Rajputana, 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Rajputana

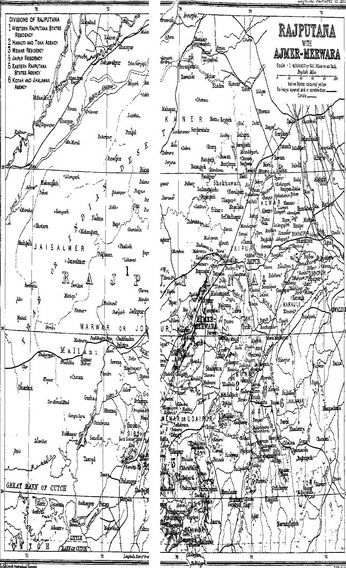

the country of the Rajputs ' , also called Rajasthan or Rajwara, ' the abode of the princes '). In the administrative nomen- clature of the Indian Empire, Rajputana is the name of a great terri- torial circle which includes eighteen Native States and two chiefships, together with the small British Province of Ajmer-Merwara.

These territories lie between 23 3' and 30 12' N. and 69 30' and 78 17' E,, with a total area of about 130,462 square miles. Included in the latter figure are the areas of Ajmer-Merwara (2,711 square miles), which, being British territory, has, for Census and Gazetteer purposes, been treated as a separate Province ; the two detached districts of Gangapur (about 26 square miles) and Nandwas (about 36 square miles), which belong respectively to the Gwalior and Indore Darbars, but, being surrounded by the Udaipur State, form an integral part of Rajputana- and, lastly, about 210 square miles of disputed lands. On the other hand, the areas of lands held by chiefs of Rajput- ana outside the territorial limits have been excluded, notably the three Tonk districts in Central India (about 1,439 square miles).

As traced on the map, Rajputana is an irregular rhomb, its salient angles to the north, west, south, and east respectively being joined by the extreme outer boundary lines of the States of Blkaner, Jaisalmer, Banswara, and Dholpur.

It is bounded on the west by the province of Smd ; on the north- west by the Punjab State of Bahawalpur ; and on the north and north-east by the Punjab. Its eastern frontier marches, first with the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh, and next with Gwalior, while its southern boundary runs across the central region of India in an irregu- lar zigzag line, separating it from a number of other Native States in Central India and the Bombay Presidency, and marking off generally the northern extension of that great belt of territory subject, directly or indirectly, to the Maratha powers Sindhia, Holkar, and the Gaikwar of Baroda.

It may be useful to give roughly the geographical position of the several States within this area. Jaisalmer, Jodhpur (or Marwar), and Blkaner form a homogeneous group in the west and north, while a tract called Shekhawati (subject to Jaipur) and Alwar are in the north-east. Jaipur, Bharatpur, Dholpur, Karauli, Bundi, Kotah, and Jhalawar may be grouped together as the eastern and south-eastern States. Those m the south are Partabgarh, Banswara, Dungarpur, and Udaipur (or Mewar), with Sirohi in the south-west. In the centre lie the British Province of Ajmer-Merwara, the Kishangarh State, the chief- ships of Shahpura and Lawa, and parts of Tonk. The last State con- sists of six isolated districts (three of which are, as already stated, in Central India), and cannot be said to fall into any one of these rough geographical groups.

The Aravalli Hills intersect the country almost from end to end by a line running nearly north-east and south-west, and about three- fifths of Rajputana lie north-west of this line, leaving two-fifths on the south-east. The heights of Mount Abu are close to aspects the sout h- w estern extremity of the range, while its north-eastern end may be said to terminate near Khetri in the Shekhawati country, though detached hills are traceable almost as far as Delhi.

Physical aspects

There are thus two main divisions namely, that north-west, and that south-east, of the Aravallis. The former stretches from Sind on the west, northwaid along the southern Punjab frontier to near Delhi on the north-east. As a whole, this tract is sandy, ill-watered, and unproductive, but improves gradually from a mere desert in the far west and north-west to comparatively fertile and habitable lands to- wards the north-east. The 'great desert,' forming the whole of the Rajputana-Smd frontier, extends from the edge of the Rann of Cutch beyond the Luni river northward ; and between it and what has been called the ' little desert ' on the east is a zone of less absolutely sterile country, consisting of rocky land cut up by limestone ridges, which to some degree protect it from the desert sands. The ' little desert ' runs up from the Luni river between Jaisalmer and Jodhpur into the northern wastes. The character of this region is the same everywhere. It is covered by sand-hills, shaped generally in long straight ridges, which seldom meet, but run in parallel lines, separated by short and fairly regular intervals, resembling the ripple-marks on a sea-shore upon a magnified scale. Some of these ridges may be two miles long, varying from 50 to 100 feet, or even more, in height j their sides are scored by water, and at a distance they look like substantial low hills.

Their summits are blown into wave-like curves by the action of the periodical westerly winds , they are sparsely clothed with stunted shrubs and tufts of coarse grass in the dry season, while the light lains cover them with vegetation. The villages within the desert, though always known by local names, cannot be reckoned as fixed habitations, for their permanence depends entnely on the supply of watei in the wells, which is constantly failing or turning brackish ; and as soon as the water gives out, the village must shift. A little water is collected in small tanks or pools, which become dry before the stress of the heat begins, and in places there are long marshes impregnated with salt, This is the character, with more or less variation, of the whole north and north-west of Rajputana. The cultivation is everywhere poor and precarious, though certain parts have a better soil than others, and some tracts are comparatively productive. Along the base of the Aravalli range from Abu north-east towards Ajmer, the submontane region lying immediately under the abiupt northern slopes and absorb- ing their drainage is well cultivated, where it is not covered by jungle, up to the Lfmi ; but north-west of this river the surface streams are mere rain gutters, the water in the wells sinks lower and lower, and the cultivation becomes poorer and more patchy as the scanty loam shades off into the sandy waste. As the Aravallis approach Ajmer, the continuous chain breaks up into separate hills and sets of hills.

Here is the midland country of Rajputana, with the city of Ajmer standing among the scattered hills upon the highest level of an open table-land, which spreads eastward towards Jaipur and slopes by degrees to all points of the compass. From Ajmer the Aravallis trend north-eastward, never reuniting into a chain but still serving to divide roughly, though less distinctly, the sandy country on the north and west from the kindlier soil on the south and east.

The second main division of Rajputana, south-east of the Aravallis, contains the higher and more fertile regions. It may be defined by a line starting from near Abu and sweeping round first south-eastward, and then eastward, along the northern fi on tiers of Gujarat and Malwa. Where it meets Gwalior, it turns northward, and eventually runs along the Chambal until that river enters the United Provinces \ it then skirts the British possessions in the basin of the Jumna as it goes north past Agra and Muttra up to the neighbourhood of Delhi. In contrast to the sandy plains which are the uniform feature, more or less modified, of the north-west, this south-eastern division has a very diversified character. It contains extensive hill ranges and long stretches of rocky wold and woodland ; it is traversed by considerable rivers, and m many parts there are wide vales, fertile table-lands, and great breadths of excellent soil. Behind the loftiest and most clearly defined section of the Aravallis, which runs between Abu and Ajmer, lies the Udaipur (Mewar) country, occupying all the eastern flank of the range, at a level 800 or 900 feet higher than the plains on the west. And whereas the descent of the western slopes is abrupt towards Marwar, on the eastern or Mewar side the land falls very gradually as it recedes from the long parallel ridges which mark the water-parting, through a country full of high hills and deep gullies, much broken up by irregular rocky emi- nences, until it spreads out and settles down into the open champaign of the centre of Udaipur. Towards the south-western corner of that State, the broken country behind the Aravallis is prolonged farthest into the interior ; and the outskirts of the main range do not subside into level tracts, but become a confused network of outlying hills and valleys, covered for the most part with jungle. This is the peculiar region known as the Hilly Tracts of Mewar. All the south-east of Rajputana is watered by the drainage of the Vindhyas, carried north-eastward by the Banas and Chambal rivers. To the north of the town of Jhalra- patan, the country rises by a very distinct slope to the level of a remarkable plateau called the Pathar, upon which lies a good deal of the territory of the Kotah and Bundi States. The surface of this table-land is very diversified, consisting of wide uplands, more or less stony, broad depressions, or level spaces containing deep black culti- vable soil between hills with rugged and irregular summits, sometimes barren and sometimes covered with vegetation. To the east the plateau falls very gradually to the Gwalior country and the catchment of the Betwa river , and to the north-east there is a very rugged region along the frontier line of the Chambal in the Karauli State, while farther northward the country smooths down and opens out towards the Bharatpur territory, whose flat plains belong to the alluvial basin of the Jumna.

Of mountains and hill ranges, the ARAVALLIS are by far the most important. Mount Abu belongs by position to these hills, and its principal peak, 5,650 feet above the sea, is the highest point between the Himalayas and the Nilgiris. The other ranges, though numerous, are comparatively insignificant. The cities of Alwar and Jaipur lie among groups of Mis more or less connected ; and in the Bharatpur State is a range of some local importance, the highest peak being AlTpur, 1,357 feet above sea-level. South of these are the Karauli hills, whose greatest height nowhere exceeds 1,600 feet; and to the south-west is a low but very well-defined range, running from Mandal- garh in Udaipur north-east across the Bundi territory to near Indar- garh in Kotah. These hills present a clear scarp for about 25 miles on their south-eastern face, and give very few openings for roads, the best pass being that in which lies the town of Bundi, whence they are called the Bundi hills. The MUKANDWARA range runs across the south- western districts of Kotah from the Chambal to beyond Jhalrapatan, and has a curious double formation of two separate ridges. No other definite ranges are worth mention j but it will be understood that the whole of Rajputana, excepting only the sandy deserts, is studded with occasional hills and isolated crags, and even so far as the south-west of the Jodhpur State, near Barmer, there are two which exceed 2,000 feet. All the southern States are more or less hilly, especially Banswara, Dungarpur, and the southernmost tracts of Mewar.

In the north-western division of Rajputana the only river of any consequence is the LUNT, which rises in the Pushkar valley close to Ajmer and flows west by south-west for about 200 miles into the Rann of Cutch. The GHAGGAR once flowed through the northern part of the Bikaner State, but now rarely reaches more than a mile or two west of the town of Hanumangarh. Its water is, however, utilized for irrigation purposes by means of two canals, which were constructed in 1897 at the joint expense of the Government of India and the Bikaner Darbar. The south-eastern division has a river system of importance. The CHAMBAL is by far the largest river in Rajputana, flowing through the

Province for about one-third of its course, and forming its boundary for another third. Its principal tributaries are the KAL! SINB, the PAR- BATI, and the BANAS. The last, which is next in importance to the Chambal, is throughout its length of 300 miles a river of Rajputana. It rises in the Aravallis near the fort of Kumbhalgarh, and collects all the drainage of the south-eastern slopes of those hills, as well as of the Mewar plateau , its principal tributaries are the Berach, Kothan, Khari, Mashi, Dhil, and Morel. Farther to the north is the BANGANGA, which, rising in Jaipur, flows generally east through Bharatpur and Dholpur into the District of Agra, where, after a course of about 235 miles, it joins the Jumna. The MAHI, a considerable river in Gujarat, runs for some distance through Banswara and along the border of Dungarpur in the extreme south, but it neither begins nor ends within Rajputana.

There are no natural fresh-water lakes, the only considerable basin being the well-known salt lake at SAMBHAR. There are, however, numerous artificial sheets of water, many of which are large, throughout the eastern half of the Province, more particularly in the Jaipur State. The oldest and most famous are, however, to be found in Mewar : namely, the DHEBAR LAKE, the Raj Samand at KANKROLI, and the Picrfola lake at Udaipur city.

Rajputana may be divided into two geological regions : namely, the eastern half including the Aravallis, and the western half. The Aravalli range, as it exists at present, is but the wreck of what must have been in former days a lofty chain of mountains, reduced to its present dimen- sions by subaerial denudation; and its upheaval dates back to very early geological times, when the sandstones of the Vindhyan system, the age of which is not clearly established but is probably not later than Lower Palaeozoic, were being deposited. The older rocks com- posing it are all of crystalline types, like the transition or Dharwar series of Southern India, and comprise gneisses and schists, with bands of crystalline limestone, slates, and quartzites. These have been divided into two systems, of which the lower, known as the Aravalli system, includes the gneisses, schists, and most of the slates. All these rocks have been greatly crushed and disturbed, and are thrown into sharp folds running m a direction parallel to the trend of the range , they are traversed by numerous dikes of intrusive granite, as well as of basic igneous rock. Of the gneiss but little is known, and it is doubtful whether any older than the transition series occurs in the range. Cal- careous bands are of common occurrence among the schists, and, where they are in contact with veins of intrusive granite, have been altered into a pure white crystalline marble, which is extensively quarried in several localities. The most famous of these quarries are at MAKRANA.

The slates at the northern end of the range are largely used for roofing purposes, and the copper and cobalt mines of Khetri are situated in the Aravalli schists, but have not been worked for many years. Over the schists and slates just described comes a series of slates, limestones, and quartzites, known as the Delhi system. The lower portion, con- sisting of slates and limestones, was formerly known as the Raialo group, and the upper portion (quartzites) is called the Alwar group the latter, however, frequently overlaps the former and rests directly on the Aravalh schists and slates. In the Bayana hills in Bharatpur the Alwar group has been divided as follows ,

(5) Wer quartzites and conglomerates.

(4) Damdama quartzites and conglomerates

(3) Bayana white quartzite and conglomerates.

(2) Badalgarh quartzite and shale.

(i) Nithahar quartzite and bedded trap

These groups are all separated by slight unconformities of denuda- tion and overlap, but the distinctions appear to be quite local. All the groups vary much in thickness, and are completely superseded near Nithahar by the Wer quartzites, which rest directly on the schists. Copper has been mined in the quartzites at Singhana near Khetn, and lead at the Taragarh hill close to Ajmer city. Vindhyan rocks of both the lower and upper divisions of that system are found east of the Aravalli range, their north-western limit being a line of hills running from Fatehpur Slkn south-west to near Chitor, and then south and south-east. The lower division consists of conglomerates at the base, formed of pebbles derived from the quartzites and schists, followed by red shales, sandstones, and limestones, while the upper division con- tains red false-bedded and ripple-marked sandstones, with bands of pebbles, and forms a plateau extending east beyond the limits of Rajputana. The only rocks on the eastern side of the Aravallis that are of later date than the Vindhyans are of igneous origin, belonging to the great outburst of Deccan trap which covers so large a portion of Central India. They are found in the extreme south-east, south of a line drawn from Nimach to Jhalrapatan, and conceal all the older formations beneath them.

West of the Aravallis are a few outliers of Lower Vindhyan rocks, resting unconformably upon the transition quartzites and slates, while in the low country to the north-west are large expanses of sandstones which are considered to belong to the Upper portion of this system. In the Jodhpur State numerous bare rocky hills rise from among the sand-dunes, consisting for the most part of volcanic rocks, rhyolites, and granites. The rhyolites, called the Mallani series from the district in which they were first found, are poured out upon an ancient land- surface formed of the Aravalh schists, but actual contacts between the two are very rare. They are pierced by dikes and bosses of granite of two varieties, one containing hornblende bat no mica (Siwana granite), and the other both hornblende and mica (Jalor granite), and are also traversed by numerous basic igneous rocks having the composition of olivme, dolerite, or diabase. In the desert a sequence of rocks newer than the Vindhyans is found. The oldest are boulder beds of glacial origin occurring at Bap in Jaisalmer, where they rest on Vindhyan limestones, and they are considered to repiesent the Talcher beds at the base of the Gondwana system. A similar boulder bed occurs at Pokaran in Jodhpur, also resting upon a glaciated surface of older rock ; but there is some doubt as to the relations of this bed to the Vindhyan sandstones, and it may be older than Talcher.

Farther to the west, in Jaisalmer territory, is a series of Jurassic rocks divided into the following five groups :

(5) Abur group. Sandstones, shales, and fossiliferous limestones ; the latter are buff-coloured, but weather red, and abound in yellow ammonites.

(4) Parihar group. Soft, white felspathic sandstones, weathering into a clean, sugary sand, and largely composed of fragments of transparent quartz.

(3) Bidesar group. Purplish and reddish sandstones, with thin layers of black vitreous ferruginous sandstone.

(2) Jaisalmer group. Thick bands of compact buff and light brown limestone, interstratified with grey, brown, and blackish sandstone, with some conglomerate.

(i) Lathi (or Banner ?) group. White, grey, and brown sandstones, interstratified with numerous bands of hard black and brown ferruginous sandstones and grit. Towards the base are some soft argillaceous sand- stones streaked and blotched with purple. Fragmentary plant remains and pieces of dicotyledonous wood have been found.

At Barmer in Jodhpur, there are some patches of sandstone and conglomerates, resting upon the Mallani lava-flows and considered to represent the Lathi group \ but they are quite isolated and their position in the series is somewhat doubtful. To the north-west of Jaisalmer town, and near Gajner in Blkaner, there is a considerable area of Lower Tertiary (Nummulitic) rocks. The deep wells that are necessary for reaching water in this desert also reveal their presence beneath the sand, and in some of these wells near Blkaner coal has been discovered interstratified with the Nummulitic beds l . Layers of unctuous clay or fuller's earth are also found at several localities in this formation, and ^the clay is exported under the name of multdni mitti. The more recent deposits of the Rajputana desert consist of calcareous conglo- merates, which are found in the larger river basins and denote a period when the flow of water was much greater than at present ; blown sand, 1 Records^ Geological Survey of India > vol. xxx, part in (1897), pp. 122-5. and calcareous limestone or kankar. The sand-dunes are all of the transverse type : i, e, they have their longer axes at right angles to the direction of the prevailing south-west wind. The sand contains large quantities of the calcareous casts of foraminiferaj and it is by the solu- tion of these that the beds of kankar are formed. The sand also contains salt, which is leached out by occasional rams and collects in depressions as at Pachbhadra in Jodhpur and the Sambhar Lake.

The most prominent constituent of the vegetation of Rajputana is the scrub jungle which shows forth, rather than conceals, the arid naked- ness of the land. The scrub consists largely of species of Capparis, ZizyphuS) Tamarlx^ Grewia, with such plants as Buchanama latifolia^ Cassia aunculata^ Woodfordia flonbunda^ Casearia tomentosa^ Diospyros montana^ Calotropis procera^ and Clerodendron phlomoides. West of the Aravalli Hills two cactaceous looking spurges. Euphorbia Royleana and E. neriifolia^ are common, but less so east of that range. Towards the western frontier occur Tecoma undulata and Acacia Jacquemontit, and plants which are characteristic of the and regions, such as Tamanx articulata and Myricaria germanica, Balanites Ro&burghii, Balsamo- dendron Mukul^ and Alhagi maurorum are also very common in Western Rajputana. Farther west the scrub becomes more and more stunted, spiny, and ferocious in its aspect, until it merges into the desert tracts of Sind. Trees form quite a secondary feature of the vegetation amidst the ubiquitous scrub Among the more common indigenous trees, which grow both east and west of the Aravallis, are Sterculia urens, Pro sop is spidgera, Dichrostachys cinerea, Acacia leucophloea^ Anogeissus pendula^ and Cordia Rothii^ although in Western Rajputana the term ' tree ' applied to some of these is rather a courteous acknowledgement of their descent than an indication of their size. The trees found more or less sparingly on the Aravallis and in Eastern Rajputana are Bombax malabaricuni) Semecarpus Anacardium, Erythrma suberosa, Bauhinia purpurea, Gmelma arborea^ Boswellia thunfera^ Butea frondosa^ Ter- minaha, tomentosa, and T. Arjuna. In Western Rajputana, in addition to those mentioned as occurring all over the region, are found Salva- dora persica and Acacia rupestris. Among the introduced or cultivated trees, the more common are Parkinsonia aculeata^ several figs such as Ficus glomerata^ mrgata^ religiosa, and bengalensis^ Acacia farnesiana and A. arabica^ Melia Azadtrachta, and the mulberry, tamarind, mango, pomegranate, peach, custard-apple, and guava. Climbing plants are exemplified by two species of Cocculus^ Cissampelos Pareira^ Mimosa rubricaulis, Vitis carnosa^ and V. latifolia. The herbaceous vegetation is for a considerable part of the year a dormant quantity, but during the brief rainy season, or in the neighbourhood of water, it springs to light. It consists of species of the following orders : Leguminosae^ Compo$itae Y Acanthaceae^ Boraginaceae, Malvaceae^ &c. Growing in water aie to be found Vallismria, Utricularia> and Potamogeton , and, among grasses, Androfogon, Atithisteria, and Cenchrus. The lower slopes of the Aravalhs show generally the same vegetation which the low hills to the east and the plains to the west exhibit; but higher up, in a moister atmosphere, there are found some species which could not exist in the dry hot plains. Among these are Aendes } Rosa Lyelht\ Girardmia heterophylla, Carissa Camndas^ Pongamia glabra^ Stercuha tolorata, Mallotits phihppmensis, and Dendrocalamus stnctus. A few ferns also occur on the range, such as Adiantum caudatum, A. limit- latuni) Cheilanthes fannosa, Nephrodium molle^ N. cicutarium, and Actimopteris radiata.

Theie are no wild animals peculiar to Rajputana, Lions must have been numerous about a hunared years ago, for Colonel Tod writes that Maharao Raja Bishan Singh of Bundi, who died in 1821, 'had slam upwards of one hunared lions with his own hand, besides many tigers.' Moreover, five lions were shot in Rajputana as recently as 1872 : namely, four near Jaswantpura in the south of Jodhpur, and a full-grown female on the western slope of Abu , and these are believed to have been the last of their kind in Rajputana There are still a fair number of tigers, chiefly in the Aravalh Hills and in parts of Alwar, Bundi, Jaipur, Karauh, Kotah, Sirohi, and Udaipur, while an occasional tiger is met with in every other State except Blkaner, Jaisalmer, and Kishangarh.

Leopards are common, and the sloth bear (Melursus ur sinus] is found in the Aravalhs and in other hills and forests, mainly in the south and south-east. Of deer, the sambar (Cervus unicolor) is met with in the same localities as the tiger and bear, though in greater abundance, while the chltal (C. a&is) frequents some of the lower slopes of the hills in Bundi, Kotah, Sirohi, Udaipur, &c. Antelope and gazelle are numerous in the plains, as also are nilgai (Boselaphus tragocamelus) in parts. Small game, such as snipe, quail, partridge, wild duck, and hare, can generally be obtained everywhere except in the desert. In the western States there are large numbers of the great Indian and of the lesser bustard, as well as several species of sand-grouse including the imperial, for which Blkaner is particularly famous.

In the summer the heat, except in the high hills, is great everywhere, and in the west and north-west very great. Hot winds and dust-storms are experienced more or less throughout the country, and in the sandy half-desert tracts are as violent as in any part of India, while in the southern parts they are tempered by hills, verdure, and water. In, the winter the climate of the north, especially on the Blkaner border, where there is sometimes hard frost at night, is much colder than in the southern States \ and from the great dryness of the atmosphere in these inland areas the change of temperature between day and night is sudden, excessive, and very trying. The heat, thrown off

VOL. xxi. G

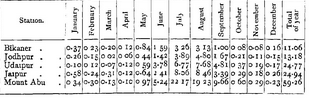

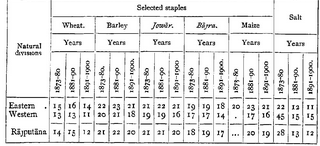

rapidly by the sandy soil, passes freely through the dry air, so that at night water may freeze in a tent where the thermometer marked 90 during part of the day. The following table gives the average mean temperature (in degrees F.) and the diurnal range at selected observatories during certain months :

These figures are for periods varying from twenty-one to twenty-five years ending with 1901, except in the case of Jodhpur, where they are for only five years

The rainfall is very unequally distributed throughout Rajputana The western portion comes very near the limits of that part of Asia which belongs to the rainless areas of the world, though even on this side the south-west winds bring annually a little ram from the Indian Ocean, In Jaisalmer and parts of Jodhpur and Bikaner, the annual fall averages scarcely more than 6 or 7 inches, as the rain-clouds have to pass extensive heated sandy tracts before reaching these plains, and are emptied of much of their moisture upon the high ranges in Kathiawar and the nearer slopes of the Aravallis. In the south-west, which is more directly reached, and with less intermediate evaporation, by the periodical rains, the fall is much more copious, and at Abu has on more than one occasion exceeded 100 inches, namely in 1875, 1881, 1892, and 1893. But, except in these south-west highlands of the Aravallis, the rain is most abundant in the south-east of Rajputana.

Along the southern States, from Banswara to Jhalawar and Kotah, the land gets not only the rains from the Indian Ocean, which sweep up the valleys of the Narbada and Mahl rivers across Malvva to the coun- tries about the Chambal, but also the remains of the moisture which comes up from the Bay of Bengal m the south-east ; and this supply occasionally reaches all Mewar. In this part of the country, if the south- west rains fail early, those from the south-east usually come to the rescue later in the season ; on the other hand, the northern part of Rajputana gets a scanty share of the winter rams of Northern India, while the southern part usually gets none at all, beyond a few gentle showers about Christmas. In the central tract, about Ajmer and towards Jaipur, the periodical supply of rain is very variable. If the eastern winds are strong, they bring good rains from the Bay of Bengal; whereas if the south-west monsoon prevails, the ram is comparatively late and light. Sometimes a good supply comes in from both seas, and then the fall is larger than in the eastern tract ; but it is usually much less. In the far north of Rajput- ana the wind must be very strong, and the clouds very full, to bring any appreciable supply from either direction. It may be said shortly that from Blkaner and Jaisalmer in the north-west to Banswara in the south, and Kotah and Jhalawar in the south-east, there is a very gradu- ally increasing rainfall from about 6 to 40 inches, the amount increasing very rapidly after the Aravallis have been crossed. The subjoined table gives the average annual rainfall (in inches) at five representative stations during the twenty-five years ending 1901

To this it may be added that the annual rainfall m the thiee eastern States (Bharatpur, Dholpur, and Karauli) vanes between 24 and 29 inches, in Kotah and Jhalawar between 3 r and 3 7 inches, and at the town of Banswara is about 40 inches. The greatest fall recorded in any one year was ovei 130 inches at Mount Abu in 1893, while in 1899 not one-hunaredth of an inch was registered at the rain-gauge stations of Khabha and Ramgarh in the west of the Jaisalmer State.

Earthquakes are not uncommon at Abu and, being accompanied with much rumbling noise, are somewhat alarming, but during recent years at any rate they have done no harm. In years of excessive rain- fall, the rivers sometimes cause damage and loss of life. For example, in 1875 the Banas rose in high flood and, in its passage past Tonk town, is said to have swept away villages and buildings far above the highest water-mark. Again, the Banganga river, till it was brought under control in 1895 by means of several irrigation works constructed by the Bharat- pur Darbar, has been responsible for much damage, not only in that State but in the adjoining District of Agra, notably in 1873, when villages were literally swept away by the floods, and Bharatpur city itself was saved with great difficulty, and again in 1884 and 1885.

History

The early history of the country now called Rajputana is, like that of other parts of India, somewhat obscure, and the materials for its reconstruction are scanty. The discovery of two rock-inscriptions of Asoka (about 250 B.C.) near BAiRAT-in the Jaipur State seems to show that his dominions extended westwards to, at any rate, this part of the country. In the second century B.C. the Bactrian Greeks came down from the north and north- west ; and among their conquests are mentioned the old city of Nagari (called Madhyamika) near Chitor, and the country round and about the Kali Smd river, while the coins of two of then kings, Apollodotus and Menander, have been found m the Udaipur State.

From the second to the fourth century A.D. the Sakas or Scythians were powerful, especially in the south and south-west ; and an inscription (dated about 150) at Girnar mentions a famous chief, Rudradaman, as ruler of Maru (Marwar) and the country round the Sabarmati, &c. The Gupta dynasty of MAGADHA ruled over parts of the Province from about the end of the fourth century to the beginning of the sixth century, when it was overthrown by the White Huns under their Raja Tora- mana. In the first half of the seventh century, Harshavardhana, a Rajput of the Vaisha or Bais clan, ruled at Thanesar ar\d Kanauj, and conquered the country as far south as the Narbada, including, of course, a great deal of Rajputana. At the time of the visit of the Chinese pilgrim, Hmen Tsiang (629-45), Rajputana fell within four main divi- sions which were then called Gurjjara (Bikaner, the western States, and part of Shekhawati), Vadan (the southern and some of the central States), Bairat (Jaipur, Aiwar, and a portion of Tonk), and Muttra (the three eastern States of Bharatpur, Dholpur, and Karauh). Included in the kingdom of Ujjain were Kotah, Jhalawar, and some of the outlying districts of Tonk.

Between the seventh and the beginning of the eleventh century several Rajput dynasties arose. The Gahlots (or, as they are now called, the Sesodias) migrated from Gujarat and occupied the south- western portion of Mewar, their earliest inscription in Rajputana being dated 646. Next came the Parihars, who began to rule at Mandor in Jodhpura few yeais later ; and they were followed in the eighth century by the Chauhans and the Bhatis, who settled down respectively at Sambhar and in Jaisalmer. Lastly, in the tenth century the Paramaras and the Solankis began to be powerful in the south-west. It is interesting to note that, of these Rajput clans, only three are now represented by ruling chiefs of Rajputana, namely the Sesodias, Bhatis, and Chauhans ; * and of these three, only the first two are still to be found m their original settlements, the Chauhans having moved gradually south-west and south-east to Sirohi, Bundi, and Kotah. Of the other Rajput clans now represented among the chiefs of Rajputana, the Jadons obtained a footing in Karauli about the middle of the eleventh century, though they had lived in the vicinity for a very long time; the Kachwahas came to Jaipur from Gwalior about 1128- the Rathors from Kanauj settled in Marwar in the beginning of the thirteenth century ; and the Jhala State of Jhalawar did not come into existence till 1838.

The first Musalman invasions (1001-26) found Rajput dynasties seated in all the chief cities of Northern India (Lahore, Delhi, Kanauj), but the march of Mahmud's victorious army across Rajputana, though it temporarily overcame the Solankis, left no permanent impres- sion on the clans. The latter were, however, seriously weakened by the feuds between the Solankis and the Chauhans, and between the latter and the Rathors of Kanauj, which give such a romantic colour to the traditions of the concluding part of the twelfth century. Never- theless, when Muhammad Ghori began his invasions, the Chauhans fought hard before they were driven out of Delhi and Ajmer in 1193, and Kanauj was not taken till the following year. Kutb-ud-dln garrisoned Ajmer, and the Musalmans appear gradually to have overawed, if they did not entirely reduce, the open country. They secured the natural outlets of Rajputana towards Gujarat on the south- west, and the Jumna on the north-east ; and the effect was probably to press back the clans into the outlying districts, where a more difficult and less inviting country afforded a second line of defence against the foreigner a line which they have held successfully up to the present day.

Indeed, setting aside for the present the two Jat States of Bharat- pur and Dholpur and the Muhamrnadan principality of Tonk, Rajputana may be described as the region within which the pure-blooded Rajput clans have maintained their independence under their own chieftains, and have kept together their primitive societies ever since their principal dynasties in Northern India were cast down and swept away by the Musalman irruptions. The process by which the Rajput clans were gradually shut up within the natural barrier of difficult country, which still more or less marks off their possessions, continued with varying fortune, their frontiers now receding, now again advancing a little, until the end of the fifteenth century. In the thirteenth century the rich southern province of Malwa was annexed to the Delhi empire ; and at the beginning of the fourteenth century, Ala-ud-dm Khilji finally subdued the Rajput dynasties in Gujarat, which also became an im- perial province. At the same time he reduced Ranthambhor, a famous fortress of the eastern marches, and sacked Chitor, the capital of the Sesodias, But, although the early Delhi sovereigns constantly pierced the country by rapid invasions, plundering and slaying, they made no serious impression on the independence of the chiefs. The fortresses, great circumvallations on the broad tops of scarped hills, were desperately defended and, when taken, were hard to keep. There was no firm foothold for the Musalmans in the heart of the country, though the Rajput territories were encircled by incessant war and often rent by internal dissensions. The line of communication between Delhi and Gujarat by Ajmer seems indeed to have been usually open to the imperial armies ; and the Rajputs lost for a time most of the great forts which commanded their eastern and most exposed frontier, and appear to have been slowly driven inward from this side. Yet no territorial annexations were very firmly held by the imperial governors from Delhi during the Middle Ages. Chitor was very soon regained and the other strongholds changed hands frequently.

When, however, the Tughlak dynasty went to pieces about the close of the fourteenth century, and had been finally swept away by Timur's sack of Delhi, two independent Musalman kingdoms were set up in Gujarat and Malwa. These powers proved more formidable to the Rajputs than the unwieldy empire had been, and throughout the fifteenth century there was incessant war between them. For a short interval, at the beginning of the sixteenth century, came a brilliant revival of Rajput strength. The last Afghan dynasty at Delhi was breaking up in the usual high tide of rebellion, and Malwa and Gujarat were at war with each other, when there arose the famous Rana Sangram Singh (Sanga) of Mewar, chief of the Sesodias. His talents and valour once more enlarged the borders of the Rajputs, and obtained for them something hke predominance in Central India. Aided by Medmi Rao, chief of Chanderi, he fought with distinguished success against both Malwa and Gujarat. In 1519 he captured Mahmud II ; and m 1526, in alliance with Gujarat, he totally subdued the Malwa state, and annexed to his own dominions all the eastern provinces of that kingdom, and recovered the strong places of the eastern marches, such as Ranthambhor and Khandhar. The power of the Rajputs was now at its zenith, for Rana Sanga was no longer the chief of a clan but the king of a country The Rajput revival was, however, as short-lived as it was brilliant.

In the year when Malwa was subdued, and one month before its capital surrendered, the emperor Babar took Delhi and extinguished the Pathan dynasty, so that Rana Sanga had only just got rid of his ancient enemy in the south, when a new and greater danger threatened him from the north. He marched, however, towards Bayana, which he took from the imperial garrison placed there, and Babar pushed down to meet him. At Khanua m Bharatpur, in March, 1527, the Rana, at the head of all the chivalry of the clans, encountered Babar's army and was defeated after a furious conflict, in which fell Hasan Khan, the powerful chief of the Mewati country, and many Rajputs of note. In this way the great Hindu confederacy was hope- lessly shattered; Rana Sanga died in the same year, covered with wounds and glory, and the brief splendour of united Rajasthan waned rapidly. In 1534 Bahadur Shah of Gujarat took Chitor, and recovered almost all the provinces which the Rana had won from Malwa ; and the power and predominance of the Sesodia clan were transferred to the Rathors of the west, where Maldeo, chief of Jodhpur, had become the strongest of all the Rajput rulers. The struggle which began soon after Babar's death, between Humayun and the Pathan Sher Shah, had relaxed the pressure of the Delhi power upon the clans from this side, and Maldeo greatly increased in wealth and territory. In 1544 he was attacked by Sher Shah in great force, but gave him such a bloody reception near Ajmer that the Pathan abandoned further advance into the Rathor country, and turned southward through Mewar into Bundel- khand, where he was killed before the fort of Kalinjar. It is clear that the victory at Khanua extinguished the last chance which the Rajputs ever had of regaining their ancient dominions in the rich plains of India. It was fatal to them, not only because it broke the war-power of their one able leader, but because it enabled the victor to lay out the foundations of the Mughal empire. A firmly consolidated government surrounding Rajputana necessarily put an end to the expansion, and gradually to the independence, of the clans ; and thus the death of Humayun in 1556 marks a decisive era in their history.

The emperor Akbar, shortly after his accession, attacked Maldeo, the Rathor chief, recovered from him Ajmer and several "other impor- tant places, and forced him to acknowledge his sovereignty. He then undertook to settle the whole region systematically. Chitor was again besieged and taken, with the usual grand finale of a sortie and massacre of the defenders. Udaipur was occupied, and though the Sesodias did not formally submit, they were reduced to guerrilla warfare in the Aravallis. In the east, the chief of the Kachwahas at Amber had entered the imperial service, while the Chauhans of Bundi were over- awed or conciliated. They surrendered the fort of Ranthambhor, the key to their country, and were brought with the rest within the pale of the empire. Akbar took to wife the daughters of two great Rajput houses ; he gave the chiefs or their brethren high rank in his armies, sent them with their contingents to command on distant frontiers, and succeeded in enlisting the Rajputs generally (save the Sesodias) not only as tributaries but as adherents. After him Jahanglr made Ajmer his head-quarters, whence he intended to march in person against the Sesodias who had defeated his generals m Mewar ; and here at last he received, in 1614, the submission of Rana Amar Singh of Udaipur, who, however, did not present himself in person. But though the Ranas never attended the Mughal court, they sent henceforward their regular contingent to the imperial army, and the ties of political associa- tion were drawn closer in several ways. The Rajput chiefs constantly entered the imperial service as governors and generals (there are said to have been at one time forty-seven Rajput mounted contingents), and the headlong charges of their cavalry became famous m the wars of the empire. Both Jahanglr and Shah Jahan were sons of Rajput mothers, and the latter in exile was protected at Udaipur up to the time of his accession, Their kinship with the clans helped these two emperors greatly in their contests for the throne, while the strain of Hindu blood softened their fanaticism and mitigated their foreign contempt for the natives of India.

When Shah Jahan grew old and feeble, the Rajput chiefs took their full share in the war between his sons for the throne, siding mostly with Dara, their kinsman by the mother's side , and Raja Jaswant Singh of Jodhpur was defeated with great slaughter in 1658 at Fateh- abad, near Ujjain, in attempting to stop Aurangzeb's march upon Agia. Aurangzeb employed the Rajputs in distant wars, and their contingents did duty at his capital, but he was too bigoted to retain undiminished the hold on them acquired by Akbar. Towards the end of his reign he made bitter, though unsuccessful, war upon the Sesodias and devastated parts of Rajputana ; but he was very roughly handled by the united Rathors and Sesodias, and he had thoroughly alienated the clans before he died. Thus, whereas up to the reign of Akbar the Rajput clans had maintained their political freedom, though within territorial limits that were always changing, from the end of the six- teenth century we may regard their chiefs as having become feudatories or tributanes of the empire ; and, if Aurangzeb's impotent invasion be excepted, it may be affirmed that from Akbar's settlement of Rajputana up to the middle of the eighteenth century the Rajput clans did all their serious warfare under the imperial banner in foreign wars, or in the battles between competitors for the throne.

When Aurangzeb died, they took sides as usual. Shah Alam Baha- dur, the son of a Rajput mother, was largely indebted for his success to the swords of his kinsmen , and the obligations of allegiance, tribute, and military service to the empire were undoubtedly recognized as defining the political status of the chief so long as an emperor existed who could exact them. After the death of Aurangzeb, the Rajputs attempted the formation of an independent league for their own defence, m the shape of a triple alliance between the three leading clans, the Sesodia, Rathor, and Kachwaha; and this compact was renewed when Nadir Shah threw all Northern India into confusion.

But the treaty contained a stipulation that, in the succession to the Rathor and Kachwaha chiefships, the sons of a Sesodia princess should have preference over all others ; and this attempt to set aside the rights of primogeniture was the fruitful source of disputes which soon split up the federation In the rising storm which was to wreck the empire, the chiefs of Jodhpur and Jaipur held their own, and indeed increased their territories in the general tumult, until the wasting spread of the Maratha freebooters brought in a flood of anarchy that threatened every political structuie in India. The whole penod of 151 yeais from Akbar's accession to Aurangzeb's death was occupied by four long and strong reigns, and for a century and a half the Mughal was fairly India's master. Then came the ruinous crash of an overgrown cen- tralized empire whose spoils were fought over by Afghans, Sikhs, Jats, revolted viceroys, and rebellious military adventurers. The two Saiyids governed the empire under the name of Farrukh Siyar ; Jodhpur was invaded, and the Rathor chief was forced to give a daughter to the titular emperor. He leagued with the Saiyids until they were murdered, when, in the tumult that followed, he seized Ajmer in 1721.

About thirty years later, there were disputes regarding the succession to the Jodhpur chiefship, and one of the claimants called in the Ma- rathas, who got possession of Ajmer about 1756 , and from this time Rajputana became involved in the general disorganization of India. The primitive constitution of the clans rendered them quite unfit to resist the piofessional armies of Marathas and Pathans, and their tribal system was giving way, or at best transforming itself into a disjointed military feudalism. About this period, a successful leader of the Jat tribe took advantage of the dissolution of the imperial government to seize territories close to the right bank of the Jumna and to set up a dominion. He built fortresses and annexed districts, partly from the empire and partly from his Rajput neighbours, and his acquisitions were consolidated under his successors until they developed into the present Bharatpur State. The Rajput States very nearly went down with the sinking empire. The utfer weakness of some of the chiefs and the general disorder following the disappearance of a paramount authority in India dislocated the tribal sovereignties and encouraged the building of strongholds against predatory bands, the rallying of parties round petty leaders, and all the general symptoms of civil con- fusion. From dismemberment among rival adventurers the States were rescued by the appearance of the British on the political stage of Northern India. In 1803 all Rajputana, except the remote States in the north and north-west, had been virtually brought under by the Marathas, who exacted tribute, annexed territory, and extorted sub- sidies. Sindhia and Holkar were deliberately exhausting the country, lacerating it by ravages or bleeding it scientifically by relentless tax- gatherers; while the lands had been desolated by thirty years of in- cessant war.

Under this treatment the whole group of ancient chieftainships was verging towards collapse, when Lord Wellesley struck in for the British interest. The victories of Generals Lake and Wellesley permanently crippled Sindhia's power in Northern India, and forced him to loosen his hold on the Rajputana States in the east and north-east, with two l of which the British made a treaty of alliance against the Marathas. In

1 Bharatpur in September and Alwar in November, 1803. 1804 Holkar marched through the heart of Rajputana, attempted the fort of Ajmer, and threatened our ally, the Maharaja of Jaipur. Colonel Monson went against him and was enticed to follow him southward beyond Kotah, when the Marathas suddenly turned on the English commander and hunted him back to Agra. Then Holkar was, in his turn, driven off by Lord Lake, who smote him blow on blow ; but Lake himself failed signally in the dash which he made against the fort of Bharatpur, where Holkar had taken refuge under protection of the Jat chief, who broke his treaty with the British and openly suc- coured their enemy. The fort was afterwards surrendered, a fresh treaty being concluded \ and Holkar was pursued across the Sutlej and compelled to sign a treaty which stripped him of some of his annexa- tions in Raj pu tana.

Upon Lord Wellesley's departure from India policy changed, and the chiefs of Rajputana and Central India were left to take care of themselves. The consequence was that the great predatory leaders plundered at their ease the States thus abandoned to them, and became arrogant and aggressive towards the British power. This lasted for about ten years, and Rajputana was desolated during the interval ; the roving bands increased and multiplied all over the country into Pindari hordes, until in 1814 Amir Khan was living at free quarters in the heart of the Rajput States, with a compact army estimated at 30,000 horse and foot and a strong force of artillery. He had seized some o the finest districts in the east, and he governed them with no better civil institution than a marauding and mutinous force. The States of Jodhpur and Jaipur had brought themselves to the brink of extinction by the famous feud between the two chiefs for the hand of a princess of Udaipur, while the plundering Marathas and Pathans encouraged and strenuously aided them to ruin each other until the dispute was compromised upon the basis of poisoning the girl,

In 1811 Sir Charles Metcalfe, Resident at Delhi, reported that the minor chiefs urgently pressed for British intervention, on the ground that they had a right to the protection of the paramount power, whose obvious business it was to maintain order, but it was not till 1817 that the Marquis of Hastings was able to carry into action his plan for breaking up the Pindari camps, extinguishing the predatory system, and making political arrangements that should effectually prevent its revival. Lawless banditti were to be put down ; the general scramble for territory was to be ended by recognizing lawful governments once for all, and fixing their possessions, and by according to each recog- nized State British protection and terntonal guarantee, upon condition of acknowledging our right of arbitration and general supremacy in external disputes and political relations. Upon this basis overtures for negotiations were made to all the Rajput States, and in 1817 the British armies took the field against the Pindans. Amir Khan dis- banded his troops, and signed a treaty which confirmed him in possession of certain districts held in grant, and by which he gave up other lands forcibly seized from the Rajputs. His territories, thus marked off and made over, constitute the existing State of Tonk.

Of the Rajput States (excluding Alwar, whose treaty, as already mentioned, is dated November, 1803), the first to conclude treaties were Karauli (in November) and Kotah (m December, 1817); and by the end of 1818 similar engagements had been entered into with all 1 the other States, with clauses settling the payment of Maratha tributes and other financial charges. There was a great restoration of plundered districts and rectification of boundaries. Smdhia gave up Ajmer to the British, and the pressure of the Maratha powers upon Rajputana was permanently withdrawn.

Since then the political history of Rajputana has been comparatively uneventful. In 1825 a serious disturbance over the succession to the chiefship of Bharatpur caused great excitement, not only locally, but in the surrounding States, some of them even secretly taking sides in the quarrel which threatened to spread into war. Accordingly, with the object of preserving the public peace, the British Government determined to displace a usurper and to maintain the rightful chief ; and Bharatpur was stormed and taken by British troops on Jan- uary 1 8, 1826. In 1835 the prolonged misgovernment of Jaipur cul- minated in serious disturbances which the British Government had to compose; and in 1839 a force marched to Jodhpur to put down and conciliate the disputes between the chief and his nobles which dis- ordered the country. The State of Kotah had been saved from ruin and raised to prosperity by Zahm Singh, who, though nominally minister, really ruled the country for fifty years ; and the treaty of 1817 had vested the administration of the State in Zalim Singh and his descendants. But this arrangement naturally led to quarrels between the latter and the heirs of the titular chief, wherefore in 1838 a part of the Kotah territory was marked off as a separate State, under the name of Jhalawar, for the direct descendants of Zalim Singh, a Rajput of the Jhala clan. On the deposition in 1896 of the late chief of Jhalawar, there were found to be no direct descendants of Zalim Singh , and the Government of India accordingly decided that part of the territory which had been made over in 1838 should be restored to Kotah, and that the remaining districts should be formed into a new State for the descendants of the family to which Zalim Singh belonged. This dis- tribution of territory came into effect in 1899.

1 Except Sirohi, whose treaty is dated September, 1823 ; and, of course, Jhalawar, which did not come into existence till 1838 When the Mutiny of the Bengal army began in May, 1857, there were no European soldiers in Rajputana, except a few invalids recruit- ing their health on Mount Abu. Naslrabad was garrisoned by sepoys of the Company's forces ; and four local contingents, raised and com- manded by British officers but mainly paid from the revenues of certain States, were stationed at Deoh, Beawar, Erinpura, and Kher- wara. The chiefs of Rajputana were called upon by the Governoi- General's Agent (General George Lawience) to preserve peace within their borders and collect their musters ; and in June the troops of Bharatpur, Jaipur, Jodhpur, and Alwar were co-operating in the field with the endeavours of the British Government to maintain order in British Districts and to disperse the mutineers. But these levies, however useful as auxiliaries, were not strong enough to take the offensive against the regular regiments of the mutineers. Moreover, the interior condition of several of the States was critical : their terri- tory, where it bordered upon the country which was the focus of the Mutiny, was overrun with disbanded soldiers , the fidelity of their own mercenary troops was questionable, and their predatory and criminal tribes soon began to harass the country-side In this same month (May, 1857) the artillery and infantry mutinied at Naslrabad; the Kotah Contingent was summoned from Deoli to Agra, where it joined the Nlmach mutineers m July , and the Jodhpur Legion at Ennpura broke away in August. The Merwara Battalion and the Mewar Bhll Corps, recruited for the most part from the indigenous tribes of Mers and Bhils respectively, were the only native troops in all Rajputana who stood by their British officers. In the important centre of Ajmer, General Lawience maintained authority with the aid of a detachment of European troops from Deesa, of the Merwara Battalion, and of the Jodhpur forces ; but throughout the country at large, from the confines of Agra to Sind and Gujarat, the States were left to their own re- sources, and their conduct and attitude were generally very good. In Jaipur tranquillity was preserved ; the Blkaner chief continued to render valuable assistance to British officers in the neighbouring Districts of the Punjab, and the central States kept orderly rule.

In the western part of Jodhpur some trouble was caused by the rebellion or contumacy of Thakurs, especially of the Thakur of Awa, who had taken into his service a body of the mutinied Jodhpur Legion , but the ruling chief continued most loyal Towards the south, the territory of Mewar was considerably disturbed by the confusion which followed the mutinies at Nlmach, by the continual incursions of rebel parties, and by some political mismanagement ; but, on the whole, this tract of country remained comparatively quiet, and the Maharana hospitably sheltered several European families that had been forced to flee from Nlmach. The Haraoti chiefs of Kotah, Bundi, and Jhalavvar kept their States in hand, and sent forces which took charge of Nimach for some six weeks during the early days when the odds were heaviest against the British in Northern India. After the fall of Delhi this period of suspense ended ; and the States could afford to look less to the question of their own existence in the event of general anarchy, and more to the duty of assisting the British detachments. Jaipur at once joined heartily in the exeitions of Government to pacify the country. In Jodhpur the chief had his hands full of work with his own unruly feudatories, and the British assisted him in reducing them, In Kotah the troops were profoundly disaffected and beyond the control of the chief , they murdered the Political Agent and broke into open revolt. The adjoining chief of Bundi gave piactically no aid, partly through clannish and political jealousies of Kotah ; but the Mahaiaja of Karauli, who greatly distinguished himself by his active adherence to the British side throughout 1857, sent troops to the aid of his relative, the Kotah chief, when he was besieged in his own fort by his mutineers, and held the town until it was taken by assault by a British force in March, 1858, an event that marked the extinction of armed rebellion in Rajputana.

The year 1862 was notable for the giant to every ruling chief in the Province of a sanad guaranteeing to him (and his successors) the right of adoption m the event of failure of natural heirs , and this was followed by a series of treaties or agreements relating to the mutual extradition of persons charged with heinous offences, and providing for the suppression of the manufacture of salt and the abolition of the levy of all transit-duty on that commodity. During the last forty years great progress has been made. The country has been opened out by railways and roads, and life and property are more secure. Regular courts of justice, schools, colleges, hospitals, and well-managed jails have been established , the system of land revenue administration has been improved, petty and vexatious cesses have been generally abor lished, and, m several States, regular settlements, on the lines of those in British India, have been introduced.

Rajputana abounds in objects of antiquarian interest, but hitherto very little has been done to survey, describe, or preserve these links with the past.

The earliest remains are the rock-inscriptions of the great Mauryan king, Asoka, discovered at BAIRAT in Jaipur ; the ruins of some Buddhist monasteries at the same place ; and two stufas and a frag- mentary inscription of the third century B. c. at Negari near CHITOR. At Kholvi in the Jhalawar State is a series of rock-cut temples, interest- ing as being probably the most modern group of Buddhist caves in India ; they are believed to date from A. D. 700 to 900.

Of Jain structures, the most famous are the two well-known temples at^Delwara near ABU, of the eleventh and thirteenth century respec- tively, and the Kirtti Stambh, or ' tower of fame,' of about the same age at CHITOR, which have just been repaired under the general direc- tion of the Government of India. The oldest Jam temples are, how- ever, those near Sohagpura in Partabgarh, at Kalinjara in Banswara, and at one or two places in Jaisalmer and Sirohi, while remains exist at Ahar near Udaipur, and at Rajgarh and Paranagar in Alwar.

Among the earliest specimens of Hindu architecture must be men- tioned the stone pillar at BAYANA with an inscription dated A. D. 372 ; the remains of the chaorl or hall at MUKANDWARA, of the fifth century , and the ruined temples at Chandravati near JHALRAPATAN, of the seventh century. Noteworthy examples of military architecture are the forts of Chitor and Kumbhalgarh in Udaipur ; Ranthambhor in Jaipur ; Jalor and Jodhpur in Mar war ; Birsilpur in Jaisalmer, said to have been built in the second century ; Vasantgarh in Sirohi , Bijaigarh in Bharatpur ; Tahangarh in Karauh ; and Gagraun in Kotah. The most exquisitely carved temples are to be found in the Udaipur State at Barolli and at Nagda near the capital, the former of the ninth or tenth, and the latter of the eleventh century. Another celebrated building is the Jai Stambh or ' tower of victory ' at Chitor, built in the middle of the fifteenth century.

The Muhammadans have left a few memorials in the shape of mosques and tombs, chiefly in Jodhpur and Alwar; but they are of little interest. The earliest appears to be a mosque at Jalor, attributed to Ala-ud-dm Khilji.

Population

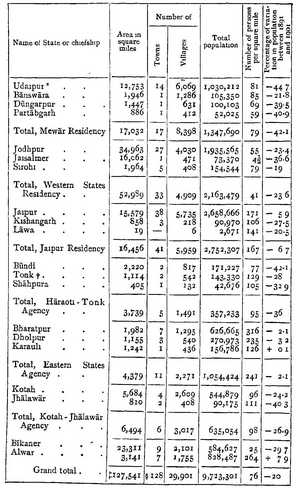

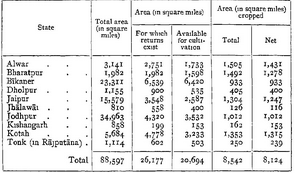

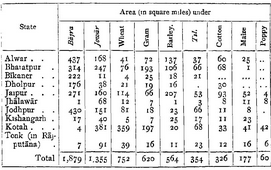

Rajputana is made up of eighteen States and two chiefships, and the population at each of the three enumerations was : (1881) 10,100,542,

Population ^ l89 ^ I2 > 220 >343> and (1901) 9,723,301. In- cluded in the figures for 1891 and 1901 are the inhabitants L of small tracts belonging to the Central India chiefs of Gwalior and Indore, but geographically situated in Mewar ; white, on the other hand, the population J of Tonk's three districts in Central India has been excluded throughout. Further, it is necessary to men- tion that the Census of 1901 was the first complete one ever taken in the Province At the two earlier enumerations the Girasias of the Bhakar, a wild tract in Siiohi, and the Bhils of Mewar, Banswara, and Dungarpur were not regularly counted, but their number was roughly estimated from information given by the illiterate headmen of their villages ; and these estimates have been included in the figures for 1 88 r and 1891. In some cases the headman gave what he believed to be the number of huts in his village (when four persons, two of each sex, were allowed to each hut), while at other times he made a guess

1 18,118 m 1891 and 11,407 in 1901.

3 167,850 in 1881 ; 181,135 in 1891 ; and 129,871 in 1901, at the total population, and his figures were duly entered. This was rendered necessary by the extreme aversion displayed by these shy and timid tribes to the counting of men and houses. The wildest stories were in circulation as to the objects of the Census, Some of the Bhlls thought that the Government of India were in search of young men for employment in a foreign war, or that the idea was to raise new taxes ; while, in 1891, others feared that they were going to be seized and thrown as a propitiatory sacrifice into a large artificial lake then being constructed at Udaipur.

Consequently, the Bhlls and Girasias were left unenumerated, and the census figures for 1881 and 1891 must be considered as only approximate. But, such as they are, they show an increase in popula- tion during that decade of nearly 2 1 per cent., compared with about 9 per cent, for the whole of India; while between 1891 and 1901 there was a decrease of nearly 2^ million inhabitants, or about 20 per cent. The decade preceding the Census of 1891 was one of prosperity and steady growth, but the apparent increase in population was probably due, to some extent, to improved methods of enumeration. Between 1891 and 1901 the country suffeied from a succession of seasons of deficient or ill-distributed rainfall , and though it did not perhaps lose as heavily as the census figures suggest, the loss was undoubtedly very great, and the main cause was the disastrous famine of 1899-1900 and its indirect results, lower birth-rate and increased emigration. Fever epidemics broke out in 1892, 1899, and 1900, the most virulent of all being that following the heavy rainfall of August and September, 1900, which was aided in its ravages by the impaired vitality of the people.

Vital statistics scarcely exist; but the general consensus of opinion appears to be that the mortality from fever between August, 1900, and February, 1901, exceeded that caused by want of food in the period during which famine conditions prevailed. A reference to the last column of the table on the next page will show that the only States in which an increase in population occurred were Alwar and Karauli, and that the decrease was greatest in Bundi, Dungarpur, Jaisalmer, Jhalawar, Partabgarh, and Udaipur, and least in Bharatpur, Dholpur, and Jaipur. Alwar has benefited for some years by a careful and wise administration, and the famine was less severely felt there and in the three eastern States (Bharatpur, Dholpur, and Karauli) than in other parts of Rajputana. In considering the figures for Dungarpur and Udaipur, it should be borne in mind that the population in 1891 included a large estimated (probably over-estimated) number of Bhlls \ but at the same time there is no doubt that both States lost very heavily in the famine. The figures for Jhalawar require a word of explanation. As mentioned above, this State was remodelled in 1899, and when the Census of 1901 had been taken, an attempt was made to work out

t Rajputana districts only

t Th!S is the area of the several States and chiefships in 1901, excludme- about 210 square miles of disputed lands

The town of Sambhar is under the joint jurisdiction of Jaipur and Jodhpur, and has been counted only once in the grand total. from the old census papers the population in 1891. This was reported to be 151,097, which meant a loss during the succeeding ten years of 40 per cent, of the people \ but some mistake appears to have been made in the calculation, for it is difficult to believe that the State, which was under British management from 1896 to 1899, and in which the famine was not severely felt, while the relief measures and administration generally were satisfactory, lost so heavily.

The 128 towns contained 288,696 occupied houses and 1,410,192 inhabitants, or nearly 5 persons per house ; and the urban population was thus 14-5 per cent, of the total, compared with 10 per cent, for India as a whole. The principal towns are the cities of JAIPUR (popu- lation, 160,167), the sixteenth largest in India; JODHPUR (79,109); ALWAR (56,771); BIKANER (53,075); UDAIPUR (45,976); BHARATPUR (43,601) ; TONK (38,759); and KOTAH (33,657), all capitals of States and all (except Udaipur) municipalities.

The rural population numbered 8,313,109, distributed in 29,901 villages containing 1,622,787 occupied houses, thus giving about 54 houses per village and slightly more than 5 persons per house. The average population of a village is 278, varying from 335 in the western States, where scarcity of water and insecurity of life have compelled people to gather together in certain localities, to 153 in the southern States, which contain a large Bhll population living in small hamlets scattered over an extensive area of wild country. These Bhll hamlets are called pals, and consist of a number of huts built on separate hillocks at some distance from each other; elsewhere the villages are usually compact collections of buildings.

Rajputana supports, on an average, 76 persons per square mile : namely, 35 in the sandy plains of the west, 79 in the more fertile but broken and forest-clad country of the south, and 165 in the eastern division, which is watered by several rivers and has a fair rainfall and a good soil. The most densely populated State is Bharatpur, bordering on the Jumna, with 316 persons per square mile; and the lowest density (in all India), 4-| per square mile, is recorded in the almost rainless regions of Jaisalmer. Within the States, the density in the several districts varies considerably; thus in Jodhpur, it is TOO per square mile in the north-east, and 10 in the west ; in Jaipur, 332 in the north-east, and 92 in the south-west; and in Alwar, 430 m the east, and 166 in the south-west. Throughout Rajputana the relation between rainfall and population seems to be singularly close.

Of the total population in 1901, 97*6 per cent, had been born in Rajputana, and immigrants from other parts of India (chiefly the Punjab, the United Provinces, Central India, Ajmer-Merwara, and the Bombay Presidency) numbered 233,718. On the other hand, the number of persons born in Rajputana but enumerated elsewhere in

VOL. XXI. H India was 900,224, so that, in this interchange of population, there was a net loss to Rajputana of 666,506 persons. But m the western States emigration is an annual event, whatever be the nature of the season, as there is practically but one harvest, the khanf, and as soon as it is gathered in September or October large numbers of people leave every year to find employment in Smd, Bahawalpur, and else- where, usually returning shortly before the rains are expected to break Moreover, the recent famine caused more than the usual amount of emigration. Lastly, the traders known as Marwans, who were born in Rajputana and have their homes and families theie, play an important part m the commerce of India ; and there is hardly a town where the * thrifty denizen of the sands of Western and Northern Raj- putana has not found his way to fortune, from the petty grocer's shop in a Deccan village to the most extensive banking and broking con- nexion in the commercial capitals of both east and west India. 5

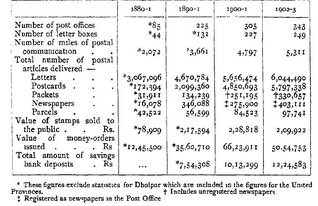

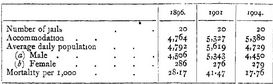

No vital statistics are recorded for Rajputana as a whole ; but the registration of births and deaths was, in 1904, attempted m ten entire States and one chiefship, having a total area of 53,178 square miles and a population of 3> 5 I >555, and at the capitals of six other States and two small towns which together contain 330,660 inhabitants. The mortality statistics are believed to be more accurate than those of births, but, except perhaps in some of the larger towns, both sets of figures are unreliable.

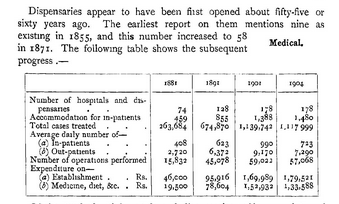

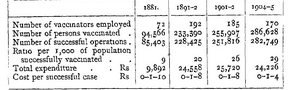

The principal diseases treated in the hospitals are malarial affections, ulcers and abscesses, diseases of the skin or eye, respiratory and rheumatic affections, diseases of the ear, and diarrhoea and dysentery. Malarial and splenic affections account for more than 18 per cent of the cases, and the variations in the different States or divisions are hardly worth noting, though perhaps the large proportion in the dry climate of Blkaner and the smaller m the more moist eastern States are rather contrary to the general opinion. Ulcers and abscesses account for nearly 12 per cent., and seem most prevalent in the centre and east, while diseases of the skin (also about 12 per cent.) are especially frequent in the western States, possibly owing to the want of water for cleansing purposes. Diseases of the eye are admitted in largest numbers in the centre, east, and south, while respiratory affections are less frequent in the west than elsewhere. Cholera and small-pox visitations occur periodically ; but as regards the latter, the effects of vaccination are everywhere becoming apparent, and those who most oppose the operation are not unfrequently convinced, when too late, by the fate of their own chilaren and the escape of those of their neighbours, of their error in neglecting vaccination.

Plague is believed to have made its first appearance m Rajputana in 1836. It broke out with great virulence at Pali, a town of Jodhpur, about the middle of July, and extended thence to Jodhpur city, Sojat, and several other places in Marwai, as well as to a few villages in the Udaipur State; and it appears to have finally disappeared at the beginning of the hot season of 1837. The fact that the disease first started among the cloth-stampers of Pah led to the supposition that it was imported m silks from China. An interesting account of the outbreak, and of the measures taken to combat it and prevent its spread, will be found at pp. 148-69 of the General Medical History of Rajftttana^. The present epidemic started in Bombay in 1896, but, excluding a few cases discovered at railway stations, did not extend to Rajputana till November, 1897, when it appeared in five villages of Sirohi and lasted till Apnl, 1898. Between October, 1896, and the end of March, 1905, there have been 37,845 seizures and 31,980 deaths in Rajputana. No cases have been reported from Bundi, Dfmgarpur, Jaisalmer, and Lawa, while Kishangarh shows but one and Blkaner three. Two-thirds of the deaths have occurred in Alwar, Jaipur, and Mewar, but the percentage of deaths to total population is highest in Partabgarh and Shahpura.

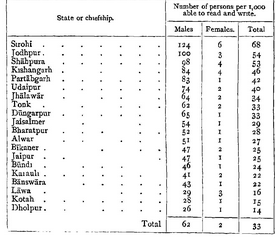

Of the total population in 1901, more than 52 per cent, were males, or, put in another way, for every 1,000 males there were 905 females, compared with 963 for the whole of India; and in each of the four mam religions this excess of males was observable, except among the Jams, where females slightly predominated. Various theories have been advanced to explain the difference m the proportion of the sexes but there is no reason to believe that it is due, at any rate to any appreciable extent, to female infanticide, though this practice was once very prevalent in Rajputana. An examination of the census statistics shows that between the ages of one and two there were more female than male infants, even among the Hindus, and that females exceeded males among the Musalmans up to the age of four, and among the Jains and Animists up to five.

Dealing next with the population according to civil condition, it is found that 48 per cent, of the males were unmarried, 43 married, and 9 widowed, and that the similar figures for females were 30, 50, and 20 respectively. The relatively low proportion of spinsters and the high proportion of widows are results of the custom which enforces the early marriage of girls and discourages the remarriage of widows.

Infant marriages still prevail to some extent, but are less common

than they used to be, and this is largely attributable to the efforts

of the Walterkrit Rajputra Hitkarmi Sabha. This committee is named

after the late Colonel Walter, who was the Governor-General's Agent

in Rajputana in 1888. On previous occasions attempts had been

made to settle the question of marriage expenses with a view to

1 By Colonel T. H. Hendley, I.M.S. (Calcutta, 1900).

H 2 suppress infanticide among the Rajputs, but they failed because no uniform rule was ever adopted for the whole country. In 1888 Colonel Walter convened a general meeting of representatives of almost all the States to check these expenses, The co-operation of the chiefs having been previously secured, the committee had no great difficulty in drawing up a set of rules for the regulation of marriage and funeral expenses, the ages at which marriages should be contracted, and other cognate matters. These rules, which were passed unani- mously and widely distributed in the various States, where local com- mittees of influential officials were appointed by the Darbars to see to their proper observance, laid down the maximum proportion of a man's income that might be expended on (a) his own or his eldest son's marriage, and (ft) that of other relatives, together with the size of the wedding party and the tydg or largess to Charans, Bhats, Dholis, and others. It was also laid down that no expenditure should be incurred on betrothals, and the minimum age at marriage was fixed at 1 8 for a boy and 14 for a girl. It was subsequently ruled that no girl should remain unmarried after the age of 20, and that no second marriage should take place during the lifetime of the first wife, unless she had no offspring or was afflicted with an incurable disease. These rules apply primarily to Rajputs and Charans, but have been adopted by several other castes. The Walterkrit Sabha meets annually at Ajmer m the spring, when the reports of the local committees are discussed, the year's work examined, and a printed report is published. That for 1905 shows that, in that year, of 4,418 Rajput and Charan marriages reported, the age limits were infringed in only 87 cases and the rule as to expenditure in only 54 cases.

Widow marriage is permitted by all castes except Brahmans, Rajputs, Khattris, Charans, Kayasths, and some of the Mahajan classes. As a rule no Brahmans or priests officiate, and the ceremonies are for the most part restricted to the new husband giving the woman bracelets and clothes and taking her into his house. The custody of the chilaren by the first marriage remains with the deceased husband's family, and the widow forfeits all share in the latter's estate. Among many of the lower castes (for example, the Bhils and Chamars) the widow is expected to marry her late husband's younger brother ; and if she is unwilling to do so, and marries some other man, the latter has to pay compensation to the younger brother.

The rules which in theory govern the custom of polygamy are well known; but in practice, except among the wealthy sections of the community and the Bhil tribes, a second wife is rarely taken unless the first is barren or bears only female chilaren, or suffers from some incurable disease. The custom just referred to, by which the widow contracts a second marriage with her deceased husband's younger brother, leads in many cases to a man having more than one wife, and the Brills usually have two wives. At the Census of 1901 there were in Rajputana, among all religions taken together, 1,046 wives to every 1,000 husbands ; and the statistics show that polygamy is far more common among the Jains, Hindus, and Ammists than among the Musalmans, and that it is most prevalent in the western States. On the other hand, there must have been many married men who were temporarily absent from their homes and had left their wives behind them.