Panchayati Raj: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Antyodaya Mission

Annual rankings

2019

SUBODH GHILDIYAL, Dec 14, 2019: The Times of India

From: SUBODH GHILDIYAL, Dec 14, 2019: The Times of India

Tamil Nadu’s Molugamboondi has topped the 2019 rankings of gram panchayats in the country, scoring high on implementation of development and infrastructure programmes under the Mission Antyodaya scheme.

The second rank has gone to Bambhaniya GP of Bhavnagar in Gujarat while four more Gujarat panchayats are tied for third ranking. One in Maharashtra, two each of Punjab and Tamil Nadu, and five Gujarat panchayats are tied at fourth ranking.

It marks a major change from the 2018 ranking table when 49 out of 50 gram panchayats in the top six rankings were from Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh, with one from Patan in Gujarat being the sole exception.

The national rankings under Mission Antyodaya are done to gauge the implementation of schemes across fields ranging from agriculture, roads, health parameters to poverty alleviation, rural housing, electrification, drinking water, PDS, education and poverty alleviation. While in 2017 and 2018, the villages were ranked on the basis of 46 parameters, the scale has been widened to 112 parameters for 2019.

Without any plan or budget of its own, Mission Antyodaya under Union rural development ministry is conceived as a convergence platform to bring about consolidated implementation of existing schemes to improve physical and social parameters in a panchayat. The progress made is measured at the end of the year through a survey which ranks them on a scale of 100.

According to a senior official, the 2019 rankings are provisional as the process of assessing the panchayats is still on. A total of 2.4 lakh panchayats are to be ranked, with around 2.1 lakh completed.

The top panchayat from Chhattisgarh is Mura in Raigarh while that from Andhra Pradesh is Inamadugu in SPSR Nellore, and from Karnataka it is Nandagad in Belagavi — all tied at fifth slot. Kerala figures first at the sixth slot with Athirampuzha panchayat in Kottayam district.

Meghalaya’s Jangnapara falling in South West Garo Hills figures at 7th slot, which it shares with 36 other panchayats.

As many as 269 panchayats from just 15 states are ranked in the top 10 places. Gujarat has the maximum entries with 99, followed by Punjab with 66, Kerala with 69 and Tamil Nadu with 21.

In contrast, large states like Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Telangana have just one panchayat each in top 10 places, while Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal have two panchayats each.

‘Best’ panchayats

2009-15

See graphic, 'Panchayat rankings, state-wise, 2009-10 and 2014-15'

2019: The Times of India's survey reveals otherwise

KARAL MARX & NIMESH KHAKHARIYA, TNN, Dec 21, 2019: The Times of India

From: KARAL MARX & NIMESH KHAKHARIYA, TNN, Dec 21, 2019: The Times of India

About three kilometres ahead of Molugampoondi (Tamil Nadu), the motorable road gets narrower. The ride is particularly bumpy as the village nears and potholes grow in both number and size. A man in his forties is standing outside a cemented house. “Is this Molugampoondi?” He nods and introduces himself as Sugumar. Asked how he feels about his area topping the 2019 rankings of gram panchayats in the country, he looks puzzled. “Have you seen the roads here? Even public buses don’t want to come. There is a private one that brings passengers twice a day,” he says.

Sugumar’s bafflement is shared by the TOI correspondent who set out to Molugampoondi in Tiruvannamalai district this week to see what the gram panchayat had done right to bag the top place in the country among 2.26 lakh gram panchayats ranked under the Mission Antyodaya scheme of the Union rural development ministry. (MoRD) The rankings are provisional as over 16,000 gram panchayats are still being evaluated.

The national rankings are done to gauge the implementation of schemes across fields ranging from agriculture, roads, health parameters to poverty alleviation, rural housing, electrification, drinking water, PDS and education. While in 2017 and 2018, the villages were ranked on the basis of 46 parameters, the scale was widened to 112 parameters for 2019.

In Molugampoondi gram panchayat — which scored full marks for roads, education, health and sanitation — TOI found garbage-strewn and potholed paths. Inhabited mostly by Dalit families, lack of maintenance had left a public toilet built by rural development and panchayati raj departments unusable and covered in vegetation. Several people were defecating in the open.

Gujarat’s Bambhaniya (Bhavnagar district) — ranked third in the country — didn’t have better roads either or a higher secondary school. The nearest primary health centre was six kilometres away. Najir Belim, a resident, said, “I don’t know why our village was rated high on facilities. Most families here don’t have pucca houses.” While the data submitted to Mission Antyodaya said that the village has an ATM and a bank branch, it has neither.

The stark difference between the rankings and the ground reality can partly be explained by the fact that the rankings were based on self-assessment. According to a video on the Mission Antyodaya website, “field level functionaries of any gram panchayat or village can provide details of facilities in their area on Mission Antyodaya app”. It added that answers to the state of facilities the staff seek can be procured from the panchayat secretary or an authorized person. The data that is collected can then be given to the gram sabha for validation before uploading it on the app.

But a disclaimer at the end of the ‘scorecard’ says that the uploaded data is yet to be verified by the gram sabha and that MoRD is not responsible for any discrepancy in the data reported.

Questioned by TOI, authorities in both gram panchayats admitted to the “mistake” in self-assessment. Former panchayat secretary V Gokul — who submitted data for Molugampoondi — tried to pin the blame on another functionary. And Ghanshyam Siyar, a former talati (accountant) who assessed Bambhaniya, said that the errors were made since the form he filled was in English, a language he does not understand.

Local administration in both places are now making amends. The director of District Rural Development Agency (DRDA) at Bhavnagar added that a final survey would be done to give the correct score while Tiruvannamalai district collector K S Kandasamy said that an inquiry has been ordered into the matter and the ranking would be revised. Additional chief secretary Hans Raj Verma, Tamil Nadu Rural Development and Panchayati Raj, could not be reached for comment.

Meanwhile, residents in both gram panchayats are hopeful that now that their villages are in the spotlight, things might change for the better. “My son has to cross a river to go to school. I wish our dream for a high school here becomes a reality soon,” said a 45-year-old resident in Molugampoondi.

Development by Panchayats

2017: The 83 best

Subodh Ghildiyal, Just 7 Figure In List Of 83, December 22, 2017: The Times of India

From: Subodh Ghildiyal, Just 7 Figure In List Of 83, December 22, 2017: The Times of India

Just seven gram panchayats from north India figure among the top 83 panchayats on development index, in a bunch that is overwhelmingly crowded by southern states led by Andhra Pradesh.

Tellapur gram panchayat in Sangareddy district of Telangana has been found to be the best village in the country followed by Parapatla in Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh. Cheedikada in Vishakhapatnam is ranked 3rd, Kajuluru (East Godavari), Unguturu (Krishna) and Eguva Thavanampalle (Chittoor) in AP, are ranked 4th, and Koujalagi in Belagavi in Karnataka and Indupalli in Krishna in AP, are ranked 5th .

Crucially, the most developed panchayats include 33 from Andhra Pradesh, 21 in Tamil Nadu, six in Kerala, five from Maharashtra and Karnataka each, and four from Telangana.

The first-ever ranking of villages forms part of the “baseline survey” done by Union rural development ministry among 50,000 gram panchayats that the “Antyodaya” scheme aims to turn “poverty free”.

In what shows a skewed picture of development across the country, only seven panchayats from northern states figure in the privileged list of 83 GPs ranked up to 10th .

The northern villages in the list are Barwasani in Sonepat in Haryana (rank 6), Usmanpur in Nawanshahr (ranked 7), Jadla and Kahma villages in Nawanshahr (ranked 8), Mana Singh Wala in Ferozepur and Naranwali in Gurdaspur, all in Punjab, and Pandaul (east) in Madhubani in Bihar (rank 10th ).

In sharp contrast, Andhra and Tamil Nadu have the most villages with overall development. Crucially, Gujarat figures nowhere in the list of 83 villages ranked from top to 10th .

Interestingly, it is coastal Andhra which seems to have the most developed countryside. The rankings are based on the parameters of infrastructure, economic development and livelihoods, health and sanitation, women’s empowerment and financial inclusion.

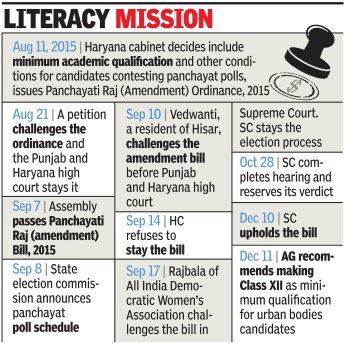

Education criteria for elections

SC upholds minimum education criteria s

The Times of India, Dec 11 2015

AmitAnand Choudhary SC upholds law fixing edu criteria for panchayat polls

In a landmark verdict, the Supreme Court upheld the Haryana government's law mandating minimum educational qualifications as a prerequisite for contestants in panchayat polls. A bench of Justices J Chelameswar and Abhay Manohar Sapre said education is an essential tool for a bright future and plays an important role in the development and progress of the country and elected representatives must have some educational background to enable them to effectively carry out their duties.

This is the first time that the court has upheld that minimum educational criteria can be fixed for candidates and illiterates debarred from the electoral arena. The order validates a similar law passed by Rajasthan, the first state to do so. The apex court rejected a bunch of petitions filed by some women contestants challenging the validity of the law mandating educational qualifications -Class 10 pass for men, Class 8 pass for women and Class 5 pass for Dalits -for contesting panchayat polls Haryana. The law also disqualifies those who don't have toilets at home and had not repaid agricultural loans or defaulted on electricity bills and other arrears to government authorities. The court upheld the law despite noting that a major chunk of the people would be disqualified from contesting the polls. More than 83% of rural wom en above 20 years and almost 67% of women in urban areas are likely to be disqualified under the law while 68% of the SC women and 41% of SC men would be ineligi ble. In a big boost to the NDA's sanitation drive, it also ruled that Haryana's decision to bar candidates without toilets at home from contesting panchayat polls is a “good decision“.

A critique of the Rajasthan and Haryana laws

The Times of India Dec 20 2015

Rema Nagarajan

About 90% of women and 95% of Dalit and tribal women in Rajasthan can't become sarpanch or zilla parishad members as they are not educated enough. And yet they're eligible to become an MP, minister or even PM.

Haryana has a similar law that's been upheld by SC I magine a law that bars over 94% of women of eligible age from contesting a local election in a democracy . Or, one that bars almost 97% of Dalit and tribal women from contesting for a public office.Strange as that sounds, that's exactly what a law passed by the Rajasthan government has done.Similarly , in Haryana, the government has passed a law that has made almost 70% of its women unfit to contest. And this law has been upheld by the highest court.

If this large a proportion of the population being excluded from contesting for the posts of sarpanch, or zilla parishad or panchayat samiti posts seems alarming in a democracy , then a closer look at the data from the 2011 census on age group-wise educational qualifications for different communities in each state reveals an even more worrying picture of extreme exclusion of Dalits and tribals, especially women in these communities, who are doubly damned. The biggest irony is that every one of those being excluded from these local elections would be eligible to be a Member of Parliament or even the Prime Minister of the country as no educational qualifications are necessary for these posts.

Anyone contesting for these panchayat posts has to be above 21 years. But only a small fraction of those contesting these elections would be in their 20s, especially among women. Across all communities, the higher the age group, the lower the average educational level and, hence, the lower the proportion of people who can contest.

Thus, in Haryana, among all women above 20 years, 68.4% would be ineligible. However, if we were to consider women aged 40 or more, over 90% would be excluded including among Dalit women, for whom the educational cut-off is lower -class 5 -against the class 8 cut-off for others. Among Dalit men, for whom the educational requirement is class 8 pass, 70% of those aged 35 or more would be excluded.

In Rajasthan, the picture is even more dismal in the non-scheduled areas. (In scheduled areas, the minimum qualification to contest for a sarpanch's post is lower, at class 5.) To contest for a zilla parishad post, one has to have a minimum qualification of class 10 pass. That excludes 86% of the overall population and 94% of women in the state.Among men and women aged 50 and above, 90% and 99% respectively, are now barred.

When it comes to the post of sarpanch, the educational cut off is completion of middle school or class 8 pass in Rajasthan. This means that three-quarters of the men aged 40 and above and over 95% of women aged 35 or more are disqualified. Among Dalits, this criteria leads to exclusion of 99% of 40-plus women and over 80% of 35-plus men. In rural Rajasthan, the literacy rate is about 76% for men and 46% for women. Literacy being merely the ability to read and write, the proportion of those who have completed primary or any higher level is extremely low, especially among those over 20 years of age.

Several activists point out the unfairness of penalizing an older generation that had little or no access to education, adding that it is their great knowledge and experience of local needs and circumstances that has made so many of them such outstanding perform ers in their panchayats.

“Our case challenging the con stitutionality of the Rajasthan law is pending in the high court. Bu with the Supreme Court judgment in the Haryana law case, we have lost all hope. In one fell swoop, large sections of the population have been put out of the race.Their democratic rights are being attacked and this will spread to other states. The worst affected will be women and other weaker sections. Since the right to educa tion came up, has the government managed to fulfil its obligation? If they did not, what right do they have to bring in such a law?“ asked Satish Kumar of the Centre for Dalit Rights in Rajasthan.

Incidentally , the level of education is just one of the criteria for exclusion in the two states. They have additional criteria for exclusion such as a two-child norm, functional toilet at home, and no pending power bills or loan payments. If these criteria are also taken into account, the exclusions would be even bigger and would be from among the poorest and most disadvantaged communities.

While Panchayati Raj was supposed to be an exercise in deepening democracy, these extremely high exclusions at the grassroots, especially of the most disadvantaged, seem to be moving rural Haryana and Rajasthan towards a plutocracy , defined as a society ruled or controlled by a small minority of the wealthiest citizens.

Infrastructure

Computers: as in 2021

Dec 30, 2022: The Times of India

From: Dec 30, 2022: The Times of India

See graphic:

Panchayats with and without computers, presumably as in 2021

As part of its Digital India push, the government is implementing the BharatNet project to connect all gram panchayats by broadband. The deadline to complete the project is August 2023. However, of India’s more than 2. 7 lakh gram panchayats and traditional local bodies, one in every five still does not have a computer. While Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh are the worst off, even the likes of Haryana and Telangana – home to IT hubs at Gurugram and Hyderabad, respectively – don’t have computers in over half of their gram panchayats, according to information shared by the Panchayati Raj ministry in Parliament.

Family planning/ two-child norm for candidature

2-child norm valid even if 3rd given for adoption: SC

Dhananjay Mahapatra, October 25, 2018: The Times of India

‘If 3rd Kid Is Born, Candidate Can’t Fight Rural Polls’

The Supreme Court ruled that birth of a third child would automatically disqualify a person from contesting panchayat polls and from holding the post of a member or sarpanch in a panchayat.

Scotching attempts by a tribal sarpanch in Odisha to step around the disqualification law by giving away one of his three children in adoption to comply with the two-child norm, a bench of Chief Justice Ranjan Gogoi and Justices S K Kaul and K M Joseph said the legislative intent in Panchayati Raj Act was to bar any person having three ‘live births’ in her/his family from contesting panchayat elections or holding posts in panchayats.

“The legislative intent is to restrict the number of births in a family and not on the basis of benefit available under the Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act in regulating the number of children by giving the excess children in adoption,” the CJIled bench said.

The petitioner, Minasingh Majhi, had challenged an Orissa high court decision to disqualify him from holding the sarpanch’s post in a panchayat in Nuapada district after the birth of his third child. Two children were born to him and his wife in 1995 and 1998. He was elected sarpanch in February 2002, but the birth of the third child in August 2002 led to his disqualification from the post.

His counsel Puneet Jain argued that he had given the first born in adoption in September 1999 and as Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act provides that once a child is given in adoption, that child ceases to be a member of the original family, his client remained compliant with the two-child norm to hold the post of sarpanch.

Jain argued that though Majhi was the biological father of three children, legally he had two children as the first born was given away in adoption to another family and, hence, he was compliant with the norm set by the Odisha Gram Panchayat Raj Act.

The bench said, “We do not know whether the law intended to make panchayat members and sarpanchs the role model for entire India by fastening the two-child norm on them. But the legislative intent appears clear that it wanted to put a cap on the number of children at two for those holding elected posts in panchayats.”

Jain argued that twins and triplets were born to persons and asked whether they should be disqualified from contesting panchayat elections or holding elected posts in the grassroots level democratic institution? The bench said the situation did not apply to the case in hand and clarified that birth of twins and triplets was a rare phenomenon and the court would take an appropriate decision when such a case was brought before it.

An SC bench of CJI Ranjan Gogoi and Justices S K Kaul and K M Joseph said the legislative intent in Panchayati Raj Act was to bar any person having three ‘live births’ in his family from contesting panchayat elections or holding any post

Rules

Rajasthan: women sarpanches lose post If kin interfere

If kin interfere, women sarpanch to lose post, June 4, 2020: The Times of India

The panchayati raj department in Rajasthan has issued an order stating that if any interference by a husband or relatives is noticed in the functioning of a woman public representative (sarpanch) or is seen to be performing her duties, without objection from her, then strict action would be taken against her under Section 38 of the Panchayati Raj Act, leading to her suspension or removal. Action will be taken against the husband/relatives also.

The order states that government officials found encouraging such interference too shall be punished. “It has been brought to the notice of the state government that in a few cases in panchayati raj bodies, instead of the elected woman representative (sarpanch), her husband, relatives, someone closely related or any other person is performing her office duties or participating in a meeting directly/indirectly or interfering in her work,” read a letter written to the collectors, chief executive officers of zila parishads and block development officers by Rajeshwar Singh, ACS, rural development and panchayati raj department. “Such an act falls in the category of misconduct in discharging one’s duty and incapability by the elected member/office-bearer. If such a case is found in any of the panchayati raj institutions, action will be taken against the woman member/officebearer concerned under Section 38 of the Panchayati Raj Act, (leading to her suspension or removal),” it added.

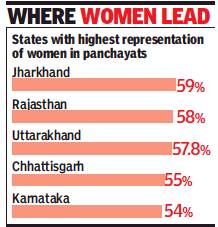

Women: representation of

The position in 2008, 2016

From: Radheshyam Jadhav, 25 yrs later, route from panchayat to Parliament still blocked by patriarchy, December 10, 2017: The Times of India

On Women’s Day in 2017, Ramilaben Gamit, a member of the Taparwada gram panchayat in Gujarat’s Tapi district, received the Swachh Shakti Puraskar from PM Narendra Modi for making her village free of open defecation. So when the election dates were announced, she was sure a party would offer a ticket but nothing came her way.

Twenty-five years after Constitutional amendments were passed to reserve one-third seats for women in panchayati raj institutions in December 1992, data shows it’s unlikely that women like Ramilaben will ever fulfill their dream of making it big in politics. Most of the 13.45 lakh elected women representatives in panchayati raj institutions, comprising 46% of the elected grassroots leaders, acquit themselves well as leaders, but never get to state assemblies or Parliament. In fact, only 11 of 64 women MPs have worked at the grassroots level in the panchayat system. A study commissioned by the Maharashtra election commission has recommended guidelines directing parties to give 5% of the tickets in an unreserved constituency to women.

The study, conducted last year by Pune-based Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics, found that 86% of women said they contested zilla parishad or panchayat samiti elections only because the seat was reserved for a woman. At the same time, 73% said they wanted to contest a second time. The survey found proxy women members who contested because they belonged to a political family, but there were also women without a political background who wanted to make it big in politics, said Manasi Phadke, the project coordinator. The panchayati raj ministry’s 2008 study drew similar conclusions.

It said that women representatives had low prior association with politics, and for most women the act of contesting an election signalled their entry into active politics. This study found that 90% of women candidates contested panchayat polls at the ward level for the first time, only 7.9% jumped into the fray a second term, and a mere 1.4% contested for a third term.

Women:'Reservation’ for

Tamil Nadu: 50% quota

The Times of India, Feb 21, 2016

Jaya's parting gift to women: 50% seats in all local bodies

B Sivakumar

Focusing on women empowerment ahead of the state election, the Tamil Nadu assembly passed two bills guaranteeing 50% reservation for women in all local bodies in the state. The bills were introduced to make necessary amendments to Tamil Nadu Panchayats Act, 1994 and various City Municipal Corporation Acts to increase reservation for women from the present 33%. The state is slated to have local body polls in October this year.

Tamil Nadu, which has a relatively better sex ratio of 995 women for 1,000 men, is the 17th state to provide 50% representation for women in local bodies. Some states have provided 50% reservation for women in rural local bodies, but not in urban bodies like municipalities and corporations.

The Centre is considering an amendment to the Panchayati Raj Act to introduce 50% reservation for women in all urban local bodies across the country . Members of key opposition parties - DMDK, DMK and PMK - were not present in the House when the legislation was put to vote.

The parties have been boycotting the session protesting against what they call denial of democratic rights to opposition members to express their views in the assembly .

As in 2018, Rajasthan: women sarpanches lose post If kin interfere/ 2020

June 6, 2020: The Times of India

From: June 6, 2020: The Times of India

The panchayati raj department in Rajasthan has issued an order stating that if any interference by a husband or relatives is noticed in the functioning of a woman public representative (sarpanch) or is seen to be performing her duties, without objection from her, then strict action would be taken against her under Section 38 of the Panchayati Raj Act. This will lead to her suspension or removal. Action will be also be taken against the husband or relatives.

The order states that government officials found encouraging such interference too shall be punished. “It has been brought to the notice of the state government that in a few cases in panchayati raj bodies, instead of the elected sarpanch, her husband, relatives, someone closely related or any other person is performing her office duties or participating in a meeting directly/indirectly or interfering in her work,” reads a letter written to the collectors, chief executive officers of zila parishads and block development officers (BDOs) by Rajeshwar Singh, ACS, rural development and panchayati raj department.

Why the order?

It all started on April 10, when Leena Kanwar, the sarpanch of Palada village in Rajasthan’s Nagaur district was suspended after her husband was found holding official meetings. Later in May, Rajasthan high court revoked the suspension calling it “harsh” and directed the state government to ensure such an act was not repeated in future. According to the chief executive officer (CEO) of Nagaur zilla parishad, Jawahar Choudhary, “Leena Kanwar was suspended after her husband held a meeting with a few government officials on Covid-19 issue. It also appeared that he even admonished the officials. Later, she challenged it in the HC saying she was new to the post and was not aware of the norms. She has been reinstated now.” What's interesting? This is not the first time such a order has been given. A senior panchayati raj department official said, “The order on account of the Nagaur case. But it has been re-issued several times since 2010.”

What it says

- Rajasthan’s Panchayati Raj dept order promises strict action against women sarpanches letting husbands or relatives ‘perform’ her duties

- Action will be taken under Section 38 of the Panchayati Raj Act, leading to her suspension or removal

- Government officials found encouraging such interference too shall be punished

- District-level officers asked to take action against elected member and employees/officials as per directions and inform dept

“Such an act falls in the category of misconduct in discharging one’s duty and incapability by the elected member/office-bearer. If such a case is found in any of the panchayati raj institutions, action will be taken against the woman member/office-bearer concerned under Section 38 of the Panchayati Raj Act, (leading to her suspension or removal),” it added.

It also asked district-level officers to take action against the elected member and the employees/officials as per directions and inform the department. Meanwhile, a panchayati raj official said, “If she doesn’t resist or objects to such an action by her husband or relatives, only then will action be taken against her. However, if she is under pressure from the husband/relatives, she can lodge a written complaint with the police or the higher authorities of the department.” “This order is very biased. With the kind of male dominance that we have, to punish and criminalise an act for which the woman doesn’t have complete agency, is horrifying. We all know violence is used against women many a time to get things done. So, instead of counselling her, taking action against the woman is ridiculous. Government should end patriarchy before doing this,” said Kavita Srivastava of People’s Union for Civil Liberties.

“Also, men are all the time taking all kinds of support. Why no action against them? Public consultation should have happened. What warranted such an order should have been shared. Instead of promoting and nurturing women’s autonomy, they are using punishment. This is harsh and an attempt to weaken women within the institution by putting the entire onus on her. This will be misused and the stick will be used to manipulate her,” she added.

This order is very biased. Violence is used against women many a times to get things done. So, instead of counselling her, taking action against the woman is ridiculous. Government should end patriarchy before doing this

Challenges Rajasthan's women sarpanches face

While reservation can be an important impetus to women‘s empowerment, it is not a guarantee for participation of the elected women. A study in Rajasthan — the first state to enact the Panchayat Act in 1953 and that has 70,527 women elected representatives — found that women were actively prevented from participating in panchayat activities by male family members and other members of the panchayat itself.

Though 56.49% of the elected representatives in the state are women — the highest in the country — male members often insisted on attending meetings in place of them. They took advantage of the low levels of literacy and lack of knowledge and experience to take decisions and tried to keep them out of important meetings, said the study by International Journal of Science and Research. Many elected women complained that their suggestions were not considered seriously nor were they consulted while decisions were being made. Some felt that their views were ignored only because they are women.

What women needed was support from the beginning of the election process and through the tenure of the elected representatives. This, the study said, would create an enabling environment for the recognition of women as leaders and the elimination of proxy candidates.