Peshawar District, 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents[hide] |

Peshawar District

District in the North-West Frontier Province, and the most north-western of the regularly administered Districts in the Indian Empire. It lies between 33 43' and 34 32" N. and 71 22' and 72 45' E., with an area of 2,611 square miles. It is bounded on the east by the Indus, which separates it from the Punjab District of Attock and from Hazara. On all other sides it is encircled by mountains, at the foot of which, except on the south-east, the administrative border runs. These hills are inhabited by independent tribes, whose territories lie in the following order, beginning from the north-east corner, where the boundary leaves the river. The Utmanzai, Gadun, Khudu Khel, and Salarzai clans are hamsayas of the Bunerwals ; north of Mardan lies a small piece of Utman Khel country, west of which is Sam Ranizai sloping up to the Malakand pass ; beyond Sam Ranizai comes the main Utman Khel country, which stretches as far as Abazai on the Swat river ; the country between the Swat and Kabul rivers belongs to the Burhan Khel, Halimzai, and Tarakzai Mohmands ; from the Kabul river to Jamrud at the mouth of the Khyber Pass is Mullagori country ; the hills between the Khyber and the Kohat Pass are the abode of the Malikdin and Aka Khel Afrldis ; on both sides of the Kohat Pass live the tribes known as the Pass Afrldis, beyond whom on the south side of the District live the Jowakis, whose territory runs nearly as far as Cherat. East of Cherat the range is inhabited by Khattaks, and forms, except for the Khwarra and Zira forest on the banks of the Indus, part of Kohat District.

Physical aspects

To the north-east great spurs, separated by intricate lateral valleys, run into the District, the Mora, Shakot, and Malakand passes leading through them into Swat. From the north-west out- lying ranges of the Hindu Kush run down the aspects, western border, loftily isolated peaks to the north merging in the confused and precipitous heights on the south bank of the Kabul river. South of the Khyber, the range sinks to a mean level of 4,000 feet, and at the point where the Kohat pass leads out of the District turns sharp to the east, and runs along the south border of the District to the Indus. On this side the highest points are Cherat, with an elevation of nearly 4,500 feet, and the Ghaibana Sir, 5,136 feet above sea-level. The shape of the District is an almost perfect ellipse, the greatest length of which is 86 miles, its greatest width being 54 miles.

Viewed from a height it appears a vast plateau, whose vivid expanse of green is in abrupt contrast with the grey precipitous slopes of the hills which rise sharply from its edge ; but its true formation is that of a huge basin into which flow the waters from the surrounding hills. This basin is drained by the Kabul river, which traverses the valley eastwards from its debouchure through a deep ravine north of the Khyber Pass until it falls into the Indus above Attock. Throughout its course the Kabul is joined by countless tributaries, of which the principal is the Swat ; and before they unite below Prang (Charsadda), about 24 miles from the hills, these two rivers cover the central part of the western plain with a perfect network of streams, as each divides into several channels. The Bara, flowing from the south-west, also enters the Kabul near its junction with the Swat ; and the united stream, now known as the Landai, or 'short river; flows for 12 miles in a wide bed as far as Naushahra, and thence for 24 miles in a deep channel to the Indus. Other streams are the Budni, a branch of the Kabul; and the KalpanI or ChalpanI, the 'deceitful water; which, rising beyond the Mora pass, receives the drainage of the Yusufzai plain and falls into the Landai below Naushahra.

Peshawar has not been geologically surveyed, but the general struc- ture of the District appears to be a continuation westwards of that of Hazara. Judging from partial traverses and from information of various kinds, one may say that its northern portions, including the hills on the northern border, are composed, like Hazara, of meta- morphic schists and gneissose rocks. Much of the flat plain of Peshawar and Naushahra and the northern slopes of the Cherat hills consist of a great slate series with minor limestone and marble bands, some of which are worked for ornamental purposes. South of the axis of the Cherat range, the rest of the District is apparently composed of a medley of folded representatives of Jurassic, Cretaceous, and Nummulitic formations. They consist of limestones, shales, and sandstones of marine origin, the general strike of the rock bands being east and west across the Indus in the direction of Hazara and Rawalpindi. Much of the valley of Peshawar is covered with sur- face gravels and alluvium, the deposit of the streams joining the Kabul river on its way to the Indus

1 W. Waagen, 'Section along the Indus from the Peshawar Valley to the Salt Range; Records, Geological Survey of India , vol. xvii, pt. iii.

The District, wherever irrigated, abounds in trees, of which the mulberry, shisham, willow, tamarisk, and tallow-tree are the most common. In the drier parts scrub jungle grows freely, but trees are scarce, the palosi or ber being the most frequent. The more common plants are Flacourtia sapida, F. sepiaria, several species of Grewia, Zizyphus nummularia, Acacia Jacquemontii, A. hucophloea, Alhagi Camelorum, Crotalaria Burhia, Prosopis spirigera, several species of Tamariv, Nerium odorum, Rhazya stricta, Calotropis procera, Peri- ploca aphylla, Tecoma undulata, Lycium europaeum, Withania coagu- lans, W. somnifera, Nannorhops Ritchieana, Fagonia, Tributes, Peganum Harmala, Calligonum polygonoides, Polygonum aviculare, P. plebejum, Rumex vesicarius, Chrozophora plicata, species of Aristida, Anthi- stiria, Cenchrus, and Pennisetum.

The fauna is meagre. Markhor are found on the Pajja spurs which jut out from the hills north of Mardan, and occasionally near Cherat, where urial are also seen. Wolves and hyenas are now not numerous, but leopards are still met with, though rarely. The game-birds are those of the Northern Punjab; and though hawkirg and snaring are favourite amusements of the people and many possess firearms, wild- fowl of all the migratory aquatic species, including sometimes wild swans, abound in the winter. Non-migratory species are decreasing as cultivation extends. The Peshawar Vale Hunt maintains an excel- lent pack of hounds, the only one in Northern India, and affords capital sport to the large garrison of Peshawar. There is fishing in many of the streams near the hills.

The best time of the year is the spring, February to April being the months when the air, though cold, is bracing. December and January are the coldest months, when the temperature sometimes falls below 30 and the nights are intensely cold. During the hot season, from May to July, the air is full of dust-haze. Dust-storms are frequent, but, though thunderstorms occur on the surrounding hills, rain seldom falls in the plains. This season is, however, healthy, in contrast to the next months, August to October, when the hot-season rains fall and the air is stagnant and oppressive. After a fall of rain the atmosphere becomes steamy and fever is common. In November the days are hot owing to the clear atmosphere, but the nights are cold. Showers are usual during winter. Inflammatory diseases of the lungs and bowels and malarial fever are prevalent at this season. The principal disease fr5m which the valley, and especially the western half of it, suffers is malarial fever, which in years of heavy rainfall assumes a very deadly form, death often supervening in a few hours.

The annual rainfall varies from 11 inches at Charsadda to 17 1/2 at Mardan. Of the total at Mardan, n inches fall in the summer and 6 1/2 in the winter. The heaviest rainfall during the last twenty years was 35 inches at Mardan in 1882-3, and the lightest 3 inches at Katlang in 1883-4.

History

The ancient Hindu name for the valley of Peshawar as it appears in Sanskrit literature is GANDHARA, corresponding to the Gandarites of Strabo and the country of the Gandarae described by ptolemy, though Arrian speaks of the people who held the valley against Alexander as Assakenoi. Its capital, Peu- kelaotis (or Pushkalavati), is mentioned by Arrian as a large and populous city, captured by Hephaistion, the general of Alexander, after the death of its chieftain Astes. The site of Pushkalavati has been identified with Charsadda, where extensive mounds of ancient debris are still to be seen. The Peshawar and Kabul valleys were ceded by Seleucus to Chandragupta in 303 B.C., and the rock edicts of Asoka at Mansehra and Shahbazgarhi show that Buddhism had become the state religion fifty years later. The Peshawar valley was annexed by the Graeco-Bactrian king Eucratides in the second cen- tury, and about the beginning of the Christian era fell under the rule of the Kushans. It is to the intercourse between the Greeks and the Buddhists of this part of India that we owe the school of art known as Graeco-Buddhist, which in turn served as the source of much that is fundamental in the ecclesiastical art of Tibet, China, and Farther Asia generally. For it was in this District that the Mahayana school of Buddhism arose, and from it that it spread over the Asiatic continent. Buddhism was still the dominant religion when Fa Hian passed through in the fifth century A.D. Sung Yun, who visited Peshawar in 520, mentions that the Ephthalite king of Gandhara was at war with the king of Kabul ; but at the time of Hiuen Tsiang's visit in 630 Gandhara was a dependency of Kabul. Buddhism was "then falling into decay.

Until the middle of the seventh century, epigraphic evidence shows that the population remained entirely Indian, and Hinduized rulers of Indo-Scythian and Turkish descent retained possession of Peshawar itself and of the Hashtnagar and Yusufzai plains. They were suc- ceeded by the so-called Hindu Shahis of Kabul or Ohind. In 979 one of these, Jaipal, advanced from Peshawar to attack Sabuktagln, governor of Khorasan under the titular sway of the Samani princes ; but peace was effected and he retired. Nine years later Jaipal was utterly defeated at Laghman, and Sabuktagln took possession of Peshawar, which he garrisoned with 10,000 horse.

On his death in 998, his son Mahamad succeeded to his dominions, and, throwing off his nominal allegiance to the Samani dynasty, assumed the title of Sultan in 999. In 1006 Mahmud again invaded the Punjab; and on his return Jaipals son and successor, Anandpal, attempted to intercept him, but was defeated near Peshawar and driven into Kashmir. But he was able to organize further resistance, for in 1009 he again encountered Mahmud, probably at Bhatinda, on the Indus, where he met with his final overthrow. The Ghaznivid monarchy in turn fell before Muhammad of Ghor in 1181 ; and after his death in 1206 the provincial governors declared their indepen- dence, making the Indus their western boundary, so that the Pesh- awar valley was again cut off from the eastern kingdom. In 1221 the Mongols under Chingiz Khan established a loose supremacy over it. About the close of the fifteenth century, a great tide of Afghan immi- gration flowed into the District. Before Tlmur's invasion the Dilazaks had been settled in the Peshawar valley, in alliance with the Shalmanis, a Tajik race, subjects of the rulers of Swat. The Khakhai (Khashi) Afghans, a body of roving adventurers, who first come into notice in the time of Timur, were treacherously expelled from Kabul by his descendant Ulugh Beg, whereupon they entered the Peshawar valley in three main clans the Yusufzai, Gigianis, and Muhammadzai and obtained permission from the Dilazaks to settle on a portion of their waste lands. But the new immigrants soon picked a quarrel with their hosts, whom they attacked.

In 1519 Babar, with the aid of the Dilazaks, inflicted severe punish- ment on the Yusufzai clans to the north of the District; but before his death (1530) they had regained their independence, and the Dilazaks even dared to burn his fort at Peshawar. The fort was rebuilt in 1553 by Babar's successor, Humayun, after defeating his brother Mirza Kamran, who had been supported against Humayun by the Ghorai Khel tribes (Khallls, Daudzai, and Mohmands), now first heard of in connexion with Peshawar. After his victory Humayun returned to Hindustan. On his departure the Ghorai Khel entered into alliance with the Khakhai Khel, and their united forces routed the Dilazaks and drove them out of the District across the Indus. The Ghorai Khel and Khakhai Khel then divided the valley and settled in the portions of it still occupied by them, no later tribal immigration occurring to dispossess them.

The Khalils and a branch of the Mohmands took the south-west corner of the District ; to the north of them settled the Daudzai ; the remaining Mohmands for the most part stayed in the hills, but settlers gradually took possession of the triangle of land between the hills and the Swat and Kabul rivers ; the east portion of the District fell to the Khakhai Khel : namely, to the Gigianis and Muhammadzai, Hasht- nagar; and to the Yusufzai and Mandanrs, Mardan and Swabi and the hill country adjoining.

In the next century the Mandanrs were driven from the hills by the Yusufzai, and concentrated in the east portion of the Peshawar valley, whence they in turn expelled the Yusufzai. Peshawar was included in the Mughal empire during the reigns of Akbar, Jahanglr, and Shah Jahan ; but under Aurangzeb a national insurrection was successful in freeing the Afghan tribes from the Mughal supremacy.

In 1738 the District fell into the hands of Nadir Shah; and, under his successors, Peshawar was often the seat of the Durrani court. On the death of Timur Shah in 1793, Peshawar shared the general dis- organization of the Afghan kingdom ; and the Sikhs, who were then in the first fierce outburst of revenge upon their Muhammadan enemies, advanced into the valley in 1818, and overran the whole country to the foot of the hills. In 1823 Azim Khan made a last desperate attempt to turn the tide of Sikh victories, and marched upon Peshawar from Kabul ; but he was utterly defeated by Ranjit Singh, and the whole District lay at the mercy of the conquerors. The Sikhs, however, did not take actual possession of the land, contenting themselves with the exaction of a tribute, whose punctual payment they ensured or ac- celerated by frequent devastating raids. After a period of renewed struggle and intrigue, Peshawar was reoccupied in 1834 by the Sikhs, who appointed General Avitabile as governor, and ruled with their usual fiscal severity.

In 1848 the Peshawar valley came into the possession of the British, and was occupied almost without opposition from either within or without the border. During the Mutiny the Hindustani regiments stationed at Peshawar showed signs of disaffection, and were accord- ingly disarmed with some little difficulty in May, 1857. But the 55th Native Infantry, stationed at Naushahra and Hoti Mardan, rose in open rebellion ; and on a force being dispatched against them, marched off towards the Swat hills across the frontier. Nicholson was soon in pursuit, and scattered the rebels with a loss of 120 killed and 150 prisoners. The remainder sought refuge in the hills and defiles across the border, but were hunted down by the clans, till they perished of hunger or exposure, or were brought in as prisoners and hanged or blown away from guns. This stern but necessary example prevented any further act of rebellion in the District.

Population

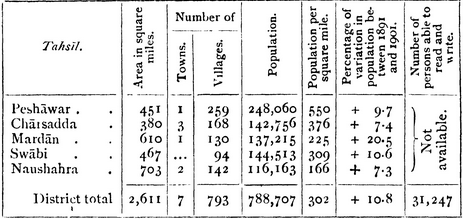

Peshawar District contains 7 towns and 793 villages. The popu- lation at each of the last three enumerations was: (1881) 599,452, Population. ( l8 9 I ) 711,795; and (1901) 788,707. It increased by nearly 11 per cent, during the last decade, the increase being greatest in the Mardan tahsil, and least in that of Nau- shahra. The District is divided into five tahsils, the chief statistics of which are given in the table on the next page.

The head-quarters of each tahsil is at the place from which it is named. The chief towns are the municipality of PESHAWAR, the administrative head-quarters of the District and capital of the Pro- vince, NAUSHAHRA, CHARSADDA, TANGI, and MARDAN. Muham- madans number 732,870, or more than 92 per cent, of the total; Hindus, 40,183; and Sikhs, 11,318. The language of the people is Pashtu.

Peshawar is as much the home of the Afghans as Kabul, and hence we find that of the total population of the District 402,000, or 51 per cent., are Pathans. They are almost entirely dependent on agriculture. Their distribution is as above described. The Khattaks are the prin- cipal tribe in the Naushahra tahsiL Among these fanatical Pathans, the Saiyids, descendants of the Prophet, who occupy a position of great influence, number 24,000. In the popular phraseology of the District, all tribes who are not Pathans are Hindkis, the most numerous being the Awans (111,000). They are found only in the Peshawar and Naushahra tahsil, and besides being very fair culti- vators are petty traders as well. Gujars (16,000) and Baghbans (9,000) are other Hindki agriculturists. These tribes are all Muham- madans. Of the trading classes, Aroras (17,000) and Khattrls (13,000) are the most important, and the Parachas (carriers and pedlars, 7,000) come next. Of the artisan classes, Julahas (weavers, 19,000), Tar- khans (carpenters, 16,000), Lohars (blacksmiths, 8,000), Kumhars (potters, 8,000), and Mochis (shoemakers and leather-workers, 5,000) are the most numerous. The Kashmiris, immigrants fiom Kashmir, number 9,000. Of the menial classes, the most important are Nais (barbers, 9,000), Dhobis (washermen, 8,000), and Chuhras and Musallis (sweepers, 8,000). The Mirasis (4,000), village minstrels and bards, and the Ghulams (300), who are chiefly engaged in domestic service and appear only in this District, are also worth mentioning. Agriculture supports 60 per cent, of the population.

The Church Missionary Society established its mission to the Afghans at Peshawar in 1855, and now has branches at Naushahra and Mardan. It organized a medical mission in 1884, and in 1894 founded the Duchess of Connaught Hospital. The Zanana Mission has a staff of five English ladies, whose work is partly medical and partly evangelistic and educational. The Edwardes Collegiate (Mission) School, founded in 1855, is now a high school with a collegiate de- partment attached.

Agriclture

With the exception of the stony tracts lying immediately below the hills, the District displays a remarkable uniformity of soil : on the surface, light and porous earth with a greater or less intermixture of sand ; and below, a substratum of strong retentive clay. The only varieties of soil are due to variations in the depth of the surface earth, or in the proportion of sand mixed with it; and with irrigation the whole valley is capable, almost without exception, of producing the richest crops. Sandy and barren tracts occur in some few localities, but they are of small extent, and bear an insignificant proportion to the total area. The spring harvest, which in 1903-4 occupied 70 per cent, of the total area cropped, is sown chiefly from the end of September to the end of January, and the autumn harvest chiefly in June, July, and August, though sugar and cotton are sown as early as March.

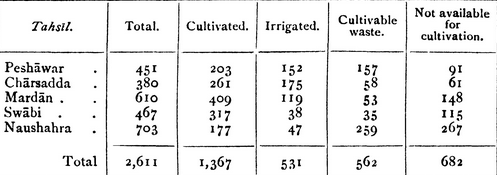

The District is held almost entirely by communities of small peasant proprietors, large estates covering only about 153 square miles. The following table shows the statistics of cultivation in 1903-4, in square miles :

The chief food-crops are wheat (555 square miles), barley (287), and maize (231). Sugar-cane (32) and cotton (26) are also of some importance. The neighbourhood of Peshawar produces apricots, peaches, pomegranates, quinces, and other fruits in great abundance; and 8-62 square miles were under fruits and vegetables in 1903-4.

The area cultivated at the settlement of 1895-6 showed an increase of 7 per cent, in the previous twenty years, largely due to the extension of canal-irrigation in the Naushahra and Peshawar tahsils. Since 1895-6 there has been a slight decrease in the cultivated area, which seems to show that the limits of the resources of the District in this respect have been reached. Little has yet been done towards improving the quality of the crops grown. Loans for the construction of wells and the purchase of plough cattle are readily appreciated by the people, and during the five years ending 1902-3 an average of Rs. 9,100 was advanced. In 1903-4 Rs. 6,460 was advanced under the Land Improvements Acts, and Rs. 5,420 under the Agriculturists' Loans Act.

Wheeled carriages are common throughout the District, though there is much pack traffic mainly carried on bullocks, which are fine strong animals, much superior to those used in agriculture. Horses are not extensively reared in the valley. The Civil Veterinary department maintains a horse and seven donkey stallions, and the District board three pony and two donkey stallions. Large flocks of sheep and goats are owned by the border villages, which have extensive grazing rights on the stony plains at the foot of the hills.

Of the total cultivated area of the District in 1903-4, 531 square miles or 40 per cent, were irrigated. Of these, 7 1 square miles were irrigated from wells, 453 from canals, and 7 from streams and tanks. In addition, 26-5 square miles, or 2 per cent., are subject to inundation. Well-irrigation is resorted to in the eastern half of the District wherever the depth of the spring-level allows. The District contains 6,389 masonry wells worked with Persian wheels by bullocks, besides 5,121 unbricked wells, lever wells, and water-lifts. The most important canals of the District are the SWAT, KABUL, and Bara River Canals. The two first are under the management of the Canal department, the last named is in charge of the Deputy-Commissioner. The Michni- Dilazak canal, taking off from the left bank of the Kabul river, and the Shabkadar branch canal from the right bank of the Swat river, belong to the District board. The District also contains a large number of private canals, which are managed by the Deputy-Commissioner under the Peshawar Canals Regulation of 1898.

There is ample historical evidence that in ancient times the District was far better wooded than it is now, and the early Chinese pilgrims often refer to the luxuriant growth of trees on hill-slopes now practically bare. The only forest at present is a square mile of military reserved ' forest ; but large areas of waste, in which the people and Government are jointly interested, have been declared ' protected ' forests. Of these, the most important is that known as the Khwarra-Zira forest in the south-east corner of the District. Fruit gardens and orchards are numerous, especially near Peshawar city.

trade and communications

The District contains quarries of slate and marble, and kankar is found in considerable quantities. Gold is washed in the Indus above Attock and in the Kabul river, but the yield is very small.

Peshawar is noted for its turbans, woven either of silk or of cotton, with silk edges and fringes; and a great deal of cotton cloth is pro- duced. Cotton fabrics, adorned with coloured wax, and known as Afrldi waxcloth,' are now turned out in large quantities for the European market. The principal woollen manufactures are felted mats and saddle-cloths, and blankets ; glazed earthenware of considerable excellence is made, and a considerable manufacture of ornamental leather-work exists. Copper- ware is largely turned out. Matting, baskets, and fans are made of the dwarf-palm.

The main trade of the District passes through the city of Peshawar, and, though of varied and not uninteresting nature, is less extensive than might perhaps have been expected. In 1903-4 the value of the trade as registered was 182-5 lakhs, of which 68 lakhs were imports. The bulk of Indian commerce with Northern Afghanistan and the countries beyond (of which Bokhara is the most important), Dlr, Swat, Chitral, Bajaur, and Buner, passes through Peshawar. The independent tribes whose territories adjoin the District are also supplied from it with those commodities which they need. Besides Peshawar city, there are bazars in which a certain amount of trade is done at Naushahra, Kalan, Hoti Mardan, Shankargarh, Tangi, Charsadda (Prang), and Rustam. The chief exports in 1903-4 were European and Indian cotton piece-goods, raw cotton, yarn, indigo, turmeric, wheat, leathern articles, manufactured articles of brass, copper and iron, salt, spices, sugar, tea, tobacco, and silver.

The transactions of the Peshawar market, however, are insignificant when compared with the stream of through traffic from the direction of Kabul and Bokhara which passes on, without stopping at Peshawar, into the Punjab and Northern India.

The main line of the North-Western Railway enters the District by the Attock bridge over the Indus, and has its terminus at Peshawar, whence an extension runs to Fort Jamrud. A branch line also runs from Naushahra through Mardan to Dargai. The District possesses 157 miles of metalled roads, of which 40 are Imperial military, 93 Im- perial civil, 17 belong to the District board, and 7 to cantonments. There are 672 miles of unmetalled roads (23 Imperial military, 123 Imperial civil, and 516 District board). The grand trunk road runs parallel with the railway to Peshawar and thence to Jamrud at the mouth of the Khyber Pass, and a metalled road from Naushahra via Mardan crosses the border from the Malakand pass into Swat. Other important roads connect Peshawar with Kohat, with Abazai, with Michni, with the Bara fort, and with Cherat. The Khyber Pass is the great highway of the trade with Kabul and Central Asia, and is guarded two days a week for the passage of caravans. The Indus, Swat, and Kabul rivers are navigable at all seasons, but are not much used for traffic. The Indus is crossed by the Attock railway bridge, which has a subway for wheeled traffic, and by three ferries. There are four bridges of boats and six ferries on the Kabul river and its branches, two bridges of boats and six ferries on the Landai, and three bridges of boats and twelve ferries on the Swat river and its branches.

Administration

The District is divided for administrative purposes into five tahsils, each under a tahsildar and naib-tahsils, except Peshawar, where there are a tahsildar and two naibs. The tahsil . .

of Mardan and Swabi form the Yusufzai subdivision, in charge of an Assistant Commissioner whose head-quarters are at Mardan, the home of the famous Corps of Guides. This officer is entrusted, under the orders of the Deputy-Commissioner, with the political supervision of Buner and the Yusufzai border. European officers with the powers of subdivisional officers are in charge of Peshawar city, and of the Charsadda and Naushahra tahsil. The Deputy-Commissioner is further assisted by an Assistant Commissioner, who is in command of the border military police. There are also three Extra- Assistant Commissioners, one of whom has charge of the District treasury. The District Judge and the Assistant Commissioner at Mardan have the powers of Additional District Magistrates.

The Deputy-Commissioner as District Magistrate is responsible for the criminal work of the District ; civil judicial work is under a District Judge, and both are supervised by the Divisional and Sessions Judge of the Peshjiwar Civil Division. The Assistant Commissioner, Mardan, has the powers of a Subordinate Judge, and in his civil capacity is under the District Judge, as also are two Munsifs, one at head-quarters and one at Mardan. There is one honorary Munsif at Peshawar. The Cantonment Magistrate at Peshawar is Small Cause Court Judge for petty civil cases within cantonment limits. The criminal work of the District is extremely heavy, serious crime being common. The Frontier Crimes Regulation is in force, and many cases are referred to the decision of councils of elders. Civil litigation is not abnormally frequent. Important disputes between Pathan families of note are, when possible, settled out of court by councils of elders under the control of the Deputy-Commissioner. The commonest type of civil suit is based on the claim of reversionary heirs to annul alienations of lands made by widows and daughters of deceased sonless proprietors, as being contrary to custom.

The plain south of the Kabul river and the rich dodb between the Kabul and Swat rivers have always been under the control of the central government of the time, while the Khattak hills and the great plain north of the Swat and Kabul rivers have generally been independent.

In 1834 the Sikhs finally gained a firm hold on the doab and the tract south of the Kabul river. They imposed a full assessment and collected it through the leading men, to whom considerable grants were made. The Sikh collections averaged 6 1/2 lakhs from 1836 to 1842, compared with 5 lakhs under the Durranis. These figures exclude the revenues of Yusufzai and Hashtnagar, which are also excluded from the first summary settlement, made in 1849-50, when the demand was 10 lakhs. Yusufzai was settled summarily in 1847 and Hashtnagar in 1850.

In 1855 a new settlement was made for the whole District. It gave liberal reductions in Peshawar, the doab, Daudzai, and Naushahra, where the summary assessment, based on the Sikh demands, had been very high, while the revenue in Yusufzai was enhanced. The net result was a demand of less than 8 lakhs. This assessment was treated as a summary one, and a regular settlement was carried out between 1869 and 1875, raising the revenue to 8 lakhs. The settlement worked well, particularly in those villages where a considerable enhancement was made, the high assessment acting as a stimulus to increased effort on the part of the cultivators. The revenue, however, was recovered with the greatest difficulty ; and the history of the settlement has been described as one continuous struggle on the part of the tahsildar to recover as much, and on the part of the landowners to pay as little, of the revenue demand as possible. This was due to the character and history of the people, and does not reflect at all on the pitch of the assessment. The latest revision began in 1892 and was finished in 1896.

The chief new factors in the situation were the opening of the Swat and the Kabul River Canals, the development of communications in 1882 by means of the railway, the rise in prices, and the increase in prosperity due to internal security. Assessed at half the net ' assets ', the demand would have amounted to 23 3/4 lakhs, or Rs. 2-7-7 per cultivated acre. The revenue actually imposed was slightly more than ii lakhs, an increase of about 2 1/3 lakhs, or 28 per cent., on the former demand. Of the total revenue Rs. 1,89,000 is assigned, compared with Rs. 1,76,000 at the regular settlement. The incidence per culti- vated acre varies from Rs. 1-11-4 in Charsadda to R. 0-8-8 in Mardan.

Frontier remissions are a special feature of the revenue administra- tion. A portion of the total assessment of a border estate is remitted, in consideration of the responsibility of the proprietors for the watch and ward of the border. The remissions are continued during the pleasure of Government, on condition of service and good conduct.

The collections of total revenue and of land revenue alone are shown below, in thousands of rupees :

PESHAWAR CITY is the only municipality. Outside this local affairs are managed by a District board, whose income is mainly derived from a local rate. In 1903-4 the income of the board was Rs. 1,15,000, and the expenditure Rs. 1,21,000, public works forming the largest item.

The regular police numbers 1,265 of all ranks, of whom 210 are cantonment and 277 municipal police. There are 27 police stations and 20 road-posts. The police force is under the control of a Super- intendent, who is assisted by three European Assistant Superintendents ; one of these is in special charge of Peshawar city, while another is stationed at Mardan.

The border military police numbers 544 men, under a commandant who is directly subordinate to the Deputy-Commissioner. They are entirely distinct from the regular police. The posts are placed at convenient distances along the frontier ; and the duty of the men is to patrol and prevent raids, to go into the hills as spies and ascertain generally what is going forward. The system is not in force on the Yusufzai border, as the tribes on that side give little or no trouble. The District jail at head-quarters can accommodate 500 prisoners.

Since 1891 the population has actually gone back in literacy, and in 1901 only 4 per cent. (6-5 males and o-1 females) could read and write. The reason is that indigenous institutions are decreasing in number every year owing to the lack of support, while public in- struction at the hands of Government has failed as yet to become popular. The influence of the Mullas, though less powerful than it used to be, is still sufficient to prevent the attendance of their co- religionists at Government schools. The education of women has, however, made some progress. This is due in a large measure to the exertions of lady missionaries, who visit the zandnas and teach the younger women to read Urdu, Persian, and even English. The number of pupils under instruction was 1,833 in 1880-1, 1.0,655 m 1890-1, 9,242 in 19001, and 10,036 in 1903-4. In the latest year there were 10 secondary and 78 primary (public) schools, and 30 advanced and 208 elementary (private) schools, with 64 girls in public and 755 in private institutions. Peshawar city contains an unaided Arts college and four high schools. The total expenditure on education in 1903-4 was Rs. 61,000, to which District funds contributed Rs. 25,000, the Peshawar municipality Rs. 6,400, and fees Rs. 14,700.

Besides . the Egerton Civil Hospital and four dispensaries in Peshawar city, the District has five outlying dispensaries. In these institutions there are 133 beds for in-patients. In 1904 the number of cases treated was 202,793, including 2,980 in-patients, and 9,290 operations were performed. The income amounted to Rs. 27,600, which was contributed by municipal funds and by the District board equally. The Church Missionary Society maintains a Zanana Hospital, named after the Duchess of Connaught, which is in charge of a qualified European lady. The number of successful vaccinations in 1903-4 was 24,000, representing 33 per 1,000 of the population.

[J. G. Lorimer, District Gazetteer (1897-8).]