Pushkar fair

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

History

Shoeb Khan, Nov 6, 2022: The Times of India

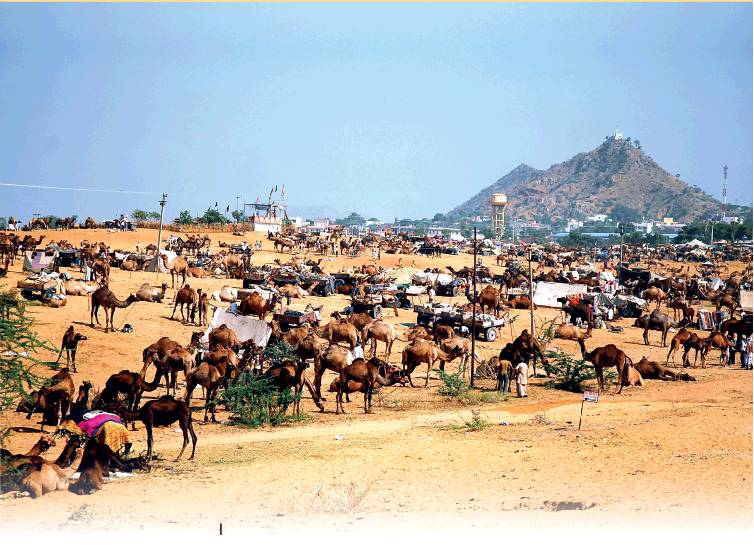

FAIR USED TO BE A SEA OF CAMELS

➤The official claim that the camel market was historically not part of the Pushkar Fair seems doubtful. The Rajputana Gazetteer of 1879 says : “In 1877, there were about 401 horses, 1,495 camels and 1,985 bullocks” at the fair

➤Murray’s ‘Handbook to India, Ceylon, Burma and Cashmere’, published in 1894, says: “Early in the Middle Ages it (Pushkar) became one of the most frequented objects of pilgrimage, and is still visited during the great Mela of Oct and Nov by about 100,000 pilgrims. On this occasion is also held a great mart for horses, camels and bullocks” ➤Bhima Ram from the Raika community of camel herders has seenthe glory days of camel trade in his youth. He started coming to the fair when he was 10. There were camels as far as the eye could see, he told TOI. “I have seen 40,000-50,000 camels in the fair for years in the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s”

➤As late as 1999, the book ‘100 Things To Do Before You Die’ noted: “You’ll find the Camel Fair situated in the desert just to the west of town. The focus is on buying and selling camels; about 30,000 of the snarling beasts trade hands during the week”

➤But those days are a fading memory now. In 2019 there were just 2,500-3,000 camels, said Bhima Ram. And this year saw only 800-1000

Changes over the years

As in 2018

From: Naomi Canton, Much has changed in Pushkar, except the marriage proposals, November 5, 2018: The Times of India

The camel fair is nearly gone and with it the hustle and bustle in the bazar. Unlike the 90s, shopkeepers this time were busy with their mobiles and barely noticed tourists

When I first went to Pushkar in the 1990s, the shopkeepers used to call out: “Hello madam, which country? You want marriage? Come inside. No charge.” I returned a few years ago and nothing had changed. Each night I would wander through a colourful sea of shops selling camel models, handcrafted silver rings, mirrored wall hangings. The shopkeepers still yelled: “Come inside! Just looking”, and offered me chai.

But this time, my 10-day trip to Pushkar which I have just returned from, was different. I walked through the bazaar but no one spoke to me because they were all staring at their phones. The shops often lay empty but the shopkeepers didn’t seem to care as they browsed the internet. I had quite enjoyed the noise earlier – walking through the streets and saying “England” and “namaste” to different shopkeepers.

However, this time, even if I went into a shop, the shopkeeper barely noticed my presence and just sat glued to his mobile. Chai was rarely offered and I bought without much bargaining.

Some hotel and restaurant owners told me business was down and fewer European visitors came, but this was partly offset by an increase in Israelis and Indian tourists. “The Israelis don’t like us harassing them, so we have stopped,” one of them said. Though there was little engagement with me when I wanted it, there was plenty when I did not – mostly at Pushkar lake.

As soon as I sat down, a man arrived and serenaded me with an ektara. Then a gora in a red Aladdin-style costume danced, and another one with long dreadlocks juggled in front of the lake next to the cows. While this was going on, someone arrived to repair my shoes. Then a woman came to paint my hands in henna. A fifth person offered to show me the “Brahma temple”, quietly promising some charas on the side.

On another occasion a local man on a motorbike told me he would show me the “best thing in Pushkar.” Excited to see one of the 500-plus temples I had been told about, I jumped on. He roared through the bazaar, informing me that he was taking me to the only place in Pushkar that served beer. I found this odd as alcohol is banned in the town. I went inside to see locals chugging mugs of the beverage.

Pushkar is a small town and the news headlines of Mumbai and Delhi have little resonance there. Issues like the Pushkar camel fair, how “it is getting ruined”, encroachment of the desert were what people seemed to care about. I met Ashok Tak, camel decorator and tourism promoter, who said that 10,000 camels came to the camel fair in 2015.

But in 2017, there were 2,500. “People are not interested in keeping camels anymore because the government doesn’t provide the support,” he said.

He may have a point. In 2014-15, 9,934 camels were brought to the fair and 3,349 were sold. In 2017-18, only 827 were sold.

Despite that, the number of camel safaris and agents has only increased. The first half of my camel trek was along roads, battling cars and motorbikes. It did not feel much like a safari. It was a while before I could see patches of some sand.

“It used to be a sand dune 12 years ago,” Tak said. “But the state government decided to build a road in the heart of the desert.” Sand mining is banned in the state. “There used to be nice big dunes. Most of the dunes have been stolen. There are just a few left now. People steal the sand to fill up the foundation of their houses. Some hotels in Pushkar are creating artificial dunes,” Tak added.

Though many aspects of Pushkar have changed, one thing has not: marriage proposals. The language of courtship may be different now, but the offers keep coming. One night I walked into an empty restaurant and the waiter asked for my number. Another night, I happened to chat with a hotel manager. Within an hour he had proposed.