27-year-old Mumbaibased wedding dancer was gang-raped in Chhattisgarh. Days before that, a Rajasthanbased dancer had been raped by two men at Nagaur. Earlier this year, a dancer was raped and murdered in Bihar. And it was in Uttar Pradesh three years ago that a dancer was gang-raped at gunpoint by four pharmaceutical company executives. In all cases, the men had decided that hiring dancers for a performance entitled them to sex.

Locals brush it aside as an occupational hazard. As one of the men in Hamirpur said: “They know what they are getting into.” Husbands and male kin of the dancers are unwilling or unable to do much. After all, who will come for the shows if the performances are fenced by a ring of morality. A brother of one of the women only said “the audience gets unruly sometimes” when asked about the dancers’ exposure to risk.

The women, too, are unwilling to talk openly about the threat of sexual assault. “Happens. Not every day,” said Neetu, a 37-year-old former dancer. She has ceded the stage to her 21-year-old daughter-in-law, Naina, and runs the troupe now. But women in the community are beginning to look beyond accepted frameworks for their lives, or at least for their children.

“We may be the last generation. The risk is not worth it. I send my girls to school so they are not stuck without options,” said Pooja, determined that the advice thrust on her by her mother-in-law will not be handed down.

PERFORMERS SINCE AGES

Nats trace origins to Rajasthan and have been entertainers for centuries

A semi-nomadic group of singers, jugglers and dancers, it was declared “criminal tribe” by British in 19th C. Next blow came when zamindari system ended; community lost its patrons and many of its women turned to sex work to feed families

Most come from Etawah, Badaun, Agra, Aauriya, Farrukhabad and Etah in UP

About 20 weddings can bring in Rs 2 lakh for a troupe or “orchestra”, as it is locally known, in a season