Pakistan History: The Coming Of Islam (700-1526)

This article is an extract from |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia is an archive. It neither agrees nor disagrees

with the contents of this article.

NOTE 2: The Pakistanis’ view of their history after 1947 and, more important, of the history of undivided India before that is quite different from how Indian scholars view the histories of these two periods. The readers who uploaded this page did so in order to give others Mr. Wynbrandt’s neutral insight into Pakistan’s history. Indpaedia’s own volunteers have not read the contents of this series of articles (just as it was not possible to read any of the countless other public domain books extracted on Indpaedia).

If you are aware of any facts contrary to what has been uploaded on Indpaedia could you please send them as messages to the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name (unless you prefer anonymity).

See also

Indpaedia has uploaded an extensive series of articles about the Pakistan Movement, published in Dawn over the years, and about the various Pakistani wars with India published in the popular media. By clicking the link Pakistan you will be able to see a list of these articles. The Pakistan Movement articles are presently under 'F' (for freedom movement).

The Coming Of Islam (700-1526)

Pakistan was founded as a haven for the subcontinent's Muslims, and today they comprise more than 95 percent of the population. But it took centuries before Islam gained more than a foothold here, and centuries more before native inhabitants took up the religion in great numbers. The roots of Islam in the subcontinent extend back to the campaigns of conquest waged by Arab armies in the first years after the birth of their religion in the seventh century. Its real impact began when Muslim rulers from Central Asia invaded the subcontinent through what is now Pakistan in the 11th century. For 500 years a succession of Islamic dynasties — the Ghaznavids, Ghurids, and Delhi Sultanate among them — ruled significant portions of the region, bat- tling Hindu kingdoms and migrating nomads. These dynasties laid the foundation for one of the greatest kingdoms the world has seen: the Mughal Empire.

The subcontinent was accustomed to incursions from outsid- ers seeking land, treasures, and dominion. But unlike the nomads, Persians, or Greeks who preceded them, the Muslims introduced strong central government and many other social innovations. Their influence transformed the subcontinent and left a legacy of incomparable art and architecture, scientific knowledge, and other priceless contributions to world heritage. But in the process the Islamic tide created a schism with the subcontinent's Hindu majority that continues to define relations between Pakistan and India to this day.

Islam's First Wave

Islam, the religion brought forth by the prophet Muhammad (ca. 570-632) on the Arabian Peninsula, created a new social order and unified its formerly fractious adherents under a common faith and political community. Soon after Muhammad's death, Arab armies set off on campaigns of conquest, spreading his message in an effort to bring infidels — those who believed in neither Islam nor the religions Muhammad considered its forbears, Judaism and Christianity — into the flock. In little more than 100 years the Islamic Empire would be the largest the world had seen, stretching from the Atlantic Ocean to outposts on the Indus River. But the lands they conquered, particularly at the extremities of the empire, were often in revolt, as local rulers sought to preserve their authority. In the Pakistan region local popula- tions frequently revolted following their subjugation. Periodic military campaigns were necessary to reassert control over restive territories.

The Islamic Empire was ruled by the caliph, the spiritual and politi- cal leader of the Islamic community, or umma. The caliphate, as his office and seat of power were known, was initially in Medina, in what is now Saudi Arabia. Over the history of the empire, control of the caliphate changed hands, and the caliphate moved from Medina to Damascus (in what is now Syria) under the Umayyads (660-750) and then to Baghdad (in present-day Iraq) under the Abbasids (750-1258); ultimately the caliphate resided in Constantinople under the Ottomans (1299-1922). Concurrently, rival claimants to leadership of the faith, based on lineage to the Prophet, created dynasties of their own, rul- ing smaller empires from Cairo (the Fatimids), Cordoba in Spain (the Umayyads as rivals to the Abbasids), and other capitals.

When Islam arrived on the doorstep of what is now Pakistan, Hun and Turkish nomads and warfare between the Persians and Byzantines had rendered the region unstable and travel unsafe. The trade between East and West along the Silk Route that previously enriched the area had dwindled.

The Arabs already knew the area from their knowledge of caravan routes and their extensive sea trade. Early in the period of Islamic con- quests, between the years 637 and 643 during the reign of the Caliph Umar (r. 634-644), the Arabs mounted several campaigns in the region. Arab naval expeditions raided Debal in Sind and at Thana and Broach on the northwest coast of India. A small-scale raid against Makran in 643 paved the way for a larger invasion the following year, during which a Muslim army defeated the forces of the Hindu king of Sind near the Indus River. However, after receiving reports of the inhospitable land they had conquered, the caliph ordered the army to desist from further campaigns and make Makran the easternmost boundary of the empire.

Concurrently, the Arabs conquered Karman, an Iranian province that included southern Baluchistan, in 644, and the caliph appointed the commander of the force, Suhail ibn Adi, governor of the province. Ibn Adi mounted a campaign in Baluchistan that brought some of that region under loose Islamic control. Yet even Islamic rule in Karman was tenuous, and within a few years the inhabitants revolted. In 652 Majasha ibn Masood, who was sent by Caliph Uthman (ca. 580-656) to retake Karman, reconquered Baluchistan as well, extracting tribute payments from its subdued rulers.

In 654 an Arab army under Abdulrehman ibn Samrah was sent to pacify areas near Kabul and Ghazni, and by the end of the year all of what is now Baluchistan, with the exception of the heavily defended mountain redoubt of Kalat (then known as QaiQan), was under Islamic control. After 656 insurrections broke out in Baluchistan and Makran once more. But the umma was preoccupied with a civil war arising from disagreements over succession of the caliphate.

In 660, under the direction of Caliph Ali ibn Abu Talib (r. 656-661), Haris ibn Marah Abdi successfully led a large Arab force to reassert control over Makran, Baluchistan, and Sind. But in 663, while trying to suppress a revolt in Kalat, ibn Marah and most of his army were killed, and Islamic control over the Baluchistan region was lost. By then the caliphate had been relocated to Damascus under the dynastic control of the Umayyads, descendants of one of Muhammad's early followers. Caliph Muawiya ibn Abi Sufyan (r. 661-680), founder of the Umayyad dynasty, dispatched an overland expedition to recapture the region.

Kabul and the Buddhist holy land of Gandhara, which encom- passed Kashmir and what is now northern Pakistan, including the Peshawar plain, Taxila, and Swat, had been under the rule of the Shahi dynasty since the decline of the Kushan empire in the late second century. Between the dynasty's founding — likely by descendants of the Kushans — and its decline in the ninth century, some 60 Shahis, as the kings were known (a title believed to be derived from the Persian shah or shao of Kushan's rulers, and meant to denote kinship with the Persians, either actual or aspirational) , ruled the territory, though not without interruption. The first of the Shahis were Buddhists. An Arab army arrived at Kabul in 663 demanding its king accept Islam. For two years the Islamic warriors fought throughout the kingdom and laid siege to Kabul, bombarding it with catapults until, in 665, the city fell. The king converted, and the Arabs withdrew. The Turkish king of Gandhara, who had been Kabul's vassal, sensed an opening for himself and killed the ruler of Kabul, proclaiming himself the kingdom's lord, or Kabul Shahi. He ceded Ghazni-Kandahar in southeastern Afghanistan to his brother, and for the next two centuries this Turk Shahi dynasty controlled the area, serving as a buffer between the Arabs and contemporary northern Pakistan. The Arabs made efforts to collect tribute from the two Shahi kingdoms, which could only be extracted by waging war, and victory in their collection campaigns was often elusive. Indeed, Muawiya ordered several campaigns against the region, and only the last, which gained a foothold in Makran in 680, achieved any lasting success.

That same year a major schism erupted in Islam, again diverting attention and resources from the expansion and consolidation of the empire. A battle over the succession of the caliphate resulted in the kill- ing of Husayn, grandson of the Prophet, and one of the contenders for the caliphate. This led to the establishment of the Shi'i branch of Islam and its estrangement from the Sunni branch that continues to this day. In the aftermath of this upheaval, rulers who had been subjugated by Arab conquerors reasserted their independence. To reclaim these ter- ritories Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (r. 685-705) sent Hajjaj bin Yousuf (661-714), governor of Iraq, to restore the caliphate's rule over the northeast corner of the empire. General Qutaibah bin Muslim (d. 715) led the campaign in 699/700. He reconquered a large area of Transoxiana (located between the Oxus and Syr Darya Rivers in modern Uzbekistan) but was unable to defeat the Kabul Shahi. They reached a truce, exempting the kingdom from any tribute payments for seven years. Again, the Pakistan region escaped Arab domination and ongoing attention.

For the next three centuries (ca. 700-1000) Kabul, Peshawar, and Swat were settled by Afghan tribes who migrated from their ancestral lands west of the Sulaiman Range. At first the Kabul Shahi tried to drive the immigrants back. When that failed, the Shahi enlisted them in their battles with the Arabs and awarded the tribes villages between Kabul and Peshawar, in a region known as Lamghan, in return. The Afghanis constructed a fort in the Khyber Pass to block the advance of Arabs.

Arabs in Sind

As noted, the Arabs were familiar with the coast of the subcontinent, having sailed along its western shores plying a bustling trade with Ceylon (today's Sri Lanka) for centuries. In addition to the challenge of the elements, pirates and hostile coastal kingdoms made the voyage perilous. At the mouth of the Indus River (called the Mehran by the Arabs), the port city of Debal served as the stronghold of the Meds, one such kingdom. Noted seafarers, they engaged in trade, fishing, and piracy and extorted seafarers for protection payments.

The Meds seized the ships of any who attempted to navigate the waters they claimed without paying for safe passage. In 710 news reached Arabia that Debal pirates had seized an Arab ship, stolen its cargo, and imprisoned its crew and passengers, Arab families returning home from a visit to Ceylon. Exacerbating the outrage, the ship had been carrying gifts from the king of Ceylon to Caliph Walid I (r. 705-715).

Hajjaj bin Yousuf, then governor of the Islamic empire's eastern end, demanded the kingdom's ruler, Raja Dahir (d. 712), pay for the ship and its cargo and free its passengers. Dahir claimed he held no sway with the pirates, and negotiations broke down. Two limited campaigns against Dahir subsequently failed. Finally Yousuf received permission for a major campaign against all of Sind. His young nephew, Muhammad bin Qasim (695-715), was given command.

The Campaigns of Muhammad bin Qasim

By age 15 Muhammad bin Qasim was one of his uncle's most trusted assistants, from whom he received his education in warfare. At age 16 he served under General Qutaibah bin Muslim, where he distinguished himself with his military planning. Six months of preparation preceded Qasim's Sind campaign. Before commencing the assault, Qasim married his uncle's daughter. His attack force included 6,000 Syrian horsemen, 6,000 troops on camels, and 3,000 Bactrian camels to carry supplies. Ships carried five large catapults. The largest, called Uroos, Arabic for bride, required a force of 500 men to operate. A network of couriers was organized for battlefield communications.

The coastal strip of Makran was the first region of Sind attacked and the first to fall. Armabil (contemporary Bela in Baluchistan) was next. Joined by the troops from the previous two unsuccessful Arab attacks on the Hindu kingdom, Qasim set out for Debal on the Indus River delta, where a naval expedition from Basra (in present-day Iraq) was also directed. The sea and land forces arrived at Debal on the same day, the former having been about a month in transit. They dug trenches and awaited orders to attack.

Residents of Debal believed their gods would protect them as long as the flag waved from their central temple. Qasim, learning this, made the flag his primary target and had the catapult arm of Uroos shortened to hit the target. Debal's flag was soon knocked down, the fortifications breached, and the town conquered, though its leader fled. Qasim issued a decree:

All human beings are created by Allah and are equal in His eyes. He is one and without a peer. In my religion only those who are kind to fellow human beings are worthy of respect. Cruelty and oppression are prohibited in our law. We fight only those who are unjust and are enemies of the truth. (Hussain 1997, 103)

A treaty was promulgated by one of the officers: On behalf of the Commander of the Faithful, I, Habib bin Muslim, grant amnesty to all the people of Daibul [Debal] and hereby ensure their personal safety, security of their temples, women and children and their property. So long as you will pay jizya [a tax of protection levied on non-Muslims] we shall abide by this agreement. (Ibid.)

Hindu rule in the region had been marked by oppression and cruelty toward both the large Buddhist population and lower-caste Hindus. By their tolerance the Muslims, as they had in other conquered regions, soon won over the populace, who had little regard for their previous rulers.

Continuing the campaign, Qasim next attacked Neronkut, a pre- dominantly Buddhist city farther upriver on the Indus, near pres- ent-day Hyderabad, which was under the rule of Raja Dahir's son, Prince Jay Singh. Siege equipment was loaded back on the ships and floated up the Indus. After a six-day march the troops arrived at the city. Dahir ordered his son to vacate the city and join him at Brahmanabad, leaving Neronkut in the command of a Buddhist priest who turned the city over to Qasim and provided fodder for the Arab's camels and horses.

Qasim now marched on Sehwan, under the rule of Dahir's cousin, Bhoj Rai. The city's Buddhist community asked Bhoj to capitulate, but he attempted an attack on the rear of Qasim's forces. While the Arabs planned their counterattack, the Buddhists secretly sent Qasim word that the commoners did not support Bhoj Rai and advised the Arab commander their army was largely ineffective and unready to fight. After another week of battle, Bhoj Rai fled. Qasim organized an Islamic administration of the conquered city. The fortress was later retaken by its former ruler, but was won back by Muhammad Khan, one of Qasim's generals. Sehwan became a center of Islamic power in Sind.

With losses mounting, local rulers and governors began offering submission to Qasim and providing supplies for his army. Leaders who submitted were treated generously. All were allowed to continue prac- ticing their religion.

Final Victories

Meanwhile, the Arab's advance bogged down at the Indus. Blocked by Dahir's son from crossing the river at Brahmanabad, the army encamped on its banks. After several weeks their supplies began to run out. Horses were slaughtered for food, and soldiers weakened from hunger. Qasim sent Yousuf a request for supplies and received 2,000 horses along with vinegar-soaked cotton, intended perhaps as a palliative for the rampant vitamin deficiency. The Arabs finally built a bridge of boats and after 50 days crossed the Indus, making for Rawar, joined by more local rulers who switched sides against Dahir. In June of 713, following several days of skirmishes, Dahir, leading his forces from atop an elephant, came out to face Qasim in a battle that would decide the fate of Sind. Early in the battle a blazing arrow struck the trunk of Dahir's elephant, setting its ornamental silk covering on fire. The panicked elephant ran, leaving Dahir's abandoned forces frightened and confused. Returning to the battle on horseback, Dahir tried to lead his troops but was decapitated by an Arab swordsman. His army was routed by the Islamic army and their newfound local allies. After the battle the city of Rawar surren- dered, as did Brahmanabad. But strongholds remained. The Multan fort resisted the Arabs' months-long effort to conquer it. Finally the channel that supplied the fort with its water was discovered and cut off, and the fort surrendered. To secure the protection of their temple, the Multanis gave a fortune in treasure to Qasim, a sum large enough to help pay for the entire expedition. From here Qasim sent forces to Kashmiri strong- holds on the Jhelum River and to the borders of the Kanauj kingdom in northern India.

During the campaign Yousuf died, as did Caliph Walid I soon after Multan had fallen. The new caliph, Sulaiman (r. 715-717), ceded power in the empire's east to a rival Arab faction. Yousuf's family members were now regarded as enemies by the new ruler. Qasim was recalled and executed before further advances were made. Nonetheless, Sind became Islam's path (bab-al Islam, or door of Islam) to the subcontinent.

Sind after Muhammad bin Qasim

Despite the halt in the advance of the Arab forces, for the next 200 years Sind remained part of the Islamic Empire, under the direction of at least 37 Arab governors who oversaw the administrations of local rulers. Islam spread while Buddhists and Hindus continued to prac- tice their faith. Local revenue officials collected jizya and zakat (a tax on Muslims). Mosques sprouted in every city, joining the Hindu and

Buddhist temples and shrines. Disputes between Muslims were settled by qadis, Islamic judges, according to Islamic law Disputes between Buddhists and Hindus were settled by Brahman priests of the local pan- chayat, or council. Over time the Islamic and Sindi customs intertwined to create a new culture. Underscoring the deep bond that grew, Sindi became the first language into which the Qur'an was translated.

Some 10 years after Qasim's conquests, Junaid, an Arab governor, tried to expand Sind's empire to the east by annexing Kutch, the coastal area between the mouth of the Indus and the Gulf of Kutch, and Malwa. But in 738 the Arabs were defeated at the Battle of Rajasthan by the Pratihara Rajputs of the Thar Desert. A northward expansion into Punjab from Multan was halted with Kashmiri help under the leader- ship of Laladitya (724-760), one of Kashmir's greatest rulers. Laladitya maintained an alliance with the Tang dynasty in China, as did Turkish Shahi rulers in Kabul who sought allies against the Arabs.

The Arabs were not the only force seeking to gain territory in the region. Tibet ruled much of Nepal, northern India, and what is now Bangladesh. In about 726 Tibet conquered Skardu, which lay to Gilgit's east. Seeking to counter their growing power, in 747 the Chinese sent troops to southern Chitral, an area in modern northwest Pakistan, where they replaced the pro-Tibet ruler, putting his brother, who was closer to the Chinese, on the throne. But Tibet's westward expansion continued, finally winning dominance over the Gilgit Valley and upper Chitral.

Such was the importance of maintaining strong ties with China that before the leader of Kabul and Swat passed rule to his son, he sought approval from China. Underscoring China's interest in defending its flank, China also granted the son the title "Brave General Guarding the Left" in approving the succession.

Meanwhile the resurgent Arabs resumed efforts to expand their empire in Central Asia. The conflict between the Arabs and Chinese for control of this area ended at the Battle of Talas in 751, with the Arabs emerging victorious. In the aftermath most of the Turkish nomads who had settled in the region converted to Islam. Yet despite the Arab victory, the area encompassing Gandhara, Swat, and Kabul remained largely independent.

The Abbasids

By this time the caliphate, the office of the political and spiritual ruler of the Islamic Empire, had moved to Baghdad, and the Abbasid dynasty of caliphs was in power. It was under the Abbasids that the intellectual flowering called the Golden Age of Islam took place. The Golden Age reached its height during the reign of the Abbasid Caliph Harun al- Rashid (r. 786-809). His death created unrest throughout the empire, as local rulers sought to assert independence while his sons Muhammad al-Amin (r. 809-813) and Abdullah al-Mamun (r. 813-833) fought for control of the empire. While the two were thus occupied, the governor of Transoxiana proclaimed his independence, backed by allies including Qarluq Turks, the Shahi of Kabul, and the Tibetan empire. Al-Mamun finally prevailed in the struggle for succession and quickly dispatched forces to subdue Transoxiana's rebellious ruler and his allies.

In 817 the Arab forces captured Kabul's ruler, Ispabadh Shah, at Merv, in present-day Turkmenistan. Taken to Baghdad and brought before the caliph, the shah converted to Islam. His successor as lagatur- man, another title by which Kabul's rulers were known, was allowed to rule the Kabul region, but was assessed twice the normal tribute, which he paid to the governor of Khorasan, the Islamic Empire's northeastern frontier state.

A second campaign sent Muslim troops to upper Chitral as far as the Indus River to forestall future attacks from Tibet. Here they planted the black flags of the Abbasid caliphate.

In suppressing local rebellions throughout the empire, al-Mamun came to rely on several generals. In Khorasan the general who directed al-Mamun's victory over his brother, Tahir ibn Husain (d. 822), a Persian by birth, was so effective he became the de facto ruler of the region, though he continued to swear fealty to the caliph. Like Tahir himself, his troops were primarily Persian Muslims. This marked the first time the Islamic Empire came to depend on non-Arabs for its security. The increasing reliance on non-Arab Muslims would have a dramatic impact on the empire, as eventually these military leaders took over the empire while retaining the Abbasid caliphs as figureheads. The Turks in particular, as a result of the Abbasid practice of capturing Turkish boys and educating and training them in the military arts, would come to occupy premier positions in the Abbasid power structure.

However, in the late ninth century Tahir's successors lost control of the territory to a Muslim coppersmith from Sistan (now eastern Iran), Yaqub bin Laith (r. ca. 867-879). Unable to defeat Yaqub, the Tahirid governor gave him authority over eastern Persia and Afghanistan, creat- ing the Saffarid (from saffar, coppersmith) Emirate.

In 870/1 Yaqub attacked and defeated the Hindu Shahi ruler of Kabul, even though Kabul was nominally a suzerain of the Islamic THE REGION'S PART IN ISLAM'S GOLDEN AGE

The region that is now Pakistan played a prominent role in the era of inquiry and discovery known as the Golden Age of Islam. Numerous works that had been created in what is now Pakistan when it was part of the Sassanian Persian Empire (224-651) were now translated from Pahlawi into Arabic. This includes the tale of Sinbad the Sailor, later collected in A Thousand and One Nights. Chess, which became popular throughout the Arab world, also originated in the Indian subcontinent and came to Persia under the Sassanians. A family from Punjab, the Barmakids, played a key role in the transfer of knowledge from the region to the Islamic Empire. Originally Buddhist priests, the Barmakids were masters of the medical arts. They settled in Balkh, along the current Afghan-Uzbekistan border, and converted to Islam. Later they became secretaries and advisers to the Abbasid caliphs until they lost power in 803.

A raid against Kashmir by the governor of Sind during this time brought the famous Sanskrit scholar Mankha to Baghdad. After study- ing its tenets, Mankha converted to Islam and thereafter spent his life translating works from Sanskrit into Arabic. Mathematics also benefited from Islam's exposure to India. What are commonly called Arabic numerals in the West originated in a numbering system from the subcontinent. The numeral zero was part of this system and was probably invented centuries earlier in the Taxila region. Some 700 years later this knowledge passed to the Western world during the Renaissance. Empire. To win favor, Yaqub sent treasures back to the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad. In return the caliph extended Yaqub's authority over all of Persia and Sind. For the next decade Yaqub appointed the governor of the Hindu Shahi kingdom. By 876 Yaqub was threatening the Abbasid caliphate itself. He marched his army to Baghdad but was defeated near the city Though not routed, Saffarid power began to decline. By 903 his descendants' rule was again confined to Sistan.

Another Persian group, the Samanids, composed of nobles and landowners, played a large role in pushing the Saffarids back to Sistan. For their service the caliph ceded them rule of eastern Muslim territories including Persia and Afghanistan. Samanid rule lasted from 903 to 999 and marked a rare period of tranquility and prosper- ity in Central Asia.

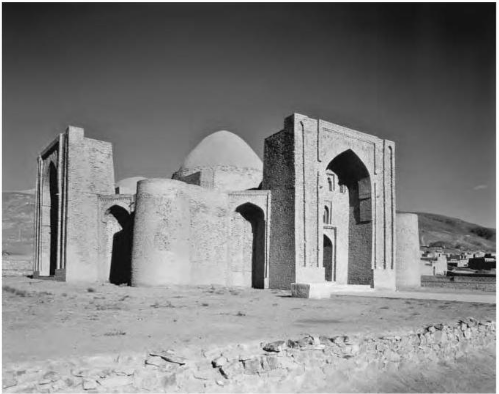

With the Saffarids gone, by 900 the Kabul Valley was free of Muslim governance, and the Hindu Shahis' rule was restored. The Hindu Shahi dynasty had been founded by the Brahman minister Kallar in 843. The Turk Shahis who preceded him had been mostly Buddhists. Kallar had moved the capital east from Kabul to Ohind, seat of one of the Hindu kingdoms that dominated the region, on the west bank of the Indus River, near present-day Attock. Ohind had historically been a major crossing point of the river. With Central Asian trade routes now under Arab control, overland trade again flourished, and the city became an important trade city. Here precious gems, textiles, perfumes, and other goods made their way west from the northern subcontinent. Illustrating the importance the region played in international trade of the era, coins minted by the Shahis have been found throughout the subcontinent, Central Asia, and even eastern Europe. The city also became a center of education and culture. But education at this time was confined to preservation rather than expansion of knowledge. Great Hindu temples were built by the Shahis and filled with idols, many of them later taken by Arab raiders. Some of their temples can still be seen in the Salt Range at Nandana, Malot, Siv Ganga, and Ketas. Ruins of these shrines are also on the west bank of the Indus, while the remains of old fortresses dot the hills of Swat.

While the Hindu Shahi kingdom flourished in the northwest of present-day Pakistan in Sind and Makran, small Muslim kingdoms developed. Mansurah and Multan were the two main principalities. The ruins of Mansurah attest to its former grandeur, while the Hebadi dynasty of Multan was well known for its devotion to learning and the welcome it gave scholars.

Kashmir's power continued to grow during this period, and it came to control parts of Punjab. The Hindu Shahi kingdoms formed an alli- ance to block any further Kashmiri expansion. Under Jayapala Shahi (r. 964-1001), the most celebrated Hindu Shahi ruler, the Hindu Shahi kingdom extended from west of Kabul to east of the present Pakistan- India border, and in the north from the valleys of Bajaur, Buner, and southern Kashmir to Multan in the south.

Islam's Second Wave

For some 350 years Islamic rule in what is now Pakistan and India was confined to small areas or exercised through local vassals. But begin- ning in the 11th century, after campaigns of conquest waged by Muslim rulers from Central Asia, direct Islamic rule would extend over large swaths of the subcontinent.

The Hindu Shahi kingdom's western border abutted Ghazni, ruled by Turkish Muslims and their king, Sebiiktigin (r. 977-997). Seeking to expand his kingdom, Jayapala, the Hindu shahi, raised an army and marched on Ghazni. After days of battle the Turkish Muslims had gained the upper hand. Sebiiktigin accepted Jayapala's promise of money, territory, and elephants in exchange for peace. But Jayapala reneged on the agreement, incarcerating the Turkish officers sent along to assure his compliance. Sebiiktigin marched his army in pur- suit, burning temples and destroying property along the way. Though outnumbered by Jayapala's massive force, skillful deployment of the Turkish cavalry earned victory for the Muslims The defeated Jayapala ultimately committed suicide.

Mahmud of Ghazni

Sebiiktigin was succeeded by his son, Mahmud of Ghazni (r. 998-1030). Under Mahmud the Ghaznis extended their rule into non-Islamic northern India, adding great wealth to their kingdom. Concurrently Islam spread throughout the region and became the dominant social and political force in what is now Pakistan.

By this time the Islamic Empire had split into rival caliphates: the Abbasids, who ruled from Baghdad, and the Fatimids in Cairo, whose hereditary rulers claimed legitimacy to the caliphate through their descent from Fatima, daughter of the prophet Muhammad. Multan had been under the control of Fatimid loyalists. Mahmud, who supported the Abbasids, attacked and defeated Multan and its Hindu allies. He also continued his battles against the Hindu Shahi dynasty, which grad- ually lost ground, from 1000 to 1026. In 1001 he conquered Peshawar, and it became an important center of the empire. As he conducted his military campaigns, Mahmud also built his capital of Ghazni into the greatest city east of Baghdad. The Persian scholar al-Beruni (973-1048) accompanied Mahmud back to Ghazni after his conquest and annexa- tion of Khorasan and also on campaigns in the subcontinent, becoming the first Muslim scholar to study Indian society and languages.

For nearly 200 years Mahmud and his successors ruled what is now Pakistan. During the Ghaznavid period Muslim missionaries and scholars traveled throughout the kingdom spreading the prophet Muhammad's message. One of the first, Shaikh Ismail Bohkari, began preaching in Lahore in 1005. Islam was embraced by more Afghan tribesmen as well as the Janjuas rajputs of the Salt Range and others in the Punjab. Gradually it was accepted throughout the population.

Today Mahmud is considered a hero in Pakistan but reviled in India for forcing Hindus and Buddhists to convert to Islam and for the sack- ing and plundering of Hindu temples.

In 1018 Mahmud conquered Kanauj, marking the end of the Gurjara- Pratihara dynasty. The Pratiharas were superseded by another Rajput clan, the Rathors, who ruled under Mahmud and his successors.

With the stability wrought by the Ghaznavids, trade along the silk routes in Punjab that had been disrupted by warfare among local king- doms revived. Ghazni became an important trade center, and Mahmud minted coins to facilitate commerce. Among Hindus trade had always been an occupation of the lower castes. But with the growing profits, by 1030 Brahmans were also involved in mercantile activities.

Masud I

Mahmud was succeeded by his eldest son, Masud (r. 1031-41), who reorganized the administration in Lahore, a Ghaznavid vassal state, to assure control over the new territories. Masud sought to keep Muslim leaders separate from their Hindu subjects without alienating the masses. He instructed Turkish officers not to drink, play polo, or socialize with Hindu officers, nor display religious intolerance toward them. When the governor of Lahore raided Banares (modern Varanasi) and failed to give Masud any of the spoils, Masud showed his own tolerance by selecting a Hindu general, Tilak, to lead a retaliatory attack on Lahore.

However, the empire began to crumble. Multan regained its indepen- dence after Mahmud's death and again allied itself with the Fatimids. The western part of the empire began to fall to the Seljuks, the Turkish mercenaries who had taken the reins of the Abbasid caliphate. Masud's father, Mahmud, had always kept a Seljuk prince as a hostage to gain leverage over the Turks. But a hostage was insufficient to deter them now. The Seljuks continued their onslaught, and at the Battle of Merv (1040) they drove the Ghaznavids from Khorasan. Masud was prepared to accept defeat, but his own Turkish troops rejected his submissive attitude and, during their retreat, rebelled at the Indus River crossing at Ohind. Masud was arrested along with his wife and some followers, and a month later he was beheaded.

After Masud

The Ghaznavid dynasty survived Masud's execution. While the Seljuks assimilated their gains in Khorasan, Masud's son Maudud (r. 1042-49) defeated Masud's younger brother to take control of the empire. During Mau dud's reign three Hindu rajas made repeated attempts to drive the Ghaznavids from the Punjab. The Hindus succeeded in regaining Kangra and Thanesar but were thwarted at Lahore during their siege. A Turkish marksman killed the Hindus' leader, and his troops withdrew in disarray. Maudud later sent one of his sons to oversee Peshawar, and another to run Lahore.

During this period southeastern Sind was ruled by the Sumras, one of the first clans to accept Islam following Qasim's campaigns. They assisted the Arabs in their governance of Sind, though they later devel- oped an allegiance to the Fatimids. By the mid- 11th century they had assumed independent rule of southeastern Sind, making their capital at Kutch. More than a score of Sumra rulers presided over the Sumra kingdom over the next two centuries. Ghaznavid rule in what is today northern Pakistan continued under Ibrahim (r. 1059-99) and his son Masud III (r. 1099-1115). Though the Seljuks had increased their power in the Islamic Empire, treaties with them kept the western flank of the Ghaznavid kingdom secure. Lahore became a major cultural center in the Muslim world during this time. Among its important figures was Syed Ali Ibn Usman of Havver, also known as Data Ganj Bakhsh (d. 1077). A noted Muslim theolo- gian, he wrote poetry and scholarly works, helping spread Islam in the region. His treatise on Sufism was the standard text on the subject for centuries. His former home in Lahore is still visited by thousands annu- ally. Lahore's prominence as a center of learning and the arts continued into the reign of Ibrahim's grandson, Shirzad (r. 1115).

The Ghurids

In a region called Ghur, the desolate hill country south of Herat, Afghanistan, a blood feud precipitated by Bahram Shah (1118-52), the ruler of Ghazni, gave birth to a new kingdom that would sup- plant Ghaznavid rule. Bahram executed a prince of Ghur, provoking one of the prince's brothers to attack Ghazni and force Bahram into a temporary retreat. When Bahram again set upon the Ghurid forces, he captured the Ghur prince who had led the assault and barbarously put him to death. The remaining Ghurid princes, determined to avenge the deaths of their brothers, mounted an overwhelming attack on Bahram's kingdom in 1150/1, completely destroying Ghazni and earning their leader the honorific Jahan-Soz, or Earth Burner. The Ghaznis moved their capital to Lahore.

The Ghurids, now independent of Ghazni rule, attacked Herat but were defeated by the Seljuk governor. But in 1153 the Seljuks fell to another Turkish tribe, the Ghuzz, who went on to conquer most of Afghanistan, including Ghazni. After 1160 the Ghuzz kept the Ghaznavids confined to what is today northern Pakistan.

In 1173 the Ghurid ruler, Sultan Ghiyas-ud-din Muhammad, assisted by his younger brother, drove the Ghuzz from the Ghazni region. The younger brother, Muhammad of Ghur (1162-1206), began raiding the subcontinent, using the Gomal Pass as his transit point. In 1175 Muhammad of Ghur occupied Multan and Uch (near present-day Bahawalpur). Following in the footsteps of Mahmud of Ghazni, he set out across the Thar Desert in Rajputana to raid Gujarat. He was defeated by Chalukya Raja of Kathiawar (today's northwest India) in 1178. Bloodied but unbowed, Muhammad of Ghur attacked Ghaznavid lands, taking Peshawar in 1179. He defeated both the Gakkars, power- ful tribes that lived in the hill country between the upper Indus and Jhelum Rivers, and the Ghaznavid ruler Khusrau Malik (r. 1160-87), taking Sialkot in 1185 and occupying Lahore in 1186/7. Muhammad's conquest of Lahore marked the end of the Ghaznavid dynasty.

In 1190/1 Muhammad conquered Bhatinda, India, in the territory of the Chauhan. But once Muhammad set off to return to Ghazni, the Chauhan ruler, Raja Prithviraj (1165-92), sent forces to retake the fortress at Bhatinda. Muhammad reversed his course and met Raja Prithviraj 's army at Tarain (also Taraori, near the present-day city of Thanesar, India). Muhammad's forces lost the battle, though Muhammad survived. Seeking revenge, he returned in 1192. At the Second Battle of Tarain, Muhammad captured Prithviraj and completely routed his numerically superior forces. The victory opened northern India to Muslim conquest. The raja's queen and attendants immolated themselves in the style of defeated Rajput women. Delhi was now under Muslim rule, as it would remain for more than 650 years, the capital of a series of powerful Muslim dynasties, until the last Mughal was deposed by the British.

By 1203 Muhammad had established Ghurid rule of the Ganges River basin. From his capital in Firoz Koh in Ghur, Afghanistan, he ruled over much of the subcontinent, sharing power with his older brother. To the west lay Khwarezm, extending from Persia into Central Asia, ruled by a Turkish Muslim dynasty. Shortly before his death in 1206, Muhammad failed to defeat the shah of Khwarezm, Ala-ud-Din Muhammad II (r. 1200-20, d. 1231) in battle. He was assassinated in his sleep, bringing the Ghurid empire to its end. The shah of Khwarezm gained control of all of Transoxiana (Turkestan), then conquered the Ghurid territories west of the Indus. Muhammad of Ghur's governors established independent fiefdoms east of the river. A top Ghurid gen- eral, Qutb-ud-Din Aibak (r. 1206-10), or Aybak, who had conquered and been appointed governor of Delhi, made that city his capital. He founded the first of a series of Muslim dynasties that would be known as the Delhi Sultanate.

The Delhi Sultanate

The Delhi Sultanate (1206-1526) established Islamic rule throughout much of the subcontinent, and it maintained its predominance in the region for more than three centuries. The sultanate's formative period, 1206-90, is often called the Slave dynasty because the rulers of this era were Turkish generals who began their lives as slaves. They took the title sultan.

The Slave Dynasty

Qutb-ud-Din Aibak, the first sultan of Delhi and the first Muslim ruler to make his capital in India, was born in Transoxiana. Captured and sold into slavery as a child, he received a good education and was schooled in archery and horsemanship. Upon the death of his owner, the chief qadi of Nishapur, in Khorasan, Aibak was sold to Muhammad Ghuri, eventually becoming his most trusted general. Aibak conquered much of northern India during the Ghurid campaigns of conquest. A builder as well as battler, he constructed mosques in Delhi and Ajmer, Rajasthan. Aibak was in Lahore subduing a Gakkar uprising when Muhammad died, and he established his capital in that city before mov- ing it to Delhi. He died in an accident while playing polo in 1210.

SUFISM Sufism developed in the 1 0th century as a reaction to the increased worldliness of Islam in the aftermath of the empire's expansion and growing secularism. It was enthusiastically adopted in the Sind and Punjab. Sufis practiced asceticism and eschewed the trappings of materialism. The populations in these regions were familiar with these practices, as they had a history of asceticism under Buddhists. By the 13th century Multan and Uch were flourishing centers of both trade and Sufism, drawing many merchants, Sufis, and scholars. Here Sufi saints and Muslim trade and craft guilds were closely linked. Indeed, during lltutmish's reign, Multan became the site of the first Sufi center, or khanqah, established by Shaikh Bahand-din Zakariyya, or Baha-ud- din Zakariyya (ca. 1 170-1267). He introduced the Suhrawardi order of Sufism to the subcontinent. The Suhrawardis were fervent proselytiz- ers, responsible for converting many Hindus to Islam.

The Chistiyya order of Sufis was the second to establish a khanqah. The order was founded in Chist, a village near Herat, Afghanistan, by Khwaja Muin-ud-din Chisti (b. ca. 1 141-1236). By the time of his death Chistiyya khanqahs had been founded throughout the Delhi Sultanate. Baba Farid Shakar Gunj, or Farid-ud-din Ganjshakar (ca. 1180-1266), his successor, is considered the first great poet of the Punjabi language.

Samarkand CHAGATAI MONGOLS/ Aibak was briefly succeeded by his son, Aram Shah (r. 1210-11), but owing to his reputed laziness and incompetence, Turkish officers deposed him in favor of Aibak's son-in-law, Shams-ud-Din, who ruled under the name Iltutmish (r. 1211-36). Iltutmish was faced with insur- rections throughout the empire, but methodically took on the young sultanate's former vassals and then began expanding the empire's terri- tory He defeated Taj-ud-Din Yalduz, or Yulduz, in Lahore in 1215 and Nasir-ud-Din Qubacha (r. 1206-28), who ruled Multan, upper Sind, and portions of Punjab, in 1215 and again in 1228. Both these foes were former slave generals who served under Muhammad of Ghazni, as had Iltutmish's father-in-law, Aibak, founder of the Delhi Sultanate. The Khalji in Bengal, a kingdom also founded by slave generals for- merly allied with Aibak, were defeated after Iltutmish mounted three campaigns against them. The Abbasid caliphate recognized Iltutmish's rule and sent envoys to Delhi from Baghdad in 1229. By the time of his death in 1236, the Delhi Sultanate's territory was consolidated.

Mongols on the Doorstep

Under the reign of Iltutmish the sultanate — and the region that is now Pakistan — contended with the depredations of armies of Mongol nomads that swept into the region led by Chinggis, or Genghis Khan, (ca. 1162-1227). Chinggis Khan and the Mongols first came to the area in 1221 in pursuit of Jalal-ud-Din Mengiiberdi, son of the shah of Khwarezm, Ala-ud-Din Muhammad II. The Mongols had overrun Khwarezm in 1220. Ala-ud-Din Muhammad had escaped but died soon after, and Mengiiberdi (r. 1220-31) fled east with a small army. The Mongols caught and defeated them at the Battle of the Indus. Mengiiberdi and some of his followers escaped into India. Chinggis Khan continued into the subcontinent as well, plundering and sacking his way through Punjab and Multan. Iltutmish is said to have declined

Mengiiberdi's request for sanctuary in Delhi

By the end of Iltutmish's reign the Mongols controlled much of what is now Pakistan as well as most of Central Asia and parts of Europe. Now that the silk routes were under their jurisdiction, the Mongols switched from raiding caravans to taxing them. In the Pakistan region, towns west of the Indus submitted to Mongol rule while the Delhi Sultanate claimed all lands east of the river. Local rulers in the Indus region tried to remain neutral.

After the death of Chinggis Khan the Mongol empire split into four parts. Present-day Pakistan came to be known as Chaghatai, named after the descendants of Chaghatai, Chinggis Khan's second son. Mongol raids continued to ravage the region, ultimately depopulating the provinces of today's Baluchistan and NWFP. Marco Polo (1254-1324) was held pris- oner here, and after his escape wrote of the Chaghatai: "They know well the localities . . . they come here by the dozen thousands, sometimes more, sometimes less. Once they seize a plain, no one escapes, neither men nor cattle. If they make their mind to plunder, there is nothing that they cannot take hold of. When they take a folk in captivity they slay the old and take away the young whom they sell as slaves" (Hussain 1997, 145). The raids also drew Baluchi and Afghan tribes into the western Pakistan area, as the land was now emptied, introducing two important ethnic groups into the population of Pakistan.

On the east side of the Indus Iltutmish was succeeded by his daugh- ter Razia Sultana (r. 1236-40). But military leaders were unwilling to recognize her rule. Turkish nobles rebelled against her and seized power, but were unable to agree on a leader. Iltutmish's youngest son, Nasir-ud-Din Mahmud (r. 1246-66), was his last descendant to rule the sultanate. He spent most of his time in prayer, turning the affairs of the state over to a Turkish slave, Ghiyas ud Din Balban, who gradually gained control of the empire. Balban (r. 1266-87) took the throne upon

Nasir-ud-Din's death

The sultanate had grown in part due to the ambitious corps of Turkish officers that led its military victories. Their contributions were reflected in the rule by consensus previous sultans had observed. Balban dispensed with this practice and shifted composition of the military garrisons from Turkish to Afghan forces, lessening the chances of an attempted coup by these officers. Concurrently he introduced pomp and ceremony into the state's affairs. From his subjects' point of view, his major contribution was the construction of forts from the Indus to Delhi, built to protect the region from the Mongols. He also rebuilt towns and villages throughout Punjab the marauders had destroyed, including the reconstruction of Lahore. Balban's eldest and most capable son, Muhammad, governor of Multan and Sind, engaged the Mongols successfully in several skirmishes, but died in battle.

Balban was succeeded by his inexperienced and undisciplined 18- year-old grandson, Muiz ud din Qaiqabad (r. 1286-90). Four years later, after suffering a debilitating stroke, Qaiqabad named his three- year-old son Kayumars (r. 1290) as ruler in his stead. A group of Turkish nobles asked Jalal-ud-din Firuz Khalji (r. 1290-96) to step in, and the elderly general accepted. But the sultanate was in decline, as it had been since the reign of Iltutmish. The corps of ambitious Turkish officers who helped create the kingdom now gave in to avarice over the spoils of the dynasty's demise, further fragmenting the empire. Some resented the increasing power of the Khalji clan, considered to be of Afghan rather than Turkish origin.

The Khalji Dynasty

The Delhi Sultanate continued battling the Mongols after the fall of the Slave Dynasty. By the time Jalal-ud-Din Khalji took the throne, he had spent years battling the Mongols. Now old and nonthreatening, he was unable to keep either his officers or the Mongols in check. He appointed his battle-hardened and ruthless nephew Ala-ud-Din Khalji as governor. Later Ala-ud-Din Khalji (r. 1296-1316) succeeded him to the throne. Battles with and victories against the Mongols marked his rule.

Soon after Ala-ud-Din assumed rule, Punjab was invaded by an army of 100,000 Mongols. Ala-ud-Din drove off this first wave. A year later the Mongols returned and captured Sehwan, but Ala-ud-Din reclaimed the city, capturing thousands of Mongols and their leader. In 1299 the Mongols laid siege to Delhi. Advisors urged Ala-ud-Din to make peace with the Mongols, but he refused: "If I were to follow your advice, how could I show my face, how could I go into my harem, what store would the people set by me?" (Hussain 1997, 151). Instead he attacked and defeated the Mongol army.

An able administrator as well as warrior, Ala-ud-Din reorganized the state, ending local insurrections by reorganizing local rule and creating a centrally paid army that could stave off Mongol attacks anywhere in the kingdom. Ultimately he drove the Mongols from all of Pakistan and carried the war to their strongholds, pillaging Kabul, Ghazni, and Kandahar. Ala-ud-Din also conquered the Sumra kingdom and expanded Muslim rule deep into the subcontinent. Expeditions in 1307, 1309, and 1313 brought victories as far as the tip of the Deccan peninsula. Local rulers held their positions but paid tribute to Delhi.

Ala-ud-Din's conquest of southern India brought an infusion of new cultural elements into the Delhi Sultanate. Artisans and craftsmen from the conquered areas flocked to the prosperous cities of the kingdom. This infusion resulted in cultural advances that included the sitar, pur- portedly invented by Amir Khusro, or Khusrau, Dehlawi (1253-1325), a Muslim intent on creating a separate Islamic art tradition based on the subcontinent's own cultural roots. The stringed instrument was derived from the Persian tanpura and the South Indian vina. Amir Khusro is also credited with inventing the tabla ("drum" in Arabic), a percussion instrument based on the South Indian drum. (Amir Khusro makes no mention of creating these instruments in his own writings.)

A long illness compromised Ala-ud-Din's administrative and leader- ship capabilities, and he ceded control of the empire to his general, Malik Kafur, a former Hindu slave. Confusion reigned after Ala-ud- Din's death until 1320, when Punjab's governor, Ghias-ud-Din Tughluq, accepted the request of Muslim nobles to take the throne.

The Tughluq Dynasty

A former governor of Punjab, Ghias-ud-Din Tughluq (r. 1320-25) reasserted the power of the sultanate in Delhi, the Deccan, and Bengal, which had ebbed while Al-ud-Din focused on his southern conquests. A bold general and able administrator, he reversed some of Ala-ud-Din's unpopular policies, granting iqtadars — local administrators who raised land revenues and maintained troops for the sultanate — greater control over their lands and lower tribute payments. His short reign ended when he died in the collapse of a poorly built pavilion.

Muhammad ibn Tughluq (r. 1325-51), Ghias-ud-Din's son, was similar to Ala-ud-Din in his ruthlessness and ambition, but unthink- ing in his application of those traits. He reimposed the unpopular local governance policies of Ala-ud-Din that his father had reversed. To exercise greater control over the Deccan, he moved the capital from Delhi to Deogir, renaming it Daulatabad, and ordered all inhabitants to move from Delhi to the new capital. Many died during the trip south. Ibn Tughluq also planned to have all the inhabitants of Multan move south. When the governor refused, Ibn Tughluq came to the city and demanded that all its citizens be put to death. The inhabitants were later pardoned after the intercession of Shah Rukn-e-Alam (1251-1335), an influential cleric whose mausoleum is today one of Multan's most famed edifices. In 1347 Ibn Tughluq restored Delhi as the sultanate's capital and allowed people to return to the city.

Ibn Tughluq's attempt to introduce a new copper and brass currency was a failure. He raised a large army, intending to mount a campaign against Khorasan, under the rule of Persian-allied Muslim rulers, and Tibet in the north, possibly to gain gold and horses, as rebellions were reducing the kingdom's income. However, he was unable to follow through on his plans. Natural disaster added to his people's misery. A drought during the years 1335-42, one of the worst in the subconti- nent's history, caused widespread famine and led to a revolt, despite Ibn Tughluq's efforts to provide relief.

Where his father and grandfather had been content to leave local rulers in place and collect tribute, Ibn Tughluq tried to institute direct governance, a policy that provoked rebellions. Hindu rajas created an alliance to resist Delhi rule. By 1344 tribute payments in the Deccan were off 90 percent. An independent sultanate in the south, the Bahmani Sultanate, was formed in 1347 by Muslims who remained in the Deccan after Ibn Tughluq restored Delhi as the empire's capital. That same year Gujarat and Kathiawar revolted, uprisings that Ibn Tughluq success- fully suppressed.

In 1349 the Sammas, a group of Muslim chiefs, seized power from the Sumras. Both the Sumras and Sammas are thought to have origi- nally been Hindu Rajputs. Though they were now Muslims, they kept pre-Islamic names. Sammas territory encompassed Sind and parts of Baluchistan and Punjab, and its capital was Thatta. Ibn Tughluq set

off for the capital where the Sammas had given a rebel chief sanctuary. But during the expedition Ibn Tughluq took ill near Thatta and died in 1351.

With Ibn Tughluq's death no suitable descendant of Ala-ud-Din existed to take the throne. A group of nobles and religious leaders invited Firuz Tughluq (r. 1351-88), a cousin of Ibn Tughluq, to take the throne. He accepted the appointment, and one of his first acts was to withdraw the army from Sind. Firuz became known for his concern for his subjects and their welfare. Taxes were lowered and the empire's infrastructure repaired and expanded. Sind was now basically indepen- dent, though in a display of fealty rulers sent a prince to the Delhi court as a resident. In the decade after Firuz's death at age 80 in 1388, eight different Tughluq kings ruled the sultanate, which had seen its hold over the territories loosen during the Firuz reign. Mahmud Nasir-ud- Din Tughluq (r. 1395-98) was the last of the Tughluq sultans. During his reign the Gakkar chief Shaikha created an independent state in Punjab and for a time extended his territory to include Lahore. Nasir- ud-Din's rule ended when he was temporarily driven from Delhi by a new invader from Central Asia: Timur Lenk.

Timur and the Sayyid and Lodi Dynasties

During this time the power of the Mongols, like that of the sultanate, was weakening. By 1320 almost all the Mongols had been driven from their former stronghold in Transoxiana. In 1369 a Turkish chief, Timur (1336-1405), took power as the grand emir of Transoxiana. Son of a minor chief, as a young man he had received a leg wound that gave him a permanent limp, and he was called Timur Lenk (the lame), anglicized into Tamerlane. A devout Muslim, he sought to conquer all Mongol lands for Islam. But his ambitions were not limited to retaking Mongol holdings. After conquering lands in Persia and Russia, in 1397 he invaded the subcontinent. He took Delhi from Mahmud Tughluq in 1398 and sacked the city, then withdrew to his capital at Samarkand, modern Uzbekistan, from where he administered the territory.

Mahmud Tughluq returned to the throne of Delhi after Timur's departure and occupied it until his death in 1413. However, the Tughluq dynasty is considered to have ended with Timur's conquest of Delhi. During Mahmud's final years the sultanate continued to disinte- grate, and governors declared their independence.

By the end of the short-lived Sayyid dynasty (1414-51), which suc- ceeded the Tughluq dynasty, the sultanate's dominion was basically con- fined to Delhi and its immediate surroundings. During the rule of its last ruler, Alam Shah (r. 1444-51), Multan claimed independence, but the attempt by Multan's populace to name their own ruler was thwarted when a local Afghan chief, Rai Siphera, or Sarha Langa, staged a coup, founding the Langa dynasty of Multan, which survived for 80 years.

The last dynasty to rule the Delhi Sultanate was the Lodi dynasty (1451-1526). Bahlul Lodi (r. 1451-89) restored the sultanate's author- ity in much of the northern subcontinent. But Multan remained inde- pendent, despite Lodi's efforts to conquer it. He finally recognized its ruler, Hussain Langha (1456-1502), the son of Sarha Langa, under whom Multan expanded its territory.

Once again the Delhi Sultanate declined. But this time it would not recover. By about 1500 independent Muslim kingdoms had arisen in Multan, Gujarat, Malwa, Sind, and Khandesh, in central India. With the death of Ibrahiml Lodi (r. 1517-26) the Delhi Sultanate came to an end. It gave way to a kingdom that would be among the grandest the world had seen: the Mughal Empire.