North- East India: Political history

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

The concept of a Northeast India

1971 onwards

Sanjib Baruah, Dec 30, 2023: The Indian Express

The North-Eastern Areas (Reorganisation) Act and the North-Eastern Council Act were enacted by Parliament on December 30, 1971. Together, they gave birth to Northeast India as an officially recognised and named entity that we know today.

With these, Northeast India “emerged as a significant administrative concept replacing the hitherto more familiar unit of public imagination, Assam,” B P Singh, a former senior bureaucrat who served as the Governor of Sikkim from 2008-13, wrote in The Problem of Change: A Study of North-East India (1997).

Today, ‘Northeast India’, or just ‘the Northeast’, is commonly used by Indians to refer to the diverse region, with its inhabitants becoming ‘Northeasterners’, regardless of how they themselves self-identify. Yet the term took root only in the 1970s.

Here is the story of the ‘invention’ of Northeast India.

The Northeast

Northeast India officially comprises eights states — Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim, and Tripura — which are a part of the North-Eastern Council, a statutory advisory body that plays a role in development planning, and region-level policy making.

Pre-Independence, five of these eight present-day states (Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Mizoram) were a part of colonial Assam. Manipur and Tripura were princely states, with resident British political officers answering to the governor of Assam.

Sikkim, the most unique of the eight, was juridically independent but under British paramountcy. It became an independent country in 1947, before being annexed by India in 1975. In 2001 Sikkim was made a member of the North Eastern Council, and thus officially a part of the Northeast.

Part of the colonial “frontier”

Colonial Assam was a “frontier province” in British India. Like the North West Frontier Province (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in present-day Pakistan), the political legal setup in the province was very different from the rest of the country.

Direct rule was limited to territories behind the administrative border, known as the ‘settled districts’ of Assam (most of present-day Assam and Sylhet, now in Bangladesh). These densely populated districts were — and still are — the region’s economic heartland, with thriving tea, coal, and oil industries emerging in the nineteenth century.

Beyond these districts lay the so-called ‘excluded areas’ or the ‘Hill areas’, controlled by various tribes, with minimal presence of the colonial state. These areas were (and still are, relatively speaking) sparsely populated, and provided a buffer zone between the ‘settled districts’ and the international border.

For instance, like the Federally Administered Tribal Area (FATA) located between the ‘settled districts’ of the NWFP and the international border with Afghanistan, the North East Frontier Tracts (modern-day Arunachal Pradesh and a part Nagaland) was carved out in 1914, and located between the ‘settled districts’ of Assam, and the international border with Tibet and Burma.

National security concerns, and becoming part of the Indian state

Thus, at the time of Independence, the region was unlike any other territory India inherited from the British. Northeast India, as an official place-name, is born out of the postcolonial Indian state’s attempts to turn this imperial frontier space into the national space of a “normal sovereign state.”

To do this, the Indian state made a series of ad hoc decisions to institute a new governance structure that eventually replaced the administrative setup of a colonial frontier province. Their foremost concern was the nebulous concept of national security. After 1947, 98 per cent of the region’s borders became international (with China, Myanmar, Bangladesh, and Bhutan). A roughly 22 km wide land corridor in Siliguri, often referred to as the “chicken’s neck”, became its sole physical connection with the rest of India.

By the 1960s, national security concerns were further heightened. India lost a border war with China in 1962, with the Chinese entering all the way into Assam, and the movement for Naga independence was in full swing. India and Pakistan fought a war in 1965, and the Mizo rebellion began the following year. Fears about the challenge to national security if the country’s external and domestic enemies were to join hands, became jarringly immediate.

That the state of Nagaland was created a year after the China War is no accident. By making Nagaland into a state, Indian officials hoped to create Naga stakeholders in the Indian dispensation that would help quell the Angami Zapu Phizo-led rebellion. In retrospect it turned out to be the first step toward replacing the administrative structure of the frontier province with a new structure of governance.

With the North-Eastern Areas (Reorganisation) Act of 1971, Manipur and Tripura, previously union territories, were given statehood. Meghalaya was carved out of two previously autonomous districts within Assam, and so was the union territory of Mizoram. The erstwhile North East Frontier Agency became the union territory of Arunachal Pradesh. Both Mizoram and Arunachal would be granted full statehood in 1987.

The weight of a name

When using a directional name, it is perhaps always a good idea to ask, “Where is it we really start from, where is the place that enunciates this itinerary”? For “the Northeast”, the point of reference is clear: it is the Indian “heartland”. The directional place-name highlights the peculiar hierarchical relation that has developed between this region and the nation since Independence.

There is perhaps no better evidence of the region’s othering than the normalisation of the racialized category Northeasterner. While the term is hardly ever used for self-identification (one rarely hears someone say “I am a Northeasterner” rather than “I am a Naga/Khasi/Meitei/Kuki”), it nonetheless has found its way into commonspeak, especially outside the region. Moreover, Northeasterners have long complained of being subjected to racial slurs based on phenotypic stereotypes. Many find themselves non-recognized and misrecognized, hailing from places such as China, Nepal, Thailand, or Japan, or as ‘lesser Indians’ rather than as equal citizens.

Since the new governance structure and its naming were the result of a process of muddling through — and not much thought was given to its possible consequences — it was perhaps inevitable that it would create as many new problems as it would solve.

Sanjib Baruah is the Andy Matsui Distinguished Professor of the Humanities at the Asian University for Women in Chattogram, Bangladesh. He authored ‘In the Name of the Nation: India and its Northeast’ in 2020.

Peace accords

1986-2022

Jayanta Kalita, Sep 23, 2022: The Times of India

From: Jayanta Kalita, Sep 23, 2022: The Times of India

From: Jayanta Kalita, Sep 23, 2022: The Times of India

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led Centre has signed a series of peace accords with militant groups in the past few years in its bid to achieve “permanent peace” in the Northeast. The latest one – a tripartite agreement involving the Centre, the Assam government and eight small Adivasi groups, which had laid down arms a decade ago – was inked on September 15.

This comes at a time when the government is struggling to break the deadlock in the Naga peace process involving the oldest insurgent group in the region and probably working towards finetuning a peace agreement with the pro-talk faction of the United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA).

The 1986 Mizoram Accord signed by the Rajiv Gandhi government, which brought an end to the Mizo insurgency and led to the creation of a separate state, is widely seen as the only successful peace agreement in the Northeast. Since then, successive central governments have failed to address any major separatist issue in the region.

For the record, more than a dozen militant outfits in the region announced a ceasefire between 1997 and 2013, mostly during the tenure of the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA). So, what are the recent ‘peace accords’ all about?

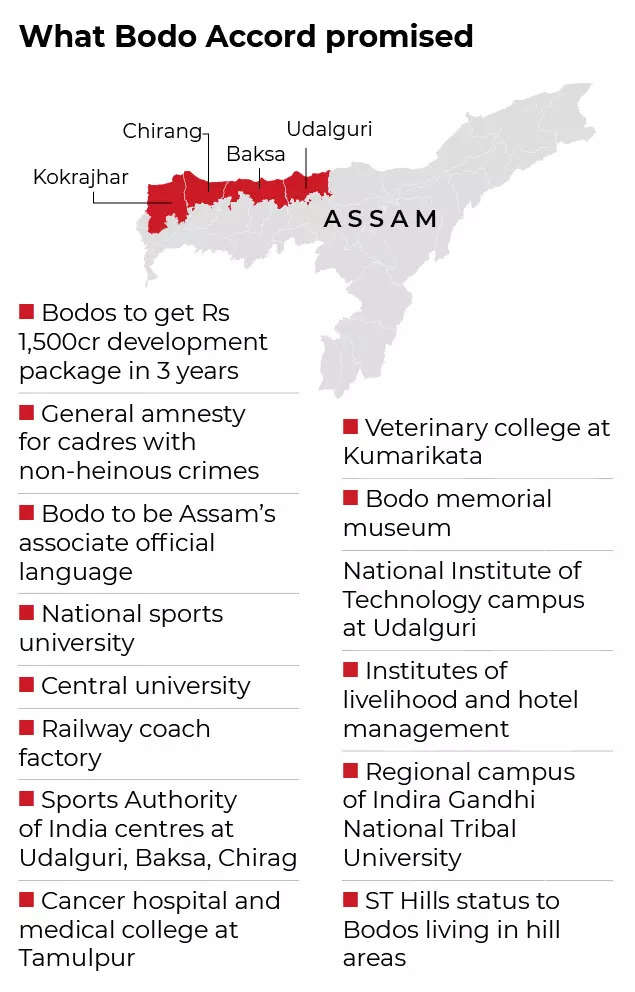

The Bodo Accord

In January 2020, the Centre signed a peace pact with an aim to end the decades-long armed conflicts in areas dominated by the indigenous Bodo community in Assam. The accord promised to replace the existing Bodoland Territorial Area Districts (BTAD) with Bodoland Territorial Region (BTR), which will have more financial and administrative powers including the power to appoint deputy commissioners and superintendents of police.

The signatories included the National Democratic Front of Bodoland (NDFB), and the All Bodo Students’ Union (ABSU), then led by Pramod Boro, besides the Assam government. The NDFB had led an armed separatist movement since the late 1980s, seeking to create a “sovereign Bodoland”. Last year, the Assam government approved a Rs 160-crore rehabilitation package for 4,036 Bodo rebels who laid down their arms.

The Bodos are the third-largest linguistic community in the state after the Assamese and the Bengalis. There are 14.16 lakh Bodo speakers out of the 3.1 crore population in Assam, according to the 2011 Census.

The political dividend: Almost a year after the accord, Pramod Boro, a former student leader, became the chief of the Bodoland Territorial Council (BTC) elections. The BTC, an autonomous body under the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution, is now ruled by a coalition of the Boro-led United People’s Party Liberal (UPPL), the BJP and other allies. The biggest highlight of that election was the significant rise in BJP’s seats, from just one in 2015 to 9 in 2020. The accord promises to increase the seats in the council from the existing 40 to 60.

The Karbi Anglong Accord

Last September, a tripartite accord was signed with six rebel groups of Assam. With this, over 1,000 armed cadres abjured violence and joined the mainstream of society. A special development package of Rs 1,000 crore over five years would be given by the Centre and the Assam government to undertake specific projects for the development of tribal-dominated Karbi Anglong region.

The Memorandum of Settlement (MoS) also promised greater devolution of autonomy to the Karbi Anglong Autonomous Council (KAAC), protection of identity, language, culture, of Karbi people and focussed development of the Council area, without affecting the territorial and administrative integrity of Assam.

Political dividend: Months later, the BJP won all the 26 seats in the KAAC polls, its biggest electoral victory. Like the BTC, KAAC also comes under the Sixth Schedule.

Pact with Adivasi militants

On September 15 this year, five Adivasi militant outfits and three splinter groups signed an agreement with the Centre and the Assam government. These groups abjured violence a decade ago and have been staying at designated camps.

It was in the late 1990s when some Adivasi groups took up arms in the wake of major conflicts with the Bodos, the largest plains tribe in Assam. About 200 people were killed and over 2 lakh people from both communities were displaced in those clashes. The Adivasis in Assam are referred to as the tea community as they mostly work in more than 800 tea gardens of Assam. The Adivasis along with five other indigenous communities – Tai Ahom, Matak, Moran, Sootea and Koch-Rajbongshi – have been demanding Scheduled Tribe (ST) status for decades. The political dividend: The latest accord is likely to pave the way for the Adivasis to be categorised as ST, like their counterparts in eastern and central India. And this could be another shot in the arms for the ruling BJP given the party has made deep inroads into the tea belt constituencies since 2014 Lok Sabha polls. In the 2021 Assam assembly elections, the BJP won 27 of the 37 seats in the Adivasi-dominated areas. Hurdles and delays The National Socialist Council of Nagalim (Isak-Muivah) or NSCN (I-M), with whom the Government of India signed a framework agreement with much fanfare in 2015, now alleges trust deficit in the peace process. More than 100 rounds of talks have been held since the oldest rebel group of the region announced a ceasefire in 1997.

But in June, the talks broke down after the Centre’s representative – A K Mishra – allegedly excluded three key points, earlier agreed to by his predecessor R N Ravi, from the final proposal submitted to the NSCN (I-M), T R Zeliang, chairman of the United Democratic Alliance and former chief minister of Nagaland told The Hindu. These points or demands are – a separate constitution, integration of Naga-inhabited areas of Assam, Manipur and Arunachal Pradesh with Nagaland and the setting up of a regional autonomous council, the report said. Besides, there has been no clarity if the Centre would agree to the demand for a separate Naga flag in the wake of the abrogation of Article 370 that gave special powers to the erstwhile state of J&K.

Similarly, in Assam, the pro-talk faction of the ULFA is awaiting an agreement with the government. ULFA chairman Arabinda Rajkhowa recently told TOI that “all our core issues (demands) were discussed threadbare with previous interlocutors. There is nothing more to discuss, as such.”

One of the core demands of the rebel outfit, which joined the peace process over a decade ago, is the constitutional safeguard for Assam’s indigenous people. The issue is linked to the historic Assam Accord in 1985, the signing of which brought an end to the six-year anti-foreigner movement in Assam.

The Centre may be able to take a call on this after the Supreme Court gives its verdict in petitions challenging the constitutional validity of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act or CAA, which seeks to grant citizenship to non-Muslim migrants fleeing religious persecution in Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan who entered India on or before December 31, 2014.

The All Assam Students Union (AASU), one of the petitioners, has argued that CAA is in conflict with the Assam Accord, as it stipulated that foreigners who entered the state after March 24, 1971, irrespective of their religious affiliation, must be deported.

With both the Naga and ULFA issues stuck, the ruling BJP seems to be using smaller deals to send out a message that after the withdrawal of Article 370, it is serious about addressing the problems pertaining to India’s northeast. The question is – can quick-fixes help bring permanent peace given the insurgency issue in the region is far more complex and different than that of J&K?

With both the Naga and ULFA issues stuck, the smaller deals may be helping the ruling BJP send out a message that after the withdrawal of Article 370, it is serious about addressing the problems pertaining to India’s northeast.

Political parties’ fluctuating fortunes

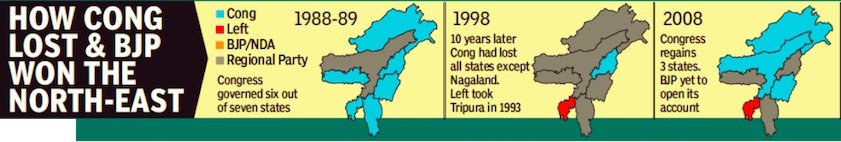

1988- 2018: How the Congress lost and BJP won the NE

From: March 4, 2018: The Times of India

From: March 4, 2018: The Times of India

See graphics:

1988- 2008: The fluctuating fortunes of the Congress in North- East India

2016- 2018: How the Congress lost and BJP won the NE

MLAs’ assets and average age

MLAs’ assets and average age

The number of female MLAs

From: March 4, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic:

Meghalaya, Nagaland, Tripura: 2018

MLAs’ assets and average age

The number of female MLAs

Migrants from neighbouring countries

2019 Dec: agitations on the Citizenship issue

NEW DELHI: The country's northeast region has been witnessing widespread protests after both houses of Parliament approved the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill (CAB) that seeks to provide Indian nationality to six non-Muslim communities -- Hindus, Sikhs, Christians, Parsis, Jains and Buddhists -- fleeing persecution from Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh and who moved to India before December 31, 2014. It does not, however, extend to Rohingya Muslim refugees who fled persecution in Myanmar.

The bill cleared the Rajya Sabha test on Wednesday. President Ram Nath Kovind on Thursday gave his assent to the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, 2019, turning it into an Act. According to an official notification, the Act comes into effect with its publication in the official gazette on Thursday.

Why northeast is unhappy

There is fear in the northeast that granting citizenship to ordinary refugees will undermine the ethnic communities living in these regions. The bill has sparked widespread and violent protests across the region, including Assam, Tripura, Manipur, Nagaland, Meghalaya and Arunachal Pradesh. Several civil society groups, students' unions and political parties contend that CAB would threaten the interests of indigenous tribal people and dilute their culture and political sway.

Opposition parties as well as protesters say the bill is against the secular fabric of India's Constitution and will allow the influx of lakhs of foreigners from these three countries into a region already "burdened" with illegal Bangladeshis.

Assam turns into a war zone

Assam, in particular, is on the boil. Despite curfew on Thursday, thousands of people took to the streets of Guwahati, prompting police to open fire, even as protests against the contentious bill are intensifying in the state. Police opened fire in Lalung Gaon area in Guwahati after stones were hurled by protesters. The agitators claimed that at least four persons were injured in the shooting. Police also fired in the air in several other areas of the city, including the Guwahati-Shillong Road which turned into a war zone.

Students' body AASU and peasants' organisation KMSS called for a mega gathering at Latashil playground in the city, which was attended by hundreds of people. Many prominent personalities from the film and music industry, including icon Zueen Garg, joined the gathering along with college and university students.

Leaders of the AASU and the North East Students' Organization (NESO) said they will observe December 12 as 'Black Day' every year in protest against the passage of the bill in Parliament.

Sporting activities took a hit in Assam's capital where an Indian Super League (ISL) football game and a Ranji Trophy cricket match were suspended on Thursday owing to the unrest.

Kamrup district witnessed an absolute shutdown. Police said they had to fire three rounds in the air in Rangia town as protesters threw stones and burnt tyres. Agitators were also baton-charged at several places in the town.Police also fired in the air in Golaghat district to disperse protesters who blocked the NH 39, officials said. Tea garden workers stopped work in Lakhimpur and Charaideo districts and also at Numaligarh in Golaghat district and some areas in Tinsukia district.

All educational institutions across the state are closed and internet services are disrupted. Five columns of the Army have been deployed in different parts of the state and are conducting flag marches in Guwahati, Tinsukia, Jorhat and Dibrugarh. Flights and trains to and from Assam have been cancelled.

Tripura limps towards normalcy

Following protests since Monday when the bill was cleared in the Lok Sabha, the situation in Tripura on Thursday was mostly normal, barring stray incidents of violence in three of its eight districts in the past 24 hours.

"Troopers of Assam Rifles, Border Security Force (BSF) and Tripura State Rifles (TSR) were deployed in Dhalai district. No fresh incident was reported on Thursday. Only some rumour mongers trying to spread fake news," Brahmneet Kaur, DM and Collector(Dhalai) told news agency IANS.

What the government says

The government may work out a compromise in connection with the concerns of northeast states. Formulations like provision of citizenship not leading to residency status in the smaller northeast states have been discussed.

The legislation exempts from its purview tribal areas of Assam, Meghalaya, Mizoram or Tripura as included in the Sixth Schedule to the Constitution and areas covered under The Inner Line, notified under Bengal Eastern Frontier Regulation, 1873.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has said the bill would have no impact on the country's citizens and government would safeguard their language, culture and identity "under all circumstances".

Today, I appeal to my brothers and sisters of Assam to have faith in Modi. No harm will come to them and their tradition, culture and way of living," he said on Thursday.

CAB is 'divisive tool': Prafulla Mahanta

The bill is "divisive tool" that will damage the composite culture of the northeast and must be immediately scrapped, two-time Assam chief minister Prafulla Kumar Mahanta has said. CAB has been brought in to create a Hindu-Muslim divide, said the former student leader who led a six-year movement demanding deportation of illegal Bangladeshis in the late 1980s.

"The indigenous people of Assam and the northeast are staring at an existential threat to their composite culture. The proposed law will open the floodgates of illegal foreigners to the region. We are determined to fight it out till our last breath," Mahanta told PTI.

"Every nook and corner in Assam is erupting in spontaneous protests against the black bill. The people of Assam are determined to defeat this divisive and unconstitutional tool called CAB. We will not relent till it is scrapped," Mahanta added.

"The home minister of the country has not been able to understand the seriousness of the issue. CAB has been brought in to create divisions between Hindus and Muslims. Assam has been known for strong unity among all communities and the BJP is now trying to damage it," Mahanta said.

AGP, BJP's Assam ally, stance

In January 2018, Asom Gana Parishad (AGP), BJP's ally in Assam, pulled our of the NDA after Lok Sabha passed the earlier version of the bill, which BJP had introduced in Parliament in 2016. When the bill lapsed in the Lok Sabha, AGP returned to the the NDA fold. In recent days, AGP has hinted at a change in its stance on the bill.

"We have to move forward with the reality -- neither can we expel lakhs of illegal immigrants nor will Bangladesh ever take them back. We had our government twice in the past, but we could not even identify the illegal migrants. Unfortunately, the Assam Accord has only gathered dust for over 34 years," AGP leader and Assam minister Atul Bora said.

Before CAB, there was NRC

Just four months ago, there was widespread criticism against the Centre over the National Register of Citizens (NRC), which was prepared in Assam to identify Indian citizens living in the state since March 24, 1971 or before. Of the 3.3 crore applicants, over 19 lakh people were excluded from the final NRC which was published around three-and-a-half months ago. CAB could provide protection for many of the Hindus left off Assam's NRC.

How CAB was passed

CAB was passed by the Rajya Sabha on Wednesday, with 125 members of the Upper House voted in favour while 99 MPs voted against the bill. The Shiv Sena did not participate in the voting, which helped the government by bringing down the House’s effective strength marginally. The bill sailed through the Lok Sabha on Monday with a 334-106 vote count.