Pasi, Pasa

Contents[hide] |

Pasi, Pasa

This section has been extracted from THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all posts in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

Origin

A Dravidian caste of Behar, whose original occupation is believed to have been the tapping of the palmyra, date, and other palm trees for their sap. The name Pasi is usually derived from pasa, a noose or cord, which Mr. Nesfield interprets as disclosing that they have only recently emerged from the hunting state. It seems, however, more probable that the name refers, not to the snaring of wild animals, but to the sling or noose used by Pasis in climbing palm trees.

Internal structure

Pasis are divided into four sub-castes-Baydha, Ga id uha, Kamani, and Tirsulia. There are also Mahom¬by the desiguation Turk. The Byadha. sub-caste say that their original occupation was to collect the water-chestnut or singbani (Trapa bispinosa, Roxb.), but now they tap date trees like the otber sub-castes. '1'here is only one section, Kasyapa, which has been borrowed from the Brahmanical system ill comparatively recent times, and has no bearing on the regulation of marriages. Prohibited degrees are reckoned by the standard formula mamedl, chache1'a, etc., calculated to seven gener¬ations in the descending line.

Marriage

Pasis marry their daughters as infants or as adults according to their means, the former practice deemed the more respect¬able. The marriage ceremony is of the ordinary low-caste type. It is preceded by lagan, when a Brahman stirs up in water two grains of rice, representing the bride and bridegroom, and sprinkles vermilion over them as soon as the grains float into contact with each other. This favourable omen having been observed and a trifling sum paid as bride-price, a date for the marriage is fixed. The binding portion of the ceremony is the smearing of vermilion on the bride's forehead with the bridegroom's left hand. Opinions differ as to the practice of the caste in the matter of polygamy. Some say that a man may have as many wives as he can afford to maintain; others that he can only take a second wife with the consent of his first wife, and for the purpose of obtaining offspring. A widow may marry again by the sagai form, but is expected to marry her deceased husband's younger brother if there is one. Failing him, she may marry anyone not within the prohibited degrees. Divorce is effected, by the consent of the panchayat, when a woman is convicted of adultery with another member of the caste. Women divorced on these grounds may marry again on paying a fine, which usually takes the form of a feast to the caste panchciyat. Adultery with an outsider admits of no such atonement, and a woman detected in this offence is turned out of the caste, and usually becomes a regular prostitute.

Succession

In matters of inheritanoe the caste professes to be guided by the principles of the Mitakshara. law, which are enforced in oases of dispute by the caste-council (panchayat). Daughters, however, and daughters' sons, do not inherit so long as any deadi relatiye survives.

Religion

Most Pasis belong to the Sakta sect of Hindus, and regard Bhagavati as the goddess whom they are chiefly bound to worship. In their religious and ceremonial observances the Kamani sub-caste alone employ Tirhutia Brahmans, who are said to inour no sooial degradation by serving them. The other sub-oastes oall in degraded (patit) Brahmans for marriges only. Such Brahmans rank very low in social reputation, and their employment by the Pasis seems to be a reform introduced at a very recent date, for in all funeral ceremonies and at sacrifices offered to the greater gods whenever the servioes of a Brahman are not available the worshipper's sister's son (blui'l1Jd) performs the functions of the priest. Among the Pa.sis of Monghyr this ancient custom, whioh admits of being plausibly interpreted as a survival of female kinship, still prevails in such force that the caste has not yet been convinced of type necessity of engaging Brahmans at all. The guru of the Pasis is usually a Nanak-Shahi ascetic. The minor gods of the Pasis are very numerous. Bandi, Goraiya, Sokha, Sambhunath, Mahcimaya, Ram 'l'hakur, Mian Kabutra, Naika Gosain, Masan, Ostad, and Kartar are the names mentioned in different parts of Behar. Goats, pigeons, cakes, milk, etc., are offered to them six times in the year, the offerings being afterwards eaten by the worshippers. In the month of J eth the sickle (hansuli) used for cutting the palm tree is set up and solemnly worshipped with o:fferings of flowers and grain.

Social status and occupation

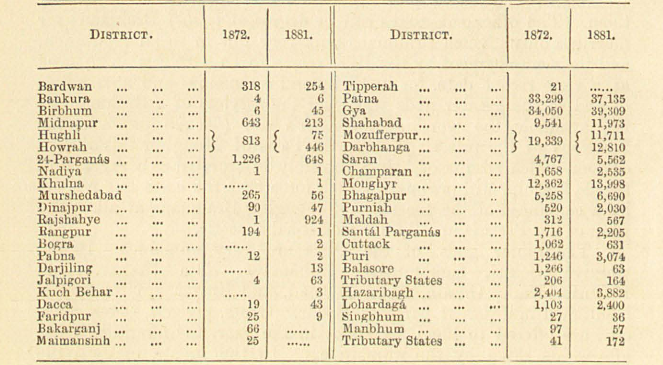

Pasis rank socially below Tatwas, and on much the same level as Binds and Chains, except that, unlike these, they nowhere attain to such consider¬ ation that Brahmans will take water from theil: hands. Most of them eat fowls aDd field-rats, and indulge freely in spirituous and fermented liquors. Many of them have taken to cultivation instead of, or in addition to, their traditional avocation, and hold laDd as ocoupancy or non-occupancy raiyats. Others are employed as day-labourers, porters, coolies, or servants to low-caste shop-keepers. In Bengal there is comparatively little demand for their services as palm-tappers, for the owners of toddy and date palms either extraot the juice themselves or employ Bhuin¬malis to do so, and shops for the sale of spirituous liquors are usually owned by SUUl'is or uutcaste Sudras. Aocording to VI'. Wise, the extraotion of the juice of the tat, or palmyra palm, as well as that of the khaJur, or date palm, is a most importaut operation in Eastern Bengal, although it has not given rise to the formation of a special caste. 'l'he tal trees are tapped from March to May; the date palms in the cold season. The juice of the former, or toddy (tari ), is used in the manufacture of bread; and as an intoxicating liquor by adding sugar and grains of rice. Hindustani dl'Unkards often add dlud uTa to increase its intoxicating properties. In Dacca a tal grove is usually rented, and on an average twelve annas a tree are obtained. The quantity of juice extracted varies from an average of five to ten pounds. When fresh this sells for two annas a seer, but if a day old for only one anna. Date palm ta?'{ is rarely drunk, being popularly believed to cause rheumatism, but is extensively used in preparing sugar. A date palm is generally leased for seven annas a year. The following statement shows the number and distribution of Pasis in 1872 and 1811 :¬