Rakhigarhi

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Excavations

2019: In a first, couple found in Harappan grave

Neha Madaan, In a first, ancient couple found in Harappan grave, January 9, 2019: The Times of India

From: Neha Madaan, In a first, ancient couple found in Harappan grave, January 9, 2019: The Times of India

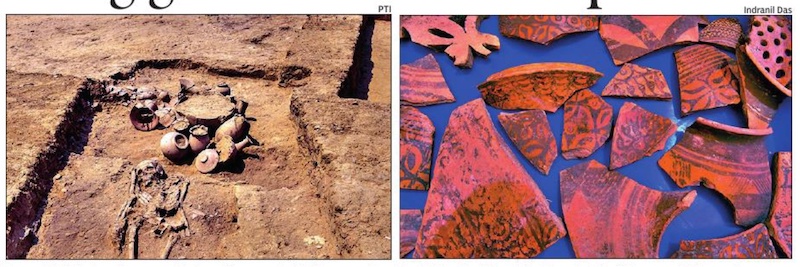

A rare couple’s grave — the skeletal remains of a young man and woman, interred with his face turned towards her — has been excavated at the Harappan settlement at Rakhigarhi in Haryana, about 150km from Delhi. This is the first couple’s grave that archaeologists have confirmed in a Harappan cemetery. Although many Harappan settlements and cemeteries have been investigated, no couple burials have been reported till date.

Archaeologists from Deccan College Deemed University, Pune, who are excavating the site, said the skeletons were found lying face up with arms and legs extended. They said evidence indicated the couple was buried simultaneously or about the same time. The findings were recently published in the peer-reviewed international journal, ACB Journal of Anatomy and Cell Biology.

The excavation and analysis were undertaken by the university’s department of archaeology and Institute of Forensic Science, Seoul National University College of Medicine. Vasant Shinde, one of the authors of the paper, told TOI that Indian archaeologists had often debated the meaning of joint burials. A Harappan joint burial site discovered at Lothal in the past was considered an instance of a widow’s sacrifice following her husband’s death, he said.

HARAPPAN EXCAVATION

‘Both individuals could have died at same time’

Other archaeologists said it was difficult to estimate the sexes of the individuals, and that they may not have been a couple. Other than the contentious Lothal case, none of the joint burials reported from Harappan cemeteries till date have been anthropologically confirmed to be a couple’s grave,” he said.

The manner in which the individuals were buried in the Rakhigarhi site could indicate lasting affection after death. “We can only infer, but those who buried the two individuals may have wanted to imply that the love between the two would continue even

after death,” he said. “A couple’s joint grave is not so rare in other ancient civilisations. Yet, it is strange they were not discovered in Harappan cemeteries till now,” he said.

The grave had burial pottery and a banded agate bead, probably part of a necklace.

Both skeletons were brought to the laboratory of Deccan College for analysis after field surveys were completed. Each skeleton’s sex was determined after studying the pelvic region. Their ages at the time of death has been estimated at between 21 and 35 years and the man’s height as 5 feet 6 inches and the woman’s as 5 feet 2 inches.

“It is more plausible that two individuals died at the same time or almost the same time, and were buried together in the same grave,” Shinde said.

Status in 2020

From: Ajay Sura, Nimesh Khakhariya, Kangkan Kalita, M T Saju & Sandeep Rai, February 24, 2020: The Times of India

In villages across Haryana, heaps of dung cakes drying on farms are a common sight — even on protected land that’s among the largest Indus Valley sites. At Rakhigarhi in Hisar, bullock carts, tractors and cars traverse the ground beneath which remains of an entire civilisation — dating back to 6500 BCE — lie buried. Despite being an Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) site since September 1996, encroachments have grown. The 550 hectares has nine mounds; two are occupied by 200-odd houses and two serve as farmlands. Dung cakes dot the compound of a tiny ASI office.

Wazir Chand Sarohi, 60, who has been working to preserve the site for four decades, said the apathy of authorities was responsible for the present condition. “Villagers were illiterate, not aware of the importance of the site, but wasn’t it the duty of authorities to spread awareness? The delay has caused huge losses to the heritage. But now that the Union government has decided to revive the area and construct an on-site museum, it would change things,” Sarohi told TOI.

Suresh Kumar, a caretaker appointed to protect the area, said things are looking up since the announcement to revamp the area was made. Ashok Khemka, principal secretary, archaeology and museums, Haryana, said the state’s museum is expected to complete within a year.

Zulfiqar Ali, superintending archaeologist, ASI, told TOI that more security personnel are being deployed. But removal of encroachments remains a sticky issue. In 2012, Global Heritage Fund had declared Rakhigarhi one of the 10 most endangered heritage sites in Asia because of encroachments. In 2018, Punjab and Haryana HC ordered removal of illegal houses. But they still stand.

Rakhigarhi sarpanch Rajesh Sheoran said the Centre’s announcement of developing the heritage area was welcome but added that the government would need to first announce a compensation package to rehabilitate residents.

The superintending archaeologist said that land has been identified elsewhere in Rakhigarhi village to shift families. “Houses are being constructed on alternate land where people would be shifted soon.”

2022: Excavations till April

Siddharth Tiwari, May 9, 2022: The Times of India

From: Siddharth Tiwari, May 9, 2022: The Times of India

Rakhigarhi (Hisar): Wide roads, a drainage network, multi-tier houses and possibly ajewellery-making unit — the latest excavation by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) at Rakhigarhi village in Haryana’s Hisar has found enough evidence to suggest that a meticulously planned Harappan city thrived there.

Ateam of 40 archaeologists and research scholars has been excavating three of a total 11 mounds across 350 hectar es in the village. The current round of excavation is likely to conclude by the end of this month. “The ASI and the Haryana government have undertaken this ambitious excavation project and will develop this village as an iconic site to promote the cultural history of the region. The state government is also constructing a museum here,” said Raghavendra Kumar Rai, the assistant director of the archaeology and museums department in Haryana.

“An MoU with the ASI is under way. Once that is done, experts from the ASI and government officials will decide on the modalities. Since this is a prestigious project for both the Centre and the state government, it is expected that the museum should be ready by 2024,” a senior government official said.

Over the past few weeks, ar chaeologists in Rakhigarhi have unearthed evidence of extensive town planning and engineering — straight roads, pucca walls, multi-storeyed houses, drains and even garbage collectors at street corners. “The level of sophistication and the construction of houses and cities is remarka- ble. From carving out streets and lanes to a well-planned drainage system, these reflect advanced engineering that many of our urban centres lack even tod ay,” said a research scholar of the ASI.

A nondescript village in Hisar today, Rakhigarhi first appeared on archeologists' radar in 1998. A three-year-long excavation followed and ASI teams found a cluster of seven mounds that were marked RGR-1 to RGR-7. The second round of excavation began in 2013 and it was speculated that the Rakhigarhi site could well be the largest remnant of the Harappan civilisation. In 2021, the site once again caught the interest of archeologists and four more mounds were discovered — 11 in total — across an area of 350 hectares. Until then, Mohenjo Daro, which spans 300 hectares, was considered to be the largest Harappan city to have been unearthed in the country.

Most of the evidence and artefacts found so far date back to the mature Harappan period, which is nearly 5,000 years old. “We are still excavating and finding pieces of evidence to trace back the cultura l and economic roots of the area. From the broken pottery and metal items, it can be said that there seems to be a conti nuity of the civilisation of the early Harappan period dating back to 7,000 years ago and the mature Harappan period around 2,600 BCE,” ASI director-general Sanjay Kumar Manjul said.

As of now, RGR-1, 3 and 7 are being examined. At RGR-1, a large quantity of waste of semi-precious stones like agate and carnelian, which were used to make objects like beads as part of extensive lapidary, have bee n found. While RGR-1 is said to have a mix of industrial clusters and housing units, RGR-3 possibly had ahousing colony — p ossibly of an aristocratic community — with evidence of street planning, use of burn t brick and a neatly designed drainage system. RGR-7 is said to be the burial ground, where the skeletal remains of two women have been found.

The significance of the findings

Divya A, May 31, 2022: The Indian Express

The latest round of excavations at the 5,000-year-old Harappan site of Rakhigarhi in Haryana’s Hisar has revealed the structure of some houses, lanes and a drainage system, and what could possibly be a jewellery-making unit, say Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) officials leading the project.

A look at these finds and what they mean for our knowledge of the site:

SKELETAL REMAINS: The skeletons of two women were found at Mound No. 7, believed to be nearly 5,000 years old. Pots and other artefacts were found buried next to the remains, part of funerary rituals back, ASI officials said. DNA samples have been sent for tests, whose outcome might provide clues about the ancestry and food habits of people who lived in the region thousands of years ago. The mound had yielded around 60 burials in previous excavations.

S K Manjul, who is leading the excavation team, said the DNA analysis will help answer a lot of questions, anthropological or otherwise. Preliminary scientific tests will be done by the Birbal Sahni Institute of Paleosciences, Lucknow, before the samples being sent elsewhere for further forensic analysis from an anthropological perspective.

SIGNS OF SETTLEMENT: This is the first time excavations have been done on Mound No. 3, which has revealed what appears to be “an aristocratic settlement”; ASI officials said more rounds of excavation will be needed to ascertain its structure and nature. In all Harappan sites excavated so far, there have been similar signs of three tiers of habitation — ‘common settlements’ with mud brick walls, ‘elite settlement’ with burnt brick walls alongside mud brick walls, and possible ‘middle-rung settlements’.

Researchers are yet to determine whether these three levels were based on community or occupation. Clues may surface when excavations resume at Mound No. 3 in September.

ARTEFACTS:Other noteworthy finds include steatite seals, terracotta bangles, terracotta unbaked sealing with relief of elephants, and the Harappan script. Arvin Manjul, Regional Director (North), ASI, said the team also recovered some Harappan sealings (impression of a seal on a surface), indicating that seals were used to mark objects belonging to a set of people or community, as they are today.

She said the 1,000-odd objects recovered this season come from the mature-Harappan period. Archaeologically, the span of the Harappan Civilisation is subdivided into three periods — early (3300 BC to 2600 BC), mature (2600 BC to 1900 BC), and late (1900 BC to 1700 BC). Five urban sites — Mohenjo-Daro, Harappa, Ganweriwala (now in Pakistan), and Rakhigarhi and Dholavira (India) — have been identified as centres of the Civilisation.

JEWELLERY UNIT: A large number of steatite beads, beads of semi-precious stones, shells, and objects made of agate and carnelian have been recovered, said Disha Ahluwalia, a PhD scholar at the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, who is part of the excavation team. The excavation, which has been going on at three of the seven mounds, has also unearthed pieces of copper and gold jewellery.

Possible remains of a 5,000-year-old jewellery making unit have been traced, which signifies that trading was also done from the city, ASI officials said. Manjul said that since there was no quarry of stones like lapis lazuli or shells in the region, the discovery shows extensive trade from areas as far away as Afghanistan, where lapis was found.

Looks: what did the people look like?

Very Caucasoid

Aarti Singh , Oct 10, 2019: The Times of India

From: Aarti Singh , Oct 10, 2019: The Times of India

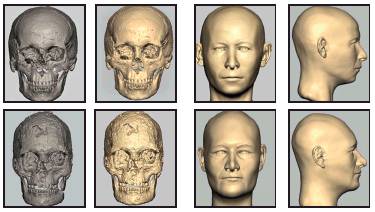

In a first, scientists have generated an accurate facial representation of the Indus Valley Civilisation people by reconstructing the faces of two of the 37 individuals who were found buried at the 4,500-year-old Rakhigarhi cemetry.

A multi-disciplinary team of 15 scientists and academics from six different institutes of South Korea, UK and India, applied craniofacial reconstruction (CFR) technique using computed tomography (CT) data of two of the Rakhigarhi skulls, to recreate their faces. The case study, led by W J Lee and Vasant Shinde and supported in part by a grant of the National Geographic Society, has been published in a widely reputed journal, Anatomical Science International.

“The report is very significant because till date, we have had no idea about how Indus Valley people looked. But now we have got some idea about their facial features,” Shinde, who led the Rakhigarhi archaeological project, told TOI. Located in Haryana, Rakhigarhi is one of the largest Indus Valley sites.

It was difficult to establish the physical appearance so far because “Indus Valley cemeteries and graves have not been investigated sufficiently to date” and “the anthropological data obtained from the skeletons still fall short” for recreating morphology of the Indus Valley people. Also, except for “the Priest King, a famous figurine found at Mohenjodaro,” there is no advanced or developed art from the Indus Valley civilisation that could lead to an accurate representation of the morphology of its population.

“The CFR technology generated faces of the two Rakhigarhi skulls, therefore, is a major breakthrough,” Shinde, a professor at Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute, said. Going by the 3-D video representation of the faces, the two individuals of the Rakhigarhi settlement appeared to have Caucasian features with hawk-shaped and Roman noses. The study, however, cautioned against drawing any generic conclusions.

See also

Rakhigarhi