Nutrition: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Statistics, year-wise

1993-2011: Changes

Dec 27 2014

India's eating habits may have changed, but not nutrition levels

Subodh Varma

In the past two decades, India's eating habits have changed but the nutritional level seems to be the same, a recent survey has found. Across the board, people are eating less cereals, replacing them with more fat and snacks, beverages and processed foods. Protein consumption has declined in rural areas and remained the same in urban areas. The average calorific val ue of food consumed was 2,099 kilocalories (Kcal) per person per day in rural areas and 2,058 Kcal in urban areas in 2011, according to the survey report released last week by the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO).This is less than the nutritional value in 1993-94, when a similar survey had found the levels at 2,153 in rural areas and 2,099 in urban areas.

The National Institute of Nutrition, ICMR, recommends 2,320 Kcal a day for a man aged 18-29 years, weighing 60kg and in a sedentary job. Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Gujarat have nutritional levels that are almost 10% lower than the national average for rural areas while UP, Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan have levels 10 to 20% higher, according to a National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) survey .

Another shocking aspect is the huge difference in nutritional intake of the poor and the rich. In rural India, a person belonging to the poorest 10% of population has a daily calorie intake of less than 1,724 Kcal, which includes 45g of protein with protein consumption at about 45g and 24g of fat. At the other end, a person from the richest 10% segment consumes more than 2,531 Kcal every day , almost 47% more than the poor person. A similar chasm can be seen in protein and fat consumption too.

In urban areas, this gap is worse. The poorest people get less than 1,679 Kcal per day while the richest get over 2,518 Kcal each -a difference of nearly 50%.

80% in rural India don't get required nutrition

Almost 80% of rural people and 70% of urban people are not getting the government-recommended 2,400 Kcal per day worth of nutrition, a situation that has very harmful health implications, apart from its sheer in humanity .

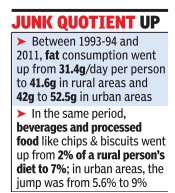

At the national level, daily protein consumption dipped from 60.2g for a person in 199394 to 56.5g in 2011-12 in rural areas and from 57.2g to 55.7g in urban areas. Oil and fat consumption increased from 31 to nearly 42g in rural areas and from 42 to 52.5g in urban areas.

The shares of items like fruits and vegetables, dairy products and egg, meat and fish was about 9% in 1993-94 which has marginally changed to about 9.6% in 2011-12.

The only food item that has seen a substantial jump in intake is classified as `other' in the survey and consists of various hot and cold beverages, processed food like chips, biscuits etc. and snacks. In 1993-94 these made up just 2% of a rural person's nutritional intake but rose to over 7% in 2011-12. In urban areas, this was 5.6% earlier and increased to about 9%.

The report also estimates that the survey would have counted food bought and prepared in a household but eaten by visitors or employees. If this is accounted for, calorific values get reduced by as much as 15-17% in rural areas and 5-6% in urban areas.

2004-19: better nourishment

Number of undernourished down by 60m in last 13 yrs, July 15, 2020: The Times of India

More Obese Adults, Less Stunted Kids In India Now, Says UN Report

United Nations:

The number of undernourished people in India has declined by 60 million, from 21.7%of the population in 2004-06 to 14% in 2017-19, according to a UN report.

The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World report said there were less stunted children but more obese adults in India.

The report — considered the most authoritative global study tracking progress towards ending hunger and malnutrition — said the number of undernourished people in India declined from 249.4 million in 2004-06 to 189.2 million in 2017–19.

The two subregions showing reductions in undernourishment, eastern and southern Asia, are dominated by the two largest economies of the continent — China and India.

“Despite very different conditions, histories and rates of progress, the reduction in hunger in both the countries stems from long-term economic growth, reduced inequality, and improved access to basic goods and services,” it said. The report is prepared jointly by the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), the United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef), the UN World Food Programme (WFP) and the World Health Organization (WHO).

It further said the prevalence of stunting in children under 5 years of age in India declined from 47.8% in 2012 to 34.7% in 2019 or from 62 million in 2012 to 40.3 million in 2019.

More Indian adults became obese between 2012-16, it said. The number of adults (18 years and older) who are obese grew from 25.2 million in 2012 to 34.3 million in 2016, from 3.1% to 3.9%. Across the planet, the report forecasts, that the Covid-19 pandemic could push over 130 million more people into chronic hunger by the end of 2020.

Nutrition, urban, 2017, state-wise

Afshan Yasmeen, October 6, 2017: The Hindu

Odisha tops in intake of greens, Kerala consumes the least; sweet consumption high in M.P., says study

A nation-wide study carried out by the National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau (NNMB) to assess urban nutrition shows not only a great diversity in food consumption in 16 States in the country, but also that Indians consume far less than the recommended quantum of several micro-nutrients and vital vitamins. Andaman and Nicobar Islands reported the highest intake of flesh foods, including meat and fish, Odisha has the highest consumption of green leafy vegetables (GLV). On an average, while the recommended dietary intake of GLV is 40g/CU/day, the consumption in the country is 24g/CU/day.

Madhya Pradesh has the lowest intake of flesh foods and Kerala consumes the least green leafy vegetables.

If Madhya Pradesh has a sweet tooth with the highest intake of sugar and jaggery, Odisha and Assam have the highest intake of salt. Rajasthan is high on the intake of fats and oils as well and milk and milk products.

The study, led by Avula Laxmaiah, Scientist (Director Grade) from National Institute of Nutrition (NIN), the country’s premier nutrition research institute, was released recently. The researchers used the method of a 24-hour dietary recall to collect food and nutrient information from 1.72 lakh people in 16 States.

While the average intake of cereals and millets was found to be 320g/CU/day, which is lower than the recommended dietary intake (RDI), the intake of pulses and legumes was about 42g/CU/day. This is on par with the suggested level of the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), said Dr. Laxmaiah.

States and Union Territories covered in the survey held in 2015-16: Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Assam, Bihar, New Delhi, Puducherry and Rajasthan.

‘Zero hunger’: state-wise map of India

Niti Aayog; June 11, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic, ' ‘Zero hunger’: a state-wise map of India, presumably as in 2016-17’

2009- 2024: Proteins, farm produce

July 2, 2025: The Times of India

From: July 2, 2025: The Times of India

From: July 2, 2025: The Times of India

New Delhi : Consumption of protein rich food in India has inched up in over a decade but fat intake has risen at a faster pace. Latest data showed cereals continue to be the most important source of protein among the five major food groups. The data released by the statistics office showed an increasing trend in daily intake of protein by individuals in urban as well as rural India since 2009-10 and trend was evident in most major states. Rajasthan, Haryana, Maharashtra and UP, however, showed a marginal decline in average protein intake. In urban areas, daily per capita intake of protein rose from 58.8 gms 2009-10 to 63.4 gms per day in 2023-24, an increase of 8%, while in rural areas, it rose at a slower pace, from 59.3 gms a day in 200910 to 61.8 gms in 2023-24. TNN

Egg, meat & fish consumption saw steepest rise

Pulses consumption in rural areas rose marginally, while it dipped in urban centres. In both areas, egg, meat and fish consumption saw the steepest rise. In the case of fat intake, there is an unmistakable rising trend, with every major state showing an increase, according to the Nutritional Intake report released by the statistics ministry based on the Household Consumption Expenditure survey of 202223 and 2023-24.

At the all-India level, the rise has been from 43.1 gms per person per day in 2009-10 for the rural population to 60.4 gms in 2023-24 and from 53.0 gms to 69.8 gms for the urban – a rise of more than 15 gms in both segments. All the major states show a rise in per capita per day intake of fat across rural and urban segments, the data showed.

The data showed that cereals accounted for 4647% of the share of protein in rural areas among the five major food groups, which include pulses, milk and milk products, eggs, meat and fish and other food category. In urban areas, it was about 39% for 2022-23 and 2023-24. The report showed that the contribution of cereals to protein intake has fallen by about 14% in rural India and nearly 12% in urban India from 2009-10. The fall in the share of cereals has been balanced by rise in the share of egg, fish and meat, other food and milk and milk products, the data showed.

Global Nutrition Report/ 2018

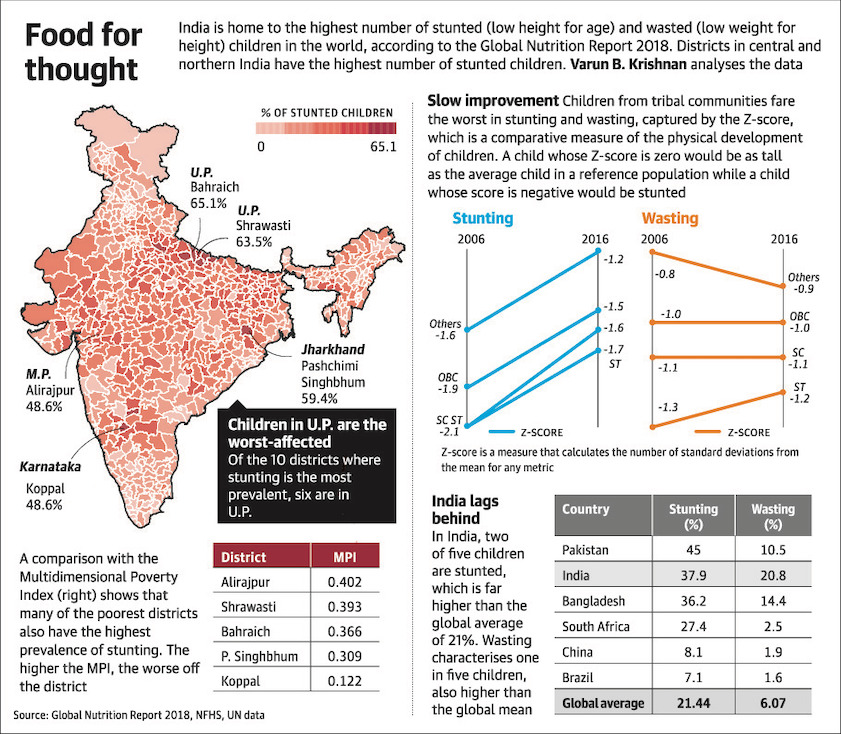

Child stunting and child wasting-2006,2016;

A comparison with the Multidimensional Poverty Index (right) shows that many of the poorest districts have the highest prevalence of stuntint. the higher the MPI, the worse off the district.

Source- Global Nutrition Report 2018, NFHS, UN data

From: December 7, 2018: The Hindu

See graphic:

% of stunted children;

Child stunting and child wasting-2006,2016;

A comparison with the Multidimensional Poverty Index (right) shows that many of the poorest districts have the highest prevalence of stuntint. the higher the MPI, the worse off the district.

Source- Global Nutrition Report 2018, NFHS, UN data

Calorie, protein intake

2009 – 2024

From: August 29, 2025: The Times of India

See graphic:

Daily per capita intake of calories and protein in India, urban and rural, 2009 – 2024

Dietary energy, sources

2014: sources of dietary energy

Apr 25 2015

The diet of a particular group of people is influenced by various factors including income, prices, personal and cultural preferences and geography. This also leads to different sources of dietary energy given the diverse dietary habits in different countries or regions. In India, about 60% of the dietary energy comes from cereals.Meat products contribute only 0.8% of the total energy, which is among the lowest in the world. In most Western countries, in contrast, cereals provide less than 30% of energy while more than 10% comes from meat products SOURCE: Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations Research: Atul Thakur ; Graphic: Asheeran Punjabi

Nutrition surveys in South Asia

Apr 05 2015

Rema Nagaraja

No nat'l nutrition survey in last 10 yrs

Neighbours Pak, Bangladesh & Nepal Have Been Holding Regular Audits

They may have lower growth rates than India, but Bangladesh, Pakistan and Nepal are more prompt about conducting regular surveys on the nutritional status of their population. The last nutrition survey done in India was ten years ago despite its unacceptably high levels of malnutrition. Neighbouring nations have each completed two surveys each during this period.

There has been no district level nutritional survey in India since 2002, more than 13 years back. National Statistical Commission chairman Pronab Sen when speaking at a round-table event on nutrition data said that there was “too little nutrition data“ for policy makers and the new National Family Health Survey (NFHS) data would be cru cial for rolling out new policy programmes to address malnutrition and other health issues.

“There is enough evidence to show a huge variance in the status of nutrition of children in tribal and nonaccessible areas in a state vis-à-vis urban areas. For any nutrition or health scheme to be planned and implemented, it is therefore essential to have the district level data. However, it is ironic that the `latest' government data for districts available is 13 years old (DLHS -2, 2002). It is appalling that the planning of our nutrition related schemes is being done primarily based on the state data, without taking into consideration the critical variance within the states with respect to the most affected and marginalized,“ said Komal Ganotra, director of policy, research and advocacy in the NGO CRY -Child Rights and You. The Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), a maternal and child nutritional programmes, is supposedly on a mission mode in almost 200 backward districts to address malnutrition. Districts are supposed to draw up a project implementation plan (PIP). But district ICDS officers are expected to draw up the PIP on the basis of 13-year-old data.

After NFHS 3 in 2005-06, the field work for NFHS-4 is currently on. After data collection there is the laborious and time-consuming process of checking data quality , verifying data, cross checking and then analysis. The data is not expected before the end of this year and district level data from it might not be available till well into 2016. The first round of NFHS survey took place in 1992-93, the second round in 1998-99 and the third round in 2005-6, after which there have been none.

Data from the Rapid Survey on Children (RSOC) carried out by Unicef and the women and child development (WCD) ministry in 2013 is yet to be made available.The data was sent to the health ministry for review about six months back by the WCD ministry , but nothing has moved since.

Even the district level household and facility survey (DLHS) in 2013 did not provide any district-level nu tritional data. Even if, as RSOC national level data suggests, stunting levels among children has fallen from 48% to 39%, it is still very high and probably masks much higher levels of undernutrition at state and district level.

Over two decades, close to 300 Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) have been carried out in more than 100 countries with the support of Unicef for generating data on key indicators on the well-being of children and women, and helping shape policies. However, India withdrew from MICS in 2000 after two rounds. This year the MICS programme completes 20 years of operation and five rounds of surveys. Bangladesh, Pakistan and Nepal are part of the MICS surveys. “Standard gap for carrying out such surveys is three to five years to enable taking stock and to do mid-course correction,“ said a public health expert.

Products: Nutrition Index

The Times of India, December 15, 2016

Indian Food Cos Far Short Of Providing Nutritional Qualities To Fight Malnutrition

The largest food and beverage manufacturers in the country need to pull up their socks when it comes to offering nutritious products to consumers. Research by the Netherlands-based The Access to Nutrition Foundation (ATNF) has found that food and beverage companies in India are falling far short of what they need to do to help fight malnutrition.

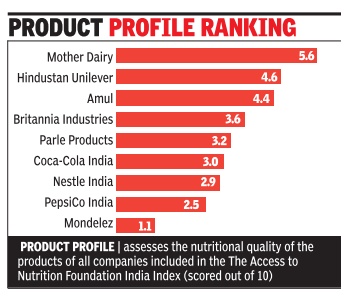

For instance, despite having the strongest nutrition and under nutrition-related commitments and policies, Nestle India, maker of Maggi noodles, scored the second lowest for nutrition qualities of its products among all the companies assessed under the India Access to Nutrition Spotlight Index. On the other hand, Mother Dairy scored the highest. “India faces the serious and escalating double burden of malnutrition, with a large undernourished population, as well as growing numbers of overweight and obese people who are developing chronic diseases,“ said Inge Kauer, executive director of ATNF. “Food and Beverage (F&B) manufacturers in India have the potential, and the responsibility, to be part of the solution to this double burden of malnutrition.“ Factor this: India is home to the largest number of stunted children in the world -48 million under the age of 5 -while at the same time, childhood obesity is reaching alarming proportions.The obesity prevalence rate reached 22% in children and adolescents aged between 519 years over the last five years, the report said.

Under the index, companies have been scored out of a maximum of ten in two ways -corporate profile and prod uct profile. While the former assesses companies' nutrition and undernutrition-related commitments and policies, practices and disclosure in seven areas of their business, the latter assesses the nutritional quality of the products of all companies included in the India Index.

The leading companies on the corporate profile -Nestle India and Hindustan Unilever -with scores of 7.1 and 6.7 respectively -have done more than the other seven companies assessed to integrate nutrition into their business models.

In the product profile segment, Mother Dairy , Hindustan Unilever and Amul, on the other hand, sell the largest proportion of healthy products among the Index companies. Mother Dairy scored 5.6 out of 10, Hindustan Unilever scored 4.6 and Amul scored 4.4.

World Bank Reports

Undernourished Children: A Call for Reform and Action , 2006

The Hindu Business Line, December 23, 2016

India, a rising star, is one of the few countries globally witnessing a steady GDP growth. Yet, while factors such as human capital, growing FDI, and initiatives to promote the country as a manufacturing destination are catalysing our development, there are some things with the potential to impede this growth.

One of the biggest challenges among those is malnutrition. Our vision of becoming a developed nation needs to be fuelled by a healthy population. However, we are on the brink of facing a malnutrition crisis.

It’s a crisis

A 2006 World Bank Report on India, Undernourished Children: A Call for Reform and Action , estimates the prevalence of underweight children in India to be among the highest in the world, and nearly double that of Sub-Saharan Africa.

Fifty per cent of Indian villages are severely affected by malnutrition. It is the single largest contributor to under-five mortality. Even if the children survive to adulthood, their brain development will be affected and they will suffer from a life-long elevated risk of infection.

The World Bank’s Nutrition at a Glance research report has put a figure to the crisis we are facing: annually, India loses over $12 billion in GDP to vitamin and mineral deficiencies.

This is a substantial amount. Yet if we scale up, core micronutrient interventions would cost less than $574 million per year.

How do we combat India’s malnutrition crisis? One important approach lies in food fortification. Fortification of staple foods such as milk, oil, sugar and flour has been globally recognised as an important strategy to eradicate malnutrition.

The key vitamins and minerals used for food fortification include iron, iodine, zinc, vitamin A, vitamin D, folic acid (B9), thiamin (B1), riboflavin (B2), niacin (B3), pyridoxine (B6) and cobalamin (B12). Among those vitamins and minerals, vitamin A, iodine and iron deficiencies create the greatest burden on public health and rank high on priority.

Other micronutrient deficiencies, such as riboflavin, folic acid, vitamin C and calcium, are also widespread. These deficiencies increase the risk of diseases such as goitre, blindness, anaemia and cognitive disorders.

Additionally, many country reports highlight the magnitude of malnutrition due to a family’s economic costs incurred and cultural links associated with micronutrient deficiencies.

Start with advocacy

As compared to other South Asian countries, India calls for advocacy programmes as a starting point for food fortification initiatives. While some non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and private organisations have been actively pursuing the food fortification programme with support from the Centre, the need of the hour is unique initiatives that will support a nourished lifestyle among the poor.

For example, in Rajasthan and Haryana, 80 per cent of the wheat consumed is processed in local mills. Some NGOs are collaborating directly with these local mills to ensure micronutrient fortification by providing vitamin A and vitamin D in flour.

Another successful initiative is providing vitamin A sachets to schoolchildren in municipal schools, as part of the midday meal programme.

Another approach is through public/private partnership which can help resolve the issue through unique business models. In the Philippines, 40 per cent of children between the ages of six months and six years had severe Vitamin A deficiency as of 2008, contributing to conditions such as night-blindness and Bitot’s spots.

The government started a nationwide food fortification program by enriching sugar with vitamin A, as sugar is the most widely consumed staple food in the nation.

They enlisted the support of the largest sugar manufacturer initially and then extended it to various food items such as fruit juices, noodles, margarine, canned tuna, etc.

They also promoted the importance of a balanced diet along with food fortification and vitamin A supplementation by creating a sustainable food fortification programme where stakeholders such as sugar manufacturers, the department of health, the Food and Nutrition Research Institute and the Unicef, came together to address the malnutrition issue.

Today, although the country has not yet eradicated malnutrition, less than 15 per cent of the children suffer from vitamin A deficiency.

It is, therefore, heartening to see that there are joint efforts already being taken to address this challenge, with national and global organisations joining hands.

Some States have taken a leaf from this initiative. Such programmes are under way on a small scale in certain States of India, but there is clearly a need to roll out such programmes nationwide.

Make it the law

For the children of the country to benefit from food fortification, centrally mandated laws are required.

We need a programme that is nationally scalable, such as the widely successful programme of salt fortification with iodine, which has significantly reduced goitre on a national basis.

We need to learn from our neighbouring countries such as Bangladesh and Pakistan. Bangladesh started a national wheat and oil fortification programme by adding vitamin A, iron, zinc, B1, B2, niacin, and folic acid nutrients across the country. Pakistan undertook a nationwide campaign to fight anaemia and vitamin A deficiency by undertaking wheat flour fortification with iron; edible oil/ghee with vitamin A and D; bio-fortification of wheat with iron and zinc; and zinc-fortified fertiliser.

This has been possible for both the countries due to measures taken and supported by their central governments.

In India, we are gradually taking some steps in the right direction, but we need to do very much more.

The Group of Secretaries on Education and Health — Universal Access and Quality has, among other things, identified fortification of food items like salt, edible oil, milk, wheat and rice with iron, folic acid, vitamin D and vitamin A, with a timeline of three years, as one of the measures to be undertaken to address the issue of malnutrition in the country.

See also

Nutrition: India