Rashtrapati Bhavan

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers can send additional information, corrections, photographs and even Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

Overview

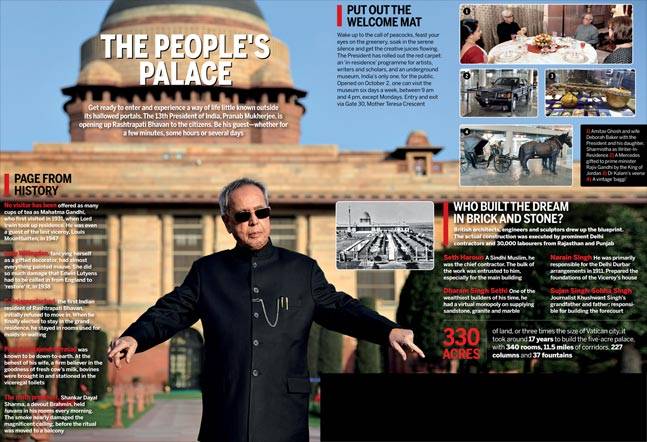

Damayanti Datta , The people’s palace “India Today” 6/10/2016 See graphic

Art

Murals

Sunil Trivedi, April 2, 2022: The Indian Express

From: Sunil Trivedi, April 2, 2022: The Indian Express

From: Sunil Trivedi, April 2, 2022: The Indian Express

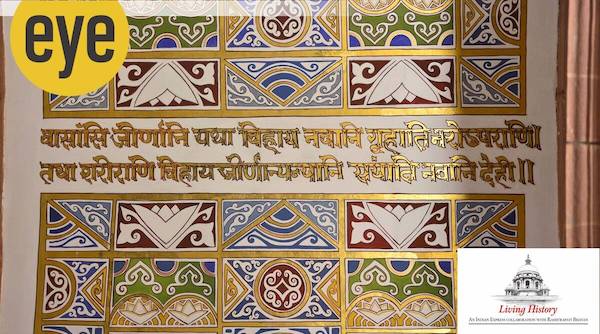

The transformation of the Viceroy’s House into the Rashtrapati Bhavan was a leap from imperialism to nationalism in which the visual art played a major part. The pervasive influence of Swami Vivekananda and Rabindranath Tagore impacted the world of art, too. It swept across the Rashtrapati Bhavan, and as far as the Vatican and the personal collection of the Mountbattens at Broadlands, Hampshire. Paintings of Sukumar Bose, of the Bengal School of art, adorn the walls at the Rashtrapati Bhavan and the house of the Mountbattens. In 1950, Pope Pius XII commissioned Bose, then art curator at the Rashtrapati Bhavan, to create a painting in Indian style on a Christian theme. Titled The Nativity – The Birth of Christ, the painting was at the Vatican and now it appears to be in a private collection.

Margaret Noble, the Irish lady, who became the most famous disciple of Swami Vivekanand and was given the name Sister Nivedita, was a mentor to the early painters of the Bengal School. Well before her demise in 1911, she had anticipated that “mural painting in India will have three different subjects – the national ideals, the national history, and the national life.” Painters from the Bengal School such as Abanindranath Tagore, Asit Kumar Haldar, Lalit Mohan Sen and Bose greatly benefitted from her teachings. Bose created great works of art depicting Indian themes.

A walk through the state corridor of the Rashtrapati Bhavan is evidence of Sister Nivedita’s prescient observations. If one were a visitor of the President, you would be led down the state corridor, a short 75m stretch, before you reach his study. En route, you would see the finest expressions of India’s culture through decorative murals on the vaulted ceilings of the corridor and along its walls.

These murals were painted after independence with a view to indigenise the ambience of the Rashtrapati Bhavan. They are a feast of diverse styles of Indian art, painted in exquisite cohesion. Experts have described this approach to art as an expression of cultural nationalism.

From Harappan seals depicting bulls; motifs from the Thangka style of Tibetan paintings; Buddhist paintings of Ajanta; the alponas of Bengal, and the sacred mandalas that represent the cosmos, figures of lotuses, conch shells, flowers and peacocks have been painted with perfect symmetry and precision. The Indian aesthetics of Satyam-Shivam-Sundaram (Truth, Goodness and Beauty) are reflected in the state corridor, too. As one enters this space, the viewer experiences positive energy and peace all at once. An Indian artist’s dharma is a joyous exploration of truth. That exploration finds fulfilment as one walks along the corridor.

The murals have been done with meditative care. These are highly complex and sophisticated works of art. The once-bare walls and ceilings of the state corridor, running through the North-South axis of the Bhavan, came alive in a celebration of bright colours with these murals. The use of the gold leaf in the paintings adds to the lustre of the motifs. They drench the viewer in shanta rasa, the foundational element of art in India.

Then there are the frescoes, which were selected by the British, for the grand ballroom now, the Ashoka Hall. Beautifully executed, they are about physical might and material excellence. A large painting gifted by the Shah of Iran to the British has been pasted on the ceiling of the Hall, using the marouflage technique. It depicts a hunting expedition of the royal family of Persia. The contrast with the spirituality-imbued murals selected by the Indian presidents is too hard to miss.

One of the striking aspects of the state corridor murals is the 73 shlokas from the Bhagvad Gita, painted in calligraphic style. In his writings, Mahatma Gandhi had personified the Gita as a mother in whose comforting lap he found answers to the most difficult questions of life. Though not a great admirer of the building, the Mahatma would have been very pleased with the prominence given to these verses. Nearly a third of the shlokas have been taken from the 11th Chapter of the Bhagvad Gita, which describes Krishna as the all-pervading cosmic self. The essence of the chapter is that an impersonal and impartial cosmic law sustains the universe, therefore, it is futile to be buffeted by individual impulses. Many shlokas from the second chapter, Sankhya-yoga, have also been depicted through the murals, besides verses from five other chapters. The second chapter contains metaphysics and ethics of the Gita. One shloka reminds one of the story of Janaka, the philosopher-king whose enlightenment enabled him to provide ideal governance to his people. The verse says,

āpūryamāṇ amachalapratiṣhṭhaṁ-

samudramāpaḥ praviśhanti yadvat

tadvatkāmā yaṁ praviśhanti sarve

sa śhāntimāpnoti na kāmakāmī

(Just as the ocean remains undisturbed by the flow of waters merging into it, similarly the wise one who is unmoved despite the flow of desirable objects around him attains peace, and not the person who seeks to satisfy desires.)

This message of equanimity, of adhering to the ultimate truth, of excellence with dispassion is a defining feature of what may be called the first building of the country, the residence and workplace of its first citizen. The main dome of a building can be said to be its head or face. The grand dome of the Rashtrapati Bhavan is an architectural homage to the Sanchi Stupa and the Buddha’s message of compassion and love. The murals in the state corridor are, likewise, a reflection of our philosophy and culture.

Ashoka Emblem in Rasthrapati Bhawan

The Times of India, Oct 28 2015

Himanshi Dhawan

Ashoka emblem finally takes place of British crown at Prez house

To the Presidential palace architecture in 2015 was placing of the Ashoka emblem on the sides of the main gate. “The British had placed two crowns on either side of the gate as a symbol of dominance of the Empire. After Independence the crown was removed but the space atop was left empty. We will now add the Ashoka emblem there, Thomas Mathew, additional secretary to the President, said. The emblem will be made from gunmetal based on a mould taken from the National Museum.

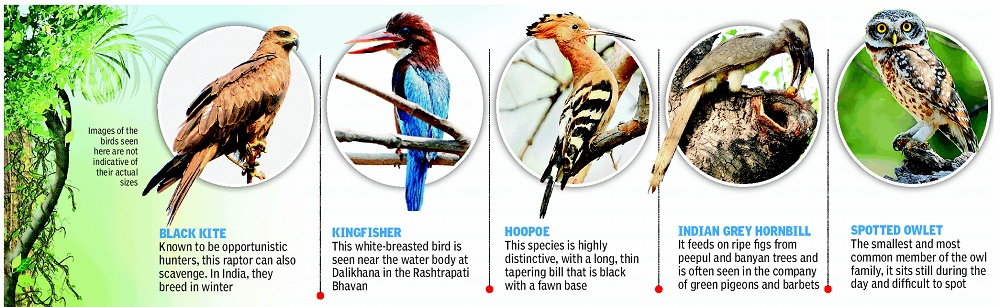

Birds in the Rashtrapati Bhawan

From The Times of India 2013/07/01

Birds in the Rashtrapati Bhawan

Changes, renovations

The Pranab Mukherjee years, 2012-17

Prez Estate gets facelift with Pranab's `smart' touch

The colonial era Rashtrapati Bhavan complex has earned a new sobriquet for itself--4H township. The past few years have seen the humane mesh with hi-tech, heritage married to happiness giving this venerable address a modern face-lift.New residential quarters, a “smart“ connected colony , English speaking courses, health and wellness classes, and perhaps the most important -a green transport service within the vast 330 acre area have all contributed to this change.

A string of initiatives undertaken by outgoing President, Pranab Mukherjee, has transformed the life of the inhabitants. A case in point is the e-rickshaw service within the huge compounds of the presidential estate. For the 6,000-odd residents living on the estate, it's a small step that has brought huge relief. Moving within the vast grounds of the Rashtrapati Bhavan, or even getting outside the estate is tough with no connectivity other than motorised vehicles. The e-rickshaw service introduced some months ago has proved a boon, even for moving between the gates of the presidential estate and the nearest metro station or bus stop. The project, say officials, will have the added benefit of providing employment opportunities to the unemployed residents of the estate.

The efforts started in 2014, with preservation of the existing heritage at the Rashtrapati Bhavan being top of the list, along with introduction of recreational and sports facilities, efficient management of security , water, energy and waste disposal systems, improvement of infrastructure, and creation of new facilities like sewage treatment plant, studio apartments, residential blocks, a ceremonial hall and an AYUSH Wellness Centre.

One of the cornerstones of the improved quality of life at the presidential estate is the introduction of an initiative, codenamed 4S. It's four components are: Sanskar, a project for pre-school children; Sparsh, which is designed for specially-abled children; Sanskriti, for children in the 7-14 years' age group and Samaga, targeting senior citizens living in the estate.

That the initiatives found approval from residents was acknowledged by Mukherjee last year, when he himself coined the term “4H“ for the presidential estate. While inau gurating an intelligent operations centre for a `smart' president's estate on May 19, 2016, Mukherjee quipped, “If I were to use a word to describe a human emotion associated with this on-going transformation of quality of life in the township, it will be happiness...Today , recognizing the smiles on the faces of my people, I will like to add one more `H' to our model of 3H, and that is `Happiness'. The smart President's Estate is now a 4H Estate Humane, Hi-tech, Heritage and Happy .“

It's one of the most extensive projects for improvement of quality of life at the Rashtrapati Bhavan complex, with the past five years witnessing large-scale projects within the estate. It wasn't just addition of more residential quarters but also the attention on holistic improvement, through projects like the 4S initiative, modernisation of the Dr Rajendra Prasad Sarvodaya Vidyalaya in the estate.

The Ram Nath Kovind years, 2017-..

At Home on 26 Jan

2018: President reduces guest list from 2,000+ to 724

Rumu Banerjee, Prez prunes At-Home guest list to 724 from 2k, January 29, 2018: The Times of India

This Republic Day, it wasn’t the usual ‘At Home’ in Rashtrapati Bhavan. Unlike previous years, the event saw a more intimate gathering, with President Ram Nath Kovind pruning the guest list from 2,000 to 724.

It wasn’t just the guest list that was different. Sources said ‘achievers’ were invited. Like Milind Kamble, an entrepreneur who established the Dalit Chamber of Commerce and Industry (DICCI), as well as Under-17 football captain Amarjit Singh from Manipur. The family of IAF commando Corporal Jyoti Prakash Nirala, who was awarded the Ashok Chakra posthumously at the Republic Day function in the morning, was also received by the President at the ‘At Home’.

Others making it to the guest list included ‘young achievers’ like toppers of CBSE, ISC and UPSC exams along with the Phogat sisters. “Inviting the four young girls from Haryana, who are medal winners, was a powerful message,” said a source involved with the process.

The other message was also clear: broadbase the list, move away from Lutyens zone and south Delhi, a source said. “The President made it a point not to invite even his immediate family. Only the First Lady was present at the event,” the source added.

The list, however, had the mandatory invitees, such as Members of Parliament, former chief justices, heads of the defence forces, high commissioners and ambassadors as well as constitutional figures.

Press secretary to the President Ashok Malik said, “This year, the guest list had 724 names. In previous years, the list was three times longer.” According to sources, the reason for the cropped list was Kovind’s desire for a more exclusive gathering, without the crush of a large number of guests. In previous years, the long list — which had 2,347 names in 2016 and 2,015 in 2017 — had led to separate enclosures for the more “important” guests, as well as measures like keeping cell phones away from the event. This year, sources said, mobile phones were allowed, with guests not being subjected to the intense frisking that was the norm earlier.

The Guest Suite

The Hindu, February 28, 2016

“I shall be happy to stay with you while in Delhi,” reads the telegram, which, in ordinary course, should mean little more than a customary acceptance of an invitation of hospitality. But this is a piece of precious history: a handwritten note dated March 1950 sent by the Prime Minister of Pakistan Liaquat Ali Khan to President Dr. Rajendra Prasad, not two years after the deadly riots of Partition that left about a million Indians and Pakistanis dead.

The ‘stay’ it speaks of is at the 29-room, three-storey ‘guest wing’ or north-west wing of Rashtrapati Bhavan, where Heads of State and government officials stayed for decades after India’s independence. The practice of hosting foreign dignitaries waned during the 1970s and the guest wing saw few visitors until a large-scale renovation brought them back in 2014. Each visit — and there were 52 by 32 world leaders between 1947 and 1967 — has been painstakingly documented with photographs in a new volume called Abode Under the Dome, recently released by Rashtrapati Bhavan.

While the pomp and protocol of the Indian presidential palace has been written about in the past, rarely have the visits by leaders of the two countries that India has been to war with been so elaborately detailed. As a result, six visits by Pakistan’s Presidents and Prime Ministers and four visits by Chinese Premier Chou En-Lai make for astonishing reading and for an insightful window into the 1950s.

Take, for example, the tour programme for Pakistani leaders. It was customary for Nehru to greet each one of them at the airport, and masses of crowds to throng the way cheering the visiting leader, regardless of the obvious animosity and tension between the two newly cleaved countries. When Pakistan Prime Minister Mohammad Ali Bogra landed on August 16, 1953, a congregation of 20,000 gathered at Palam airport, and proved difficult to control. Realising the police personnel’s problem, Prime Ministers Nehru and Bogra and Mrs. Bogra got into an open jeep rather than their limousine, and drove past the crowds waving on their way to Rashtrapati Bhavan.

Pakistani premiers would get the 21-gun salute on their departure and, according to the daily agendas set out in the book, spent practically every waking hour in meetings with Nehru, Rajendra Prasad, the then President, in attending formal banquets at Rashtrapati Bhavan and cultural performances at the National Stadium together.

Another stop on every Pakistani leader’s tour was to see the condition of refugees who had fled the violence in Pakistan during Partition. In January 1955, when Governor-General (the earlier term for the Pakistani President) Malik Ghulam Mohammed arrived as the chief guest of the Republic Day parade, he brought with him Dr. Khan Sahib. Dr. Khan Sahib (Abdul Jabbar Khan, the Chief Minister of the North-West Frontier Provinces until 1947) and his brother, the ‘Frontier Gandhi’ Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan were popular in India, with many refugees crediting their lives to their efforts at having helped them escape the violence (Khan Market and Ghaffar Market in Delhi were named after them). The cavalcade on that visit was thronged by crowds.

Another interesting story not covered in the book for reasons that will be revealed is that of the two visits of Bogra: in August 1953 and May 1955. On both occasions, he was accompanied by a different wife, as the photographs show, but the text doesn’t refer to it. Mohammad Ali Bogra was a colourful character, a bow tie-wearing bon vivant through his days as Pakistan’s Ambassador to the U.S. from where he was brought to replace Khwaja Nazimuddin, the premier who had been summarily dismissed.

Mr. Bogra brought back from Washington his Lebanese stenographer, Aliya, who he married after becoming premier. But while a second marriage was legal in Pakistan, it was considered a no-no in high society, particularly since his wife Begum Hameeda made her displeasure known. This started a “social boycott” of all functions where Begum Aliya was brought and of all her public engagements, as recorded by author Rafia Zakaria in her book, The Upstairs Wife: An Intimate History of Pakistan.

As a result, the visit to India was a welcome break from the stern silences that Begum Aliya suffered in Karachi society (then still the Pakistani capital), and the photographs show her smiling and chatting with Rajendra Prasad and others. Not three months later, however, Bogra too had to resign, one of a string of Prime Ministers manipulated by Pakistan’s military generals, who frequently imposed martial law during that time even as they plotted war with India.

While Pakistan’s leadership faced turbulence, China’s didn’t change through the 1950s, and Premier Chou En-Lai made as many as four visits — in 1954, 1956, 1957 and 1960 — his last visit, not two years before the India-China war, left a lasting scar on relations.

Some of those tensions were visible even then, according to the records of his last visit. He held a combative press conference inside Rashtrapati Bhavan that lasted over two hours, where he called for India to show flexibility on the Western sector (Ladakh) in exchange for Chinese flexibility on the Eastern sector (Arunachal Pradesh). In Parliament the next day, Nehru said flatly, “This is not some barter.” There was another reason for the tensions at the time. In 1959, the Dalai Lama had sought and received asylum in India. Interestingly, just a few years before that, Chou En Lai had met the Dalai Lama at Rashtrapati Bhavan, when both had been on a visit to India at the same time.

This strain contrasted with Chou’s first visit in 1954, when the welcome he received was nothing short of effusive. Much like Narendra Modi’s recent Lahore visit, Chou’s first visit to Delhi was kept a secret until he was about to land. India even sent its own plane (a four-engine Air India International Constellation, the ‘Maratha Princess’) to Geneva, to pick up Chou En Lai and bring him to Delhi. Thousands or people greeted Chou at various places, including at the refugee camps, and hundreds attended his dinner reception at Rashtrapati Bhavan. Unlike 1960, Chou and Nehru addressed a joint press conference, answering dozens of (pre-screened) questions from the media together. When he left India, he had a surprise organised by Nehru on the flight. The Air India staff served him the best mangoes of the season on board the flight to Beijing (then Peking), which Chou famously called a “taste of paradise”. The focus on food was to remain. When he returned in 1956, an MEA advisory told Rashtrapati Bhavan staff about his preference for “Crabs, Lobsters, Oysters, Prawns, Sea Slugs etc.” and Chinese, not Indian tea.

Under the Dome brings these and many other interesting anecdotes to light, along with photographs that have been chosen from an in-house collection of tens of thousands of official photos. According to author Thomas Mathew, at least 3,000 days of newspapers were scanned in order to give the political context to incidents that had been recorded mainly through letters received from the leaders, tour programmes, menus, and housekeeping instructions

Mughal Gardens

A backgrounder

January 30, 2023: The Indian Express

A long history of Mughal Gardens in India

The Mughals were known to appreciate gardens. In Babur Nama, Babur says that his favourite kind of garden is the Persian charbagh style (literally, four gardens). The charbagh structure was intended to create a representation of an earthly utopia – jannat – in which humans co-exist in perfect harmony with all elements of nature.

Defined by its rectilinear layouts, divided in four equal sections, these gardens can be found across lands previously ruled by the Mughals. From the gardens surrounding Humanyun’s Tomb in Delhi to the Nishat Bagh in Srinagar, all are built in this style – giving them the moniker of Mughal Gardens.

A defining feature of these gardens is the use of waterways, often to demarcate the various quadrants of the garden. These were not only crucial to maintain the flora of the garden, they also were an important part of its aesthetic. Fountains were often built, symbolising the “cycle of life.”

The gardens at the new Viceroy’s house

In 1911, the British decided to shift the Indian capital from Calcutta to Delhi. This would be a mammoth exercise, involving the construction of a whole new city – New Delhi – that would be built as the British Crown’s seat of power in its most valuable colony.

About 4,000 acres of land was acquired to construct the Viceroy’s House with Sir Edwin Lutyens being given the task of designing the building on Raisina Hill. Lutyens’ designs combined elements of classical European architecture with Indian styles, producing a unique aesthetic that defines Lutyens’ Delhi till date.

Crucial in the design of the Viceroy’s House was a large garden in its rear. While initial plans involved creating a garden with traditional British sensibilities in mind, Lady Hardinge, the wife of the then Viceroy, urged planners to create a Mughal-style garden. It is said that she was inspired by the book Gardens of the Great Mughals (1913) by Constance Villiers-Stuart as well as her visits to the Mughal gardens in Lahore and Srinagar.

The famous roses of the garden

Though the layout of the garden was in place by 1917, the planting was taken up only in 1928-29. Director of horticulture William Mustoe, who planted the garden, was especially skilled at growing roses and is said to have introduced more than 250 different varieties of hybrid roses gathered from every corner of the world. Lady Beatrix Stanley, a prominent horticulturist, noted in 1931 that she had not seen better roses in England. Later, more variety was added, especially during the presidency of Dr Zakir Husain.

The gardeners of the Rashtrapati Bhavan have kept alive the tradition of nurturing the defining feature of the gardens — the multitude of rose varieties. They include Adora, Mrinalini, Taj Mahal, Eiffel Tower, Scentimental, Oklahoma (also called Black Rose), Black Lady, Blue Moon and Lady X. There are also roses named after personalities: Mother Teresa, Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Abraham Lincoln, Jawahar Lal Nehru, and Queen Elizabeth — not to forget Arjun and Bhim. The ingenious gardeners also introduced new, exotic varieties of flowers like birds of paradise, tulips and heliconia in 1998.

Each resident of the Rashtrapati Bhavan leaves their own touch

The gardens have evolved over time. While roses remain the star attraction, residents of the Rashtrapati Bhavan have all added their own personal touch to the garden.

For instance, C Rajagopalachari, the last Governor General of India, made a political statement when during a period of food shortage in the country, he himself ploughed the lands and dedicated a section of the garden to foodgrains. Today, the Nutrition Garden, popularly known as Dalikhana, stands in that spot, organically cultivating a variety of vegetables for consumption at the Rashtrapati Bhavan.

President R Venkatraman added a cactus garden (he just liked cacti) and APJ Abdul Kalam added many theme-based gardens: from the musical garden to the spiritual garden.

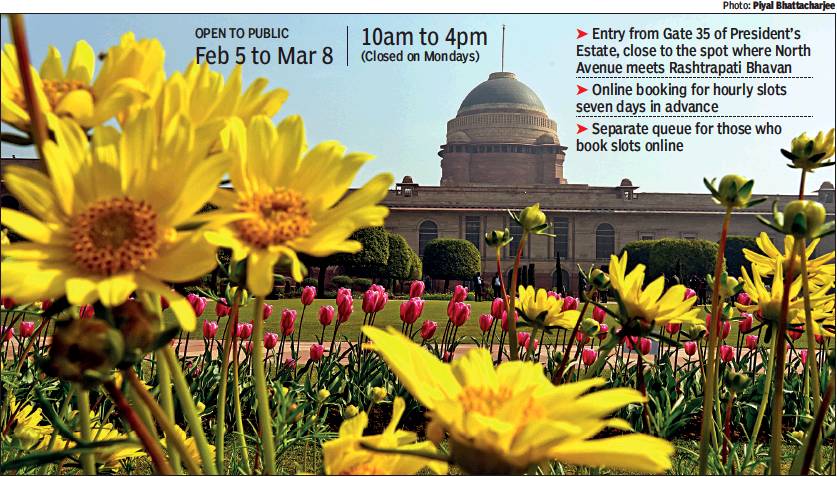

Annual spring festival: 2020

From: All the President’s men keep tradition alive, Chandrima Banerjee, February 3, 2020: The Times of India

Mornings were especially tough on Vimla in the cold wave that gripped Delhi this December. But by 7am every day, the 50-yearold would be at work, removing weeds around the ‘sherbet’ roses of the Mughal Gardens at Rashtrapati Bhavan. “It was a difficult winter,” she said, but she had to make sure the flowers endured.

Every February, just as the biting cold begins to yield, the Mughal Gardens open to the public as part of ‘Udyanotsav’. Putting it together this year, the garden staff said, was the most difficult it has ever been. The day before 2019 ended was Delhi’s coldest in 119 years. For weeks around that time, the weather was the city’s only relevant subject of conversation. “But we had to prepare. Opening of the gardens is an unbroken tradition. We covered the stalks with plastic and placed nets on the shrubs to prevent frost,” said Ramesh Sharma, a 53-year-old senior gardener on the grounds.

The 42 garden staff members of the presidential residence did keep the tradition alive. The gardens open on February 5. The numbers are big — 15 acres, 138 varieties of roses, 5,000 dahlias, 10,000 tulips. The names are quirky — ‘Mother Teresa’ is a chrysanthemum and ‘Red Pinocchio’ is a rose, as is ‘Delhi Princess’. A pale yellow-orange rose is ‘President Pranab’. The American connect is strong and many rose shrubs are named after holidays — ‘Memorial Day’, ‘Fourth of July’ — or states like ‘Oklahoma’, ‘Pasadena’, ‘Louisiana’. “But that’s just the rose federation,” said PN Joshi, superintendent of the President’s gardens, referring to the World Federation of Rose Societies.

Names have often sparked strange controversies. In 2014, a rose named ‘Sonia’ stirred a hornet’s nest. That it was named not after the Congress politician but a rose cultivator from France didn’t seem to matter much. The perceived symbolism did. A rose by any other name would, perhaps, have placated those who were incensed. Then, last December, a fringe outfit wanted the entire garden to be renamed. The demand was oblivious to history — that the charbagh Mughal gardens of Kashmir and the pleasure gardens of Europe had inspired Edward Lutyens, who designed this one over seven years. “When (APJ Abdul) Kalam ji was President, he said he wanted a spiritual garden. Plants and trees significant to each religion — tulsi, henna, dates — were grown together in the garden as a symbol of unity. It’s important to see the world like that,” Joshi said.

Rashtrapati Bhavan had seven occupants in the 33 years Joshi has been around, tending to the gardens. Each President has brought something new — under Shankar Dayal Sharma, the garden went organic; KR Narayanan introduced a rainwater catchment system and Kalam brought in a herb garden with indigenous plants.

Earlier, the first Indian resident of the Rashtrapati Bhavan and the first governor general of independent India, C Rajagopalachari, had subverted the opulence of the gardens at a time when the country was facing a food crisis and sectioned off an area for wheat cultivation. “The practice continued till 1962, under our first President Rajendra Prasad. There’s a lot to the history of this place,” said Kumar Samresh, public relations officer of the President’s secretariat.

Stationery

Seedy stationery/ 2019

Swati Mathur, Rashtrapati Bhavan invitations to bloom now, April 14, 2019: The Times of India

If you happen to be on the President of India’s guest list for the next function he hosts at the Rashtrapati Bhavan, hang on to that monogrammed paper invite you received. You can plant it and watch it bloom into a marigold.

In continuation of the many green initiatives undertaken since President Ram Nath Kovind assumed office, the Rashtrapati Bhavan has decided to switch to using seed paper, a type of handmade paper that has seeds embedded in it, and which can germinate if planted under a thin layer of soil and watered, adequately. The first batch of seed paper invites has been readied and the next event that President Kovind hosts, sources said, will be sent out on this format.

In order to accomplish this green mission, to begin with Rashtrapati Bhavan commissioned an external agency to recycle nearly 1,700 kilos of waste paper and convert it into seed paper.

After a toss up between embedding tomato or marigold seeds, the Rashtrapati Bhavan chose marigold seeds. In addition to producing seed paper from waste, the recycling project is also exploring the options of producing pencils, pen stands and stationary.