North Indian Popular Religion: 07a –Bhairon and Ganesa

This article is an extract from

THE POPULAR RELIGION AND FOLK-LORE OF NORTHERN INDIA BY BENGAL CIVIL SERVICE

WESTMINSTER ARCHIBALD CONSTABLE & CO.

Indpaedia is an archive. It neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this colonial article. |

Worship of Bhairon

Bhûmiya, again, is often confounded with Bhairon, another warden godling of the land; while, to illustrate the [108]extraordinary jumble of these mythologies, Bhairon, who is almost certainly the Kâro Bairo (Kâl Bhairon) of the Bhuiyas of Keunjhar, is identified by them with Bhîmsen.44

Bhairon has a curious history. There is little doubt that he was originally a simple village deity; but with a slight change of name he has been adopted into Brâhmanism as Bhairava, “the terrible one,” one of the most awful forms of Siva, while the female form Bhairavî is an equivalent for Devî, a worship specially prevalent among Jogis and Sâktas. On the other hand, the Jainas worship Bhairava as the protector or agent of the Jaina church and community, and do not offer him flesh and blood sacrifices, but fruits and sweetmeats.45

In his Saiva form he is often called Svâsva, or “he who rides on a dog,” and this vehicle of his marks him down at once as an offshoot from the village Bhairon, because all through Upper India the favourite method of conciliating Bhairon is to feed a black dog until he is surfeited. One of his distinctive forms is Kâl Bhairon, or Kâla Bhairava, whose image depicted with his dog is often found as a sort of warden in Saiva temples. One of his most famous shrines is at Kalinjar, of which Abul Fazl says “marvellous tales are related.”46 He is depicted with eighteen arms and is ornamented with the usual garlands of skulls, with snake earrings and snake armlets and a serpent twined round his head. In his hands he holds a sword and a bowl of blood. In the Panjâb he is said to frighten away death, and in Râjputâna Col.

Tod calls him “the blood-stained divinity of war.”47 The same godling is known in Bombay as Bhairoba, of whom Mr. Campbell48 writes—“He is represented as a standing male figure with a trident in the left hand and a drum (damaru) in the right, and encircled with a serpent. When thus represented he is called Kâla Bhairava. But generally he is represented by a rough stone covered over with oil and red lead. He is said to be [109]very terrible, and, when offended, difficult to be pleased.

By some he is believed to be an incarnation of Siva himself, and by others as a spirit much in favour with the god Siva. He is also consulted as an oracle. When anyone is desirous of ascertaining whether anything he is about to undertake will turn out according to his wishes, he sticks two unbroken betel-nuts, one on each breast of the stone image of Bhairava, and tells it, if his wish is to be accomplished, that the right or left nut is to fall first. It is said, like other spirits, Bhairava is not a subordinate of Vetâla, and that when he sets out on his circuit at night, he rides a black horse and is accompanied by a black dog.”

In the Panjâb he49 is usually represented as an inferior deity, a stout black figure, with a bottle of wine in his hand; he is an evil spirit, and his followers drink wine and eat meat. One set of ascetics, akin to the Jogis, besmear themselves with red powder and oil and go about begging and singing the praises of Bhairon, with bells or gongs hung about their loins and striking themselves with whips.

They are found mainly in large towns, and are not celibates. Their chief place of pilgrimage is the Girnâr Hill in Kâthiawâr. That very old temple, the Bhairon Kâ Asthân near Lahore, is so named from a quaint legend regarding Bhairon, connected with its foundation. In the old days the Dhînwâr girls of Riwâri used to be married to the godling at Bandoda, but they always died soon after, and the custom has been abandoned. We shall meet later on other instances of the marriage of girls to a god.

As a village godling Bhairon appears in various forms as Lâth Bhairon or “Bhairon of the club,” which approximates him to Bhîmsen, Battuk Bhairon or “the child Bhairon,” and Nand Bhairon, in which we may possibly trace a connection with the legend of the divine child Krishna and his foster-father Nanda. In Benares, again, he is known as Bhaironnâth or “Lord Bhairon,” and Bhût Bhairon, “Ghost Bhairon,” and he is regarded as the deified magistrate [110]of the city, who guards all the temples of Siva and saves his votaries from demons.50

But in his original character as a simple village godling Bhairon is worshipped with milk and sweetmeats as the protector of fields, cattle and homestead. Some worship him by pouring spirits at his shrine and drinking there; and on a new house being built, he is propitiated to expel the local ghosts.

He is respected even by Muhammadans as the minister of the great saint Sakhi Sarwar, and in this connection is usually known as Bhairon Jati or “Bhairon the chaste.”51 But as we have seen, he is becoming rapidly promoted into the more respectable cabinet of the gods, and his apotheosis will possibly finally take place at the great Saiva shrine of Mandhâta on the Narmadâ, with which a local legend closely connects him.52 All over Northern India his stone fetish is found in close connection with the images of the greater gods, to whom he acts the part of guardian, and this, as we have already seen, probably marks a stage in his promotion.

He has, according to the last census, only five thousand followers in the Panjâb, as compared with one hundred and and seventy-five thousand in the North-Western Provinces.

Worship of Ganesa

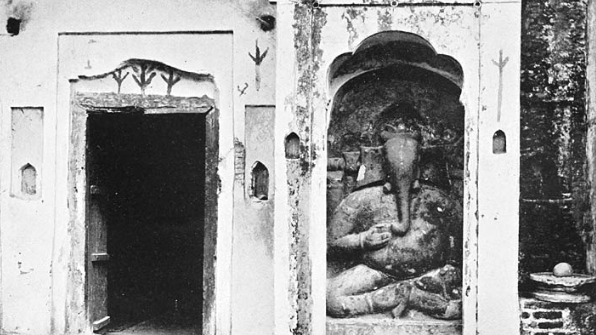

On pretty much the same stage as these warden godlings whom we have been considering is Ganesa, whose name means “lord of the Ganas” or inferior deities, especially those in attendance on Siva. He is represented as a short, fat man, of a yellow colour, with a protuberant belly, four hands, and the head of an elephant with a single tusk. Pârvatî is said to have formed him from the scurf of her body, and so proud was she of her offspring that she showed him to the ill-omened Sani, who when he looked at him reduced his head to ashes. Brahma advised her to replace the head with the first she could find, and the first she found [111]was that of an elephant.

Another story says that Ganesa’s head was that of the elephant of Indra, and that one of his tusks was broken off by the axe of Parasurâma. Ganesa is the god of learning, the patron of undertakings and the remover of obstacles.

Hence he is worshipped at marriages, and his quaint figure stands over the house door and the entrance of the greater temples. But there can be little doubt that he, too, is an importation from the indigenous mythology. His elephant head and the rat as his vehicle suggest that his worship arose from the primitive animal cultus.