Pondicherry (Puducherry)

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

Arikamedu

History & Significance: Arikamedu

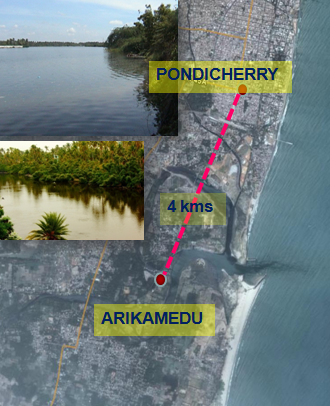

Arikamedu is situated at the estuary of Ariyankuppam River and Bay of Bengal, the place is 4 km from Puducherry,Arikamedu is the earliest known settlement dating perhaps from the 2nd century BC, inhabited by people whose pottery relates to the Iron-age (megalithic) cultures of south India. The town extends along the banks of the River Ariyankuppam which is believed to be a navigable river during the 17th / 18th century and this led to Arikamedu becoming a major market town with maritime contacts between ancient India and Rome

M o rt i m e r Wheeler was the first to excavate at Arikamedu in 1945 and confirm that the fishing village was once a major Chola port that flourished for centuries by trading with the Romans. Later, Frenchman JM Casal (1947) and Vimala Begley of the University of Pennsylvania (1989-1992) conducted excavations.

The excavations display

1.The site had an established trade link between the Indian subcontinent and Mediterranean counties. 2.The inhabitants used to import goods (primarily from Mediterranean basin) such as Amphora, wines, Olive oil, ceramic items like Sigillata etc. Clothes(muslin).spices and beads were exported from this port.

3.Due to some natural calamities and other unforeseen reasons, the Arikamedu site was left unattended and the buildings became remains of history.

4.The Historic remains were declared as National Heritage Assets under the Ancient Monuments and Archeological Sites and Remains Act, (AMASR) 1958, and the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) maintained it.

Towards the end of the 18th century the site was briefly occupied . In 1771-73 a seminary and residence was built for the Jesuit missionaries. The seminary was abandoned in 1783. The ruins of the seminary still survives and is known as Miss*ion House , which today is the only visible structure in the Arikamedu archeological site .

[[File: Visual Appraisal Of The Site.png| Visual Appraisal Of The Site |frame|left|500px]

Ossudu Lake

The qualities and opportunities

Location

1.Ousteri (or Oussudu) Lake is the largest lake in Pondicherry,8 sqkm water spread area-3.9 sqkm within Puducherry, located approximately 19 kms west of the town.

Visual / Scenic & Recreational

1.Presence of land running through the length of the Lake Bund which can be visually exploited. 2.Native vegetation trees, shrubs and undergrowth are ideally distributed around the periphery of the lake. 3.Quality and clarity of stored water a visually striking element may be reinforced with de-silting and removal of weeds.

Ecological

1.The Bombay Natural History Society, a member of Birdlife International, has designated Ousteri an Important Bird Area (IBA) of India – over 20,000 birds belonging to over 40 species used to reside or winter at Ousteri.

2.The Asian Wetland Bureau declared Ousteri one of 93 significant wetlands in Asia; and many of the birds recorded at Ousteri, including Spot-billed pelicans, Eurasian Spoonbills, Darters, Painted Storks, and Black-headed (or White) Ibis, are on the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species.

3.This lake was one of the largest breeding sites for the Common Coot in South India, and many of the resident birds, such as the Purple Moorhen and Little Grebe, nested amidst floating vegetation present in the lake

Pondicherry

Puducheri, Pulcheri

The chief of the French Settlements in India, the capital of which, a town of the same name, is the head-quarters of their Governor. The town is situated on the Coromandel coast in 11degree 56' N. and 79degree 49' E., about 12 miles north of Cuddalore. It lies on the road leading from Madras to Cuddalore, and is the terminus of the Villupuram-Pondicherry branch of the South Indian Railway. The distance from Madras to Pondicherry is 122 miles by rail and 105 by road. The area of the Settlement is 115 square miles, and its population in 1901 numbered 174,456. It consists of the four communes of Pondicherry, Oulgaret, Villenour, and Bahur. The population of the town of Pondicherry in the same year was 27,448, of whom 12,904 were males and 14,544 females. Hindus numbered 14,544 and Christians 7,247, most of the latter being Roman Catholics. The history of the place is given in the article on the FRENCH POSSESSIONS. The Settlement was founded in 1674 under Francois Martin. In 1693 it was captured by the Dutch, but was restored in 1699. It was besieged four times by the English. The first siege under Admiral Boscawen in 1748 was unsuccessful. The second, under Eyre Coote in 1761, resulted in the capture of the place, which was restored in 1765. It was again besieged and captured in 1778 by Sir Hector Munro, and the fortifications were demolished in 1779. The place was again restored in 1785 under the Treaty of Versailles of 1783. It was captured a fourth time by Colonel Braithwaite in 1793, and finally restored in 1816.

The Settlement comprises a number of isolated pieces of territory which are cut off from the main part and surrounded by the British District of South Arcot, except where they border on the sea. This fact occasions considerable difficulty in questions connected with crime, land customs, and excise. The Collector of South Arcot is empowered to deal with ordinary correspondence with the French authorities on these and kindred matters, and in this capacity is styled the Special Agent, At Pondicherry itself is a British Consular Agent accredited to the French Government, who is usually an officer of the Indian Army. The town is compact, neat, and clean, and is divided by a canal into two parts, the Ville blanche and the Ville noire. The Ville blanche has a European appearance, the streets being laid at right angles to one another, with trees along their margins reminding the visitor of conti- nental boulevards, and the houses being constructed with courtyards and embellished with green Venetians. All the cross streets lead down to the shore, where a wide promenade facing the sea is again different

from anything of its kind in British India. In the middle is a screw-pile pier which serves, when ships touch at the port, as a point for the landing of cargo and, on holidays, as a general promenade for the population. There is no real harbour at Pondicherry ; ships lie at a distance of about a mile from the shore, and communication with them is conducted by the usual masula boats of this coast. Facing the shore end of the pier is a statue of the great Dupleix, to whom the place and the French name owed so much. It is surrounded by a group of carved stone columns which are said to have been brought from the ruins of the celebrated fort of GINGEE. Behind is the Place Dupleix (or Place de la Republique) with a band-stand ; and west again of this the Place du Gouvernement, a wide extent of grass with a fountain in the middle of it, round which stand the chief buildings of the town, including Government House, the Hotel de Ville, the High Court, and the barracks. Other erections in the town are the Secretariat, the Cathedral of Notre Dame des Anges, the college of the Missions trangeres, the Calve college, two clock-towers, a lighthouse, the hospital, and the jail. The town alsq contains a public library of about 16,000 volumes, and public gardens with a small collection of wild animals and birds.

Pondicherry was made a municipality in 1880, with a mayor and a council of eighteen members. The receipts and expenditure of this body during the ten years ending 1902 averaged Rs. 47,000. There is no drainage system ; but the water-supply is excellent, being derived from a series of artesian wells, which are one of the features of the place. Until they were discovered, about the middle of last century, the only source of supply was from ordinary wells sunk within the town. The best of the present artesian sources is at Mudrapalaiyam, from which pipes have been taken to reservoirs in the market and the Place du Gouvernement. The roads of the town are kept in excellent order. The ordinary means of locomotion is the well-known ‘push-push’, 'which is pushed and pulled by two men. The chief educational institutions are a college belonging to the Missions Etrangeres, which teaches up to the B.A. standard in French, and the Calve college, a non-denominational institution in which both Europeans and natives receive instruction up to the Matriculation. The latter is affiliated to the Madras University. The industries of Pondicherry consist chiefly of weaving. The Patnul- karans, a Gujarati caste of weavers, make a kind of zephyr fabric which is much used locally and is also exported largely to Singapore. Cotton stuffs are also woven by machinery in the Rodier, Savana, and Gaebele mills. A new industry is the manufacture of cocotine, a substitute for ghi, at the Sainte Elisabeth factory. The total value of the imports by sea in 1904 was 179,000, and of the exports 1,102,000, of which 27,000 and 435,000 respectively were brought from and sent to France or French colonies. The principal imports are wines and spirits and areca-nuts, but the total is made up of a number of items of which none is individually important. The exports mainly consist of ground- nut kernels and oil ; but cotton fabrics, coco-nut oil, and rice are also items of importance. The boats of the Messageries Maritimes Company call regularly at the port.

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

The Vietnam connection

Professor Ananya Jahanara Kabir’s research

Adrija Roychowdhury, March 5, 2025: The Indian Express

When Professor Ananya Jahanara Kabir visited Pondicherry in 2019, her plan was to dig into the creole culture present in the city that once belonged to the erstwhile French colony. She set out to find traces of the influence that the French left behind, be it in terms of food, language, music, dance or just the general way of life. What came as a surprise however, was a perceptible and yet ignored presence of Vietnam in the memories and family histories of almost every Franco-Pondicherrian she met.

Ananya, who teaches English Literature at King’s College London, has been researching and theorising about creole communities in India, or rather cultures that are a product of unexpected encounters between the European and non-European worlds. In the midst of her research endeavour, Vietnam came out of the blue, and opened a whole new Pandora’s box.

Vietnam is like a “public secret” in Pondicherry, says Ananya. Almost every person seems to have a Vietnam connection and it is an extremely important part of the Franco-Pondicherrian understanding of who they are and their relationship to ‘Frenchness’. “It is so ubiquitous that it is actually quite startling how with this extreme imbrication of Vietnamese people in families, this memory is not much more public,” she says.

In research article titled, Creolising Archipelagic Intimacies: Remembering India and Vietnam via Pondicherry (spring 2025), Ananya has presented her findings from the investigations into the paradoxical Vietnamese presence in Pondicherrian lives: one which is both overbearingly present and yet almost invisible. In her conversation with indianexpress.com, she explained the complex colonial history that ties Vietnam to Pondicherry and the many residues it has left behind.

Can you give us a few examples of how Vietnam’s memory is preserved in Pondicherry?

Firstly, we have to think about Pondicherry itself in two ways. We have to think about Pondicherry as a material space, a geographic site, and a topography. It sits there. It’s a city. It’s got its monuments. It’s got its people, restaurants, churches, cemeteries, and more.

But we also have to think of Pondicherry as a diasporic space, both spatially located in Pondicherry itself, but also floating around in its diasporas. So we’re going to think about the Franco-Pondicherrians who are carrying parts of Pondicherry with them in France as well as other parts of the world.

The memory of Vietnam links these two kinds of Pondicherrian spaces together and creates a bigger frame. These memories, most importantly, are those of food. Because a lot of Franco-Pondicherrians regularly incorporate Vietnamese food in their cuisine, it will be cooked anywhere they live. It doesn’t have to be located within Pondicherry itself. For instance, there is the version of Vietnamese spring rolls which are called nem or chaiyo by Pondicherrians after cha gio, the terms used in South Vietnam. This favourite Franco-Pondicherrian snack is served at social gatherings worldwide.

You will also find a strong presence of Vietnam in the cemeteries. If you go to the big cemeteries, the graveyards of Pondicherry people, you will find on the tombstones details of where people were born and where they died. And you will see Saigon or other places of Vietnam regularly inscribed on the tombstones. If you go to the churches, you will find statues and other donations from people who once lived in Saigon.

There are other subtle traces of Vietnam in Pondicherry’s memory — for instance, in the way people arrange their homes. I had come across this comment by a Vietnamese student who was in India for an exchange programme, wherein he said that whenever he entered the homes of Franco-Pondicherrian people he was reminded of the interiors of Vietnamese homes. There is a guest house in Pondicherry, Le Jardin Suffren. The reception area there is decorated with photographs of family members from Vietnam and paraphernalia like dragon motifs on the wall which are Southeast Asian.

The French colonial world included several other places apart from Vietnam, such as parts of Africa. Why is it that it is only Vietnam that made its way to Pondicherrian memory and not other parts of the empire?

To be honest, other parts of the French empire are also there. And this could be another project. In my article I have mentioned about people from Pondicherry travelling to places like Senegal and North Africa for work. That’s a whole other project and it’s worth working on. I chose to focus on the Vietnamese connection, because it’s the one that first floated up for me.

But you may as well ask why out of all these layers of connections, the Vietnamese one is the one that floats up first. I think it’s perhaps because Pondicherry and Vietnam are two parts of the French empire that are within the Indian Ocean world.

Once the British took over India after the Anglo-French wars in the south, the French presence in India was gradually reduced to the enclaves of Pondicherry, Karikal, Yanam, Mahe, and Chandernagore. And they were not allowed to expand more. You have got to imagine that the French have lost real mobilising power in India, with a base but little else. So they were looking to see where they could go next and they found a fresh opening in Southeast Asia. They took over what they called “l’Indochine or ‘Indo-China’– basically it consisted of present-day Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos.

When the French took over Indochina, they had to send people there to administer the new colony. Instead of sending a shipload of people all the way from France, they just simply started creating a little circuit in Asia itself, between Pondicherry and Saigon and other parts, other locations of Indochina. Consequently, they started encouraging people from Pondicherry to fill the administrative gap in Vietnam. Historian Natasha Pairaudeau in her book Mobile Citizens: French Indians in Indochina, 1858-1955 writes exactly about this: Why did so many Pondicherrians get linked to the French Empire in Southeast Asia?

A Franco-Pondicherrian agricultural scientist, the late Claude Maurius, whose memoir I have referred to, calls Indochina an “opening” because it represented, literally, a career opportunity for a whole bunch of people who had become French and were looking for new ways to express their Frenchness.

Was it just the bureaucrats who travelled from Pondicherry to Vietnam?

Once you had bureaucrats travelling along with their families, you would need a whole infrastructure to support them. So different kinds of people started travelling, sensing the opportunities. They included businessmen, jewellers, and bakers. In fact a whole caste of milkmen were taken along. Southeast Asians are known to be lactose intolerant and do not have a milk culture. So in order to meet with the requirements of the French and the Indians, people who deal with cows, and perhaps even the cows were sent across.

Therefore it was not just a small creamy layer of people who migrated, but four or five different groups of people. Natasha Pairaudeau in her work calls it a four-tiered diaspora that emerged. So there were merchants, bureaucrats, military men and finally the blue-collared workers, including those who were supplying milk.

There was also the non-Franco-Pondicherrian lot who migrated, following those from Pondicherry, for example merchants and small-scale service providers looking for economic opportunities. In fact, I begin my article by reminding readers that the notorious Charles Sobhraj too had a Vietnamese mother and a Sindhi father.

You mention celebrated figures like singer Julie Quang, stunt coordinator Peter Hein, and the notorious serial killer Charles Sobhraj, who are all partly Vietnamese and Indian. And yet their mixed genealogy is almost invisible in public discussions. Why do you think that has happened?

We in India have a consciousness of ourselves as an ex-colony of the British. So stories and communities that are remnant of the British presence in India are easier to remember and understand. Thus, for instance, everybody in India would have an idea of who an Anglo-Indian person is. But they wouldn’t know much about the kinds of demographics and communities created through the French presence in India, including those with Vietnamese connections. Our memories collectively accept that textbook fact that for two hundred years we were a British colony.

Already within this framework the French colonial presence is pretty marginalised. And whatever we know of it is mainly because of heritage tourism which has become a big thing lately. What really shattered the links of memory between Vietnam and French India and later Pondicherry of the Indian republic, was the fact that all these spaces were involved in complex decolonisation processes of their own. On the Indian side, for instance, there was no need for an Indo-Vietnamese story because it just didn’t fit into the story about how we emerged out of anti-colonial resistance to British Rule.

There is a big picture of British India, within that there are smaller pictures of Portuguese India and French India, and then within them there are mosaics of inner stories, such as the Franco-Tamlians in Vietnam or similarly the Goans who went to East Africa. The point is that nobody found it necessary to publicise the stories of these numerically smaller groups.

What is the memory of Pondicherry in Vietnam?

That would be the next step of this research project. We know that there are Tamil temples located there, for instance the Mariamman Temple at Saigon. We do know that in Vietnamese restaurants anywhere in the world, they always have a Vietnamese curry. The Vietnamese chicken curry, ‘ca ri ga’, is definitely a result of Indian influence in Vietnam. Even the curry powder that they have created is called ‘ca ri an do’ (Indian curry).

Of course, there is also an anti-Indian element in the local Vietnamese memory. It happened in so many other parts of the Indian Ocean world where Indians were present as important minorities because they were fitted into the colonial system, be it the Portuguese colonial system, the British, or the French. Pairaudeau examines in detail how cartoons and pamphlets presented Vietnamese ladies rejecting the Tamil milkman in favour of the new tinned condensed milk being supplied by companies like Nestlé. It is fascinating that the milkman who came all the way from Pondicherry became caught in the evolving relationship between European taste, industrialisation, and the Vietnamese people.