Noshaba Shehzad

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

A brief profile

As in 2023

Sandeep Rai, March 20, 2023: The Times of India

From: Sandeep Rai, March 20, 2023: The Times of India

From: Sandeep Rai, March 20, 2023: The Times of India

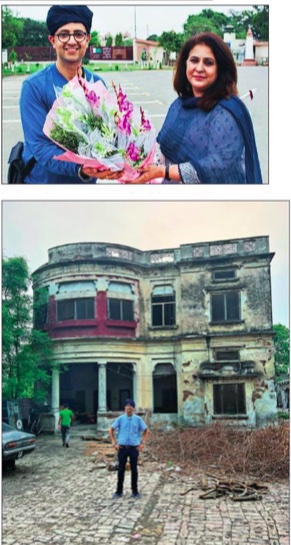

Last July, 90-year-old Reena Chhibber Varma stood alone in front of a sprawling bungalow in Rawalpindi’s College Road. It was the family home she had had to abandon for a new country at the age of 15. “It was maintained well but it belongs to someone else now,” the Pune-based nonagenarian said with tears rolling down. Among those who helped Reena visit her ancestral home after 75 years was Noshaba Shehzad, a 47-year-old Lahore resident who has made it her mission to help Indians who had fled Pakistan after Partition see their old homes.

Haunted By The Past

Noshaba grew up in Talagang, a town in Chakwal district of Pakistan’s Punjab province. The large house she lived in belonged to a Hindu family that had entrusted it to her family at the time of Partition. The district had been home to a large number of wealthy Hindus who were displaced overnight and lost their homes and businesses in 1947.

“Ours was a close-knit community that had lived together for centuries. The Partition actually cut off this umbilical cord. . . People from both sides were suddenly left with nothing,” Noshaba told TOI from across the border. She had heard painful stories of the Partition from her father, who died last November aged 90. “He used to remember Shakuntala, his 16-year-old neighbourhood friend, every day. ”

When the exodus started, Shakuntala hid in Noshaba’s family home for three days. “She was found in our house but our family could not keep her as it was illegal, and she was unwilling to leave. She had to be forcefully transported to a camp amid tears and cries from both sides,” Noshaba narrated what she had heard from her late father.

Years passed, Noshaba got married in Islamabad and became a successful exporter of agri products. However, the stories of 1947 haunted her. She travelled abroad extensively to study agriculture in foreign universities, “and made a lot of Indian friends, particularly from the Sikh community. And most of them had painful memories to share. ”

In 2018, Noshaba moved to Lahore, her husband’s hometown, and has helped more than 200 people of Indian origin visit Pakistan since then. “Lahore is the cradle of Sikhism. The city still hosts hundreds of abandoned gurdwaras and ruins of oncetall houses. I have a special affinity for these crumbling structures. Thebricks of fallen walls speak to me of the pain of those who had to leave forever. . . Every time I visit them, I feel how desperate those people and their children must be to visit their ancestral place,” Noshaba said. She met like-minded people and became part of the social media-driven IndiaPakistan Heritage Club that she manages with her associates Imran Williams and Zahid Karmanwala. It has more than 1. 45 lakh members from both nations. “Interacting in this group, I realised how desperately people longed to come to Pakistan. I also met a lot of pilgrims from India at the Kartarpur corridor. Many of them, particularly the older lot, cry and beg to be taken to their ancestors’ place from there. It’s all so traumatic,” Noshaba said.

Salve For Old Wounds

When Reena visited her ancestral house, its current occupants offeredher a room to stay the night. It turned out to be her own room from 75 years ago. She stood there alone in the middle of the night, touched every corner, sang the old songs of her teens, and cried again. “My home, the farms around there, the air and the trees, all continue to haunt me, as they are firmly etched in my memory,” she told TOI, quickly adding, “That visit was probably my last. ”

But Parag Sehgal, who is 41, might be able to visit his ancestors’ haveli again. Born and brought up in Chandigarh, Parag went numb when he scratched a dusty portion of the haveli’s outer wall last July. The palatial house in Lahore’s Model Town area is on the verge of collapse but fits his grandmother’s description perfectly. Even the plaque announcing ‘Sehgal Niwas’ is there.

“I cannot express my feelings. I could visualise my grandfather on a white horse – he was a tehsildar in those days. The horse stable is there. Noshaba arranged for our security and facilitated our travel to Kasur, Lahore and Gujranwala,” said Parag. GS Batra from Amritsar is also indebted to Noshaba. The 88-year-old returned from Pakistan last month. “It was a much-needed closure for me. For years, I dreamt of my old house in Tamman village, close to a gurdwara built along a natural spring. My life’s final wish has been fulfilled,” he said. “The gurdwara is gone and new buildings have come up. But I met the son of my father’s best friend Hayat Khan who became a Pakistan minister in the 1960s. He hosted lunch for me. Noshaba arranged everything. ” But for every Reena or Parag there are hundreds of others waiting for a chance to see their lost family homes in Pakistan. Anil Ghai and Praveen Kalra are among them.

At 70, Anil is a prosperous UP-based businessman in Najibabad town. He is also the president of Chakwal International, a group of Indian migrants from Chakwal (a district in Pakistan) and Noshaba’s town Talagang. Time is running out for a generation of displaced men and women, said Anil. “Most of the first-generation migrants with memories of undivided India are above 80. Getting visas is very difficult. Here, the government must step in before it’s too late. ”

Delhi-based Praveen, 68, whose family came from Sialkot, couldn’t stop talking about his great-grandfather. “He lived for over a hundred years and spent a considerable part of his life in Sialkot. I grew up in his lap listening to the rich tales of his home he so missed. I want to visit but getting a travel visa is not easy. ”

Noshaba said visiting Pakistan is easier for NRIs than resident Indians. “I’ve forgotten the number of people from India who connect with me on social media for a visa to visit ‘home’. They are in the twilight of their lives. . . Fond memories of their roots perhaps create a strong urge to visit, maybe for one final time. ”