Patiala State, 1908

Contents |

Patiala State, 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

The largest in area, wealth, and population of the

three Phulkian States, Punjab, and the most populous of all the Native

States in the Province, though second to Bahawalpur in area. It lies

mainly in the eastern plains of the Punjab, which form part of the

great natural division called the Indo-Gangetic Plain West ; but its

territories are somewhat scattered, as, owing to historical causes, it

comprises a portion of the Simla Hills and the Narnaul ilaka, which

now constitutes the nizamat of Mohindargarh, in the extreme south-east

on the borders of Jaipur and Alwar States in Rajputana.

The territory is interspersed with small tracts or even single villages belonging to the States of Nabha, Jlnd, and Maler Kotla, and to the British Districts of Ludhiana, Ferozepore, and Karnal, while, on the other hand, it includes several detached villages or groups of villages which lie within the natural borders of those States and Districts.

Its scattered nature makes it impossible to describe its boundaries clearly and succinctly, but briefly it may be described as consisting of three portions. The main portion, lying between 29 23' and 30 55' N. and 744o'and 76 59' E., and comprising the plains portion of the State west of the Jumna valley and south of the Sutlej, is bordered on the north by the Districts of Ludhiana and Ferozepore; on the east by Karnal and Ambala ; on the south by the State of Jlnd and Hissar District; and on the west by Hissar.This portion forms a rough paralldo-gram, 139 miles in length from east west, and 125 miles from north to south, with an appendage on the south lying south of the Ghaggar river and forming part of the nizamat of Karmgarh.The second block lies in the Siwalik Hills, between 3o 4o'and 31 1o N. and 76 49 and 77 19' E.

It is bordered on the north by the Hill States of Bhagal, Dhami, and

Bhajji ; on the east by those of Koti, Keonthal, and Sirmur ; on the

south by Ambala District ; and on the west by the States of Nala-

garh and Mailog, and by Ambala District. This portion is 36 miles

from north to south, and 29 miles from east to west, and forms a

part of the nizamat of Pinjaur.The third block, the nizamatof

Mohindargarh, lies between 27 47' and 28 28' N. and 75 56' and

76 i7'E., and is entirely surrounded by Native States Jind to the

north, Alwar and Nsbha to the east, and Jaipur to the south and west.

It is 45 miles from north to south, and 22 miles from east to west.

physical aspects

No great river flows through the State or along its borders, the chief stream being the Ghaggar, which runs in an ill-defined bed from the north-east of its Main portion south-west through the Pawadh to the Bangar and thence in a more westerly direction, separating the Pawadh from the Bangar (Narwana tahsil), after which it leaves Patiala territory. The other streams are mere seasonal torrents. They include the Sirhind Choa or stream which enters the State near Sirhind and traverses the Fatehgarh, Bhawanigarh, and Sunam tahsils, following probably the alignment of the canal cut by Firoz Shah III about 1361. South of this through the Bhawanigarh and Karmgarh tahsil flows the Jhambowali Choi, and the Patialewali NadI, which passes the capital.

Both fall into the Ghaggar. There are minor streams in the Pinjaur tahsiland the Mohindargarh nizamat. In the former alone are there any hills of importance, the rest of the State being a level plaln. Geologically, the State may be divided into the Patiala Siwaliks, composed entirely of Tertiary and principally of Upper Tertiary deposits ; the Aravalli outliers in Mohindargarh : and the portion which lies in the Indo-Gangetic alluvium.

Botanically, the State includes a large portion of the Eastern Punjab, belonging partly to the upper Gangetic plaln, and partly to the desert area ; the territories of Narnaul, &c., in north-eastern Rajputana, with a desert flora ; and a tract near Simla in the Outer Himalayas, whose flora is practically that described in the Flora Simtensis. The klkar (Acacia Arabica) which grows abundantly in the Pawadh dnd Dun, is used for all agricultural purposes. The beri (Zizyphus Jujuba) is planted near wells and in fields, and in the Mohindargarh nizamatand at Sunam, Samana, and Rawaur in gardens. Banur and Sirhind, the eastern parts of the Pawadh, are noted for their mangoes. The pipal (Ficus religiosa), barota (Ficus indicd), and nim (Melia Azadirachta) are planted close to wells and ponds near villages. The shisham (Dalbergia Sissoo) is planted in avenues along the canals, and siras (Albizzia LebbeK) on the road-sides. The frans (Tamarix orientalis) common near villages, is used for roofing. The dhdk (Butea frondosd) is found in marshy lands and btrs (reserves). The jand (Prosopis spicigera), kikar, reru, and jal are common in the Jangal, Bangar, and Mohindargarh. The khair (Acacia Catechu) and gugal(Balsamodendron Mukut) are common in the Mohindargarh nizamat, and the khajur (Phoenix dactylifera) in Pinjaur, Dun, and in the Bet (Fatehgarh tahsil). Chltal (spotted deer), charkh, kakar (barking-deer), musk deer, gural, and leopard are common in the hills ; and the following mam- mals are found throughout the State : wolf, jackal, fox, wild cat, otter (in the Bet), wild hog (in the birs), antelope, nilgai (in the birs Bet, Narwana, and Mohindargarh), monkeys (in the Narwana tahsil) and gazelle (chinkara).

Game-birds include peafowl, partridges (black and grey), quail, lapwing, chikor, and phearawt (in the hills). The crane, snipe, green pigeon, goose, and rawd-grouse are all seasonal visitors. Among venomous snakes are the cobra, chitkabra or kauridla (found every- where), dhdinan, ragadbans, and padina (in the Mohindargarh nizamat).

The healthiest parts of the State are the Bangar and Jangal tracts and the Mohindargarh nizamat. The Bet and the thanas of Ghuram Ghanaur and Banur are very unhealthy, consisting largely of swamps. In the Pawadh, where there is no marsh-land, the general health is fair. The climate of the hills is excellent, except in the Pinjaur thana. In the Pinjaur hills the winter is cold, and the rainy season begins some- what earlier than in the plalns, while in summer the heat is moderate. In the Jangal tract and the Mohindargarh nizamat the heat is intense in the kot season, which begins early, and the air is dry all the year round. But if the sky is clear the nights are generally cool.

The rainfall, like the temperature, varies considerably in different parts of the State. About Pinjaur and Kalka at the foot of the Simla Hills it averages 40 inches, but decreases away from the Himalayas, being probably 30 inches at Sirhind, 25 at Patiala and Pail, 20 at Bhawanigarh, and only 12 or 13 at Bhatinda and in the Mohindargarh nisamat. In the south-west the rainfall is not only less in amount, but more capricious than in the north and east. Fortunately the zone of insufficient rainfall is now for the most part protected by the Sirhind Canal, but Mohindargarh is still liable to severe and frequent droughts.

Patiala town lies in a depression, and there were disastrous floods in 1852, 1887, and 1888. The greatest achievement of the State Public Works department has been the construction of protective works, which have secured the town from the possibility of such calamities in future.

history

The earlier history of Patiala is that of the PHULKIAN STATES. Its history as a separate power nominally dates from 1762, in which year Ahmad Shah Durrani conferred the title of Raja Upon Ala Singh, its chief; but it may be more justly regarded as dating from 1763, when the Sikh confederation took the fortress of Sirhind from Ahmad Shah's governor, and proceeded to partition the old Mughal province of Sirhind. In this partition Sirhind itself, with its surrounding country, fell to Raja Ala Singh. That ruler died in 1765, and was succeeded by his grandson Amar Singh, whose half-brother Himmat Singh also lald clalm to the throne, and after a contest was allowed to retain possession of the Bhawanigarh pargana. In the following year Raja Amar Singh conquered Pail and Isru from Maler Kotla, but the latter place was subsequently made over to Jassa Singh Ahluwalia. In 1767 Amar Singh met Ahmad Shah on his last invasion of India at Karabawana, and received the title of Raja-i-Rajgan. After Ahmad Shah's departure Amar Singh took Tibba from Maler Kotla, and compelled the sons of Jamal Khan to effect a peace which reMained unbroken for many years. He next sent a force under his general Bakhshi Lakhna to reduce Pinjaur, which had been seized by Gharlb Das of Mani Majra, and in alliance with the Rajas of Hindiir, Kahlur, and Sirmur captured it. He then invaded the territory of Kot Kapura, but its chief Jodh having been slaln in an ambush, he retired without further aggression. His next expedition was against the Bhattis, but in this he met with scant success; and the conduct of the campaign was left to the chief of Nabha, while Amar Singh turned his arms against the fortress of Govindgarh, which commanded the town of Bhatinda. After a long struggle it was taken in 1771. Soon after this Himmat Singh seized his opportunity and got possession of Patiala itself, but he was induced to surrender it, and died in 1774. In that year a quarrel broke out between Jind and Nabha, which resulted in the acquisition of Rawgrur by Jind from Nabha, Patiala intervening to prevent Jind from retaining Amloh and Bhadson also. Amar Singh next proceeded to attack Saifabad, a fortress only 4 miles from Patiala, which he took with the assistance of Sirmur. In return for this aid, he visited that State and helped its ruler Jagat Parkash to suppress a rebellion. In a new campaign in the Bhatti country he defeated their chiefs at Begran, took Fatehabad and Sirsa, and invested Rania, but was called on to repel the attack made on Jind by the Muhammadan governor of Hansi. For this purpose he dispatched Nami Mal, his Diwan, with a strong force, which after defeating the governor of liansi overran Hansi and Hissar, and Rania fell soon after. ut the Mughal govern- ment under Najaf Khan, its minister, made a last effort to regain the lost districts. At the head of the imperial troops, he seized Karnal and part of Rohtak; and the Raja of Patiala, though aided for a consideration by Zabita Khan Rohilla, met Najaf Khan at Jind and amicably surrendered Hansi, Hissar, and Rohtak, retaining Fatehabad, Rania, and Sirsa as fiefs of the empire. The wisdom of this moderation was evident. In 1777 Amar Singh overran the Farldkot and Kot Kapura districts, but did not attempt to annex them, and his newly- acquired territories taxed his resources to the utmost. Nevertheless, in 1778 he harried the Mani Majra territory and reduced Gharib Das to submission. Thence he marehed on Sialba, where he was severely defeated by its chief and a strong Sikh coalition. To retrieve this disaster Amar Singh formed a stronger confederacy, enticed away the Sialba troops by offers of higher pay, and at length secured the sub- mission of the chief without bloodshed. In 1779 the Mughal forces marehed on Karnal, Desu Singh, Bhai of Kaithal, being in alliance with them, and hoping by their aid to crush Patiala j but the Delhi minister found it more profitable to plunder the Bhai, and the Sikhs then united to oppose his advance. He reached Kuhram, but then retreated, in fear of the powerful forces arrayed against him.

In 1781 Amar Singh died of dropsy, and was succeeded by his son Sahib Singh, then a child of six. Diwan Nanu Mal, an Agarwal Bania of Sunam, became Wazir and coped successfully with three distinct rebellions headed by relatives of the Raja. In 1783 occurred a great famine which disorganized the State. Eventually Nanu Mal was compelled to call in the Marathas, who aided him to recover Banur and other places; but in 1788 they compelled him to pay blackmall, and in 1790, though he had been successful against the other enemies of Patiala, he could not prevent them from marehing to Suhlar, 2 miles from Patiala itself. Saifabad had been placed in their hands, and Nanu MaPs fall from power quickly followed. With him fell Rani Rajindar, cousin of Amar Singh, a woman of great ability and Nanu MaPs chief supporter, who had induced the Marathas to retire and visited Muttra to negotiate terms with Sindhia in person. Sahib Singh, now aged fourteen, took the reins of state into his own hands, appointing his sister Sahib Kaur to be chief minister. In 1794 the Marathas again advanced on Patiala, but Sahib Kaur defeated them and dr.ove them back on Karnal. In this year Bedi Sahib Singh attacked Maler Kotla and had to be bought off by Patiala. In 1798 the Bedi attacked Raikot, and, though opposed by the Phulkian chiefs, compelled its ruler to call in George Thomas, who advanced on Ludhiana, where the Bedi had invested the fort, and compelled him to raise the siege. Thomas then retired to Hansi ; but taking advantage of the absence of the Sifch chiefs at Lahore, where they had assembled to oppose the invasion of Shah Zaman, he again advanced and lald siege to Jind. On this the Phulkian chiefs hastened back to the relief of Jind and compelled Thomas to raise the siege, but were in turn defeated by him. They then made peace with Thomas, who was anxious to secure their support against the Marathas. Sahib Singh now proceeded to quarrel with his sister, and she died not long after- wards, having lost all influence in the State. Thomas then renewed his attacks on the Jind State, and as the Phulkian chiefs united to resist him he invaded Patiala territory and pillaged the town of Bhawanigarh. A peace was, however, patched up in 1801, and Thomas retired to Hansi, whereupon the Cis-Sutlej chiefs sent an embassy to General Perron at Delhi to ask for assistance, and Thomas was eventually crushed. The British now appeared on the scene ; but the Phulkian chiefs, who had been rescued from Thomas by the Marathas, were not disposed to join them, and reMained neutral throughout the operations round Delhi in 1803-4. Though Holkar was hospitably received at Patiala after his defeat at Dig, he could not obtain much active assistance from Sahib Singh. After Holkar's flight to Amritsar in 1805, the dissensions between Sahib Singh and his wife reached a climax, and the Rani attacked both Nabha and Jind. These States then invoked the intervention of Ranjit Singh, Maharaja of Lahore, who crossed the Sutlej in 1806. Ranjit Singh did little to settle the domestic differences of the Patiala Raja, but despoiled the widows of the Raikot chief of many villages. Patiala, however, received no share of the plunder ; and on Ranjit Singh's withdrawal the conflict between Sahib Singh and his wife was renewed. In 1807 Ranjit Singh reappeared at Patiala, when he conferred Banur and other districts, worth Rs. 50,000 a year, on the Rani and then marehed on Naraingarh.

It was by this time clear to the Cis-Sutlej chiefs that they had to choose between absorption by Ranjit Singh and the protection of the British. Accordingly, in 1808, Patiala, Jind, and Kaithal made overtures to the Resident at Delhi. No definite promise of protection was given at the time; but in April, 1809, the treaty with Ranjit Singh secured the Cis-Sutlej territory from further aggression on his part, and a week later the desired proclamation of protection was issued, which continued to ' the chiefs of Malwa and Sirhind . . . the exercise of the same rights and authority within their own posses- sions which they enjoyed before.' Two years later it became necessary to issue another proclamation of protection, this time to protect the Cis-Sutlej chiefs against one another. Meanwhile internal v!onfusion led to the armed interposition of the British Agent, who established the MaharSni As Kaur as regent with sole authority. She showed adininistrative ability and an unbending tenjper until the death of Maharaja Sahib Singh in 1813. He was succeeded by Maharaja Karm Singh, who was largely influenced at first by his mother and her minister Naunidhrai, generally known as Missar Naudha.

The Gurkha War broke out in 1814, and the Patiala contingent served under Colonel Ochterlony. In reward for their services, the British Government made a grant of sixteen parganas in the Simla Hills to Patiala, on payment of a nazarana of Rs. 2,80,000. Karm Singh's government was hampered by quarrels, first with his mother and later with his younger brother, Ajlt Singh, until the Hariana boundary dispute demanded all his attention. The English had overthrown the Marathas in 1803 and had completed the subjugation of the Bhattis in Bhattiana in 1818; but little attention was paid to the adininistration of the country, and Patiala began to encroach upon it, growing bolder each year, until in 1835 her colonists were firmly established. When the attention of the British Government was at last drawn to the matter, and a report called for, the Maharaja refused to adinit the British clalms, declined arbitration, and pro- tested loudly when a strip of country more than a hundred miles long and ten to twenty broad was transferred from his possessions to those of the British Government. The Government, however, listened to his protest, the question was reopened, and was not finally settled till 1856, when some 41 villages were handed over to Patiala. When hostilities between the British and the government of Lahore became certain at the close of 1845, Maharaja Karm Singh of Patiala declared his loyalty to the British ; but he died on December 23, the day after the battle of Ferozeshah, and was succeeded by his son Narindar Singh, then twenty-three years old. It would be idle to pretend that the same active spirit of loyalty obtained among the Cis-Sutlej chiefs in 1845 as showed itself in 1857. The Maharaja of Patiala knew that his interests were bound up with the success of the British, but his symPATTIies were with the Khalsa. However, he provided the British with supplies and carriage, besides a contin- gent of men. At the close of the war, he was rewarded with certain estates resumed from the Raja of Nabha. The Maharaja rawctioned the abolition of customs duties on the occasion of Lord Hardinge's visit in 1847.

The conduct of the Maharaja on the outbreak of the Mutiny is beyond praise. He was the acknowledged head of the Sikhs, and his hesitation or disloyalty would have been attended with the most disastrous results, while his ability, character, and high position would have mide him a formidable leader against the British. On hearing of the outbreaj:, he marehed that evening with all his available troops in the direction of Ambala. In his own territories he furnished supplies and carriage, #nd kept the roads clear. He gave a loan of 5 lakhs to Government and expressed his willingness to double the amount. His troops served with loyalty and distinction on many

occasions throughout the campaign. Of the value of the Maharaja's adhesion the Commissioner wrote : ' His support at such a crisis was worth a brigade of English troops to us, and served more to tran- quillize the people than a hundred official disclalmers could have done; After the Mutiny "the Narnaul division of the Jhajjar terri- tory, jurisdiction over Bhadaur, and the house in Delhi belonging to Begam Zlnat Mahal fell to the share of Patiala. The Maharaja's honorary titles were increased at the same time. The revenue of Narnaul, which had been estimated at 2 lakhs, was found to be only Rs. 1,70,000. On this, the Maharaja appealed for more territory. The British Government had given no guarantee, but was willing to reward the loyal service of Patiala still further; and consequently parts of Kanaud and Buddhuana, in Jhajjar, were conferred on the Maharaja. These new estates had an income of about one lakh, and the Maharaja gave a nazarana equal to twenty years' revenue.

In 1858 the Phulkian chiefs had united in asking for concessions from the British Government, of which the chief was the right of adoption. This was, after some delay, granted, with the happiest results. The power to inflict capital puriishment had been with- drawn in 1847, but was exercised during the Mutiny. This power was now formally restored. The Khamanon villages (the history of which is given under 'Adininistration' on p. 47) were transferred to Patiala in 1860. Maharaja Narindar Singh died in 1862 at the age of thirty-nine. He was a wise ruler and brave soldier. He was one of the first Indian chiefs to receive the K.C.S.I., and was also a member of the Indian Legislative Council during Lord Canning's viceroyalty.

His only son, Mohindar Singh, was a boy of ten at his father's death. A Council of Regency was appointed, which carried on the adininistration for eight years. The Maharaja only lived for six years after assuming power. During his reign the Sirhind Canal was rawc- tioned, though it was not opened until 1882. Patiala contributed one crore and 23 lakhs to the cost of construction. The Maharaja was liberal in measures connected with the improvement and general well-being of the country. He gave Rs. 70,000 to the University College, Lahore, and in 1873 he placed 10 lakhs at the disposal of Government for the relief of the famine-stricken people of Bengal. In 1875 ne was honoured by a visit from Lord Northbrook, who was then Viceroy, when the Mohindar College was founded* for the promotion of higher education in the State. Mohincjar Singh died suddenly in 1876. He had received the G.C.S.I. in 1871.

A long minority followed, for Maharaja Rajindar Singh was only four when his father died. During his minority, which ceased in 1890, the adininistration was carried on by a Council of Regency, composed of three officials under the presidency of Sardar Sir Dewa Singh, K.C.S.I. The finances of the State were carefully watched, and considerable savings effected, from which have been met the charges in connexion with the Sirhind Canal and the broad-gauge line of railway between Rajpura, Patiala, and Bhatinda, In 1879 the Patiala State sent a contingent of 1,100 men to the Afghan War. The Maharaja was exempted from the presentation of nazars in Darbar, in recognition of the services rendered by his troops on this occasion. He was the first chief to organize a corps of Imperial Service troops, and served with one regiment of these in the Tirah expedition of 1897. Maharaja Rajindar Singh died in 1900, and a third Council of Regency was formed. The present Maharaja, Bhupindar Singh, was born in 1891. He is now being educated at thfe Aitchison College, Lahore. He ranks first amongst the chiefs of the Punjab, and is entitled to a salute of 17 guns.

In 1900 it was decided by the Government of India to appoint a Political Agent for Patiala, and the other two Phulkian States of Jind and Nabha were included in the Agency, to which was after- wards added the Muhammadan State of Bahawalpur. The head- quarters of the Agency are at Patiala.

The Siva temples at KALALT, in the Narwana tahsil, contain some old carvings supposed to date from the eleventh century. Of PINJAUR, it has been remarked that no place south of the Jhelum has more traces of antiquity. The date of the sculptured temples of Bhima Devi and Baijnath has not been determined. The walls of the houses, &c., in the village are full of fragments of sculptures. The gardens, which are attributed to Fidai Khan, the foster-brother of Aurangzeb, were modelled on the Shalamar gardens at Lahore, and are surrounded by a wall originally made of the debris of ancient buildings, but the fragments of sculpture built into it are much damaged. At SUNAM are the reMains of one of the oldest mosques in India. At SIRHIND Malik Bahlol LodI assumed the title of Sultan in 1451, and his daughter was buried here in 1497, in a tomb still existing. The oldest buildings in the place are two fine double- domed tombs, traditionally known as those of the Master and the Disciple. The date is uncertain, but the style indicates the four- teenth century. Shah Zaman, the refugee monareh of Kabul, was buried in an old graveyard of great rawctity near the town. The first certain mention of Sirhind is in connexion with events which occurred in 1360, but the place has been confused by historians with Bhatinda or Tabarhind, a much older place. The fort at Sirhind was originally named Firozpur, probably after Firoz Shah. The tomb of Ibrahim Shah at NARNAUL, erected by his grandson, the emperor Sher Shah (1540-5), with its massive proportions, deeply recessed doorways, and exquisite carvings, is a fine example of the Pathan style. Bhatinda was a place of great importance in the pre-Mughal days; but the date of the fort, which is a conspicuous feature in the landscape for miles round, is unknown. At Patiala and at Bahadur- garh, near Patiala, are fine forts built by chiefs of Patiala.

Population

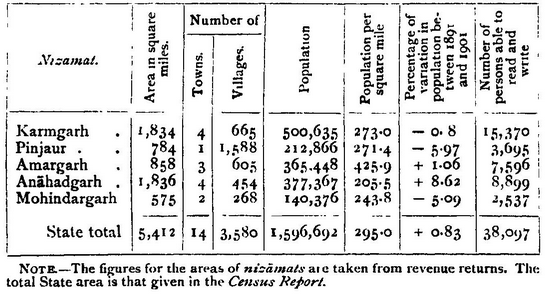

The State contains 14 towns and 3,580 villages. Its population at the last three enumerations was: (1881) 1,467,433, (1891) 1,583,521, and (1901) 1,596,692. The small increase in the last decade was due to the famines of 1897 and 1900, which caused much emigration from the Mohindargarh nizamat. The State is divided into the five nizamats, or adininistrative districts, of KARMGARH, PINJAUR, AMARGARH, ANAHADGARH, and MOHINDARGARH. The head-quarters of these are at Bhawanigarh, Basi, Barnala, Rajpura, and Kanaud respectively. The towns are PATIALA, the capital, NAR- NAUL, BASI, Govindgarh or BHATINDA, SAMANA, SUNAM, Mohindargarh or KANAUD, RAWAUR, BHADAUR, BARNALA, BANUR, PAIL, SIRHIND, and HADIAYA.

The following table shows the chief statistics of population in 1901 :

Hindus form 55 per cent, of the total, and Sikhs, though Patiala is the leading Sikh State of the Punjab, only 22 per cent., slightly less than Muhammadans. Jains, fewer than 3,000 in number, are mostly found in the Mohindargarh nizamat. The density, though higher than the Provincial average for British Districts, is lower than the average of the Districts and States situated in the Indo-Gangetic Plaln West. It is lowest in the Anahadgarh nizamat, where less than 14 per cent, of the total area is cultivated. There is not, however, much room for extension of cultivation, as the cultivable tracts are fully populated. Punjabi is the language of 88 per cent, of the population.

Nearly every caste in the Punjab is represented in Patiala, but the Jats or Jats, who comprise 30 per cent, of the population, are by far its strongest element. Other cultivating castes are the Rajputs, Ahirs (in Mohindargarh), Gujars, Arains, and Kambohs. Brahmans and Fakirs number nearly 8 per cent, of the population ; and artiraw and menial castes, such as the Chamars, Chuhras, Tarkhans, &c., comprise most of the residue. Of the whole population, 62 per cent, are dependent on agriculture ; and the State has no important industries, other than those carried on in villages to meet the ordinary wants of an agricultural population.

In 1901 the State contained 122 native Christians. The principal missionary agency is that of the American Reformed Presbyterian Church, which was established in 1892, when Maharaja Rajindar Singh permitted Dr. Scott, a medical missionary of that Church, to establish a mission at Patiala town, granting him a valuable site for its buildings. The only other society working among the native Christians is the American Methodist Episcopal Mission, established at Patiala in 1890. In the village of Rampur Katani (Pail tahsil) an Anglo- vernacular primary school, started by the Ludhiana American Mission, teaches 22 Jat and Muhammadan boys. There is also a small mission school at Basi, where twelve or thirteen sweeper boys are taught.

Agriculture

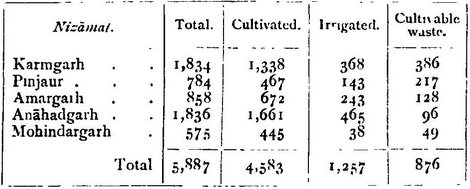

Agricultural conditions are as diversified as the territory is scattered. In the Pinjaur tahsil they resemble those of the surrounding Simla Hill States, and in the Mohindargarh nizamat those of Rajputana. Elsewhere the State consists of level plalns with varying characteristics. The Rajpura, Banur, and Ghanaur tahsils of the Pinjaur nizamat, the Patiala and part of the Bhawanigarh tahsil of the Karmgarh nizamat, and the Fatehgarh (Sirhind) and Sahibgarh (Pail) tahsils of the Amargarh nizamat lie in the Pawadh, a naturally fertile tract of rich loam. Sirhind and Pail are both pro- tected by wells, and, though not irrigated by canals, are the richest in the State from an agricultural point of view. The Narwana tahsil lies in the Bangar, a plateau or upland in which the spring-level is too low for wells to be profitably sunk. The reMaining parts of these three nizamats, and the whole of Anahadgarh, lie in the Jangal, a tract naturally fertile, but unproductive owing to the absence of rain and the depth of the spring-level until irrigated by the Sirhind Canal. The Jangal consists of a great plaln of soft loam covered with shifting rawdhills, with a few wells on the borders of the Pawadh ; but agri- culturally it is in a transition stage, as the canal permits of intensive cultivation. The bhaiyachara is the general form of tenure, except in Mohindar- garh, where the pattidari form is prevalent. The Main agricultural statistics for 1903-4 are given in the table on the next page.

The principal food-grains cultivated are gram (area in 1903-4, 660 square miles), barley and gram mixed (587), wheat (432), bajra (367), jowar (362), wheat and gram mixed (284), and maize (239). Mustard covered 286 square miles, chari (jowar grown for fodder) 238, and cotton 72. In the hill tract (Pinjaur tahsil) potatoes, ginger, turmeric, and rice are the most valuable crops, and Indian corn is largely grown for food. In the Sirhind and Pail tahsil sugar-cane is the most paying crop. It is also grown in parts of the Patiala, Amargarh, and Bhawanigarh tahsil. Cotton is grown generally in all but the rawdy tracts of the south-west, and it forms the staple crop in Narwana. Tobacco is an important crop in the Pawadh tract. Rice is grown in the three tahsil of the Pinjaur nizamatwhich lie in the Pawadh. Wheat is the staple crop in the north-wesstern half, barley and gram, separately or mixed, in the south and west, and millet in the Mohindargarh nizamat. In the latter millet is an autumn crop, dependent on the monsoon rains. In the rest of the State the spring harvest is more important than the autumn harvest, and its importance increases as canal-irrigation is developed.

Cash rents are very rare. The landlord's share of the produce varies from one-fifth to one-half, and one-third may be taken as the average rate. Land irrigated from wells usually pays a higher rate than other land, except in the dry tracts to the west and south, where the soil is inferior and the expense of working wells heavy. The highest rates are paid in the submontane country to the north and east of Patiala. The wages of unskilled labour when paid in cash, as is generally the case in towns and more rarely in the villages, vary from 3 annas a day in outlying tracts to 6 annas in the capital. A reaper earns from 6 to 1 2 annas a day, and a carpenter from 8 to 1 2 annas or even R. 1 in the hills. Prices have risen about 12 per cent, in the last fifteen years.

Few State loans to cultivators were made prior to the revision of the settlement which began in 1901 and is still proceeding, and Very high rates of interest were charged. During the three years ending 1906, a total of nearly Rs. 80,000 was advanced. The rate of interest on loans for the construction of wells and the purchase of bullocks is just under 4 3/4 per cent., while loans for the purchase of seed are given free of interest.

The cattle of the Jangal in the south-west and of Mohindargarh are fine up-standing animals, but the cows are poor milkers, and cattle- breeding hardly exists. Ponies of a fair class are raised in the Bangar, in the Narwana tahsil; and there is a State stud at Patiala, established in 1890, with 5 horse, 1 pony, and 3 donkey stallions, and 25 brood-mares.

Fairs are held twice a year at Karauta and Dharson, both in the Mohindargarh nizamat, at which about 20,000 cattle change hands yearly. Cattle fairs were also started in 19034 at Bhatinda, Barnala, Mansa, Boha, Dhamtansahib, Sunam, Patiala, Rajpura, Dhuri, Sirhind, and Kanaud.

Of the total area under cultivation in 1903-4, 1,257 square miles, or 27 per cent, were classed as irrigated. Of this area, 342 square miles, or 27 per cent., were irrigated from wells, and the rest from canals. The State contains 12,696 wells in use, besides unbricked wells, lever wells, and water-lifts. Patiala owns 84 per cent, of the share (36 per cent.) of the Sirhind Canal possessed by the Phulkian States. The Hissar branch of the Wesstern Jumna Canal, which irrigated 85 square miles in 1903-4, also secures against famine a large pait of the Narwana tahsil '; and in the tahslh of Baniir and Ghanaur a small inundation canal from the Ghaggar, which irrigated 14 square miles in 1903-4, serves a number of villages. Wells are Mainly confined to the Pawadh and the part of the Jangal which adjoins it. Wells are also used in the Mohindargarh nizamat, but the water in some is brackish and only beneficial after rain. Jats generally use the bucket and Arains the Persian wheel on a masonry well, but some of the Arains and Kambohs in the Baniir tahsil use the dingli or lift.

Forests

In the hill thanas of Pinjaur, Dharmpur, and Srlnagar, in the Pinjaur Dun and Siwaliks, the State possesses valuable forests, in which con- siderable quantities of chll (Pin us longifolLi), pine, oak, deodar, and bamboo are found. The first and second-class forests have an area of 109 square miles, with 171 square miles of grass lands. It also possesses several * reserves ' (birs) aggre- gating 12,000 acres in the plalns. The forests are controlled by a Conservator, who has two assistants in the hills and one in the plalns. Avenues of shisham (Dalbergia Sissoo) are planted along the canal banks, and of klkar (Acacia arabica) along the roads. The forest revenue in 1903-4 was Rs. 51,000.

Kankar is found at many places. Slate, limestone, and rawdstone occur in the Pinjaur hills, and in the detached hills of the Mohindar- garh nizamat. Saltperre is manufactured in the Rajpura, Ghanaur, Banur, Narwana, and Narnaul tahsils, and carbonate of soda in the Bangar. Copper and lead ores are found near Solon ; and mica and copper and iron ores in the Mohindargarh nizamat.

Trade and communications

Manufactures, other than the ordinary village industries, are virtually confined to the towns. Cotton fabrics are made at Sunam, and silk at Patiala. Gold lace is manufactured at Patiala, and silsi at Patiala and Basi, the latter being of fine quality. At Samana communications. and Narnaul le g s for beds are turned, and at Pail carved doorways are made. Ironware is also pro- duced at four villages. Brass and bell-metal are worked at Patiala and Bhadaur, and at Kanaud (Mohindargarh), where ironware is also manufactured. The only steam cotton-ginning factory in the State is at Narwana. A workshop is situated at Patiala. The number of factory hands in 1903-4 was 80.

The State exports grain in large quantities, principally wheat, gram, rapesecd, millet, and pulses, with ghi, raw cotton and yarn, red pepper, saltperre, and lime. It imports raw and refined sugar and rice from the United Provinces, piece-goods from Delhi and Bombay, and various other manufactures. The principal grain marts are at Patiala, Narnaul, Basi, Barnala, Bhatinda, and Narwana; but grain is also exported to the adjoining British Districts and to Nabha.

The North- Wesstern Railway traverses the north of the State through Rajpura and Sirhind, and the Rajpura-Bhatinda branch passes through its centre, with stations at the capital, DhQri Junction, Barnala, and Bhatinda. The latter line is owned by the State, but worked by the North-Wesstern Railway. The Ludhiana-Dhuri-Jakhal Railway, with stations at Dhuri and Sunam, also serves this part of the State. The Southern Punjab Railway passes along the southern border, with a station at Narwana in the Karmgarh nizamat. A mono-rail tramway, opened in February, 1907, connects Basi with the railway at Sirhind. There are 185 miles of metalled roads, all in the plalns, and about 194 miles (113 in the plalns and 81 in the hills) of unmetalled roads in the State. Of the former, the principal connects Patiala with Sunam (43 miles), one branch leading to Rawgrfir, the capital of Jfnd State, and another to Samana. The others are Mainly feeder roads to the railways. There are avenues of trees along 142 miles of road.

The postal arrangements of the State are governed by the convention of 1884, as modified in 1900, which established a mutual exchange of all postal articles between the British Post Office and the State post. The ordinary British stamps, surcharged ‘ Patiala State’ are used. Under an agreement concluded in 1872, a telegraph line from Ambala to Patiala was constructed by Government at the expense of the State, which takes all the receipts and pays for the Maintenance of the line.

Famine

The earliest and most terrible of the still-remembered famines was the chdltsa of Samvat 1840 (A.D. 1783), which depopulated huge tracts in the Southern Punjab. , In 1812 and 1833 the State again suffered. The famine of 1860-1 was the first in which relief was systematically organized by the State. Relief works were opened; over 11,000 tons of grain were distributed, and 3 3/4 lakhs of revenue was remitted. The famine of 1897 cost the State nearly 2 lakhs in relief works alone. Three years later came the great famine of 1900. It was a fodder famine as well as a grain famine, and cattle died in large numbers. Relief measures were organized on the lines lald down for the British Districts of the Province. Nearly 4 lakhs was spent on relief works and gratuitous relief. Two lakhs of revenue was remitted and 2 1/2 lakhs was suspended.

Administration

The Political Agent for the Phulkian States and Bahawalpur resides at Patiala. He is the representative of the Licutenant-Governor, and is the channel of communication in most matters between the State authorities on the one hand and British officials or other States on the other. He has no control over the State courts, but he hears appeals from the orders of certain of the District Magistrates, &c., of British Districts, in their capacity as Railway Magistrates for the various railways which pass through Patiala territory.

During the minority of the Maharaja, his functions are exercised by a Council of Regency consisting of three members. There are four departments of State : the finance department (Diwan-i-Mal) under the Diwan, who deals with all matters of revenue and finance, the foreign department (Munshi Khdna) under the Mir Munshi, the judicial department (Sadr Addlaf) under the Adalati, and the military department (Bakhshi Khdna) under the Bakhshi or commander-in- chief. The Chief Court was created by Maharaja Rajindar Singh, to hear appeals from the orders of the finance, foreign, and judicial ministers. There is no regular legislative department. Regulations are drafted in the department concerned and submitted for rawction to the Ijlas-i-Khas, or court of the Maharaja. Under the present arrangements the power of rawction rests with the Council of Regency, the members of which possess the power of initiation. For general adininistrative purposes the State is divided into five nizamats, each being under a nazim, who exercises executive powers and has sub- ordinate to him two or three naib (deputy) nazims in each nizamat, and a tahsildar in each tahsil

The lowest court of original jurisdiction in civil and revenue cases is that of the tahsildar , from whose decisions appeals lie to the nazim. The next higher court is that of the naib-nazim, who exercises criminal and civifr powers, and from whose decisions appeals also lie to the nazim. The nazim is a Sessions Judge, with power to pass sentences of imprisonment not exceeding fourteen years, as well as an appellate court in criminal, civil, and revenue cases. From his decisions appeals lie in criminal and civil cases to the Sadr Adalat and in revenue cases to the Diwan, with a second appeal to the Chief Court, and a third to the Ijlas-i-Khas ; both the last-mentioned courts also exercise revisional jurisdiction in all cases. All sentences of death or transportation for life require the confirmation of the Maharaja, or, during his minority, of the Council of Regency.

Special jurisdiction in criminal cases is also exercised by the following officials. The Mir Munshi, or foreign minister, has the powers of a Sessions Judge with respect to cases in which one or both parties are not subjects of the State ; cases under the Telegraph and Railway Acts are decided by a special magistrate, from whose decision an appeal lies to the Mir Munshi; certain canal and forest officers exercise magisterial powers in respect of offences concerning those departments; and the Inspector-General exercises similar powers in respect of cases in which the police are concerned. During the settle- ment operations the settlement officers are also invested with power to decide revenue cases, and from their decisions appeals lie to the Settlement Commissioner. At the capital there are a magistrate and a civil judge, from whose decisions appeals lie to the Mudwtn Adalat.

The Sikh Jats are addicted to crimes of violence, illicit distillation, and traffic in women, the Hindu Jats and the Rajputs to cattle-theft, and the Chuhras to theft and house-breaking, while the criminal tribes Rawsls, Baurias, Baloch, and Minis are notorious for theft, robbery, and burglary.

In 1902 a few panchdyats were established in the Narwana and Govindgarh tahsil for the settlement of disputes of a civil nature. The experiment has proved successful, and there are now 76 of these rural courts scattered about the State. Up to the end of 1906, they had disposed of more than 45,000 cases, the value of the clalms dealt with being considerably over 60 lakhs. The parties have the right to challenge the decision of the panchdyat in the ordinary courts, but up to the present less than 2 per cent, of the decisions in disputed cases have been challenged in this manner.

The chief of the feudatories are the Sardars of Bhadaur, who between them enjoy a jagir of over Rs. 70,000 per annum. Like the ruling family, they are descendants of Phul ; but in 1855 the clalm of Patiala to regard the Bhadaur chiefs as feudatories of her own was disallowed by Government, and their villages were brought under British jurisdiction. Three years later the supremacy over Bhadaur was ceded to the Maharaja as a small portion of the reward for his loyalty in 1857. The tenure of the jagir is subject to much f the same incidents in respect of lapse and commutation as similar assignments in the British portion of the Cis-Sutlej territory. There are at present six sharers in the jagir, while the widows of deceased members of the family 'whose shares have lapsed to the State receive Maintenance allowances amounting to Rs. 8,699.

The numerous jaglrdars of the Khamanon villages receive between them over Rs. 90,000 a year from the State, and are entitled, in addition, to various dues from the villagers. Ever since 1815 Patiala had been held responsible for the general adininistration of this estate, though the British Government reserved its rights to escheats and military service. In 1847 the question of bringing the villages entirely under British jurisdiction was mooted. The negotiations were prolonged until after the Mutiny, when, in 1860, Government trans- ferred its rights in the estate to Patiala in return for a nazarana of Rs. 1,76,360. The jagirdars are exempted from the appellate juris- diction of the ordinary courts, and are entitled to have their appeals heard by the foreign minister. The jaglrdars of Pail constitute the only reMaining group of assignees of any importance. Their jagirs amount in all to over Rs. 18,000, and are subject to the usual incidents of lapse and commutation.

The Main area of the State corresponds roughly to the old Mughal sarkdr of Sirhind, and was subject to Akbar's fiscal reforms. Formerly the State used to collect nearly all its revenue in kind, taking generally one-third of the produce as its share, calculated either by actual division or by a rough and ready appraisement. In 1862 a cash assessment was first made. It resulted in a total demand of about 30-9 lakhs, reduced three years later to 29.4 lakhs. Afterwards summary assessments were made every ten years, until in 1901 a regular settlement was undertaken, a British officer being appointed Settlement Commissioner. The present demand is 41.5 lakhs or, including cesses and other dues, 44.8 lakhs, of which 4.7 lakhs are assigned, leaving a balance of 40 lakhs realizable by the State. The revenue rates on unirrigated land vary from a minimum of R. 0-6-4 in parts of Mohindargarh to a maximum of Rs. 5-11-3 in the Bet circle of the Sirhind tahsil, and on irrigated land from 12 annas in Pail to Rs. 9-9-6 in the Dhaya circle of Sirhind. There are wide variations from circle to circle in the average rates. The average 'dry' rate in one of the Mohindargarh circles is ten annas, while in the Bet of Sirhind it is Rs. 3-14-6. Similarly, the average 'wet 1 rate in the Sunam tahsil is Rs. 1-13-4, and in the Dhaya of Sirhind Rs. 5-11-3- The collections of land revenue alone and of total revenue are shown bejow, in thourawds of rupees :

The principal sources of revenue, other than land revenue, and the amounts derived from each in 1903-4, are: public works, including irrigation and railways (14-1 lakhs), excise (2.2 lakhs), octroi (1.9 lakhs), stamps (1.7 lakhs), and provincial rates (1.4 lakhs); while the Main heads of expenditure are public works (14.4 lakhs), army (9-1 lakhs), civil list (4.5 lakhs), police (4.2 lakhs), land revenue adininistration (4 lakhs), general adininistration (3 lakhs), religious and charitable endowments (1-9 lakhs), and medical (1.8 lakhs).

The right of coinage was conferred on Raja Amar Singh by Ahmad Shah Durrani in 1767. No copper coin was ever minted, and only on one occasion, in the reign of Maharaja Narindar Singh, were 8-anna and 4-anna pieces struck ; but rupees and gold coins or ashrafis were coined at intervals up to 1895, when the mint was closed for ordinary coinage. Up to the last the coins bore the legend that they were struck under the authority of Ahmad Shah, and the coinage of each chief bore a distinguishing device, generally a representation of some kind of weapon. The Patiala rupee was known as the Raja shahi rupee. It was rather lighter than the British rupee, but contained the same amount of silver. Rupees known as Ndnak shahi rupees, which are used in connexion with religious ceremonies at the Dasahra and Dlwali festivals, are still coined, with the inscription Degh, tegh o fateh nusrat be darang. Yaft as Nanak Guru Gobind Singh.

Prior to 1874, the distillation, the sale, and even the use of liquor were prohibited. The present arrangement is that no distillation is allowed except at the central distillery at Patiala town. The distiller there pays a still-head duty of Rs. 4 per gallon. The licences for retail sale are auctioned, except in the case of European liquor, the vendors of which pay Rs. 200 or Rs. 100 per annum according as their sales do or do not exceed 2,000 bottles. The State is privileged to receive a number of chests of Malwa opium every year at a reduced duty of Rs. 280 per chest of 140^ Ib. The number is fixed annually by the Government of the Punjab, and varies from 74 to 80. For anything over and above this amount, the full duty of Rs. 725 per chest is paid. The duty paid on the Malwa opium imported has, since 1891, been refunded to the State, with the object of securing the hearty co- operation of the State officials in the suppression of smuggling. Import of opium into British territory from the Mohindargarh nizamat is prohibited. The importers of opium into Patiala pay p. duty of R. i per seer to the State. Licences for the retail sale of opium and hemp drugs are sold by auction. Wholesale licences' for the sale of liquor, opium, and drugs are issued on payment of small fixed fees. Patiala town was constituted a municipality in 1904 and Narnaul in 1906.

The Public Works department was reorganized in 1903 under a Superintending Engineer, who is subject to the control of one of the members of Council of the Regency. An extensive programme of public works has been framed, the total cost of which will be 85 lakhs ; and a considerable portion of it has been carried out at a cost of 25 lakhs during the three years that have elapsed since the reorganiza- tion of the department. Public offices, tahsils police stations, schools, dispensaries, markets, and barracks have been erected. The darbdr chamber in Patiala Fort has been remodelled and reroofed, and is now a magnificent hall. A large Central jail has been constructed at Patiala, and a number of new roads have been made. Among build- ings erected during the last few years by private subscription may be mentioned the Victoria Memorial Poorhouse at Patiala, which cost Rs. 80,000, and the Victoria Girls' School, which cost half that sum.

In 1903-4 the regular police force consisted of 1,973 of all ranks. The village watchmen numbered 2,775. There are 42 police stations, 3 outposts, and 17 road-posts. The force is under the control of an Inspector-General. District Superintendents are appointed for each nizamatwith inspectors under them, while each police station is in charge of a thanadar. The State contains two jails, the Central jail at the capital and the other at Mohindargarh, which hold 1,100 and 50 prisoners respectively. The Imperial Service contingent Maintained by the State consists of a regiment of cavalry and two battalions of infantry. The local troops consist of a regiment of cavalry, two battalions of infantry, and a battery of artillery with eight guns. The State possesses altogether fifty serviceable guns. The total strength of the State army- officers, non-commissioned officers, and men is 3,429.

Patiala is the most backward of the larger States of the Punjab in point of education. The percentage of literate persons is only 2-4 (4-2 males and o-i females) as compared with 2-7, the average for the States of the Province. The percentage of literate females doubled between 1891 and 1901, but that of literate males declined from 5.3 to 4.2. The number of persons under instruction was 6,479 m 1880-1, 6,187 m 1890-1, 6,058 in 1900-1, and 6,090 in 1903-4. In the last year the State possessed an Arts college, 21 secondary and 89 primary (public) schools, and 3 advanced and 129 elementary (private) schools, with 538 girls in the public and 123 in the private schools. The expenditure on education was Rs. 83,303. The Director of Public Instruction is in charge of education, and under him are two inspectors.

The State possesses altogether 34 hospitals, and dispensaries, of which 10 contain accommodation for 165 in-patients. In 1903-4 the number of cases treated was 198,527, of whom 2,483 were in-patients, and 10,957 operations were performed. The expenditure was Rs. 87,076, wholly met from State funds. The adininistration is usually controlled by an officer of the Indian Medical Service, who is medical adviser to the Maharaja, with nine Assistant Surgeons. The Sadr and Lady Dufferin Hospitals at the capital are fine buildings, well equipped, and a training school for midwives and nurses was opened in 1906.

Vaccination is controlled by an inspector of vaccination and regis- tration of vital statistics, under whom are a supervisor and thirty vaccinators. In 1903-4 the number of persons successfully vaccinated was 43,782, or 27 per 1,000 of the population. Vaccination is no- where compulsory.

The Bhadaur villages in the Anahadgarh tahsil were surveyed and mapped by the revenue staff in 1854-5, and the whole of the Mohindargarh tahsil in 1858, while they were still British territory. In 1877-9 a revenue survey of the whole State, except the Pinjaur tahsil) was carried out; but maps were not made except for the Mohindargarh and Anahadgarh nisatnats, and for a few scattered villages elsewhere. During the present settlement, the whole of the State is being resurveyed, and the maps will be complete in 1907.

The first trigonometrical survey was made in 1847-9, an d maps were published on the i-inch and 2-inch scales; but the Pinjaur tahsil was not surveyed until 1886-92, when 2-inch maps were published. A 4-inch map of the Cis-Sutlej States was published in 1863, and in the revised edition of 1897 the Pinjaur tahsil was included. The i-inch maps prepared in 1847-9 were revised in 1886-92.

[H. A. Rose, Phulkian States Gazetteer (in the presb) ; L. H. Griffin, The Rajas of the Punjab (second edition, 1873); Khalifa Muhammad Haraw, Tarikh-i- Patiala (1877); also the various Histories of the Sikhs.]