Rajput, Kshatriya, Chhatri, Chhettri

Contents |

Rajput, Kshatriya, Chhatri, Chhettri

This section has been extracted from THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all posts in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

Origin

The fighting and land¬holding caste of Northern India, who claim to be the modern representative of the Ksha-triyas of classical tradition, and who are in many cases entitled to appeal to their markedly Aryan cast of feature in support of their claim. Besides these Aryan Rajputs, the large group designated indifferently by the name Rajput or Chhatri includes many families of doubtful or non-Aryan descent, whose pretensions to membership of the twice-born warrior caste rest solely upon the circumstances that they have, or are supposed to have, some sort of proprietary dominion over land. It would be out of place to attempt to give here an exhaustive account of the Rajput community as it exists in Raj-putana and North-Western India. The peculiar characteristics of the pure-blooded Hajput have been described by several competent obser¬vers. Among the most conspicuous are a pride of blood, which delights in endless genealogies and ranks everyone according to descent; a strong passion for Beld sports, combined with an equally pronounced distaste for peaceful and prosaio means of earning a livelihood; and an exaggerated idea of the saving virtues of cere-monial purity and precision in the matter of food and drink.

The same characteristics are doubtless to some extent trace¬able among the Rajputs of the Lower Provinces; but the pressure of different conditions of life has tended to obliterate many distinctions, and the eastern Rajput is far less peculiar than the Western. It is commonly said that the Rajput can only be studied in his original surroundings, and that an account of the tribe as it exists in Bengal must necessarily be valueless and- misleading. There is much truth in this view: at the same time it may be observed that outlying branches of a tribe which have wandered far away from the original habitat often preserve survivals of usages 'which have died out among the original stock or have been overlaid and obscured so as to be no longer traceable. Again, if there is reason to believe, as several good observers think there is, that the IHjput tribe itself has been recruited now and again by irregular methods from men of alien lineage, may there not be a better chance of observing the working of this proctlss in distant districts than in Rajputana itself, where all departures from the strict theory of descent are speedily condoned and hidden by the operation of fiction.

In Chota Nagpur, for example, the methods by which many of the chief landholding families have transformed themselves into Hajputs may be traced beyond question at the present day. The Maharajas of Chutia Nagpur Proper, that is of the elevated table land forming the southern portion of the Lohardaga district, call themselves Nagbansi, and ?claim descent mysterious child. found in the jungle concernmg whose ongm a smgular story IS told. The myth of the birth of the founder of the. Chutia Nagpur house from a Brahman mother and a snake father, with the picturesque incidents which Colonel Dalton relates, seems to be nothing more than an ingenious invention contrived to mask the fact that a family of Munda chieftains had assumed the rank of Hajput. To this day ladies of Nagbansi families will not employ a Munda to carry their palkis, becau e they say he is their elder brother-in-law (blzaistt1"), and they veil their faces before him. as they would before an elder brother-in-law. The Pachete family call themselves Gobansi Rajputs and tell a strange story, analogous to the Nagbansi myth, of the birth of their progenitor from. a cow in the jungle near Pachete. The zamindars of Barabhum, Patkum, Nawagarh and Katiar in Manbhnm all claim to be Hajputs, and boldly affiliate themselves to the Haksel and Chandel clans. Some minor landholders of the Bhumij tribe who hold ghatwali tenures in Barabhum have followed the example of the zamindar of that estate, and call themselves Raj puts, though in. some cases. it can be shown by documentary evidence that then ancestors 10 the last generation called themselves Bhumij.

Traditions

The traditions of the tribe go back to the dateless antiquity in which so many royal pedigrees seek refuge. Accordnig .to the usually . accepted version there are two branches of HaJputs-the Sura] bansi or Solar Race and the Chaudrabansi or Lunar Race. To thes must be added the four Agnikulas or Fire Tribes. Surajbansi Rajputs claim descent from Tkshwaku, son of the Manu Vaivaswat, who was tbe son of Vivaswat, the Sun. Ikshwaku, it is said, was born from the nostril of the Manu as he happened to sneeze. The elder branch of the Solar race sprang from lkshwaku's eldest son Vikukshi, and reigned in Ayodhya. at the bpginning of the second or Treta. Yuga. Another son named Nimi founded the dynasty of Mithila. The Lunar race affect to be descended from the moon, to whom they trace through Ayus, Pururavas and Budha or Mercury, the son of Soma by Hohini or by Tara., wife of Brihaspati. The Agnikulas or Fire Tribes are supposed to have been brought into existence by a special act of creation of compara¬tively recent mythological date.

After the Kshatriya had been slain by Parllsu Hama, gods and men, and more particularly the Brahman began to feel the consequences of the loss of their natural protectors: The earth was ovelTun by ~iaDts and demons (Daityas and Asttras), tbe sacred books were held 10 contempt, and there was none to whom the devout could call for help in their troubles. Viswamitra, once a Kshatriya, who had raised himself to be a Brahman by the might of

penance determined to revive the race that had been exterminated, and moved the gods to assemble for this purpose on Mount Abu in Rajputana. Four images of Dhttba grass were thrown into the fire fountain, and called into life by appropriate incantations. From these sprung the four fire• tribes, PramaI', Sulanki, Parihar and Chauhan.

Turning from mythology to fact, the first point to be noticed about the Rajput tribe is that, in theory at any rate, it has no endogamous subdi visions. All Rajputs are supposed to be of one blood, and no distinctions are formally recognized among them as forming a conclusive bar to intermarriage. The groupings Surajbansi, Sombansi and Agn i kula refer only to traditions of origin, and there is nothing to prevent a man belonging to one of these divisions from marrying a woman who belongs to another subdivision. It is no doubt the case that some exogamous divisions are of higher rank than others, and that to give a daughter in maniage into one of these groups degrades her family in respect of future marriages for a period of seven years. But with a few doubtful exceptions in outlying districts the principle of hypergamy has not been pushed to the point of forming strictly endogamous groups.

Internal structure

The original septs of the Rajput tribe appear to be for Internal structure. the most part of the territorial type, that is to say, their names seem to denote the tract of country in which the sept or its founder had their earliest habitat. Sesodia and Bhadauria may be taken as examples of this type. Other names again, such as .Jadubansi, clearly refer to descent from particular families or stocks. In addition to their original septs, long lists of which are given in Appendix I, the lUjputs of Behar also recognize the Brahm::Lllical yotl'as, and the tendency is for the latter series to supplant and take the place of the latter. Usually where the original sept names are still held to govern intermarriage, the rule is that a man may not marry a woman who belongs to the same sept as his fa.ther or his mother, and the prohibition is often extended to the septs, of the paternal and maternal grandmothers. Notwithstanding this rule a case has been brought to my notice in which the son ot a Salanki Rajput of Behar married a woman of the Chandel sept, although his father bad married into the same sept. At the time of the betrothal a question was raised as to the correctness of the procedure, and the Brahmans held that, as the son's betrothai, though of the same tl'ibaZ sept as his mother, belonged to a different Brahmanical gotm, the l'ule of exogamy would not be infringed by the marriage. The standard formula for reckoning prohibited degrees is also recognized by the Behar Rajputs, who in theory considered it binding down to seven generations on the father's, and five on the mother's side. A man may marry two sisters, but he must take them in the order of age, and he cannot marry the elder sister if he is already married to the younger.

Isogamy and hypergany

In theory, as has been already stated, the whole body of Rajputs constitutes a single tribe divided into a very large number of septs or clans of descent, gamy. each of which is supposed to be descended from a common ancestor. Marriage within the sept is of course interdicted to its member, and in theory a Rajput belonging to any given sept has the whole community to choose from in seeking a bride for his son or a bridegroom for his daughter. In fact, however, the field of selection is greatly restrioted by the operation of the laws of isogamy and hypergamy, the nature of whioh has been explained in the Introductory Essay. In a society so organized as to give the fullest play to the idea of purity of desoent and the tradition of oeremonial orthodoxy, it must needs be that offenoes should oome, and should be deemed to affeot not only the offender himsel£ and his family in the narrower sense, but the entire sept to whioh he belongs, which is oonceived as an enlarged family. 'l'hus in oourse of time is developed an infinite series of sooial distinotions giving rise to oomplioated and burdensome obligations in respeot of marriage.

In the oase of the Rajputs these distinctions have not led to the formation of endogamous groups, as oommonly happens among other oastes, nor have they hardened into fixed hypergamous group¬ings, suoh as are exemplified by the Kulinism of Bengal. But running through the entire series of septs we find the usages of isogamy and hypergamy which have exeroised and oontinue to exercise a profound influenoe on Rajput sooiety. I sogamy or the law of equal marriage is defined by Mr. Ibbetson>il as the rule whioh arranges the septs of a given looality in a soale of sooial standing, and forbids a father to give his daughter to a man of any sept whioh stands lower than his own. Hypergamy or the law of superior marriage is the rule whioh oompels him to wed his daughter with a member of a sept whioh shall be aotually superior in rank to his own. In both cases a man usually does not scruple to take his wife, or at any rate his second wife, from a sept of inferior standing.

It will be readily seen how the working of these rules must have given rise to all sorts (If reciprocal obligations as between septs, and must have restrioted the number of available husbands in any particular locality. The men of a higher sept can take their wives from a lower sept, while a oorresponding privilege is denied to the women of the higher sept. Hence results a surpl us of women in the higher septs and competition for husbands sets in, leading to the payment of a high price for bridegrooms, and enormously increases the expense of getting a daughter married. Under these circum¬stances poor families are under a strong temptation to get rid of their female infants by poison or intentional neglect in order to be saved the expense of finding them suitable husbands or the disgrace of being compelled to marry them to men of lower degree.

Infanticide

There is no reason to believe that infanticide has ever been practised by the Rajputs of Bengal on the scale on which it has been known to occur in North-Western India. The sentiment which would tend to the commission of the crime is probably not so strongly developed among the Eastern Rajputs, who are, as has been inrlicated above, probably of much more mixed descent than the Rajputs of Rajpntima.

Marriages

The demand being for husbands, not for wives, it follows that the negotiations leading to marriage are opened by the father or guardian of the girl, who sends his family priest and family barber to the boyls house to make inquiries and to answer any questions that may be asked. Some¬times a professional match-maker, agua or ghatak, is employed. In any case these preliminary negotiations are known as aguai or bartalwn•. If these results are satisfactory, and the gil'l's family fiud that their offers are likely to be accepted, the same emissarie::> pay a second visit to the boy's house, accompanied by the girl's father, and bringing with them her horoscope, which is compared by the Brahmans of the two families with the horoscope of the boy in order to ascertain whether the match is likely to be auspicious. Wheu this point has been satisfActorily settled, the question of the bridegroom¬price (tilak and dalzejl to be paid by the girl's family is discu sed, and a certain proportion of it, usually half, is paid on the spot by way of olinching thfl bargain 'l'his is oalled bar chhenka or phaldan, and by receiving it the boy's people are deemed to biud themselves to marry him to no other woman. Sometimes the father of the boy also pays a small sum (sagun) as earnest money to the family of the girl.

This practice, however, is said to be unusual, and is only resorted to when it is thought that the girl's family may be disposed to evade fulfilment of their obligations. The first instalment vf the tilak or bridegroom¬price is paid by one of the girl's relations to the boy himself in the presence of the family Brahman. At the same time a oocoanut is presented to him and a mark (tilak) is made with curds on his forehead. Both the gift and the mark are supposed to bring good luok. '1'lle balance of the bridegroom-price is paid in two equal instalments later on-one before aud one after the marriage. On the occasion of paying the first instalment of tila!.-, presents are made to the Brahmans and barbers who have taken part in the proceedings, and a date is fixed for the celebration of the marriage, an intervul of fifteen days being usually allowed.

A few days before the wedding dhanl,atli takes place, a barber i Eent from the girl's house to the boy's with a present of unhusked rice. The boy's guardian takes this, mixes with it some rice of his own, and has the mixtUl'e parched. 'l'wo days before the wedding the women of the family scatter this parched rice about in the COUl't, yard, singing songs which :lre supposed to bring good luck. On the next day, tha.t is the day befortl the wedding, the rite of gilidluil'i is perform eu in the houses of the bride aDd bridegroom sepa.rately. The parents and nearest relations of the latter put on yellow clothes, and in the presence of the family prie ts wurship Glmesa, the deity, who presides over suceeS::i in life. The bridegroom is then smeared with oil, tUl'meric and ,qlti, offerIngs are made to the family gods, and the hair of the bridegroom's mother 01' his nearest female relative is anointed with oil. The same ceremony is gone through in the house of the bride, the only difference being that her family olothe themselves in red for the occasion. On the day of the marriage, but before the wedding procession is arranged, the ceremony of belonki mangna is often, though not necessarily, performed. The parents

of the betrothed couple distribute cakes to the neighbours, demanding in return small presents of money (belonkil .

The marriage procession is formed at the house of the bride-groom, and makes a somewhat noisy progress to the house of the bride. There the entire party is entertained. The bride and bridegroom are seated under a man oa or wedding canopy, and after the recital of appropriate mantms or texts, the family priest of the bride's household fills the bridegroom's right hand with sindlw, and makes a mark with it on the bride's forehead, the women of the family meanwhile singing songs to celebrate the event. Among the Hajputs of Tirhut this is deemed the binding portion of the ritual, and the praotioe of walking round the saored fire, usually considered essential in the marriage of the higher oastes, is said to be unknown. The married oouple then leave the mm'wa and go to the koMal' or house, where the family deity has been plaoed for the oooasion. They worship and make offorings to him, and this oonoludes the marriage. The bridegroom then returns to the

fanwasa or lodgings reserved for his party, while the bride remains in her own house. Early next morning they are brought out and eaoh is made to ohew betel with whioh has been mixed a tiny drop of blood drawn from the other's little finger. This usage in whioh we may trace an interesting survival of primitive ideas is oalled sinelt fOI't/a, the joining of love. When it is over the bride is taken to her husband's house where she remains. On the fourth day after her arrival she and her husband stand together on a yoke suoh as is used for oxen, and a washerwomau pours water over them. 'fhis sy illbolical washing is supposed to be the first oocasion on whioh the oouple see eaoh other by daylight after marriage. Among the Rajputs of North-Western India, and in soma parts of Behar, the bride and bria.E'groom do not live together until after a seoond oeremony (oalled gaun a, or with reference to the bride's 'going' to her husband's house) has been performed, whioh may take place one, three, five or even seven years after the marriage, and is fixed with reference to the physical development of the bride.

In Tirhut, however, the oustom of premature consum¬mation, mentioned by Buchanan as prevalent among the Rajpllts of Behar, seems to have been introd uced, and it is &aid to be unusual for a bride to be kept at home until she attains puberty. Another oustom conn eoted with marriage, whioh students of comparative ethnography will al'0 recognize as a survival of more primitive ideas, may be referred to here. In Ritjput families of Tirhut it is oonsidered oontrary to etiquette for a young married oouple to see eaoh other by day so long as the husband's parents are alive, and in partioular they must avoid being seen together by the hu band's parents, and mu t not speak to one another in their presenoe. . It is of oourse extremely diffioult to ascertain how far a rule of this sort is actually observed, but I am assured that young married oouples are very careful to avoid infringing it, although as they grow older their solioitude on this point is apt to wear off.

The remarriage of widows is strictly fOl'bidden among the Rajputs of Behar. Divoroe is also prohibited, and when a woman is taken in adultery, she is summarily expelled from the caste, and either becomes a prostitute or joins herself to some religious sect of more or less dubious morality. In certain cases, however, where a married couple find themselves unable to live in harmony together, a sepa.ration is arrived at by mutual consent, each agreeing to look upon the other as a parent. In such cases the wife returns to her father's house, and the husband marries again. This is not, however, looked upon as a divorce.

Religion

Rajputs are orthodox Hindus, and worship the Hindu divinities favoured by the sect to which they happen to belong. By the Surajbansi division, special honour is done to the sun, whom they regard as their eponymous ancestor. Among minor gods Bandi and Narsingh appear to be most in favour. Ancestors are worshipped with offerings of milk, flowers and rice. Mondays and Wednesdays are believed to be the most propitious days for this worship. On the 15th day of Asin married women offer cakes and oil to the souls of their mother-in-law, grandmother-in-law and great grandmother-in-Iaw. This custom, known as the Jitia puja, has obviously been copied from the 81'addlt celebrated in honour of the three immediate descendants. The popular explanation of it is that it is intended to express the gratitude that every married women ought to feel for her good fortune in getting a husband. Mr. Grierson, in Bellm' Peasant L~fe,• speaks of the jitiya puja as" a fast and worship performed by women on the 8th of the dark half of Kartik (late in October) for the benefit of their children. Further inquiry on the subject would perhaps bring out points of interest and might clear up the discre¬pancy of date.

Disposal of the dead

For religious and ceremonial purposes Rajputs employ Brah¬ mans, who are received on equal terms by other members of the sacred order. The dead arc burned and the ashe thrown into the Ganges or ones of its tributaries. Sradd/~ is performed on the thirteenth day after death, and on the fonrteenth a feast is given to the Brahmans of the neighbourhood. It is followed by the barki 81"addh on the first anni¬versary of the death, when the members of the dead man's family shave their heads and faces, and present a pinda to the deceased, while the Brahmans recite mantras. Then the priests and the mem¬bers of the family partake of a feast. It is said to be a tradition that the expenditure on this ceremony must not exceed half of that inclU'red on the original sl•addit. After the barklli the ta1]Jall or nit-tal'}Jan, a daily offering of water is presented regularly by all the sons of the deceased, and particularly by the eldest. This prac¬tice, however, is observed only by highly-educated Rajputs, who know their religious obligations in this matter. On the first fifteen days of Rsin the pitri paksh or ancestors' fortnight is observed with offerings of water to all deceased ancestors. If a man dies sonless, leaving a wife and daughter, the smdclh and the bal'ki are performed by one of them, the other ceremonies being comitted. Failing these the nearest agnate gotia will take upon himself these pious duties. In the eventof a man dying away from his people and being burned or buried without the proper rites, his body is burned in effigy by his relatives, and the other ceremonies ru:e performed in the usual fashion. When a man has died a sudden or violent death, it is thought right for his son to make a pilgrimage to Gya and perform the sracldh ceremony there in order to secure the repose of his soul.

Occpation and social status

The high-flown titles-Bhupal, Bhupati, Bhusur, Bahuja-in . . use among Rajputs, and the name chhatri itself indicate the exalted pretensions of the status. tribe and their traditions concerning their original occupation. Many Rajputs still cling to the belief that Government and the trade of arms are their proper business in life; and these notions lead them to reg9.rd education, and more especially the higher education, in much the same light as a medieval warrior looked upon the clerkly studies of his time. For this reason the Rajputs as a body have rather dropped behind in the modern struggle for existence, where book• learning counts for more than strength of arm, nnd the more intelligent members of the tribe are quite conscious that their position is by no means what it was in the classical ages of Hindu tradition. Their relations to the land still help them to maintain a show of respectability and importance.

Many of them are zamindars, and those who hold cultivating tenures claim in virtue of their caste a remission of rent of their homestead lands. Thejeth-miyat or headman of a Behar village is frequently a Rajput. He collects the rents and receives in return a yearly allowance, known as pagri, from the zamindar. Rajputs are never artisans, and it is unusual to find them engaging in any kind of trade. In theory their social status is second only to that of the Brahman, but in Bengal Proper, where great Rajput houses do not exist, popular usage would, I think, place them below the Baidya and the R ayasth. Even in Behar the Babhans claim precedence over them on the ground that they will not touch the handle (pw'iltath 01' lagna) of tbe 'lplougb, and tbat tbey use the full ~6panayan ritual when investing their children with thejaneo or sacred thread, whereas the Rajputs plough and milk cows with their own hands, and shuffie on thejcmeo in a rough-and-ready fashion when a boy gets married.

In respect of diet the R ajputs conform generally to the practice of high-caste IIindus. The flesh of the goat, the deer and the hare, the pigeon, quail and ortolan may alone he eaten, and these animals, if not killed in hunting, must he slaughtered in a particular way Uhata/ta) by cutting the head off at a single stroke. Fish is lawful food. Wine is supposed to be forbidden . As regards the taking of food from members of other castes, the following rules are ill force :¬

~ Rajput can:lOt take kachchi food, i.e., rice or ddZ or anything that 18 cooked WIth water from anyone hut a. Brahman. Pakki food, such as parched grain, sweetmeats and the like, he may take from a man of any caste higher than his own or from a Dha.nuk, Kurmi, RaMI', Lohar, Bal'hi, RumMr, Goala, Mallah, Hajjam, Mali, Sonar, Laheri, or Gareri, provided that no salt or turmeric has been used in the making. These condiments he will add himself. Water is governed by the rul es applicable to paltki food. R ajputs may not use the hookahs of any other caste, but may smoke tobacco prepared by men of any caste except the Dosadh, Dom, Chamar, Musahar and Dhobi.

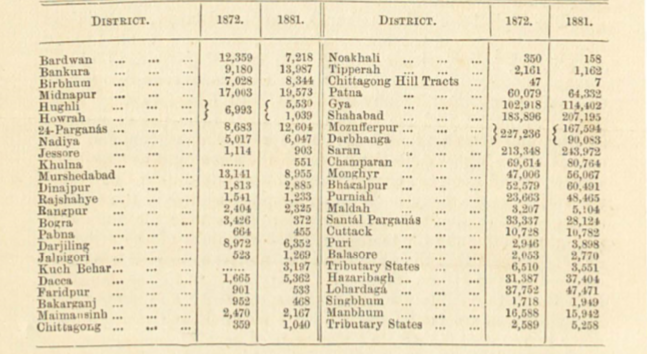

The following statement shows the number and distribution of RajputR in 1872 and 1881 :¬