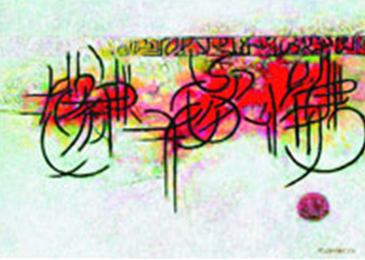

Rashid Arshed, Calligraphy

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Rashid Arshed, Calligraphy

Bold and brilliant

By Salwat Ali

A recent exhibition of Rashid Arshad’s paintings inspired by Islamic Calligraphy at the IVS Gallery in Karachi revives the experimental exuberance that personified the initial years of this art genre

Calligraphy and art have a complex relationship. As sacred text, the genre has a formidable independent status which needs to be re-evaluated when the divine scripture is accessed or appropriated for purely aesthetic concerns. Artists need to distinguish between calligraphy as a sophisticated art of pious writing and the Arabic alphabet as an innovative painterly motif. This distinction then decides the nature of their calligraphic painting.

In Pakistan, experiments with calligraphy began in the early 1950s when stalwarts like Hanif Ramay, Anwer Jalal Shemza, Sadequain and Shakir Ali reinvented the script as an aesthetic exercise. While Shemza opted for unreadable compositions, Hanif Ramay abstracted words without relinquishing the integrity of the message, Sadequain flouted his eloquent penmanship and Shakir Ali evolved a calligraphic form in relation to his basic imagery as a painter. This innovative spirit was kept alive by successive seniors like Zahoor ul Akhlaq, Rashid Arshed, Ismail Gulgee, etc. The genre later enjoyed currency during Zia ul Haq’s era of Islamisation which was marked by prolific production of calligraphic art. But this was abundance sans the conceptual challenge so characteristic of the early years. A recent exhibition of Rashid Arshad’s paintings inspired by Islamic Calligraphy at the IVS Gallery in Karachi, revives the experimental exuberance that personified those initial years.

An artist of the old guard, Rashid Arshed has covered considerable ground in his respective sphere. Graduating from NCA in 1960 he went on to paint abstract figurative compositions of rustic life in Punjab. The proverbial turning point occurred in 1970 when frustrated by an unresolved still life painting he furiously stamped the words Hayat-i- Jamid (still life) on the canvas. He narrates, “The result was no more fascinating yet I felt as if I had been relieved of a heavy burden.”

The written word had established its presence on his canvases. Memories of traditional childhood education of reading the Arabic primer ‘Yasarnul Quran’ and extensive writing on the takhti augmented this new shift in his work. The same year he exhibited his Manuscript series which carried impressions of hand written documents. To stress the message the canvases were titled as preface, page one, two, three, restored relic, epigraph, parchment and footnotes. The artist’s encounter with calligraphy was spontaneous and decisive. He had found his muse and his grasp was intuitive. He approached the genre in terms of form and space or motif and design rather than in terms of words and their meanings and declared that he was “alien to its linguistics and close to its aesthetics.” This creative relationship with the genre was further bolstered when the artist pursued higher education at the Parsons School Of Design, New York, and the School of Visual Arts at Rutgers, the state University of New Jersey. Today an eminent artist of Pakistan, Arshed’s work enjoys wide recognition. His paintings have been displayed in many national and international galleries including the Contemporary Museum of Art in Connecticut, Heckscher Museum in New York, the Art Centre of New Jersey, Jersey City Museum and Indus Gallery and Chawkandi Art in Karachi. Arshed’s work was included in “Pakistan Vision”, an exhibition that toured the UK and was recently part of the 4th Iran Biennial 2006 held in Tehran.

An exhibition, ‘In Letter and Spirit,’ held in Karachi in 2000 is now followed by, ‘In Essence,’ which is yet another series of chromatically vibrant and eclectic works. Rashid Arshed’s singular passion for the beauty of the written word is addressed through multiple design exercises. The artist in him is still challenging the linear rhythms of the script and harnessing them into exciting new spatial designs.

The original manuscript format evolving from the written page is still there but in a myriad other variations. As a modern ‘farman’ stamped with seals, a lined page whose lower half is filled with closely written formal text and a toss up of scripted fragments all painted in his preferred blazing red are delightfully different from each other. The seals, circular discs, exaggerations with the script and multiple stroke variations are old ploys that the artist reinvents in newer forms. Even his palette of reds, blues and blacks and greens is a constant but the combinations keep changing and each work, a singular piece, is yet a continuum of the whole.

Seen in unison, the current paintings can loosely be categorised as active and passive. The quieter minimalist works are sombre in appearance and contemplative in nature. In the others, the activity is violent and aggressive or flamboyant in gesture with bold brilliant colouration and textural stroke work energising the surface.

Two digital paintings, a past present synthesis, evoke the hey-day of the Abstract Expressionists and the current digital craze of hi-tech art. They remind one of Franz Kline and his fascination with Chinese calligraphy. Other oils on canvas of the “In Essence” series have nostalgic overtones extending to the expressionist New York School of the mid 1900’s also. While the younger generation is forward looking the seniors have the added advantage of walking down memory lane and distilling the past to enrich the future. Much can be read in their subjective choices and stylistic treatments. Now that art academics world wide are in a state of flux such works are testimonials to the quality of art education imparted to artists in the previous century and they can provide meaningful comparative analysis with current art forms.

Defying the laws of writing and skilfully dissolving the words into abstract compositions Rashid Arshed paints with the sure handedness of a pro and “In Essence” documents his move towards greater maturity, where less is more.