Punjab: Political history

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Anti- establishment impulses

Till 2023 February

Sarju Kaul, February 27, 2023: The Times of India

The clashes between supporters of radical Sikh preacher Amritpal Singh and the police in Amritsar last week have echoes of Punjab’s bloody past. But what explains the antiestablishment streak in Punjabi society? Punjabis, especially Sikhs, value courage and spirit of resistance. It is this sentiment that drives their support to all causes and protests, which essentially at an organic level are a battle against governments and their policies. Historical and religious roots

This reverence for resistance and courage to stand up to powerful governments have geographical, historical and religious roots. Pre-Partition Punjab was at the forefront of resistance to invaders, adventure-seekers and colonial powers from Alexander of Macedonia to the British. And this spirit of standing up to intruders was honed by the supreme sacrifices of the Sikh Gurus while facing off with the rulers at the time. As the saying goes, Punjab is never in sync with Delhi. This was encapsulated in the yearlong farm struggle on the borders of Delhi, in which every strata of Punjabi society, regardless of their affiliation, supported the campaign against the nowwithdrawn three central laws with donations of funds, material and time.

This intrinsic knowledge that Sikhs are the only community who will stand by your side when dealing with police, courts and government is there among all the people in Punjab. Unique synergy between religion and politics, encapsulated in Guru Hargobind Singh’s doctrine of ‘MiriPiri’, also drives the resistance against any injustice, with causes ranging from the sudden demolition of houses in a Jalandhar locality to no justice in the 2015 cases of sacrilege and police firing.

Guru Gobind Singh’s foundation of Khalsa Panth and his espousal of armed resistance even as his four sons – Sahibzadas Ajit Singh, Jujhar Singh, Zorawar Singh and Fateh Singh – were martyred constitute the basis of the belief among Sikhs in being ready for resistance and martyrdom.

From Bhagat Singh to Moose Wala

The British too found it difficult to handle the Sikhs. In the early 20th century, ICS officer Sir Malcolm Lyall Darling, who spent most of his career as a bureaucrat in Punjab during British Raj, described Punjabis as “hot headed and virile people” and the Sikhs as “having just the qualities that India needs – energy, enterprise, independence: too much independence, perhaps" in his book, ‘At Freedom’s Door’. Anotherunique aspect of the Sikh religious observance is the daily remembrance of Sikh struggles and history in the ardas in the gurdwaras. It is this that drives the community to remember and avenge the incidents of repression and denial of justice, as viewed by the community.

Even the folk songs in Punjabi glorify individuals who stand up to oppression and confront the ruling powers. It was this element that was present in murdered singer Sidhu Moose Wala’s songs and made him beloved of young Punjabis. He has become a hero of the masses along with Bhagat Singh and Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale.

The Punjabi Suba movement raised after Partition by Master Tara Singh, the subsequent carving out of Haryana and Himachal Pradesh from Punjab, and Operation Bluestar and the subsequentanti-Sikhs riots are issues where the Sikh community strongly feels that it was denied justice.

The overshadowing of the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) and Akal Takht by the politics of Shiromani Akali Dal (Badal) led by former chief minister Parkash Singh Badal and his son Sukhbir made the community slowly lose its faith in the institutions that form the bedrock of the Sikh identity and religion.

Disenchantment with religious and political institutions

The irony that SAD was formed just over a century ago to help SGPC is not lost on the community. The stronghold of the Badals on the community has slipped to such an extent that it barely managed to win three seats in the 2022 assembly elections, thoroughly trounced by AAP to third place.

The disenchantment of the youth, especially those from rural and semiurban areas, can be gauged from their overwhelming support for Amritpal Singh and his organisation Waris Punjab De. The motivating factors in his rise are the growing disenchantment with both political and religious organisations.

At the same time, the Punjabi youth, in general, see no future in farming, have no recourse to meaningful employment and dream of migrating to Canada, the UK or Australia, where the community is in sizable numbers and has gained political traction. The failure of the political and religious leadership can push Punjab to where it was over 40 years ago in 1978, understood as the genesis of militancy and rise of Bhindranwale.

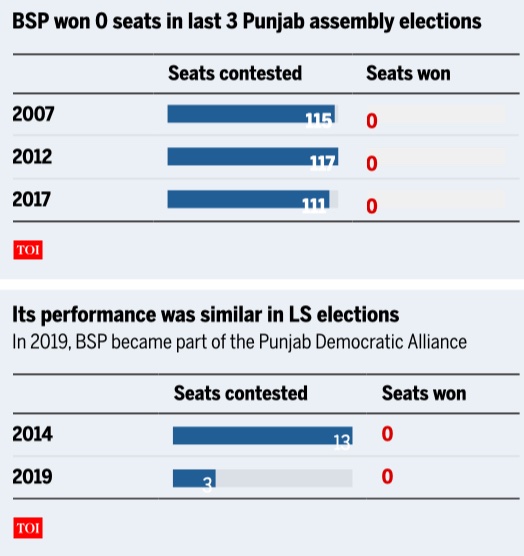

BSP

1992-2019

January 27, 2022: The Times of India

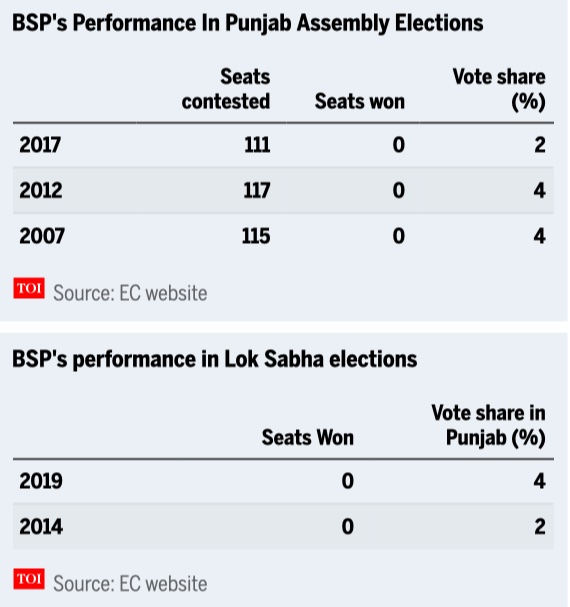

From: January 27, 2022: The Times of India

From: January 27, 2022: The Times of India

The last assembly seat it won in Punjab was 25 years ago.

BSP’s best when it contested on its own

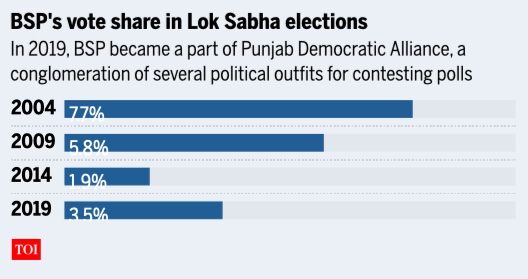

BSP's best performance when it has contested on its own in both state and national polls has been a vote share of 7.67% in the 2004 Lok Sabha elections. This was the year when Mayawati was considered a possibility for the Prime Minister's post in case of a hung Parliament.

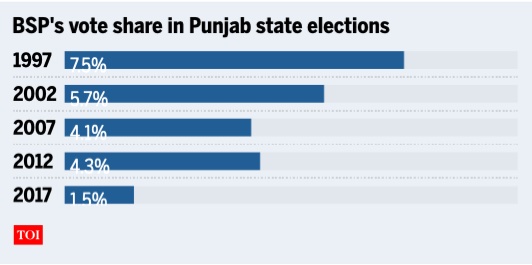

The only time the BSP has managed to get a double-digit vote share of 16.32% and win nine seats, was the unusual state election of 1992 when Akali factions boycotted the polls and total voting turnout in the state was just 23.96%. In the 1997 state election, founder and Dalit icon Kanshi Ram was leading from the front, and BSP managed to get 7.5% of the vote share (it was contesting alone). Even since then, the party’s vote share has consistently been dropping.

In 2002, when the Congress returned to power, the BSP's vote share was 5.69%. In the last state election in 2017, when Congress again emerged the winner, its vote share was reduced to just 1.5% — its worst performance ever — as the entry of the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) dented its base. In fact, only one BSP candidate — then state unit chief Avtar Singh Karimpuri — could save his security deposit at Phillaur from where was contesting.

Why BSP has performed poorly alone

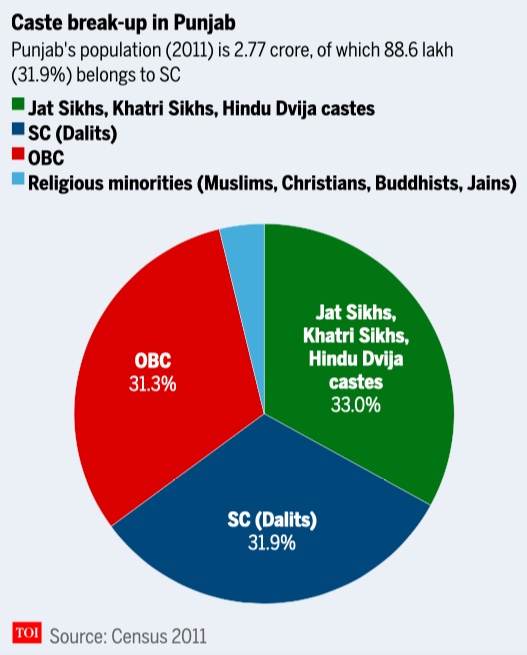

Despite the perception that BSP is a party for scheduled castes (SC), its performance has on the whole been abysmal in Punjab, the state with the highest Dalit population. That’s because SCs are far from being a homogenous identity in the state. SCs make up 31.9%, or about one-third, of the state’s population, predominantly in the Doaba belt.

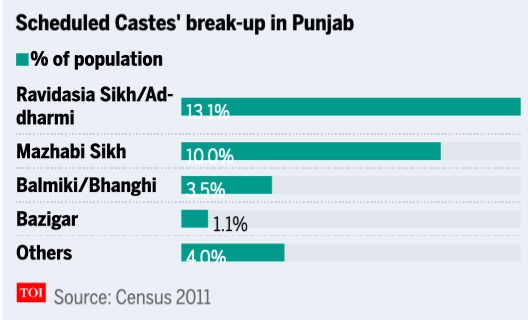

The two biggest communities among SCs in Punjab are the Adh-dharmi/Ravidasia and Valmiki/Mazhabis, and both remain sharply divided, not just socially but also politically. That is the reason why even under Kanshi Ram—even though he was from Punjab and envisioned BSP as a party of bahujans (scheduled castes, scheduled tribes and other backward classes) when he founded it in 1984—BSP has been unable to make an impact in the state's politics.

Among the state's Dalits, the BSP’s main support base belongs mostly to the Ad-dharmi/Ravidasia community. They according to the 2001 Census comprise around 13% share of Punjab’s population. Though this is a large section of the population, this has not translated to votes as the groups within are deeply fragmented. Even Kanshi Ram was unable to bring them on the same page politically. Whatever he did manage, was frittered away over time.

‘But for an alliance’

Which is why BSP cadres and supporters in the state have been pushing for an alliance. In fact, the current tie-up between BSP and SAD is not the first. The BSP tasted electoral success in alliances with Simranjit Singh Mann-led Akali Dal in 1989 Lok Sabha election, and then with the Parkash Singh Badal-led Shiromani Akali Dal in the 1996 parliamentary election when the alliance won 11 out of 13 seats.

However, its alliance with the Congress in the 1998 parliamentary elections failed miserably as the grand old party was quite unpopular at that time.

Ever since then, the party has chosen to contest on its own in Punjab. But that has only made matters worse. Not only has the BSP's vote share kept falling, the party has ended up losing some of its leaders to other parties such as the SAD where the same candidates succeeded. As a result, the party hasn't won a single seat in the last several elections (both state and parliamentary).

Tough battle in 2022

Fast forward to the present election. BSP cadres understand the electoral arithmetic – unable to grow beyond its Ad-dharmi/Ravidasia base, which itself was divided politically – an alliance was crucial. On paper, the SAD-BSP alliance looks to be a winning combination – SAD enjoys influence among the influential Jat Sikh community and BSP has its base among the Dalits.

However, a lot has changed since its successful tie-ups with SAD in 1989 and 1996. Sikhs had then voted in large numbers for the SAD factions led by Mann and Badal, respectively, as they were angry with the Congress. However, this time, the Badal-led Akali Dal is facing its own set of challenges and the party has to recover the base it lost in its core constituency — the Sikhs — during the 2012-17 term. SAD was voted out of power in 2017.

The BSP is also not the same anymore. Till the 2002 assembly elections, the party was anchored by Kanshi Ram, who had charisma and political know-how, and party cadres were fresh and full of energy. But over time, it has found it hard to maintain its base. Kanshi Ram’s successor Mayawati has been able to wield far more influence on UP’s politics than in Punjab where she has struggled to make an impact. Then there is the Congress that has thrown a spanner by appointing Charanjit Singh Channi as the chief minister. Channi comes from the same caste which is the BSP’s core base, and his elevation could affect BSP’s chances. Ironically, when Kanshi Ram launched the BSP, he took out a chunk of Congress’ support and weakened it in UP and Punjab. Now with Channi as the first SC Sikh CM of Punjab, Congress is hoping to get that share back.

Now that it has entered into a pre-poll alliance with SAD, for the BSP there will be little room to take shelter behind the old argument of “but for an alliance”. It's time to perform or perish.

Congress

Pressurising the high command: 2015, 2021

IP Singh, July 20, 2021: The Times of India

JALANDHAR: The factor which worked for Captain Amarinder Singh in 2015 — when he could get support of several MLAs to build pressure on the party high command to get Partap Singh Bajwa replaced as the Punjab PCC president — is now working for Navjot Singh Sidhu.

It is the perception among MLAs and prospective candidates that Sidhu could help them win their seats in the 2022 assembly elections that has made them welcome his appointment as PCC president despite Amarinder’s serious objections and unhappiness.

In 2015, they believed that Amarinder, not Bajwa, could lead them to victory. Amarinder enjoyed such support from party MLAs and other senior leaders that Bajwa was isolated and the high command was forced to replace him.

However, the CM is now facing anti-incumbency and several questions about his government’s work. The same set of MLAs and a few ministers, especially the Majha brigade of three ministers — Tript Rajinder Singh Bajwa, Sukhjinder Singh Randhawa and Sukhbinder Singh Sarkaria — who were in the forefront to organise support for him in 2015, have now sided with Sidhu for the same reason.

Unlike Amarinder, who rallied the MLAs behind himself in 2015 and started holding public functions under ‘Mission Punjab -2017’, Sidhu appeared to be plodding alone. He remained inaccessible to most of the party leaders but stood his ground in questioning the CM through his tweets.

It was Amarinder’s direct attack on Sidhu, challenging him to contest from Patiala, that made the ex-cricketer emerge as the main challenger. This was the beginning of Sidhu’s strengthening his fight within the party.

It was after Jalandhar Cantt MLA Pargat Singh, who too had picked up the gauntlet against the CM, reached out to Sidhu that the latter met a few ministers and MLAs in Chandigarh.

As the party crisis precipitated in Punjab, the Congress high command was forced to intervene, and the balance started tilting. However, most MLAs still did not side with Sidhu even if they did not support Amarinder in their feedback to Congress president Sonia Gandhi.

Sidhu vs Amarinder

2021: the BSP factor

IP Singh, June 23, 2021: The Times of India

From: IP Singh, June 23, 2021: The Times of India

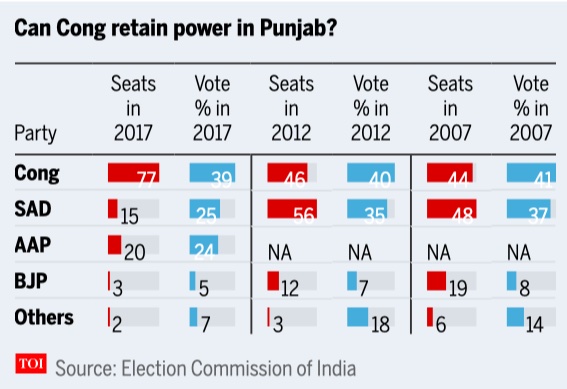

Sidhu – a thorn in chief minister Captain Amarinder Singh’s flesh for a long time now – has already made it clear that his stand will remain unchanged on the issues he has been raising. Of the seven states going to polls in 2022, Congress is in power only in Punjab, where it also has the best chance of returning to power. Or does it?

This question posed a couple of years ago, when the party had looked poised to return to power comfortably, would have been dismissed summarily. But then, it is the Congress – a party that has honed political suicides into a fine art.

With less than a year to go for the election, the party in Punjab is riven with factionalism, is facing anger over mishandling of the probe in the Kotkapura firing case, and must now react to a deftly sewn Shiromani Akali Dal-Bahujan Samaj Party (SAD-BSP) alliance. And then, of course, there is Navjot Singh Sidhu. If politics is about turning adversity into opportunity, the Congress in Punjab has turned the idiom on its head and turned an opportunity it was offered on a platter into an adversity it must now contend with.

The Congress’ prospects had appeared bright not because the state government had done very well and had delivered on its promises in the past four years. It appeared well placed for a return to power because the opposition was fractured with Shiromani Akali Dal and the BJP parting ways and AAP’s fortunes on the decline since 2017. But instead of building on that opportunity, the good prognosis only built complacency in the rank and file, giving space to the opposition to get its act together.

Now with SAD-BSP alliance in place, Congress has its task cut out – to find a response to a partnership that can hurt it in several constituencies. Out of the 23 seats in Doaba region, the BSP has considerable presence in around a dozen. The 2019 Lok Sabha elections already demonstrated that its vote aggregating capacity increases considerably in alliance. The BSP also has the potential to tilt the balance in quite a few other seats in Malwa and Puadh regions.

Meanwhile, Sidhu – a thorn in chief minister Captain Amarinder Singh’s flesh for a long time now – has already made it clear that his stand will remain unchanged on the issues he has been raising. They both seem to be considering it a fight to finish. Sidhu has recently been joined by former Indian hockey captain and member of legislative assembly Pargat Singh has now also been repeatedly questioning the CM on different issues. If it is not an open rebellion, it is not so subtle either. In 2015, Amarinder with the support from a majority of MLAs and party cadre, could force the high command to appoint him as the state party chief and project him as CM candidate in the run-up to the 2017 polls. But this time, not even half of his ministers and MLAs have spoken up for him in public.

What has emboldened Captain’s critics and made his supporters circumspect is the Punjab and Haryana high court order of April 9 scrapping investigation by a special investigation team (SIT) in the Kotkapura firing case. The court also absolved then chief minister Parkash Singh Badal of allegations of conspiracy in the case. Amarinder is facing questions over handling of this emotive case that had helped Congress come to power.

An incident of desecration of the Sikh holy book Guru Granth Sahib at village Bargari in October, 2015 had led to protests across the state. Police firing on protesters at Behbal Kalan village and Kotkapura town in Faridkot district had left two dead and several others injured. This had generated a wave of anger against the SAD-BJP government. The Congress, riding on the promise to deliver justice to the victims and their families, benefited from the discontent. Rahul Gandhi visited the firing victims in 2015 and before the Lok Sabha polls in 2019 held a rally at Bargari.

For a large part of the state’s Sikh electorate, the Congress had become a no-go after Operation Blue Star and the massacre of Sikhs in November 1984. But the police firing incident was a game-changer. As SAD’s popularity touched a new low, Congress regained acceptance it had lost in 1984.

But the same Kotkapura firing incident has now become a liability for the party. Even though a new SIT has restarted the probe, people are disappointed by the delay and party MLAs are facing the heat. In private, Congress MLAs admit there is a perception that Amarinder helped the Badals get off the hook in the Kotkapura, a suggestion that he has strongly denied.

Questions about the state government’s performance on other issues are also being raised. Till 2017 polls, drugs, mining mafia, corruption, lopsided power purchase agreements (PPAs) signed during the SAD-BJP regime to extend the benefit to private players, unemployment were important issues for Congress. But after four years in power, the Congress has not made any progress on these issues. If the Congress loses Punjab in 2022, it will not be a case of a defeat handed by another party, but a self-inflicted blow.

SIDHU VS AMARINDER – THE SLANGING MATCH

Sidhu on Amarinder:

- “I say, ‘you fulfill the agenda; I will support you without a post’. You may even appoint me to the zila parishad. But if you do not fulfill people’s aspirations, no post will matter to me”

- “One man has taken the party for a ride. Who takes decisions as the home minister and then shifts the blame?”

- “Capt Amarinder is not the Congress... he lies every day”

- “A game of chess is being played in Punjab where the king and the 'wazirs' (ministers) are being protected and sepoys are being attacked”

Amarinder on Sidhu:

- “Sidhu doesn’t even know which party he is in. If he is in Congress, then this is total indiscipline. I think maybe he is planning to join AAP or go somewhere else”

- “He is most welcome to contest (from Patiala). Last time, Gen JJ Singh (retd) had come (to contest from Patiala) and forfeited his security deposit. He (Sidhu) will meet the same fate”

- “Why should he be the president?” (On reports that Sidhu was keen to take over as Punjab Congress president or deputy CM)

2019- 2021 Sept: Revolt against the Captain

From: Sep 19, 2021: The Times of India

See graphic:

2019- 2021 Sept: Revolt against the Captain

Caste break up

As in 2011

From: January 27, 2022: The Times of India

See graphic:

Caste break-up in Punjab, 2011

Scheduled castes

From: January 27, 2022: The Times of India

See graphic:

Scheduled Castes' break-up in Punjab, 2011

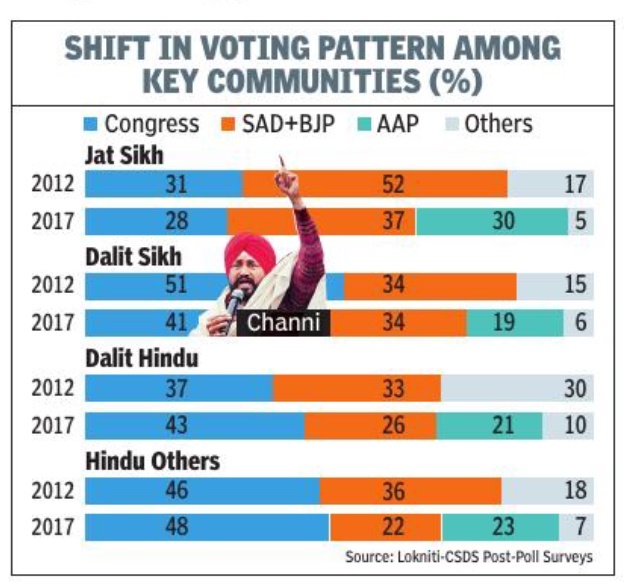

Community- wise voting pattern

2012, 2017

From: February 20, 2022: The Times of India

See graphic:

The Community- wise voting pattern in Punjab, 2012, 2017

Murders of members of religious organisations

2015-17

Payal Dhawan, Top R-S-S official shot; 7th murder in 2 years, Oct 18 2017: The Times of India

The killings began with the murder of Mata Chand Kaur, patriarch of Namdhari Sikhs, on April 4, 2016, and have mostly taken place in Ludhiana and surrounding region.

Of the seven killings, four victims have been members of Hindu right wing organisations. Gosain is the second R-S-S official to be murdered after vice-president of the Punjab unit, brigadier (retd) Jagdish Gagneja was shot in Jalandhar on August 6, 2016.

Despite a clear pattern emerging in the murders, cops have failed to solve any .Senior officers said that they are certain only one group is behind the murders which is trying to foment communal tension in the state with these attacks, but has been unable to get specific leads.

Gosain was the head (mukhya shikshak) of the Mohan Shakha in Amantran colony of Jodhewal area, barely five minutes from his home.

He had returned from the shakha around 7 am and stepped out of his home with his two grandchildren when two men on a motorcycle, who had their faces covered, approached him. They asked Gosain to look at him and then shot him in the head.The moment the R-S-S leader fell to the ground, one of the assailants shot him in the back, killing him on the spot.

Gosain's daughter-in-law Preeti said, “My father-in-law was waiting for my son to put on his school uniform so that he could take him along to get candies. Suddenly , we heard gunshots and rushed out. Papa was dead and both children were screaming.“ Commissioner of police, R N Dhoke, said, “CCTVs installed near the spot have captured two masked assailants on a black and yellow bike. Our men have recovered two bullets shells from the spot, one of a .30 bore revolver and another of a .32 bore revolver indicating two weapons were used.“

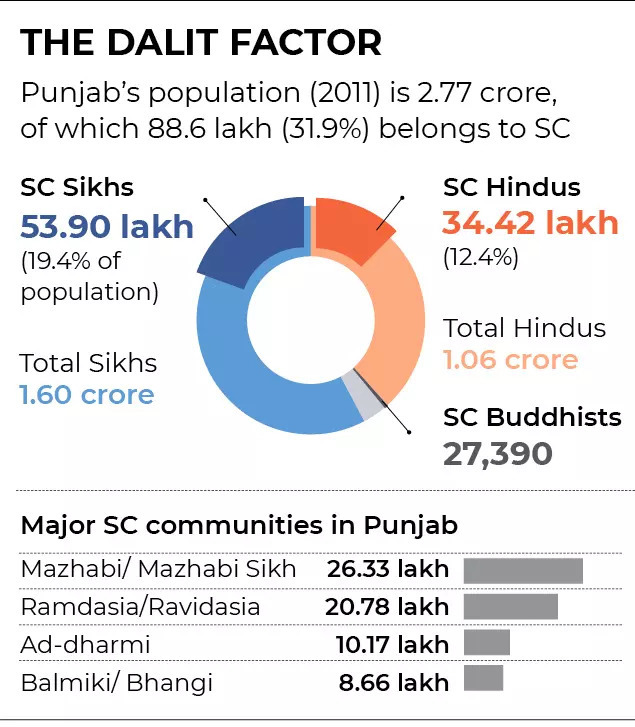

The Scheduled Castes

Influence, as in 2021

IP Singh, February 8, 2022: The Times of India

From: IP Singh, February 8, 2022: The Times of India

AMRITSAR: Scheduled Castes (SC) make up a sizable 31.9% of Punjab's population, which is why their support is crucial to whosoever is forming a government. A significant part of the state's SC population has been a Congress support base and Charanjit Singh Channi’s elevation as the chief minister is expected to further consolidate this base.

However, the impact may not be as linear as is being perceived — strong contradictions, both at the social and political level, have been present within Punjab’s SC community despite common causes uniting them at times.

Numbers versus influence

The two largest SC communities in Punjab are the Ad-dharmis/Ravidasia/Ramdasia Sikhs and Mazhabi Sikhs/Balmikis. The latter constitute roughly 12.6% of Punjab's total population while the former make up about 11%. Amid all the identities, it is the Ad-dharmis that largely drive the SC social and political narrative and wield the maximum influence. This is evident from the influence of Dera Sachkhand Ballan, the power centre of the Ad-dharmi/Ravidasia community. Channi, who belongs to the same community and has repeatedly visited the dera since his elevation, recently announced a Rs 50-crore research centre at Ballan to be managed by a committee headed by the dera head. He even stayed there for a night. A large number of NRIs also make a major support base of the dera, which has only added to its influence in the narrative building. And even though the Mazhabi Sikhs/Balmikis are more in number, they do not have any single institution that can leverage power to such an extent. Prof G C Kaul, former head of Punjabi department at DAV College, Jalandhar, who writes on SC issues and is currently general secretary of Ambedkar Bhawan Trust, Jalandhar, said Ad-dharmis are progressing better in education, as well as socially and economically. “The most influential opinion-makers among the SCs happen to be Buddhists (part of the Ad-dharmis),” he said. Ambedkarite and Buddhist writer Lahori Ram Balley said, “While Balmikis are the most deprived section, even Mazhabi Sikhs are much weaker as compared to Ad-dharmis/Ravidasias in education as well as financially. That is why the latter are dominating socially and politically. There are scores of rich Ad-dharmis/Ravidasia members who are giving further impetus to their community.” About the influence of the Buddhists among them despite low numbers, he said, “Several well-educated and more committed among them followed Babasaheb Ambedkar in defining their religious identity and became Buddhists. They obsessively worked to spread his message and that is why they are more influential in building narratives of all the SCs.”

The political divide

The two communities — Ravidasia/Addharmis and Mazhabi Sikhs/Balmikis — have a history of competing for social and political space and there have been instances in the past when leaders from respective communities have raised fingers at each other. Politically, Ad-dharmis control the BSP. In the Congress and BJP, they are the dominant player among SCs. In the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD), power is equally balanced between the Ramdasia Sikhs and Mazhabi Sikhs, In the last decade though, Ad-dharmis from Punjab's Doaba region have made their presence felt within the SAD.

In recent days, the swing in the Ravidasia/Ad-dharmi community, which comprises SCs who have traditionally been involved in leatherwork, towards Channi is palpable. But reports from the ground reveal that the impact may not be as linear in the Mazhabi Sikhs/Balmikis community. Traditionally, Balmikis, who describe themselves as Hindus in the census and mainly reside in and around urban areas, are Congress supporters, however the Mazhabi Sikhs are divided between Congress and SAD.

Seven decades before Channi History was created when Punjab got its first Sikh SC chief minister in Channi in 2021. Punjab had another noteworthy distinction to its credit 70 years ago. The first leader of opposition, following the first assembly elections post-independence in 1952, was an SC Sikh – Gopal Singh Khalsa. Congress was elected to power and SAD emerged as the main opposition party. Then SAD president, Master Tara Singh, picked Khalsa, an illustrious Ramdasia Sikh, as leader of the opposition.

The social divide

Reservation

Both the communities remain divided on the 12.5% reservation within reservation issue for Mazhabi Sikhs/Balmikis.

In 2006, the Punjab and Haryana high court scrapped a notification issued in 1975 by the Giani Zail Singh-led Congress government to provide this reservation. The Punjab government later passed a legislation to ensure that this reservation gets approval from the state assembly. However, Chamar Mahan Sabha, an NGO fighting for the cause of marginalised communities, opposed this provision and moved the Supreme Court, claiming that reservation within reservation is unconstitutional and should be scrapped.

“The matter is still pending before the Constitutional Bench of the Supreme Court,” Sabha president Paramjit Kainth told TOI, adding that “this reservation within reservation is a ploy of the politicians to create a rift between the two SC groups.”

Major Balmiki organisation Adi Dharam Samaj (ADS) founder and head Darshan Ratan Rawan had a different view. “Our community has been at the lowest step of caste stratification and the most deprived. Our people deserved this reservation but the other community members and leaders have been strongly working against it.”

Marriage

The practice of endogamy, or marrying strictly within the local community, continues even today. For instance, Ravidasias/ Ad-dharmis and Mazhabi Sikhs/Balmikis do not marry among each other, and exceptions are very few. Along with the caste fault line, religious identity also plays its part.

Ad-dharmis, especially those who profess to be Hindu, prefer to marry within the same identity, while Ramdasia Sikhs usually marry within their own community. The same goes for Mazhabi Sikhs and Balmikis, although in political discourse they are often bunched together. In smaller SC communities, the practice is the same.

“It’s extremely rare for Ad-dharmis to marry among Balmikis. They consider themselves a step higher. The only exception is love marriage. I have yet to come across an arranged marriage between Balmikis and Ad-dharmis. Casteism is not just in upper caste people, but is as strong in lower castes,” said ADS founder Rawan. “Different SCs don’t opt for inter-caste marriage among themselves. They also consider caste hierarchy. The larger SC classification has not helped to transcend social barriers completely and they continue to perpetuate,” said Prof G C Kaul.

Caste matters in Punjab

Ad-dharmi

Ad-Dharm was founded in 1920s as a common religious identity for 'untouchable' castes and included in 1931 Census as a religion for different castes. After Independence, it became a caste, for those who worked with leather and were also called Ravidasia. Most of them profess Hindu religion. Ghadarite, politician and Dalit icon Mangu Ram was part of the Ad-dharmi movement.

Ravidasia

The community that worked with leather, this name is also used interchangeably with Ad-dharmis, and people in this community are both Hindus and Sikhs. BSP founder Kanshi Ram was Ravidasia.

Ramdasia Sikhs

Named after Guru Ramdas. Originating from leatherwork community, most switched to weaving after joining the Sikh fold generations ago. The terms ‘Ramdasia Sikh’ and Ravidasia Sikh’ are interchangeable. They also have a regional context. In Puadh and Malwa regions, largely Ramdasia is used while Ravidasia is used in Doaba. CM Charanjit Singh Channi belongs to this group.

Balmikis

The community that used to work in scavenging. They are the most deprived. Most members profess Hinduism. Punjab minister Raj Kumar Verka is from the group.

YEAR-WISE DEVELOPMENTS

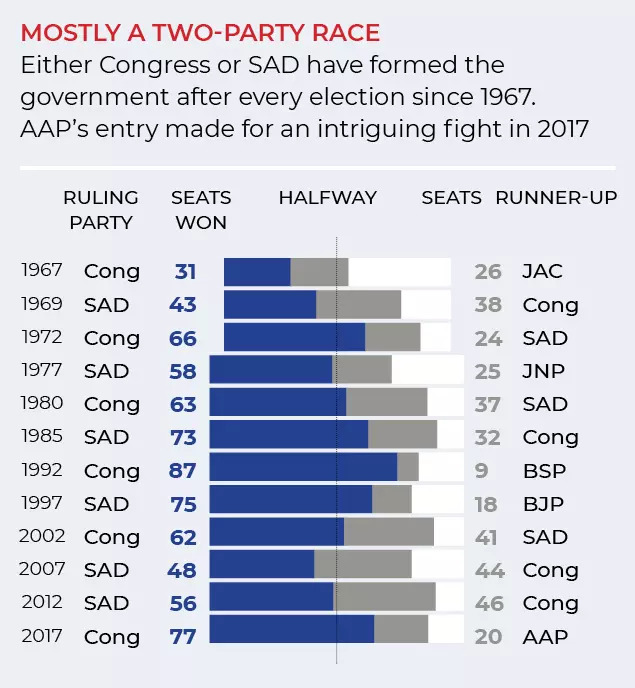

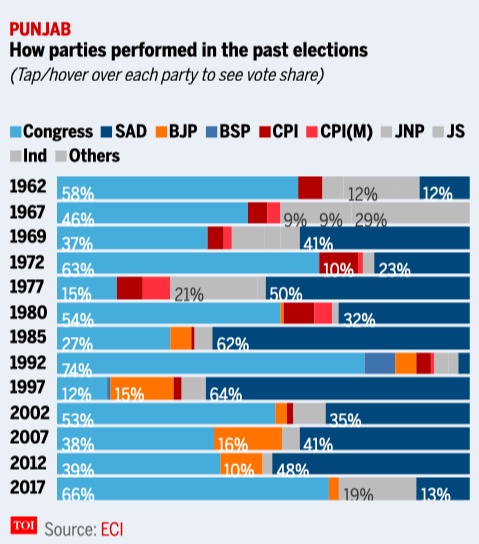

1962, '67-2017: Ruling parties and seats won

From: January 14, 2022: The Times of India

From: January 14, 2022: The Times of India

See graphics:

Ruling parties and seats won in Punjab, 1967- 2017

How parties performed in the past elections, 1962-2017

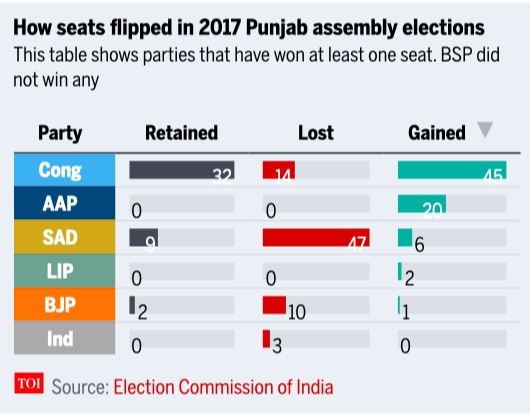

2017: how the seats changed

From: January 27, 2022: The Times of India

From: January 27, 2022: The Times of India

See graphics:

Seats won by BSP in Punjab Assembly elections, 2007-17

This table shows parties that have won only one seat, 2017

2019

CM strips Sidhu of local govt ministry, allots power

Vibhor Mohan, June 7, 2019: The Times of India

Captain strips Sidhu of local govt ministry, allots power

Chandigarh:

Punjab chief minister Capt Amarinder Singh stripped minister Navjot Singh Sidhu of the coveted local government portfolio as well as tourism and cultural affairs ministry on Thursday, less than a month after the cricketerturned-politician had publicly criticised his boss during the Lok Sabha poll campaign. Sidhu has now been allocated power and new & renewable energy resources portfolios.

The reshuffle is set to escalate the war of words between the two. Hours before the changed portfolios were announced, Sidhu skipped the cabinet meeting.

Performer like me cannot be taken for granted: Sidhu

I cannot be taken for granted. I say that with humility. I’ve been a performer throughout — be it cricket, commentary, television or as a motivational speaker,” Sidhu said.

Countering Amarinder’s criticism that it was Sidhu’s “failure to do development work” that had cost Congress the urban vote bank in places like Bathinda and Sangrur, the former cricketer released details to point out that cities and towns, in fact, had played a pivotal role in the party’s victory in Punjab. He said that while in urban areas, Congress’s strike rate was 63%, in the rural areas it was 55%.

Amarinder has given the local government portfolio to Brahm Mohindra. Sidhu’s portfolio of tourism and cultural affairs has gone to Charanjit Singh Channi. After the election results, Amarinder had indicated that he intended to change Sidhu’s department. Amarinder said the rejig would help streamline the government systems and bring more transparency and efficacy into various departments. The CM said he hoped that the changes would re-energise his team and bring freshness to the working of the major departments.

2024

Lok Sabha elections

June 5, 2024: The Times of India

From: June 5, 2024: The Times of India

Chandigarh: The intense multi-cornered contest in 13 parliamentary constituencies in Punjab amid sweltering heat culminated in Congress winning seven constituencies, ruling Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) three, Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) one. Two independent candidates, including jailed pro-Khalistan Sikh preacher Amritpal Singh from Khadoor Sahib, also won.

Former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s assassin Beant Singh’s son Sarabjit Singh Khalsa, is the second independent candidate who clinched the Faridkot (reserved) constituency on his main poll plank of seeking justice for the October 2015 Guru Granth Sahib desecration case at Bargari. The results of Khadoor Sahib, Faridkot and Sangrur constituencies highlights simmering discontent among Sikhs against traditional political parties.

Amritpal Singh, who contested as an independent, won the Khadoor Sahib seat by the highest margin in Punjab — over 1.97 lakh votes. Former chief minister and Congress candidate Charanjit Singh Channi won the Jalandhar (reserve) by over 1.75 lakh votes. However, Congress’s Sher Singh Ghubaya just managed to scrape through, beating AAP’s Jagdeep Singh Kaka Brar, by the lowest margin of 3,242 votes.

The SAD and the BJP contested this election without alliance for the first time since 1996. Though the BJP failed to retain its two existing seats of Gurdaspur and Hoshiarpur, it succeeded in increasing its vote share to 18.56% against SAD’s 13.42%, which points to BJP’s consolidation of Hindu votes.

Out of seven sitting MPs who were renominated by their parties, only three—SAD’s Harsimrat, Congress’s Dr Amar Singh (Fateh- garh Sahib), and Congress’s Gurjit Singh Aujla (Amritsar) —could save their seats. Congress’s sitting MP from Anandpur Sahib, Manish Tewari, who was contesting from Chandigarh this time, was successful, but with a very slim margin.

A total of 12 MLAs, including five cabinet ministers of the AAP government, were in fray in the June 1 Lok Sabha elections. Of these, only one cabinet minister and Barnala MLA Gurmeet Singh Meet Hayer could win his Sangrur constituency. Other than Meet Hayer, only two MLAs were successful—Congress’s Dera Baba Nanak legislator Sukhjinder Singh Randhawa (Gurdaspur) and Dr Raj Kumar Chabbewal, who was elected to assembly on Congress ticket and now has won the Lok Sabha seat on AAP ticket.

Also, Vidhan Sabha speaker accepted the resignation of AAP’s Jalandhar West MLA Sheetal Angura.

A

IP Singh, June 5, 2024: The Times of India

Jalandhar: The results from Khadoor Sahib and Faridkot Lok Sabha seats in Punjab indicate a big churn inside the Sikh political space along with the re-emergence of Panthic politics. Radical preacher Amritpal Singh has won from Khadoor Sahib and Sarabjit Singh — the son of Indira Gandhi’s assassin Beant Singh — from Faridkot, both as Independents.

Amritpal was arrested last year, charged under the National Security Act and kept in jail in Assam’s Dibrugarh.

Coming in the 40th anniversary week of 1984’s Operation Bluestar at the Golden Temple that had led to Indira’s assassination that Oct and a Sikh massacre in Delhi in Nov, Sarabjit’s victory has proved that the Sikhs have found no closure.

Simranjit Singh Mann lost from Sangrur, a seat that he had won in a 2022 byelection just three months after AAP’s landslide in the state. Yet he has passed his baton of radical politics to a younger lot. Sangrur, vacated earlier by CM Bhagwant Mann, was the most prestigious seat for AAP. Faridkot threw up a bigger surprise when Sarabjit defeated comic actor Karamjit Anmol despite having little network. His campaign picked up just a few days before the polls, while Anmol had CM Bhagwant and major entertainers canvassing for him for weeks.

Like the turmoil of the 1980s and 1990s had worked for the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD), Sikh issues of justice worked for AAP. There were also some issues of governance.