Pakistan History: Civilian Rule Restored (1988-1999)

Civilian Rule Restored (1988-1999)

This article is an extract from |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia is an archive. It neither agrees nor disagrees

with the contents of this article.

NOTE 2: The Pakistanis’ view of their history after 1947 and, more important, of the history of undivided India before that is quite different from how Indian scholars view the histories of these two periods. The readers who uploaded this page did so in order to give others Mr. Wynbrandt’s neutral insight into Pakistan’s history. Indpaedia’s own volunteers have not read the contents of this series of articles (just as it was not possible to read any of the countless other public domain books extracted on Indpaedia).

If you are aware of any facts contrary to what has been uploaded on Indpaedia could you please send them as messages to the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name (unless you prefer anonymity).

See also

Indpaedia has uploaded an extensive series of articles about the Pakistan Movement, published in Dawn over the years, and about the various Pakistani wars with India published in the popular media. By clicking the link Pakistan you will be able to see a list of these articles. The Pakistan Movement articles are presently under 'F' (for freedom movement).

Pakistan History: Civilian Rule Restored (1988-1999)

General Zia ul-Haq's unexpected death in 1988 brought about a return to civilian rule in Pakistan. Over the next decade a series of leaders struggled to establish firm control over the government. Two rivals came to dominate the political landscape during this period: Benazir Bhutto (1953-2007), daughter of the executed former prime minister, and Nawaz Sharif (b. 1949). Bhutto became the first woman to lead a modern Muslim nation. But her rule, as her father's had been, was marred by charges of corruption, and she was dismissed from office, only to rise once more as prime minister before suffering another tumble from power. Sharif, scion of one of Pakistan's wealthi- est families, whose power base was among the landless lower class, also lost and regained his office. Under his leadership the Pakistan Muslim League, the 1962 successor to the disbanded Muslim League, reemerged as a powerful political party. But political infighting again began to immobilize the machinery of state. Fearing another military takeover Sharif attempted to forestall a coup, but, instead, his efforts accelerated it. Once again Pakistan came under martial law and a general's rule, this time in the person of General Pervez Musharraf (b. 1943). Also during this period the still-unsettled Kashmir question again brought Pakistan and India to the brink of war, only this time the presence of nuclear weapons escalated the stakes in the standoff between the countries.

Benazir Bhutto's First Government

On August 17, 1988, Ghulam Ishaq Khan, former chairman of the Senate, succeeded General Zia ul-Haq and became interim president, as stipulated by the constitution. Ishaq Khan established an emergency council of advisers and directed general elections be held in November 1988. PREPARING FOR DESTINY

The following excerpts from Benazir Bhutto's 1989 autobiography, Daughter of Destiny, reveal Bhutto's hopes and fears during the final years of the Zia regime. As Pakistan moved toward elections scheduled for November 1988, a nervous Zia announced a new law that called for nonparty elections. The law was to have been imple- mented too late for the opposition to challenge it in court. But Zia and 30 others, including the U.S. ambassador to Pakistan and an American general, died in a plane crash while returning to Islamabad from a military base in eastern Pakistan.

I felt confidant as 1987 dawned. . . . [A]fter the long ban on political activities, we were building the PPP as a political institu- tion. Launching a membership drive, we enrolled a million mem- bers in four months, a remarkable figure for Pakistan, where the literacy rates are so low. We held party elections in the Punjab — an unheard of phenomenon in the subcontinent — in which over four hundred thousand members voted. We opened a dialogue with the opponents of the Muslim League in the Parliament and continued to highlight the human rights viola- tions of the regime. . . .

On May 29, 1988, General Zia abruptly dissolved Parliament, dismissed his own handpicked Prime Minister, and called for elections. I was at a meeting . . . with party members from Larkana when the startling message was passed to me. "You must be mistaken," I said to the party official who had sent me the note. "General Zia avoids elections. He doesn't hold them.

Regardless, the mood throughout the country was ebullient. Zia's own constitution called for elections within ninety days of the dissolution of the government, and to many it seemed that victory was within reach. . . . "No one can stop the PPP now," said one supporter after another. . . .

On June 15th, Zia announced the installation of Shariah, or Islamic law, as the supreme law of the land. . . . Many thought that the timing of Zia's latest exploitation of Islam was directed at me. The Urdu press was speculating that he could use the interpretation of the law by Islamic bigots to try to prevent me, a woman, from standing for election.

Source: Benazir Bhutto, Daughter of Destiny, New York and London: Simon and Schuster, 1989.

Benazir Bhutto, the daughter of former prime minister Zulfikar Bhutto, who had taken over the leadership of the Pakistan People's Party (PPP) after her father's execution in 1979, returned from exile when martial law was lifted in 1986.

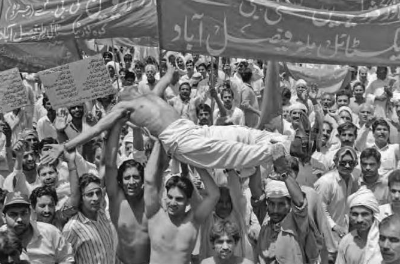

After a decade of authoritarian military rule, the return of a Bhutto to Pakistan's political landscape helped energize the democracy movement. Benazir Bhutto was born in Karachi and educated at Radcliffe College in the United States and Oxford University in England. She returned to Pakistan in June 1977 with the intention of entering the foreign service. Two weeks later General Zia ul-Haq staged his coup and arrested Prime Minister Zulfikar Bhutto. Benazir Bhutto spent the next 18 months in and out of house arrest. The execution of her father in 1979 served only to intensify her efforts to coordinate opposition to Zia's regime. In the summer of 1981 she was imprisoned for five months under solitary confinement in Sind. She was released in 1984 and went into exile in London. Her return to Pakistan in 1986 was greeted by a welcoming crowd of hundreds of thousands in Lahore. She began organizing the opposition and calling on Zia to resign and hold national elections.

Had Zia not perished it is possible that the elections he had sched- uled would have been canceled or the state apparatus would have been marshaled to ensure his electoral victory. But without him the 1988 election campaign proceeded as planned. The PPP remained unaligned and independent of other political parties. In the November elections the PPP won a majority in Sind, but no party gained a majority in any other province. Nonetheless, the PPP was the only party to have a significant following in all four provinces. Moreover, it was the largest party in the National Assembly, with 94 seats, one of them occupied by newly elected Benazir Bhutto.

Under the Revival of the Constitution of 1973 Order enacted by Zia, the president could appoint any member of the National Assembly as prime minister. With the backing of both the PPP and the Islami Jamhuri Itehad (IJI, or Islamic Democratic Alliance), a coalition of nine parties formed that year to oppose the PPP in elections, Ghulam Ishaq Khan won the legislative election for president on December 13, 1988. Following tradi- tion as well as privilege, Ishaq Khan chose Benazir Bhutto, leader of the dominant party, to form a new government and serve as prime minister.

In order to form a government, Bhutto had to jettison the PPP's non- aligned stance and forge a coalition with the Muhajir Qaumi Mahaz (MQM, or Muhajir National Movement), which represented the muha- jir (refugees from India following partition) community and several other parties. The MQM agreed to back the PPP at both the national

and the provincial assemblies. Both parties pledged equal protection to all people of Sind, important to the muhajirs as they often felt discrimi- nated against by native Sindis.

In her first address to the nation as prime minister, Bhutto presented her vision of a Pakistan that was forward-thinking and democratic but guided by Islamic principles. She announced the release of political pris- oners, restoration of press freedoms, and the implementation of stalled educational and healthcare reforms. The ban on student unions and trade unions was lifted. She promised increased provincial autonomy, greater rights for women, and better relations with the United States, Russia, and China. Improved relations with India were pursued in December 1988 at the fourth SAARC Summit Conference, where the path was cleared for the acceptance of three peace agreements between Pakistan and India.

Bhutto's Foreign Policy

The end of the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, which occurred in the last days of Zia's rule, signaled a change in Pakistan's foreign relations. The Geneva Accords, which ended the war, were signed in April 1988, and the following month Soviet forces began their withdrawal. Border skirmishes continued as mujahideen attacks went on, some staged from Pakistan. But Pakistan had lost its strategic importance in the cold war. Without the cold war, whose end was marked by the collapse of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, the economic and military blandish- ments both sides had offered Pakistan and other emerging countries had come to an end.

Benazir Bhutto had been a persistent critic of Zia's alliance with the United States and had denounced him for allowing Pakistan to be used as a base for the mujahideen. But after taking office, she attempted to strengthen the country's alliance with the United States. Like her father, Benazir Bhutto was an indefatigable traveler, making frequent trips to meet with heads of state around the world. In June 1989 Bhutto visited the United States to allay fears of Pakistan's nuclear capabilities. She told the administration that Pakistan had no nuclear weapons, but defended her nation's right to pursue its nuclear program. In an address to a joint session of Congress she proclaimed Pakistan's willingness to make a pact with India declaring the subcontinent a nuclear-free zone. Bhutto tried to ease tensions with India while seeking solutions to the disputes — primarily Kashmir — that had bedeviled relations since the birth of the two nations. In 1989 Rajiv Gandhi (r. 1984-89), India's prime minister, visited Bhutto in Islamabad. In talks Bhutto reiterated Pakistan's willingness to make the region a nuclear-free zone, a pro- posal Gandhi declined to consider.

Bhutto succeeded in gaining readmission to the Commonwealth in 1989, making Pakistan eligible for trading privileges with other domin- ions, which the country desperately needed. Previous efforts to rejoin had been blocked by India on the grounds that Pakistan was not a democracy, as it was under military rule. With a civilian again in charge of the nation, that objection was voided.

Bhutto's Domestic Policy

Bhutto championed a Western secularist, socialist agenda, eschewing the pro-Islamic policies of the Zia regime. Women's social and health issues were staples of her campaigns. However, her stated policies were rarely translated into action. No legislation to improve welfare services for women was proposed. Campaign promises to repeal Hudood and Zina ordinances, which called for punishments such as amputations for theft and stoning for adultery, went unfulfilled. To be sure, Bhutto faced significant obstacles in advancing any legislative agenda. Much of the decision making remained in the hands of the military and the intelligence agencies, where Zia had placed it. Bhutto was reluc- tant to challenge these powers, since the military had time and again demonstrated readiness to take over the government when threatened. Perhaps she was fearful as well — the army, after all, was the institution responsible for the execution of her father.

She had also inherited many political enemies of her father's, and Pakistani politics remained as focused on personal power and games- manship as on advancing the national interest. A major PPP adversary was Nawaz Sharif, leader of the PML and chief minister of Punjab, the most populous province. The PML and PPP were natural enemies; PPP founder Zulfikar Bhutto had nationalized industries to break the power of Pakistan's wealthiest families, and one of those families was Nawaz Sharif's. Moreover, Nawaz Sharif was a protege of Zia, the military ruler who had Zulfikar Bhutto hanged. Benazir Bhutto spent an inor- dinate amount of time and effort trying to oust Nawaz Sharif from his post in the Punjab. Another problem Bhutto faced was in the person of President Ghulam Ishaq Khan, with whom she clashed repeatedly, especially over military and judicial appointments.

Just as significant, Bhutto was unable to parlay the electoral success of the PPP coalition and her own popularity into creating a cohesive domestic policy for Pakistan. Bhutto's alliance with the MQM, while put- ting the PPP over the top in the national elections, proved an obstacle when it came to parliamentary action. Furthermore, her alliance with the rival political bloc weakened her credibility within the PPP (though it never threatened her leadership of the party), especially among the Sindi nationalists who had been among her strongest supporters. One of Bhutto's notable shortcomings during this and her second administration as prime minister was her failure to follow through on her announced campaign initiatives to improve women's health care and other social issues concerning women. In fact, "the PPP government's performance was lacklustre, with not a single new piece of legislation being passed or even introduced, apart from two annual budgets" (Jacques 2000, 170).

Another, but no less important, domestic issue where Bhutto floun- dered regarded Islam. Like her father, Benazir Bhutto was a secular- ist who, as an opposition leader, had denounced Zia's move toward Islamization of Pakistan. As prime minister she altered this stance for political expediency but discovered that other groups and leaders were farther ahead than she was in this approach. Nevertheless, her hard-line stance in early 1990 regarding the ongoing Kashmir dispute with India gained her credibility with the religious party Jamaat-i-Islami. Despite these problems Bhutto's first term as prime minister was not completely ineffectual. During her 20 months in power, she ended a ban on unions in Pakistan and, as part of her program to modernize Pakistan, she pushed for rural electrification. She also attempted to encourage private investment in the Pakistani economy.

However, her efforts were hampered by the ethnic violence that pervaded Sind and would ultimately cause the MQM to remove itself from the ruling coalition, paralyzing Pakistan's Parliament and further destabilizing Bhutto's domestic program.

The Political Landscape of Sind

Following partition in 1947 Urdu-speaking Muslims from India, called muhajir, "migrant," in Urdu, settled in Sind's urban centers of Karachi, Hyderabad, and Sukkar. Concurrently, many Hindus left for India. The shift profoundly changed the dynamics of Sind's economy and politics. Muhajirs were generally nationalists, believing in the ideal of a united Islamic country, and opposed ethnic identification. Primarily middle class and better educated than native-born Pakistanis, muhajirs came to dominate the Civil Service of Pakistan (CSP) and formed a powerful administrative class. With muhajir support, efforts were made to adopt Urdu as Pakistan's national language as a way to unify the country and forge a national identity. But Sindis, whose language is called Sindi, felt their culture threatened, and when Urdu was made a compulsory sub- ject in primary schools in 1962, Sindis called a strike in response, one of the first large-scale manifestations of Sindi-muhajir conflict.

During Ayub Khan's reign the Punjabi-Pashtun-dominated military took increasing charge of the state bureaucracy, reducing muhajir con- trol over the CSP. The move of the capital from Karachi, the center of muhajir power, to Islamabad also diminished the emigres' influence.

Sindis saw Zulfikar Bhutto, scion of a Sindi family of feudal land- owners, as empowering Sindi nationalism and were core PPP support- ers. The muhajir, on the other hand, rightly viewed Zulfikar Bhutto as an adversary. He made the study of Sindi compulsory in school, provoking language riots in 1972 as Sindi and muhajirs battled over the compulsory instruction. In the 1973 constitution Bhutto also introduced a quota system reserving 1.4 percent of posts in the central administration for rural Sindis. At the time, muhajirs held 35.5 percent of the civil service posts, although they constituted only 8 percent of the population. Bhutto also instituted a quota policy mandating that 60 percent of state jobs be reserved for rural residents and 40 percent for

urban residents and a similar quota for admissions to state-owned uni- versities. These quotas were enacted to improve the lot of rural popula- tions, which represented the majority of Sindis. Bhutto also reformed the CSP, further reducing muhajir power. More language riots erupted in 1972 after the Sind assembly made Sindi the province's official lan- guage, while Urdu was adopted as the official language in Baluchistan, NWFP, and Punjab.

In 1978 growing feelings of muhajir disenfranchisement led Altaf Hussain (b. 1963) to form the All Pakistan Muhajir Student Organization (APMSO). The group quickly won converts from Islami Jamiat-e-Talaba (UT), the student wing of Jamaat-i-Islami, making the muhajir move- ment an adversary of the UT from its inception. The two groups clashed on college campuses in the early 1980s during Zia's rule. Following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, Pashtun refugees settled in Karachi. Many went into transportation and moneylending businesses and into housing, a market previously controlled by Punjabis and muh- ajir s, leading to tensions between Pashtuns and their muhajir tenants. In the mid-1980s Pashtun-owned minibuses, called the yellow devils, were causing an average of two deaths per day. In 1985 a Pashtun bus driver in Karachi ran a red light and plowed into a group of students from Sir Syed College. The accident triggered a protest by muhajir stu- dent activists, which was joined by muhajir renters and soon erupted into pitched battles called the transportation riots, between muhajirs and Pashtuns. In their aftermath, the Pashtuns formed an alliance with the Punjabis, with whom they already had dealings through their arms trade with the Punjabi-dominated military.

Muhajir ethnic consciousness overcame its nationalist impulses in 1984 with the rise of the Muhajir Qaumi Movement (MQM), now officially known as Muttahida Qaumi Movement, or United National Movement, which had its origin in APMSO. MQM quickly gained power in the urban centers of Sind, winning the mayorships of Karachi and Hyderabad in 1988. Government efforts to weaken the party led to its splintering into two factions: the main party, MQM (A), led by Altaf Hussain, and an offshoot, the MQM(H), for Haqiqi (or "truth") faction, which appealed to religious fundamentalists and was under the influence of the Pakistani government. Fighting between the two factions and with police and security agencies has claimed many lives in Karachi.

In the 1988 elections the MQM allied with the PPP, now headed by Benazir Bhutto, and emerged as the third-largest party in the National Assembly. To win their support, Bhutto had pledged to protect and safe- guard the interests of all the people of Sind, regardless of language, reli- gion, or origin of birth, as well as to stamp out violence and to support the rule of law. But tensions between the Sindis, the PPP's traditional base, and MQM supporters continued. In October 1988 hundreds of Sindis were killed during a protest in Hyderabad, for which the muha- jir were blamed, triggering ethnic riots between the communities. In August 1989 MQM officially ended its alliance with the PPP, claiming the ruling party had failed to live up to its agreements. From May of that year to the following June, hundreds more died in ethnic violence between the two groups.

President Ishaq Khan Dissolves the Government

Bhutto was eager to reinstate the constitution of 1973, voiding the 1985 Zia amendments that allowed the president to dismiss the government and dissolve legislative assemblies, and to return the country to a parlia- mentary form of government. It would also assure she could not be dis- missed from office. Failing to gain sufficient support, she soon dropped the effort. On August 6, 1990, President Ghulam Ishaq Khan, invok- ing the Eighth Amendment of 1985 and Article 58 2(b), dismissed the Bhutto government, alleging corruption and incompetence; dissolved the National Assembly; and declared a state of emergency. One of the nation's best-known journalists wrote at the time, "The scenario presented has become depressingly familiar — like repeat performances of a B grade movie. A well-rehearsed procedure is carried out, even the words used by the person in high authority to justify his action are paraphrases of what has been heard before, including the charges of corruption and ineptness leveled against the targeted incumbents ..." (Khan 1998, 466).

Ghulam Mustafa Jatoi, leader of the Combined Opposition Parties, a second coalition party opposed to the PPP, was named caretaker prime minister (r. Aug.-Nov 1990) after the dismissal of Benazir Bhutto's government. A native of Sind and one of Pakistan's largest landowners, Jatoi had been a PPP veteran and was in the first cabinet of Benazir Bhutto's father. But he was removed as head of the PPP in Sind upon Benazir Bhutto's return in 1986 and left the party. The partisanship behind selecting a member of the opposition rather than a member from the leading party magnified the sting of Ishaq Khan's action. Ishaq Khan soon dissolved the provincial assemblies as well and scheduled new elections for October 1990. Benazir Bhutto's husband, Asif Ali Zardari (b. 1956), was arrested on charges of blackmail and imprisoned for more than two years.

Mustafa Jatoi was also in charge of the accountability proceed- ings aimed at investigating and bringing to justice members of the national government accused of corruption and malfeasance. Bhutto was charged and testified before the accountability tribunals, but she remained free to conduct her political activities.

1990 Elections

Nawaz Sharif campaigned on a platform of conservative government and ending corruption. The elections for national and provincial assemblies were held on October 24 and 27, respectively. The caretaker government, chosen for its partisanship, took an active role in assist- ing the Islamic Democratic Alliance (IJI) in winning the elections. His Pakistan Muslim League (PML) had the backing of the IJI as well as the MQM. Evidence exists that the ISI, the state intelligence agency, engineered the IJI's initial support for Sharif during the 1990 election. During his second term as prime minister he was to lose the support of the IJI after he took a more secular course during his second term as prime minister. Despite widespread complaints of election irregulari- ties, outside observers declared the 1990 election generally fair. More than 40 deaths were linked to election violence.

About 45 percent of the 47 million registered voters cast ballots. In the National Assembly 217 seats, 10 of which were held by non-Muslims and 20 of which were reserved for women, were to be chosen by the elected members. The principal parties were the Pakistan Democratic Alliance (PDA), dominated by the PPP, and the IJI, dominated by the PML. The PDA campaigned on the issue of the illegal dismissal of the government. The IJI stressed the incompetence of the Bhutto government as well as the corruption charges against it. The IJI trounced the PPP-led alliance, taking 105 seats to the PDAs 45 seats. The MQM won 15 seats, while the Awami National Party (ANP) and Assembly of Islamic Clergy QUI) split a dozen seats between them. Independents and others took 30 seats.

Benazir Bhutto continued her opposition efforts during Sharif's rule, including attempts to mount large-scale antigovernment protests. In 1992 Sharif banned her from the nation's capital and had her confined to Karachi though she was not placed under house arrest.

Nawaz Sharif's First Government

On November 1, 1990, Mian Muhammad Nawaz Sharif, finance min- ister under General Zia and chief minister of Punjab under Bhutto,

became prime minister for the first time (r. 1990-93, 1997-99). He was a native of Lahore and scion of one of Pakistan's most prominent families.

In his first address to the nation he promised a comprehensive national reconstruction program and to increase the pace of industri- alization. His leadership, after that of Bhutto and Jatoi, whose families were rooted in the rural aristocracy, represented the ascending impor- tance and power of the industrial class. Identifying unemployment as the nation's primary problem, Nawaz Sharif saw industrialization as the cure.

Nawaz Sharif was a political moderate, but he was also a religious conservative and a Zia protege, comfortable returning the country to a more Islamic course. And from a political and pragmatic perspec- tive, his coalition included the Islamist JUI party, whose support was needed to maintain the coalition. Sharif's backing for a conservative religious agenda would cement their allegiance. In May 1991 his gov- ernment passed the Shariat Bill — the bill that Zia had tried but failed to push through the National Assembly in 1985 — which made the Qur'an and the Sunna the law of the land provided that "the present political system . . . and the existing system of Government, shall not be challenged" and provided that "the right of the non-Muslims guaranteed by or under the Constitution" shall not be infringed upon (Enforcement of Shari'ah Act, 1991, Act X of 1991, Section 3). The act was unpopu- lar with both secularists and fundamentalists, the former fearing that Pakistan was becoming a theocracy, the latter angry that the law did not go far enough. Although a government group whose task it was to assist Islamization recommended several immediate steps, the act was never enforced. For example, in November 1991 the nation's supreme religious court, the Federal Shariat Court, declared a score of federal and provincial laws repugnant to Islam and therefore void, including one pertaining to the payment of interest. However, bans on interest on all loans would have been an impediment to Nawaz Sharif's industrializa- tion plans. The ruling was appealed and never implemented.

Sharif's Economic Policy

A conservative industrialist whose family "owned the biggest industrial empire in the country" (Bennett Jones 2002, 231), Sharif supported an economic policy focused on restoring to the private sector indus- tries that had been nationalized by Zulfikar Bhutto. This was as much personal as it was domestic policy to increase tax revenue: In 1972 Zulfikar Bhutto had nationalized the Sharif family's Ittefaq Foundary (The company was denationalized in 1979, around the time Nawaz Sharif was beginning his political career.) Sharif also went farther than Benazir Bhutto in enticing foreign investment by opening Pakistan's stock market to foreign capital, and foreign exchange restrictions were loosened during this time. (However, in his second government Sharif inexplicably reversed this trend when he voided contracts signed between foreign power companies and the Bhutto government.) Having no ties to the landowning aristocracy, Sharif also undertook targeted land reform efforts in Sind, where land was distributed to the poor. He also "had a penchant for costly projects of questionable economic value" (Kux 2001, 44). Large development projects, such as the Ghazi Barotha Hydro Power Project on the Indus River in Punjab, the Gwadar Miniport in Baluchistan, and, in his second government, a superhigh- way connecting Lahore and Islamabad, were commissioned. Perhaps Sharif's most controversial economic program involved the distribution of "tens of thousands of taxis" to towns and villages. Technically, the government subsidized the purchase of the imported taxis by young men with the agreement that these "loans" would be repaid, but well into the Musharraf regime few of the loans had been paid off. Sharif's economic policies placed him in good standing with the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The latter especially played a role in Pakistan's economic life during the 1990s, as the country under changing leadership, struggled to remain sol- vent. However, IMF assistance was contingent upon debt reduction by Pakistan. Pakistan's national debt impeded Sharif's economic policies, and this was compounded by the suspension of the United States's military and economic assistance program (in response to Pakistan's nuclear- weapons program), and the end of the Soviet-Afghan War. Because of the fear of a Soviet threat on its border, Pakistan was able to garner foreign aid amounting to as much as 2.7 percent of its gross national product, equal to $10 per capita in 1990. Within seven years the per capita amount had fallen to half that amount (Kux, 2001, 44). Exacerbating Pakistan's dire economic situation during this time was a decline in worker remittances from the Persian Gulf.

The damage to the economy done by the unpaid taxi loans actually paled in comparison to the unpaid loans of various Pakistani politi- cians, including Sharif himself. These unpaid loans contributed to the destabilization of Pakistan's banking system so that by the late 1990s it was on the verge of collapse.

Foreign Policy and Kalashnikov Culture

In foreign affairs Nawaz Sharif strengthened relations with Central Asia's Muslim republics that had formed in the wake of the Soviet Union's col- lapse in 1991. Pakistan also joined the international coalition to drive Iraq out of Kuwait during the Gulf War (1990-91), although the largest religious party in the IJI coalition, the Jamaat-i-Islami (JI, or Islamic Assembly), opposed the policy, as a defeat of Iraq would strengthen the Shi'i regime in Iran.

Across the border to the west, Afghanistan was disintegrating into chaos. After the Soviet withdrawal in 1989 and the fall of the Communist government in 1992, warring factions carved the nation into fiefdoms, and law and order broke down. Nawaz Sharif attempted to broker a peace among the competing factions with the Islamabad Accord, negotiated under his direction, but the violence continued. The lawlessness spread into Pakistan. Fueled by ethnic and political rivalries and easy access to weapons, crime and terrorism in the country grew rampant. Pakistanis labeled this outbreak of violence "the Kalashnikov culture," after the ubiquitous Soviet-made automatic weapon that made the carnage possible.

Bank Of Credit And Commerce International (Bcci)

Prime Minister Zulfikar Bhutto nationalized Pakistan's privately owned banks in 1974. However, foreign banks could still oper- ate in the country. One of the most important was BCCI, the Bank of Credit and Commerce International. Though chartered in Luxembourg, BCCI had three major branches in Pakistan and was founded by a well-connected Pakistani banker, Agha Hasan Abedi (1922-95). Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif's family business was a major borrower. In 1991, the year that banking was opened to Pakistan's private sector under the government's economic liberalization pro- gram, the BCCI collapsed in what was called the biggest bank fraud in history, estimated to have involved losses of between $10 billion and $17 billion. A U.S. Senate report completed in 1992 concluded BCCI was "a fundamentally corrupt criminal enterprise" (Kerry and Brown, 1992, I). In addition to fraud, money laundering, and bribery, the report also charged the bank with "support of terrorism, arms trafficking, and the sale of nuclear technologies; management of pros- titution; the commission and facilitation of income tax evasion, smug- gling, and illegal immigration; illicit purchases of banks and real estate; and a panoply of financial crimes limited only by the imagination of its officers and customers" (ibid., I). The Pakistani branches were con- duits for significant parts of these activities. BCCI received additional attention in the United States for two reasons: The bank was found to have secretly acquired 25 percent ownership of a large U.S. bank, First American, without regulatory approval, violating U.S. law; and it was found that the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) had been aware for several years of BCCI's activities, but had not informed other agen- cies, prompting speculation that the spy agency itself may have been among those taking advantage of the bank's lax controls and illegal practices. Most of the financial losses had mundane roots: poor busi- ness practices and bad lending decisions. In the years since, most lost funds were recovered through forfeitures, fines, and settlements.

The roots of the violence lay in the cultural heritage of the Pashtun, for whom carrying a gun has long been a tradition born of necessity Defense of tribal lands, banditry blood feuds, and pursuit of badal, or revenge, all required firearms. The availability of weapons increased dramatically in the aftermath of the Soviet invasion. Black market Soviet weapons and guns intended for the mujahideen swept into Pakistan. So did heroin. Afghan warlords, who managed the fight against the Soviets, financed arms purchases in part by the trafficking of heroin, refined from Afghanistan's abundant opium crop at hundreds of small labs. A culture of smuggling and drug trafficking grew. Arms were also needed to protect the heroin.

The Pakistani towns of Sakhkot, which had a gun market boasting more than 200 gun dealers, and Darra Adam Khel, 25 miles south of Sakhkot, where townspeople craft working imitations of almost any handgun or rifle, became symbols of the Kalashnikov culture.

Pakistan had virtually no drug culture prior to the Afghan war. The number of heroin addicts went from fewer than 10,000 to 12,000 in 1979 to more than 500,000 by the mid-1980s and as many as 3 million to 4 million by 1999. Many refugees from the war resettled in urban areas of Pakistan, particularly in Karachi. The cycle of guns, addic- tion, and violence took root here too. By the late 1980s, Karachi and Hyderabad were being compared to Beirut for their level of violence.

Adding to the problem of violence is the police force, whose members are typically regarded as corrupt and ineffective. Those who want justice seem compelled to seek it for themselves, and taking the law into one's own hands rarely carries consequences from law enforcement agencies.

In an effort to stem the chaos the Sharif government ordered citi- zens to turn in weapons, with little success. To deal quickly with those sowing the mayhem the legislature passed the Twelfth Amendment, which allowed for the quick establishment of trial courts to dispense summary justice.

Pakistan's legislative bodies mirrored the chaos. Dissension grew rife in the IJI coalition, particularly within the Pakistan Muslim League, the IJI's largest party. The right-of-center and religious parties compris- ing the coalition had been united in their opposition to the PPP, but with their primary adversary defeated, their unity splintered. Relations between Nawaz Sharif and President Ishaq Khan were also souring. In 1993 the prime minister and president began trying to oust each other through behind-the-scenes maneuvering.

As he had once before, on April 19, 1993, President Ishaq Kahn invoked the Eighth Amendment, dismissed Nawaz Sharif and his gov- ernment for corruption, and dissolved the National Assembly. Ishaq Khan named Balakh Sher Khan Mazari (r. April-May 1993), head of a clan of landowners, as the caretaker prime minister. General elections were scheduled for July 1993. However, in May the Supreme Court overturned the presidential order ousting the government, and Nawaz

Law Enforcement

The basic structure of Pakistan's police force was defined in Article 23 of the Indian Police Act of 1861. The police were responsible for preventing crime and detecting and arresting criminals, executing orders and warrants, and gathering and reporting informa- tion concerning public order. Other than revisions to the act dating from 1888 and the adoption of the Police Rules of 1934, the document still defines the role of Pakistan's police. The mission or approach changed little after partition. Each of the four provinces has its own police force, and traditionally there has been little integration of their operations. The senior positions are staffed by members of the Police Service of Pakistan, an organization similar to the Civil Service of Pakistan. Members are relatively well paid and have a greater degree of power than other civil servants; therefore, it is often the first choice of high-ranking students seeking entry to government service. Each provincial force is headed by an inspector general, aided by a deputy inspector general and an assistant inspector general. They oversee the work of a division, or range, which coordinates police activity within areas of each province. Most police work is conducted at the district level, under the direction of a superintendent, and at the subdistrict level, headed by an assistant or deputy superintendent. The great majority of police personnel are assigned to subdistrict stations. The lowest rank is constable, then, in ascending order, head constable, assistant subinspector, subinspector, sergeant, and inspec- tor. Larger cities have their own police forces, but these are under the direction of the provincial police forces. Police in Pakistan are gener- ally unarmed. They frequently use a lathi, a five-foot wooden staff, for crowd control, used to hold back throngs or as a club. Traditionally provincial police were almost exclusively male. Under Benazir Bhutto women were inducted into the police force as part of a campaign for equal rights for women.

Sharif was reinstated as prime minister. He and the president remained at odds, bringing the government to a standstill.

Benazir Bhutto's Second Government

In July 1993, after two weeks of negotiations, both Nawaz Sharif and Ishaq Khan resigned their positions, and the national and provincial assemblies were dissolved once again. Moeenuddin Ahmad Qureshi (r. July-Oct. 1993), a senior World Bank official, was named caretaker prime minister, and Wasim Sajjad (r. July-Nov. 1993), Senate chair- man, the caretaker president. Though he served only a few months, Moeenuddin Qureshi undertook important reforms. Without concern that he would be voted out of office, he made tough decisions that would have been difficult for an ambitious politician. Qureshi devalued the currency, cut farm subsidies, slashed public sector expenditures, and eliminated 15 ministries. He also raised the prices of critical items, including wheat, gasoline, and electricity. Qureshi also published the names of individuals with unpaid loans from state banks totaling some $2 billion; the list included many prominent politicians. Those who failed to repay their debts were barred from running for office in the upcoming October 1993 elections.

Bhutto's Return

New national and provincial elections were held October 6-7, 1993. The PPP campaigned on the platform of an "Agenda for Change," focused on improvements of social services. The MQM boycotted the election. Turnout was low, with only about 40 percent of those eligible voting. The Pakistan Muslim League (PML) led by Nawaz Sharif won 72 seats. The PPP won a plurality, with 86 seats in the National Assembly, but failed to win a majority. Yet the party did well in all four provinces. Bhutto, through a coalition with minor parties and independents, achieved a majority, earning the right to form a new government. In November, the national and provincial assemblies elected as president Farooq Ahmed Khan Leghari (r. 1993-97), a young PPP party loyalist. Hailing from a family of hereditary chiefs of the prominent Leghari tribe, Leghari began his career in the civil service after earning a degree from England's Oxford University. His service as government appointee and elected official was interrupted by four years in prison during the martial-law years after 1983. In his first address as president, Leghari pledged to revoke the Eighth Amendment, which had previously been used to dissolve govern- ments at presidential whim. He also supported weakening the power of religious courts and expanding women's rights. With the prime minister and president from the same party, many hoped the continual warring between these offices would end. But Leghari was soon embroiled in scandal and controversy, dooming his push for reforms.

Bhutto and the opposition, particularly the MQM, continued to be at loggerheads. In the fall of 1994 Nawaz Sharif embarked on a "train march," traveling by rail from Karachi to Peshawar to dramatize their opposition to the Bhutto government. The "march" drew massive crowds along the route in a display of the agitational and confronta- tional tactics that characterized both Pakistani politics and these two bitter rivals. In September a general strike was declared, and Nawaz Sharif called for another demonstration of resistance in October. Bhutto arrested several opposition leaders who took part in the protests, draw- ing widespread condemnation.

Relationship with the United States

Throughout the late 1980s Pakistani officials made statements indicat- ing the country had achieved a nuclear capability, as intelligence reports continued to describe advances in its weapons program. Since 1990 the United States had been withholding delivery of 28 F-16 fighter jets Pakistan had ordered — and paid for at a cost of $1.2 billion — under the terms of the Pressler Amendment, enacted by the U.S. Congress in 1985. The amendment required that before the president could authorize foreign aid to Pakistan, he had to certify that the country was not developing and did not possess nuclear weapons. President Ronald Reagan had waived the requirement, as allowed by the law, in 1988, when Pakistan's assistance in the U.S. fight against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan seemed crucial. However, the Soviets had withdrawn in 1989, and in 1990 President George H. W. Bush (r. 1989-93) did not certify Pakistan as a nuclear-free nation, thereby triggering an aid embargo. At the time, Pakistan was the third largest recipient of U.S. military assistance — after Israel and Egypt. In 1986 the United States and Pakistan had agreed on a $4 billion economic devel- opment and security assistance program that Pakistan would receive, paid out from 1988 to 1993. Pakistan was in the midst of an ambitious program to refurbish its armed forces, looking across the border at its bigger, nuclear-armed enemy, India. In addition to depriving Pakistan of material it needed to have a credible defensive force, the Pressler Amendment targeted only Pakistan, though other nations were known to have nuclear weapons programs that violated the terms of the UN nuclear nonproliferation treaty. Moreover, India had started the nuclear arms race and had escaped all penalties of the Symington and Pressler amendments. Relations between Pakistan and the United States deterio- rated sharply from 1990 through 1993, as issues of weapons develop- ment, terrorism, and narcotics caused a growing rift between Islamabad and Washington. In 1992 the United States almost declared Pakistan a state sponsor of terrorism, primarily due to its support for Kashmiri militants. In the summer of 1993 the United States placed more sanc- tions on Pakistan, charging it with receiving prohibited missile technol- ogy from China.

In late 1993 U.S. president Bill Clinton (r. 1993-2001) proposed revising the Pressler Amendment, citing the unequal treatment of Pakistan and India over their respective nuclear programs. But Clinton faced strong objections from legislators and withdrew his proposal in early 1994. A few months later his administration pro- posed a one-time sale of F16s, contingent upon Pakistan pledging to cap the production of weapons-grade uranium. This proposal paral- leled a liberalization of Pakistan's economy to a more market-based system, which the United States was eager to encourage. In January 1995, the thawing relationship between the two nations was under- scored by a visit to Pakistan by U.S. defense secretary William Perry (r. 1994-97). Following the visit, Perry proclaimed that the Pressler Amendment had failed in its objective to halt Pakistan's nuclear program and had actually been counterproductive. Benazir Bhutto traveled to Washington, D.C., in April, and in early 1996 the Brown Amendment was passed, which removed nonmilitary aid from the purview of the Pressler Amendment and gave the president a onetime waiver to permit the release of the military equipment embargoed since 1990. President Clinton authorized the release of some $368 million in military equipment. Though the F-16s were not among the approved items, Clinton pledged to reimburse Pakistan for the money it had already paid for the jets. Meanwhile, Pakistan continued to make progress in its nuclear program.

A visit to Pakistan by First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton and her daughter, Chelsea, in 1995 helped project to the world an image of Pakistan as a modern, progressive country. Bhutto's visit to the United States the previous year had already helped raise the country's visibility. International investment in Pakistan increased.

Bhutto's Central Asia Policy

Benazir Bhutto continued to pursue the country's long-standing policy of seeking influence and power in Afghanistan to balance the threat felt from India. During her first term as prime minister, training camps for mujahideen had remained open, and Pakistan had issued visas for thousands of militants from more than 20 countries traveling to the camps. The goal, many observers believed, was to maintain an army of jihadists who could be deployed to wage proxy wars against Pakistan's rivals in Kashmir and Central Asia.

Bhutto had accompanied her father to Simla when he signed the agreement with India in 1972 that ended the war triggered by East Pakistan's declaration of independence and laid down the blueprint for future peaceful relations between the two signatories. But it was evident Bhutto intended to keep a force of militants available to use as a weapon against India in Kashmir.

When Bhutto was reelected for a second term as prime minister in 1993, she was eager to encourage trade with Pakistan's neighbors in Central Asia. As part of that initiative she backed a pipeline running from Turkmenistan through southern Afghanistan to Pakistan, pro- posed by an Argentinean oil company, rather than a rival route cham- pioned by U.S. oil company Unocal. However, the region had become less stable in the aftermath of the war against the Soviets, even as the Taliban began to emerge as a power in Afghanistan in 1993. Rather than support a wider peace process in Afghanistan, Bhutto backed the Taliban, who she saw as a force that would provide security to protect the proposed pipeline and give stability to their country.

Her policy was influenced by the ISI, whose stature had risen during the Soviet occupation. After the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, the ISI sought to extend Pakistan's regional control across Afghanistan and the Central Asian republics. The ISI began funding the Taliban ("students"), a Pashtun Islamic student movement in Kandahar. Using bribery, guerrilla tactics, and military support, the ISI helped install the Taliban as rulers in Kabul in 1996 and eventually extend its control over 95 percent of the country.

During the same time that the Bhutto government backed the Taliban in Afghanistan, the Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam QUI), a strict religious party, began to gain power in Pakistan: Bhutto welcomed the party into her ruling coalition. Meanwhile the proxy war in Kashmir was heating up, again with government support. Thus, it was under Bhutto, and with her encouragement, that the Taliban rose to power in Afghanistan and the power of religious fundamentalists grew in Pakistan. Bhutto would come to regret these decisions. In a 1998 address Bhutto said that these policies had created a strategic threat to Pakistan and led to Islamic militancy, suicide bombings, weaponization of the population, the drug trade, and increased poverty and unemployment. And in an interview with the Council on Foreign Relations a few months before her death in 2007, Bhutto said, "I remember when the Taliban first came up in neigh- boring Afghanistan. Many of us, including our friends from the U.S.,

Deobahd And Barelwi Sects

A variety of schools of Islamic thought, or sects, exist among Sunni Muslims on the subcontinent. In Pakistan, Deoband and Barelwi are the two primary sects. Deoband is a town 100 miles (160 km) north of Delhi. A madrasa established there in 1867 became the headquarters for virulently anti-British Muslims who believed Western influence was corrupting Islam and who swore allegiance to religion over state. This became the model for other madrasas established throughout Pakistan after independence. Deoband is often linked to the spread of religious extremism, most notably as a seedbed for the Taliban in Afghanistan. To some degree this influence is real, as stu- dents, or talibs, from these Deoband madrasas provided the grassroots strength that gave birth to the Taliban in 1996. However, the author- ity inherent in the name Deoband is invoked to legitimize all kinds of Islamic conservatism; it is estimated some 15 percent of Pakistan's Sunni Muslims consider themselves part of the Deoband movement.

The Bareiwi sect, to which some 60 percent of Pakistan's Sunnis belong, was founded by a Sufi scholar, Mullah Ahmad Raza Khan ( 1 856— 1921), in the town of Barelwi in northern India. He is not related to the military and religious leader Sayyid Ahmad Barelwi (1786-1831). Ahmad Raza Khan taught that Islam is compatible with the subconti- nent's earlier religions, and Barelwis are apt to pray to holy men, or pirs, both living and dead. This practice is an abomination to orthodox Sunni Muslims, though Shi'i Muslims engage in similar rites. initially thought they would bring peace to that war-torn country. And that was a critical, fatal mistake we made. If I had to do things again, that's certainly not a decision that I would have taken" (Bhutto 2007).

Internal Feuds

Internal feuds had long been part of the Bhutto family legacy. Zulfikar Bhutto had feuded with family members as he rose to power, and his children followed in his footsteps. After Zulfikar's death, Benazir fought with her mother, Begum Nusrat Bhutto (b. 1929), for control of the PPP. Nusrat favored Benazir's brother, Mir Murtaza (1954-96), as heir to the Bhutto political mantle. Murtaza, meanwhile, went into exile in Kabul, Damascus, and Libya, and formed a militant breakaway PPP fac- tion called al-Zulfikar Organization. From beyond Pakistan's borders he accused Benazir of betraying their father's ideals. Murtaza also strongly opposed Benazir's husband Ali Zardari's involvement with the PPP, due to concerns about corruption.

Murtaza's supporters had been implicated in violence, including the hijacking of a Pakistan International Airline aircraft as a display of pro- test against the Zia regime, responsible for executing Murtaza's father and their political leader.

In the 1993 election Mir Murtaza had won a seat as an anti-Bhutto candidate. When he returned from Damascus after years of exile, he was jailed on the longstanding terrorism charge. Benazir Bhutto also removed her mother from leadership in the PPP. The internecine conflict was perceived as another blot on Benazir Bhutto's image. In September 1996 Mir Murtaza Bhutto was killed in a police ambush in Karachi with six companions. None of the police involved in the kill- ing were arrested, and some were subsequently promoted. A judicial review of the killings concluded it could not have occurred without the approval from the highest levels of government.

Throughout the first half of the 1990s relations between Bhutto and Leghari deteriorated. Despite earlier pledges to revoke the Eighth Amendment, Leghari instead invoked it. On November 5, 1996, Leghari

dismissed the Benazir Bhutto government, alleging crimes including cor- ruption, mismanagement, and murder. The National Assembly was also dissolved. Bhutto's husband, Asif Ali Zardari (b. 1956), who held the cabinet post of investment minister, was accused of taking bribes, receiv- ing kickbacks on government contracts, and sponsoring extrajudicial killings in Karachi. Bhutto labeled the charges politically motivated and went into voluntary exile. She and her husband were tried in absentia in 1999 and convicted. In 2001 the Supreme Court ordered a retrial. She was tried in a separate trial in absentia and convicted and sentenced to three years in prison. Facing arrest and incarceration if she returned to Pakistan, Bhutto remained in exile through the middle of the first decade of the new century. After Bhutto's dismissal, Malik Meraj Khalid (r. 1996- 97), rector of the International Islamic University, was named caretaker prime minister. In the February 1997 elections the Pakistan Muslim League (PML) won a two- thirds majority in the National Assembly and Nawaz Sharif was reelected prime minister (r. 1997-99). Nawaz Sharif's Second Government

Ever since the passage of the Eighth Amendment in 1985 during Zia ul-Haq's regime, it had played havoc with Pakistan's political stability. During his second term in office Sharif made overturning the Eighth Amendment a priority, and in April 1997, with the support of all the political parties, the Thirteenth Amendment to the constitution was adopted by the National Assembly. It gave the prime minister authority to repeal Article 58 (2)(b), the Eighth Amendment article that allowed the president to dismiss the prime minister and the National Assembly, thus restoring the original powers of the prime minister and returning the presidency to its ceremonial role. The Thirteenth Amendment also transferred the power to appoint the three chiefs of the armed forces and provincial governors from the president to the prime minister.

Nawaz Sharif also attempted to rein in the political practice of switching parties and alliances that had over the past few decades stalled progress and encouraged corruption. Because the parties and prime ministers depended on shaky coalitions to provide them with the majorities they needed to rule, politicians could threaten to aban- don their party and shift their support to rival politicians. This was mostly done to win favors or gather power, rather than to promote the public's agenda. Ministry posts, bank loans, and other benefits had been extracted by politicians as a price for continued party loyalty or for switching allegiances. Attempting to redress the problem, Nawaz Sharif introduced the Anti-Defection Bill, which the Senate and National Assembly passed overwhelmingly in July as the Fourth Amendment.

Growing Repression

However, Sharif's support for the Thirteenth and Fourteenth amend- ments was accompanied by an increasingly autocratic political style, and thus many saw the amendments as part of his attempt to stifle opposition to his rule. Sharif arrested journalists who wrote critical arti- cles about him, including respected figures Majam Sethi and Hussain Haqqani, and turned tax investigators on the editors who published their work. When the Supreme Court presided over a corruption case in which Nawaz Sharif was a defendant in 1997, his supporters attacked the court building, forcing proceedings to be suspended. No longer concerned about dismissal from his position, Nawaz Sharif let his rela- tionship with President Leghari, his primary political foe, deteriorate. The chief justice of Pakistan, Syed Sajjad Ali Shah (served 1994-97), had become embroiled in judicial disagreements with the Sharif gov- ernment, and Leghari threw his support behind Ali Shah. Sharif had party enforcers storm the Supreme Court in November and remove Chief Justice Ali Shah from office. Unable to dislodge him by dissolv- ing the government, as he had with Benazir Bhutto, President Leghari resigned on December 2, 1997.

The new president would be indirectly elected by the two houses of Parliament, the National Assembly and the Senate, along with the four provincial assemblies. On December 31, 1997, the PML candidate, Muhammad Rafiq Tarar, a senator and former Supreme Court judge, was elected to replace Leghari, having beaten the PPP and Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam candidates by a 10-to-l margin. The nation's ninth presi- dent, Tarar (r. 1998-2001) took office on January 1, 1998.

Nuclear Tests and the Economy

Early in May 1998 India's new government under Prime Minister Atul Bihari Vajpayee (r. May-June 1996, 1998-2004), leader of the Hindu Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), tested a nuclear device, thereby con- firming that it possessed nuclear weapons. Two weeks later, on May 28, Pakistan conducted its own tests of five nuclear devices, with a reported yield of up to 40 kilotons, at a nuclear test facility at Chaghi, in Baluchistan. On the same day the Sharif government proclaimed an emergency, suspending basic rights and freezing all foreign-currency accounts in Pakistani banks. The nuclear tests brought international condemnation, but Pakistan claimed it needed the weapons for self- defense against India. The United Nations passed a unanimous resolu- tion calling on both Pakistan and India to end their nuclear weapons programs, and UN secretary-general Kofi Annan (r. 1997-2007) urged both countries to sign the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty. Pakistan expressed willingness to sign the treaty if India did the same, but India declined. In June 1998, Pakistan declared a moratorium on future test- ing and India made a similar declaration.

By the time of the 1998 nuclear tests, Pakistan's nuclear program (both military and domestic) had been functioning for more than two decades with assistance from the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany), France, and China. The United States's response to Pakistan's nuclear program during this period swung between cutting off foreign aid to reinstituting assistance. Following Pakistan's nuclear tests of late May and early June 1998, the United States reimposed sanctions (excluding humanitarian assis- tance), which had been eased in 1995, against Pakistan. The U.S. sanc- tions included a "ban on financing from the Trade and Development Agency, Overseas Private Investment Corporation, and the Export- Import Bank, restrictions on U.S. exports of high-technology products, opposition to loans from international financial institutions, and a ban on U.S. bank loans to the government of Pakistan." Japan joined the United States, freezing most of its development aid to Pakistan and withdrawing support for new loans for Pakistan in international bodies (Peterson Institute, 2007).

The nuclear tests temporarily bolstered Prime Minister Sharif's popu- larity among Pakistanis, despite the fact that the effects of the sanctions on Pakistan's economy were felt immediately and that he had earlier declared a state of emergency curtailing human rights. Nevertheless, Pakistan's fragile economy, buffeted since the beginning of the 1990s, faced potential collapse. The Sharif government had to negotiate bank loans in July 1998 to cover the budgetary shortfall caused by the sanc- tions, while increasing the price of nondiesel gasoline. That same month Standard and Poor's downgraded Pakistan's rating, predicting imminent bankruptcy.

Although some of the restrictions against Pakistan were eased by the end of the year and in early 1999, Nawaz Sharif's hold on power grew ever more precarious. The poor economic situation was but one factor. Since the death of Zia, the military had been an ever-present threat to Pakistan's feeble democracy. Furthermore, "Sharif had to look over his other shoulder ... at the militant Islamists who were a powerful force in Pakistan" (Talbott 2004, 107). The latter were given support by the neighboring Taliban in Afghanistan, even as a cash-strapped Pakistan provided financial aid to the Taliban government in 1998. Sharif exac- erbated Islamists' fears (and conservative concerns) when he canceled the traditional Friday holidays. But the failure of his economic program during a period of worldwide economic growth and, especially, his attempt to exert control over the military would ultimately lead to his undoing.

After the army chief of staff, Jehangir Karamat, suggested that the military leadership be given a role in the National Security Council of Pakistan, Sharif forced his resignation in early October. Karamat had warned that Pakistan was facing grave problems, namely, an economy that was on the brink of collapse. He said Pakistan "could not afford the destabilizing effects of polarization, vendettas, and insecurity-expedi- ent policies" (quoted in Abbas 2004, 166). He was replaced by General Pervez Musharraf (b. 1943).

To strengthen his hold on power, Nawaz Sharif oversaw passage of the 15th Amendment of the constitution in the National Assembly in late October. Once passed by the Senate, it would have made sharia the supreme law of Pakistan and given the prime minister the unfettered right to rule by degree in the name of Islamic law. But unsure of the level of support in the Senate, where a two-thirds majority was needed for passage, Nawaz Sharif never brought the legislation for a vote within the 90 days required for ratification.

The Kargil Conflict

After the two countries tested nuclear devices, tensions between India and Pakistan steadily increased. In February 1999 Sharif and Vajpayee attempted to de-escalate the situation. Vajpayee traveled to Lahore by bus and was met by Sharif at the Wagah border crossing on the Grand Trunk Road. The two leaders issued the Lahore Declaration, defining the measures the countries would each take to stabilize rela- tions. The religious party Jamaat-i-Islami, a partner in Sharif's coali- tion government, opposed the visit, but all other political groups welcomed the effort to promote peace between Pakistan and India. However, Kashmir remained a flashpoint between Pakistan and India, ever threatening to plunge the two countries back into war. India had refused to hold the plebiscite mandated by a UN Security Council reso- lution in 1948, and Muslim Kashmiri fighters, supported by Pakistan, continued their battle against Indian occupation forces. The fighters infiltrated Indian-controlled Kashmir and attacked symbols of Indian rule, including army posts and police stations. In response the Indian army established border posts along the Line of Control to combat the attacks. Because of the high altitude of these posts — from about 12,000 to more than 15,000 feet (4,000-5,200 m) — troops were withdrawn during the winter.

In April 1999, before Indian troops returned to their high-altitude garrisons, Kashmiri guerrillas captured posts along mountain ridges near the Indian-occupied towns of Kargil and Drass. From their posi- tions the guerrillas launched artillery fire on National Highway 1, which runs north from Kashmir's capital, Srinagar. Pakistan denied any knowledge of or support for the guerrilla action. But India claimed identification taken from slain guerrillas revealed they were members of Pakistan's Northern Light Infantry, a paramilitary force under Pakistan's control. Beginning in May Indian forces counterattacked in what was to become the first land war in history between two declared nuclear powers. Two of its aircraft strayed into Pakistani territory, one of which was shot down. The potential for a nuclear confrontation caused worldwide concern. As the fighting continued from May into July, and the Pakistani forces were slowly pushed back, U.S. president Clinton helped persuade Pakistan to use its influence with the guerrillas to stop fighting. Bowing to international pressure, Sharif withdrew all Pakistani troops from Indian-held territory to the Line of Control. The guerrillas left the captured territory by August 1999. The withdrawal of Pakistani forces further increased Sharif's unpopularity at home.

The Coup against Sharif

The object of increasingly unflattering media coverage, Nawaz Sharif attempted to intimidate the press. In May 1999 Nawaz Sharif's secret police invaded the home of a leading journalist and critic of the regime, Najam Sethi, and assaulted and kidnapped him. An international protest forced Sharif to release the journalist. Signs of public disenchantment with the entire political process grew. In the four national elections held from 1988 to 1997, voter turnout had dropped progressively, from 43 percent in 1988 to 35 percent by 1997.

The military remained the one state institution Nawaz Sharif had not brought under his control. Karamat's departure in late 1998 had provoked great resentment in the military, placing Nawaz Sharif in a vulnerable position. As mass opposition rallies were staged against his government, Sharif, worried about the potential for a coup, planned to replace Musharraf, a veteran of both the 1965 and 1971 wars with India, with a more compliant official. On October 12, 1999, General Musharraf was on a commercial flight to Karachi, returning from a visit to Colombo, Sri Lanka, one of 198 passengers. According to a police report filed by a colonel in the army, Nawaz Sharif ordered the Civil Aviation Authority to deny the flight permission to land any- where in Pakistan. This became known as the "Plane Conspiracy" case. Simultaneously, Nawaz Sharif announced he was appointing the director of the ISI, Pakistan's intelligence service, as the military's new chief of staff. The military refused to recognize the appointment and took over Karachi airport, allowing Musharraf's flight to land with only minutes of fuel left onboard. Once on the ground, General Musharraf ordered the military to take control of the government, claiming the turmoil and uncertainty gripping the nation necessitated the action. Musharraf proclaimed himself the chief executive of Pakistan. The Thirteenth Amendment had proven insufficient to protect democracy, however flawed the democratic system may have been. Although Musharraf did not declare martial law, as had been done in previous military takeovers, Pakistan was once more under military rule.