Pulluvan

This article is an excerpt from Government Press, Madras |

Pulluvan

The Pulluvans of Malabar are astrologers, medicine-men, priests and singers in snake groves. The name is fancifully derived from pullu, a hawk, because the Pulluvan is clever in curing the disorders which pregnant women and babies suffer from through the evil influence of these birds. The Pulluvans are sometimes called Vaidyans (physicians). As regards the origin of the caste, the following tradition is narrated. Agni, the fire god, had made several desperate but vain efforts to destroy the great primeval forest of Gāndava. The eight serpents which had their home in the forest were the chosen friends of Indra, who sent down a deluge, and destroyed, every time, the fire which Agni kindled in order to burn down the forest. Eventually Agni resorted to a stratagem, and, appearing before Arjunan in the guise of a Brāhman, contrived to exact a promise to do him any favour he might desire.

Agni then sought the help of Arjunan in destroying the forest, and the latter created a wonderful bow and arrows, which cut off every drop of rain sent by Indra for the preservation of the forest. The birds, beasts, and other creatures which lived therein, fled in terror, but most of them were overtaken by the flames, and were burnt to cinders. Several of the serpents also were overtaken and destroyed, but one of them was rescued by the maid-servant of a Brāhman, who secured the sacred reptile in a pot, which she deposited in a jasmine bower. When the Brāhman came to hear of this, he had the serpent removed, and turned the maid-servant adrift, expelling at the same time a man-servant, so that the woman might not be alone and friendless. The two exiles prospered under the protection of the serpent, which the woman had rescued from the flames, and became the founders of the Pulluvans. According to another story, when the great Gāndava forest was in conflagration, the snakes therein were destroyed in the flames. A large five-hooded snake, scorched and burnt by the fire, flew away in agony, and alighted at Kuttanād, which is said to have been on the site of the modern town of Alleppey. Two women were at the time on their way to draw water from a well.

The snake asked them to pour seven potfuls of water over him, to alleviate his pain, and to turn the pot sideways, so that he could get into it. His request was complied with, and, having entered the pot, he would not leave it. He then desired one of the women to take him home, and place him in a room on the west side of the house. This she refused to do for fear of the snake, and she was advised to cover the mouth of the pot with a cloth. The room, in which the snake was placed, was ordered to be closed for a week. The woman’s husband, who did not know what had occurred, tried to open the door, and only succeeded by exerting all his strength. On entering the room, to his surprise he found an ant-hill, and disturbed it. Thereon the snake issued forth from it, and bit him. As the result of the bite, the man died, and his widow was left without means of support. The snake consoled her, and devised a plan, by which she could maintain herself. She was to go from house to house, and cry out “Give me alms, and be saved from snake poisoning.”

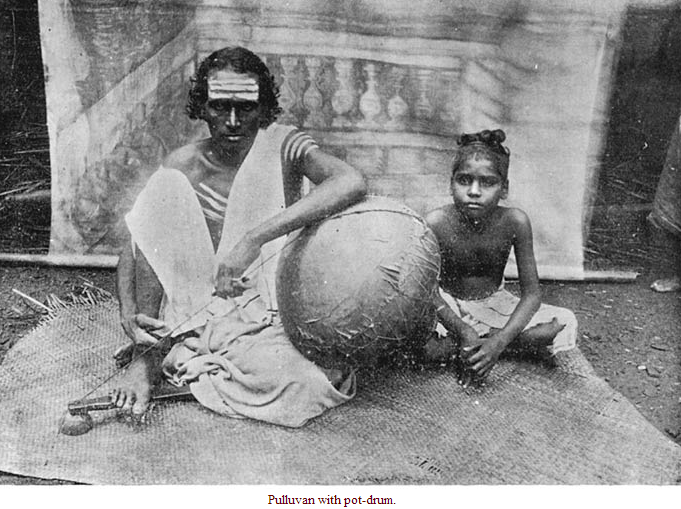

The inmates would give, and the snakes, which were troubling their houses, would cease from annoying them. For this reason, a Pulluvan and his wife, when they go with their pulluva kudam (pot-drum) to a house, are asked to sing, and given money.

The Pulluvar females, Mr. T. K. Gopal Panikkar writes, “take a pretty large pitcher, and close its opening by means of a small circular piece of thin leather, which is fastened on to the vessel by means of strings strongly tied round its neck. Another string is adjusted to the leather cover, which, when played on by means of the fingers, produces a hoarse note, which is said to please the gods’ ears, pacify their anger, and lull them to sleep.” In the Malabar Gazetteer, this instrument is thus described. “It consists of an earthenware chatty with its bottom removed, and entirely covered, except the mouth, with leather. The portion of the leather which is stretched over the bottom of the vessel thus forms a sort of drum, to the centre of which a string is attached. The other end of the string is fixed in the cleft of a stick. The performer sits cross-legged, holding the chatty mouth downwards with his right hand, on his right knee. The stick is held firmly under the right foot, resting on the left leg. The performer strums on the string, which is thus stretched tight, with a rude plectrum of horn, or other substance.

The vibrations communicated by the string to the tympanum produce a curious sonorous note, the pitch of which can be varied by increasing or relaxing the tension of the string.” This musical instrument is carried from house to house in the daytime by these Pulluvar females; and, placing the vessel in a particular position on the ground, and sitting in a particular fashion in relation to the vessel, they play on the string, which then produces a very pleasant musical note. Then they sing ballads to the accompaniment of these notes. After continuing this for some time, they stop, and, getting their customary dues from the family, go their own way. It is believed that the music, and the ballads, are peculiarly pleasing to the serpent gods, who bless those for whose sakes the music has been rendered.” The Pulluvans also play on a lute with snakes painted on the reptile skin, which is used in lieu of parchment. The skin, in a specimen at the Madras Museum, is apparently that of the big lizard Varanus bengalensis. The lute is played with a bow, to which a metal bell is attached. The dwelling-houses of the Pulluvans are like those of the Izhuvans or Cherumas. They are generally mud huts, with thatched roof, and a verandah in front.

When a girl attains maturity, she is placed apart in a room. On the seventh day, she is anointed by seven young women, who give an offering to the demons, if she is possessed by any. This consists of the bark of a plantain tree made into the form of a triangle, on which small bits of tender cocoanuts and little torches are fixed. This is waved round the girl’s head, and floated away on water. As regards marriage, the Pulluvans observe both tāli-kettu and sambandham. In the vicinity of Palghat, members of the caste in the same village intermarry, and have a prejudice against contracting alliances outside it. Thus, the Pulluvans of Palghat do not intermarry with those of Mundūr and Kanghat, which are four and ten miles distant. It is said that, in former days, intercourse between brother and sister was permitted. But, when questioned on this point, the Pulluvans absolutely deny it. It is, however, possible that something of the kind was once the case, for, when a man belonging to another caste is suspected of incest, it is said that he is like the Pulluvans. Should the parents of a married woman have no objection to her being divorced, they give her husband a piece of cloth called murikotukkuka. This signifies that the cloth which he gave is returned, and divorce is effected.

The Pulluvans follow the makkathāyam law of inheritance (from father to son). But they seldom have any property to leave, except their hut and a few earthen pots. They have their caste assemblies (parichas), which adjudicate on adultery, theft, and other offences. They believe firmly in magic and sorcery, and every kind of sickness is attributed to the influence of some demon. Abortion, death of a new-born baby, prolonged labour, or the death of the woman, fever, want of milk in the breasts, and other misfortunes, are attributed to malignant influences. When pregnant women, or even children, walk out alone at midday, they are possessed by them, and may fall in convulsions. Any slight dereliction, or indifference with regard to the offering of sacrifices, is attended by domestic calamities, and sacrifices of goats and fowls are requisite.

More sacrifices are promised, if the demons will help them in the achievement of an object, or in the destruction of an enemy. In some cases the village astrologer is consulted, and he, by means of his calculations, divines the cause of an illness, and suggests that a particular disease or calamity is due to the provocation of the family or other god, to whom sacrifices or offerings have not been made. Under these circumstances, a Velichapād, or oracle, is consulted. After bathing, and dressing himself in a new mundu (cloth), he enters on the scene with a sword in his hand, and his legs girt with small bells. Standing in front of the deity in pious meditation, he advances with slow steps and rolling eyes, and makes a few frantic cuts on his forehead. He is already in convulsive shivers, and works himself up to a state of frenzied possession, and utters certain disconnected sentences, which are believed to be the utterances of the gods.

Believing them to be the means of cure or relief from calamity, those affected reverentially bow before the Velichapād, and obey his commands. Sometimes they resort to a curious method of calculating beforehand the result of a project, in which they are engaged, by placing before the god two bouquets of flowers, one red, the other white, of which a child picks out one with its eyes closed. Selection of the white bouquet predicts auspicious results, of the red the reverse. A man, who wishes to bring a demon under his control, must bathe in the early morning for forty-one days, and cook his own meals. He should have no association with his wife, and be free from all pollution. Every night, after 10 o’clock, he should bathe in a tank (pond) or river, and stand naked up to the loins in the water, while praying to the god, whom he wishes to propitiate, in the words “I offer thee my prayers, so that thou mayst bless me with what I want.” These, with his thoughts concentrated on the deity, he should utter 101, 1,001, and 100,001 times during the period. Should he do this, in spite of all obstacles and intimidation by the demons, the god will grant his desires. It is said to be best for a man to be trained and guided by a guru (preceptor), as, if proper precautions are not adopted, the result of his labours will be that he goes mad.

A Pulluvan and his wife preside at the ceremony called Pāmban Tullal to propitiate the snake gods of the nāgāttān kāvus, or serpent shrines. For this, a pandal (booth) is erected by driving four posts into the ground, and putting over them a silk or cotton canopy. A hideous figure of a huge snake is made on the floor with powders of five colours. Five colours are essential, as they are visible on the necks of snakes. Rice is scattered over the floor. Worship is performed to Ganēsa, and cocoanuts and rice are offered. Incense is burnt, and a lamp placed on a plate. The members of the family go round the booth, and the woman, from whom the devil has to be cast out, bathes, and takes her seat on the western side, holding a bunch of palm flowers. The Pulluvan and his wife begin the music, vocal and instrumental, the woman keeping time with the pot-drum by striking on a metal vessel. As they sing songs in honour of the snake deity, the young female members of the family, who have been purified by a bath, and are seated, begin to quiver, sway their heads to and fro in time with the music, and the tresses of their hair are let loose. In their state of excitement, they beat upon the floor, and rub out the figure of the snake with palm flowers. This done, they proceed to the snake-grove, and prostrate themselves before the stone images of snakes, and recover consciousness. They take milk, water from a tender cocoanut, and plantains. The Pulluvan stops singing, and the ceremony is over. “Sometimes,” Mr. Gopal Panikkar writes, “the gods appear in the bodies of all these females, and sometimes only in those of a select few, or none at all. The refusal of the gods to enter into such persons is symbolical of some want of cleanliness in them: which contingency is looked upon as a source of anxiety to the individual.

It may also suggest the displeasure of these gods towards the family, in respect of which the ceremony is performed. In either case, such refusal on the part of the gods is an index of their ill-will or dissatisfaction. In cases where the gods refuse to appear in any one of those seated for the purpose, the ceremony is prolonged until the gods are so properly propitiated as to constrain them to manifest themselves. Then, after the lapse of the number of days fixed for the ceremony, and, after the will of the serpent gods is duly expressed, the ceremonies close.” Sometimes, it is said, it may be considered necessary to rub away the figure as many as 101 times, in which case the ceremony is prolonged over several weeks. Each time that the snake design is destroyed, one or two men, with torches in their hands, perform a dance, keeping step to the Pulluvan’s music. The family may eventually erect a small platform or shrine in a corner of their grounds, and worship at it annually. The snake deity will not, it is believed, manifest himself if any of the persons, or articles required for the ceremony, are impure, e.g., if the pot-drum has been polluted by the touch of a menstruating female. The Pulluvan, from whom a drum was purchased for the Madras Museum, was very reluctant to part with it, lest it should be touched by an impure woman.

The Pulluvans worship the gods of the Brāhmanical temples, from a distance, and believe in spirits of all sorts and conditions. They worship Velayuthan, Ayyappa, Rāhu, Mūni, Chāthan, Mukkan, Karinkutti, Parakutti, and others. Mūni is a well-disposed deity, to whom, once a year, rice, plantains, and cocoanuts are offered. To Mukkan, Karinkutti, and others, sheep and fowls are offered. A floral device (padmam) is drawn on the floor with nine divisions in rice-flour, on each of which a piece of tender cocoanut leaf, and a lighted wick dipped in cocoanut oil, are placed. Parched rice, boiled beans, jaggery (crude sugar), cakes, plantains, and toddy are offered, and camphor and incense burnt. If a sheep has to be sacrificed, boiled rice is offered, and water sprinkled over the head of the sheep before it is killed. If it shakes itself, so that it frees itself from the water, it is considered as a favourable omen. On every new-moon day, offerings of mutton, fowls, rice-balls, toddy, and other things, served up on a plantain leaf, are made to the souls of the departed. The celebrants, who have bathed and cooked their own food on the previous day, prostrate themselves, and say “Ye dead ancestors, we offer what we can afford. May you take the gifts, and be pleased to protect us.” The Pulluvans bury their dead. The place of burial is near a river, or in a secluded spot near the dwelling of the deceased. The corpse is covered with a cloth, and a cocoanut placed with it. Offerings of rice-balls are made by the son daily for fifteen days, when pollution ceases, and a feast is held.

At the present day, some Pulluvans work at various forms of labour, such as sowing, ploughing, reaping, fencing, and cutting timber, for which they are paid in money or kind. They are, in fact, day-labourers, living in huts built on the waste land of some landlord, for which they pay a nominal ground-rent. They will take food prepared by Brāhmans, Nāyars, Kammālans, and Izhuvas, but not that prepared by a Mannān or Kaniyan. Carpenters and Izhuvas bathe when a Pulluvan has touched them. But the Pulluvans are polluted by Cherumas, Pulayas, Paraiyans, Ullādans, and others. The women wear the kacha, like Izhuva women, folded twice, and worn round the loins, and are seldom seen with an upper body-cloth.