Rāzu/ Raju

This article is an excerpt from Government Press, Madras |

Rāzu

The Rāzus, or Rājus, are stated, in the Madras Census Report, 1901, to be “perhaps descendants of the military section of the Kāpu, Kamma, and Velama castes. At their weddings they worship a sword, which is a ceremony which usually denotes a soldier caste. They say they are Kshatriyas, and at marriages use a string made of cotton and wool, the combination peculiar to Kshatriyas, to tie the wrist of the happy couple. But they eat fowls, which a strict Kshatriya would not do, and their claims are not universally admitted by other Hindus. They have three endogamous sub-divisions, viz., Murikināti, Nandimandalam, and Sūryavamsam, of which the first two are territorial.” According to another version, the sub-divisions are Sūrya (sun), Chandra (moon), and Nandimandalam. In a note on the Rāzus of the Godāvari district, the Rev. J. Cain sub-divides them into Sūryavamsapu, Chandravamsapu, Velivēy abadina, or descendants of excommunicated Sūryavamsapu and Rāzulu. It may be noted that some Konda Doras call themselves Rāja (= Rāzu) Kāpus or Reddis, and Sūryavamsam (of the solar race). “In the Godāvari delta,” Mr. Cain writes, “there are several families called Basava Rāzulu, in consequence, it is said, of their ancestors having accidentally killed a basava or sacred bull. As a penalty for this crime, before a marriage takes place in these families, they are bound to select a young bull and young cow, and cause these two to be duly married first, and then they are at liberty to proceed with their own ceremony.”

Of the Rāzus, Mr. H. A. Stuart writes that “this is a Telugu caste, though represented by small bodies in some of the Tamil districts. They are most numerous in Cuddapah and North Arcot, to which districts they came with the Vijayanagar armies. It is evident that Rāzu has been returned by a number of individuals who, in reality, belong to other castes, but claim to be Kshatriyas. The true Rāzus also make this claim, but it is, of course, baseless, unless Kshatriya is taken to mean the military class without any reference to Aryan origin. In religion they are mostly Vaishnavites, and their priests are Brāhmans. They wear the sacred thread, and in most respects copy the marriage and other customs of the Brāhmans.” The Rāzus, Mr. Stuart writes further, are “the most numerous class of those who claim to be Kshatriyas in North Arcot. They are found almost entirely in the Karvetnagar estate, the zemindar being the head of the caste. As a class they are the handsomest and best developed men in the country, and differ so much in feature and build from other Hindus that they may usually be distinguished at a glance.

They seem to have entirely abandoned the military inclinations of their ancestors, never enlist in the native army, and almost wholly occupy themselves in agriculture. Their vernacular is Telugu, since they are immigrants from the Northern Circars, from whence most of them followed the ancestors of the Karvetnagar zamindar within the last two centuries. In religion they are mostly Vaishnavites, though a few follow Siva, and the worship of village deities forms a part of the belief of all. Their peculiar goddess is called Nimishāmba who would seem to represent Parvati. She is so called because in an instant (nimisham) she once appeared at the prayer of certain rishis, and destroyed some rākshasas or giants who were persecuting them. Claiming to be Kshatriyas, the Rāzus of course assume the sacred thread, and are very proud and particular in their conduct, though flesh-eating is allowed. In all the more well-to-do families the females are kept in strict seclusion.” In the Vizagapatam district Rāzus are recognised as belonging to two classes, called Konda (hill) and Bhū (plains) Rāzu. The former are further divided into the following sections, to which various zamindars belong:—Konda, Kōdu, Gaita, Mūka, Yēnāti. The Konda Rāzus are believed to be hill chiefs, who have, in comparatively recent times, adopted the title of Rāzu.

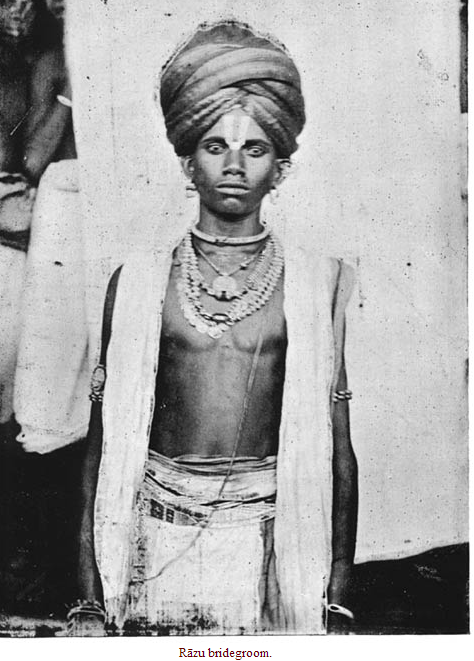

For the following note on the Rāzus of the Godāvari district, I am indebted to Mr. F. R. Hemingway. “They say they are Kshatriyas, wear the sacred thread, have Brāhmanical gōtras, decline to eat with other non-Brāhmans, and are divided into the three classes, Sūrya sun), Chandra (moon), and Machi (fish). Of these, the first claim to be descended from the kings of Oudh, and to be of the same lineage as Rāma; the second, from the kings of Hastināpura, of the same line as the Pāndavas; and the third, from Hanumān (the monkey god) and a mermaid. Their women observe a very strict rule of gōsha, and this is said to be carried so far that a man may not see his younger brother’s wife, even if she is living in the same house, without violating the gōsha rule. The betrothal ceremony is called nirnaya bhōjanam, or meal of settlement. Written contracts of marriage (subha rēka) are exchanged. The wedding is performed at the bride’s house. At the pradānam ceremony, no bonthu (turmeric thread) is tied round the bride’s neck. The bridegroom has to wear a sword throughout the marriage ceremonies, and he is paraded round the village with it before they begin. The gōsha rule prevents his womenfolk from attending the marriage, and the bride has to wear a veil. The ceremonies, unlike those of other castes, are attended with burnt offerings of rice, etc. Among other castes, the turmeric-dyed thread (kankanam), which is tied round the wrists of the contracting couple, is of cotton; among the Rāzus it is of wool and cotton. The Rāzus are chiefly employed in cultivation. Some of them are said to attain no small proficiency in Telugu and Sanskrit scholarship. Zamindars of this caste regard Kāli as their patron deity. The Rāzus of Amalāpuram specially adore Lakshmi. Some peculiarities in their personal appearance may be noted. Their turbans are made to bunch out at the left side above the ear, and one end hangs down behind. They do not shave any part of their heads, and allow long locks to hang down in front of the ears.”

A colony of Rāzus is settled at, and around Rājāpālaiyam in the Tinnevelly district. They are said to have migrated thither four or five centuries ago with a younger brother of the King of Vizianagram, who belonged to the Pūsapāti exogamous sept. To members of this and the Gottimukkula sept special respect is paid on ceremonial occasions. The descendants of the original emigrants are said to have served under southern chieftains, especially Tirumala Naick. Concerning the origin of the village Rājāpālaiyam the following legend is narrated. One Chinna Rāju, a lineal descendant of the Kings of Vizianagram, settled there with others of his caste, and went out hunting with a pack of hounds. When they reached the neighbouring hill Sanjīviparvatham, they felt thirsty, but could find no water. They accordingly prayed to Krishna, who at once created a spring on the top of the hill. After quenching their thirst thereat, they proceeded westward to the valley, and the god informed them that there was water there, with which they might again quench their thirst, and that their dogs would there be attacked by hares. At this spot, which they were to consider sacred ground, they were to settle down. The present tank to the westward of Rājāpālaiyam, and the chāvadi (caste meeting-place) belonging to the Pūsapātis are said to indicate the spot where they originally settled. The Rājāpālaiyam Rāzus have four gōtras, named after Rishis, i.e., Dhananjayā, Kasyapa, Kaundinya and Vasishta, which are each sub-divided into a number of exogamous septs, named after villages, etc. They are all Vadagalai or Tengalai Vaishnavites, but also worship Ayanar, and send kāvadi (portable canopy) to Palni in performance of vows. Their family priests are Brāhmans.

The betrothal ceremony of the Rāzus of Rājāpālaiyam is generally carried out at the house of the girl. On a raised platform within a pandal (booth), seven plates filled with plantain fruits, betel, turmeric, cocoanuts, and flowers are placed. A plate containing twenty-five rupees, and a rāvike (female cloth), is carried by a Brāhman woman, and set in front of the girl. All the articles are then placed in her lap, and the ceremony is consequently called odi or madi ninchadam (lap-filling).

The girl’s hair is decked with flowers, and she is smeared with sandal and turmeric. A certain quantity of paddy (unhusked rice) and beans of Phaseolus Mungo are given to the Brāhman woman, a portion of which is set apart as sacred, some of the paddy being added to that which is stored in the granary. The remainder of the paddy is husked in a corner of the pandal, and the beans are ground in a mill. On the marriage morning, the bride’s party, accompanied by musicians, carry to the house of the bridegroom a number of baskets containing cocoanuts, plantains, betel, and a turban. The bridegroom goes with a purōhit (priest), and men and women of his caste, to a well, close to which are placed some milk and the nose-screw of a woman closely related to him. All the women sprinkle some of the milk over his head, and some of them draw water from the well. The bridegroom bathes, and dresses up.

Just before their departure from the well, rice which has been dipped therein is distributed among the women. At the bridegroom’s house the milk-post, usually made from a branch of the vekkali (Anogeissus latifolia) tree, is tied to a pillar supporting the roof of the marriage dais. To the top of the milk-post a cross-bar is fixed, to one arm of which a cloth bundle containing a cocoanut, betel and turmeric, is tied. The post is surmounted by leafy mango twigs. Just before the milk-post is set up, cocoanuts are offered to it, and a pearl and piece of coral are placed in a hole scooped out at its lower end. The bundle becomes the perquisite of the carpenter who has made the post. Only Brāhmans, Rāzus and the barber musicians are allowed to sit on the dais. After the distribution of betel, the bridegroom and his party proceed to the house of the bride, where, in like manner, the milk-post is set up.

They then return to his house, and the bridegroom has his face and head shaved, and nails pared by a barber, who receives as his fee two annas and the clothes which the bridegroom is wearing. After a bath, the bridegroom is conducted to the chāvadi, where a gaudy turban is put on his head, and he is decorated with jewels and garlands. In the course of the morning, the purōhit, holding the right little finger of the bridegroom, conducts him to the dais, close to which rice, rice stained yellow, rice husk, jaggery (crude sugar), wheat bran, and cotton seed are placed. The Brāhmanical rites of punyāhavāachanam (purification), jātakarma (birth ceremony), nāmakaranam (name ceremony), chaulam (tonsure), and upanayanam (thread ceremony) are performed. But, instead of Vēdic chants, the purōhit recites slōkas specially prepared for non-Brāhman castes. At the conclusion of these rites, the bridegroom goes into the house, and eats a small portion of sweet cakes and other articles, of which the remainder is finished off by boys and girls. This ceremony is called pūbanthī. The Kāsiyātra (mock flight to Benares) or Snāthakavritham is then performed.

Towards evening the bridegroom, seated in a palanquin, goes to the bride’s house, taking with him a tray containing an expensive woman’s cloth, the tāli tied to gold thread, and a pair of gold bracelets. When they reach the house, the women who have accompanied the bridegroom throw paddy over those who have collected at the entrance thereto, by whom the compliment is returned. The bridegroom takes his seat on the dais, and the bride is conducted thither by her brothers. A wide-meshed green curtain is thrown over her shoulders, and her hands are pressed over her eyes, and held there by one of her brothers, so that she cannot see. Generally two brothers sit by her side, and, when one is tired, the other relieves him. The purōhit invests the bridegroom with a second thread as a sign of marriage. Damp rice is scattered from a basket all round the contracting couple, and the tāli, after it has been blessed by Brāhmans, is tied round the neck of the bride by the bridegroom and her brothers. At the moment when the tāli is tied, the bride’s hands are removed from her face, and she is permitted to see her husband. The pair then go round the dais, and the bride places her right foot thrice on a grindstone.

Their little fingers are linked, and their cloths tied together. Thus united, they are conducted to a room, in which fifty pots, painted white and with various designs on them, are arranged in rows. In front of them, two pots, filled with water, are placed, and, in front of the two pots, seven lamps. Round the necks of these pots, bits of turmeric are tied. They are called avareti kundalu or avireni kundalu, and are made to represent minor deities. The pots are worshipped by the bridal couple, and betel is distributed among the Brāhmans and Rāzus, of whom members of the Pūsapāti and Gottimukkala septs take precedence over the others. On the following day, the purōhit teaches the sandyavandhanam (morning and evening ablutions), which is, however, quite different from the Brāhmanical rite. the morning of the third or nāgavali day, a quantity of castor-oil seed is sent by the bride’s people to the bridegroom’s house, and returned. The bride and bridegroom go, in a closed and open palanquin, respectively, to the house of the former. They take their seats on the dais, and the bride is once more blindfolded. In front of them, five pots filled with water are arranged in the form of a quincunx. Lighted lamps are placed by the side of each of the corner pots.

On the lids of the pots five cocoanuts, plantains, pieces of turmeric, and betel are arranged, and yellow thread is wound seven times round the corner pots. The pots are then worshipped, and the bridegroom places on the neck of the bride a black bead necklace, which is tied by the Brāhman woman. In front of the bridegroom some salt, and in front of the bride some paddy is heaped up. An altercation arises between the bridegroom and the brother of the bride as to the relative values of the two heaps, and it is finally decided that they are of equal value. The bridal pair then enter the room, in which the avireni pots are kept, and throw their rings into one of the pots which is full of water. The bridegroom has to pick out therefrom, at three dips, his own ring, and his brother-in-law that of the bride. The purōhit sprinkles water over the heads of the pair, and their wrist-threads (kankanam) are removed. They then sit in a swing on the pandal for a short time, and the ceremonies conclude with the customary waving of coloured water (ārati) and distribution of betel. During the marriage ceremony, Rāzu women are not allowed to sit in the pandal. The wives of the more well-to-do members of the community remain gōsha within their houses, and, strictly speaking, a woman should not see her husband during the daytime. Many of the women, however, go freely about the town during the day, and go to the wells to fetch water for domestic purposes.

The Rāzus of Rājāpālaiyam have Rāzu as the agnomen, and, like other Telugu classes, take the gōtra for the first name, e.g., Yaraguntala Mudduswāmi Rāzu, Gottimukkala Krishna Rāzu. The women adhere with tenacity to the old forms of Telugu jewelry. The Rāzus, in some villages, seem to object to the construction of a pial in front of their houses. The pial, or raised platform, is the lounging place by day, where visitors are received. The Rāzus, as has been already stated, claim to be Kshatriyas, so other castes should not sit in their presence. If pials were constructed, such people might sit thereon, and so commit a breach of etiquette. In the Madras Census Report, 1901, Rājāmakan is given as a Tamil synonym for Rāzu, and Rāzu is returned as a title of the Bagata fishermen of Vizagapatam. Rāzu is, further, a general name of the Bhatrāzus.