Rautia, Chota Nagpur

Contents |

Rautia, Chota Nagpur

This section has been extracted from THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all posts in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

Origin

A landholding and cultivating caste of Chota Nagpur, probably Dravidian in its original affinities, but since refned meanres an comp enon by a large infusion of Aryan blood. The name Rautia suggests some connexion with Haj puts, and Mr. Beames has noticed that the cognate term Raut is used in some districts to denote an inferior Hajput, "the corruption of the name betokening the corruption of the caste."l Their traditions say that they formerly dwelled in Sinhal-dwip (Oeylon), whence they migrated to Barhar, in Mirzapur. In the time of the Emperor Jahangir' some Rautias were serving as sentinels in the fort at Gwalior when Maharaja DUljan Sah of Ohutia N agpur was imprisoned there for failure to pay his tribute to Dehli.2 Dllriog his confinement the Hautias treated the Raja kindly, and he repaid their good offices on his release by giving them lands in pargana Panari of Lohardaga. Further grants of villages, groups of vilJaO'es, and entire parganas were afterwards made to them in jagir, ~nd many of these are in existence at the present day. The titles of Baraik, Gaunjhu, and Kotwar were at the same time conferred upon them.

Internal structure

, The Ratias are divided into two endogamous sub-castes-Bargohri and Chhot-gohri. The origin of this division is obscure. The Rautias them-selves tell an absurd story to account for it. They say that the Bar-gohris were the first to arrive in their present habitat. When the Chhot-gohris came they were asled with what cooking pots and on what fire-places they had cooked their food after the Bar-gobris had started. On their replying that they had used the pots and fire-places left behind by the Bar-gohris, hut had cleaned them, the latter straightway took offence, and from that time forth have refused to eat cooked food (kachi) with the Ohhot-gohri. Following the analogy of similar schisms in castes formerly united, it seeOlS more likely either that the Chhot-gohri were the first settlers and were outcasted for some such breach of caste rules as people are apt to commit, or to be taxed with committing, when they settle in outlandish parts of the country, or that the Chhot-goill'i are the offspring of alliances between the Bar-gohri and women of inferiur caste or purity of lineage. At the present day the Chhot-gohri eat fowls and wild pig and drink spirits, all of which things are forbidden for members of the higher group.

Within each sub-caste we find a group called Berra Rautia, who are admittedly descendants of Rautias by concubines of other castes. Although lJot strictly endogamous, the Berras observe certain special restrictions in the matter of marriage. Thus a Berra whose mother was a Rajput will not marry a gil'l whose mother was a Ghasi.

Both sub-castes have a long list of sections (pa1'is or got), which will be found in the Appendix. The fact that the list contaius totemistic, eponymous, and territorial names, tells on the whole in favom of the view that the Rautias are people of mixed descent. The rule that the totem is taboo to its bearers seems only to apply to the animal-totems, which may be named, but not killed or eaten; for a Rautia of the sword or axe groups is not forbidden to use those weapons, nor is a man of the Kasi group forbidden to touoh the

grass from wbich his section is supposed to be desoended.

The seotion name goes by the male side, and the pl'ohibition attaohed to it affeots only a man's own section and does not pl'event him from marrying a woman belonging to the same seotion as his mother. 'rhis simple l'ule of exogamy is therefOl'e supplemented by a table of prohibited degl'ees made up, like OUT own, by enumerating the individual relatives whom a man may not many, and not, as is more usual, by pl'ohibiting intermarriage with oertaiu large classes of l'elations or with the descendants within certain degrees of particular relations.

Marriages

Girls are married either as infants or adults, usually between the ages of eight and eighteen. Sexual license before maniage is not openly recognized, as it is among the aborigines of Chota Nagpur; but I am informed that grown-up girls enjoy considerable liberty in this respect, it being understood that in case of pregnancy a husband will be at once forthcoming. In theory polygamy is allowed without any restriction being laid on the number of wives or any antecedent condition being insisted on, such as that the first wife must be barren or be iuflicted with an incurable disease in order to entitle her husband to take another wife. In actual life, however, it is unusual to find a man with more than three or four wives. One simple reason for this is that few men oan afford to keep many wives or have house-room to accommodate them, as by universal custom each wife must have a separate room. A widow is allowed to marry again by the sagai form, and it is considered right for her to marry her late husband's younger brother. Under no circumstances can she marry the elder brother. If she marries an outsider, her late husband's brother, father, or uncle have the right to the custody of all her children, both male and female. In any case she aoquires no rights in her late husband's property, the whole of whioh passes to his eldest son, subjeot to certain obligations to provide, by way of main¬tenance, for younger brothers. If a widow marries her late husband's younger brother, her children by him are not deemed the children of her first husband, nor have they any rights in respect of his property.

The ritual used at the marriage of a widow is very simple. Five married women whose husbands are living take a s(l1'i, a pair of lac bracelets, and a little vermilion (sindu1') to the bridegroom and get him to touoh eaoh article. They then return to the bride, attire her in the S(i1-i and bracelets, and daub the vermilion on her forehead. As in the case of a regular marriage, the prooeedings conclude with a feast to the friends and relatives of the newly¬married couple.

A woman may be divorced for adultery or for eating with a member of another caste. For lighter offenoes than these, separation is the only punishment awarded j and in that case the husband is bound to maintain his wife. A divorced woman may not marry again. If she lives with a man, she ranks as a concubine and her children are illegitimate.

The oeremony performed at the marriage of a virgin

bride contains several features of a primitive and non-Aryan

character. In the first instanoe, both parties go through the

form of marriage to a mango tree (amM bilui). The essential

and binding portions of the ritual are the knotting together

of the clothes of the bride and bridegroom and sindw'dal1,

which is effected by smearing on the bride's forehead a drop of

blood drawn from the little finger of the bridegroom, and vice

versa, Sakadwipi Brahmans officiate, and offerings are made to

Gauri and Ganesa.

Ma~ages are arranged by the parents or guardians of the

parties, who have no freedom of choice in the matter. Professional

marriage-brokers are unknown. The first offer is made by the father

of the bridegroom, and a bride-price (dati taka), varying according

to the means of the bridegroom's parents, is paid to the parents of

the bride, by whom it is retained. No portion of the bride-price

becomes the special property of the bride.

Succession

The Mitakshani commentary, which forms the personal law of most Hindus in Lohardaga, does not apply to Rautias, who are governed by special customs of their own. The eldest son by a regularly-married (biluii) wife inherits the whole of his father's property, subject to the obligation of creating maintenance grants in favour of his younger brothers. These grants are not equal in value, but are supposed to decrease in the order of age of the grantees, so that each younger brother gets a smaller grant than his immediate elder, and so on. Instance!'!, however, have occurred among the Bar-gohri Rautias in which, with the consent of the eldest son, an entire property has been equally divided. Sons by a sagai wue are included in this arrangement, but get smaller grants than sons by a biluii wife. The rule that sons by a biluii wife take precedence of sons by a sagai wife is subject to the important exception that an elder brother's widow, though married by the sagai form, ranks in all respects as a biluii wife, and her sons have the full rights of succession to their father. This principle was affirmed by the Civil Courts in a case which occurred a few years ago. One of the Rautii Baraiks of Basia died leaving a widow and infant son j the widow married in the sogai form her late husband's younger brother, who was already married to a biMi wife. Both of the wives bore sons, the sagai wife a few months earlier than the biMi wife. Meanwhile the infant son of the original proprietor died: the whole property passed.. to his brother, and on his death was disputed between his sons. It was held that the son of the sagai wife, being the eldest, was entitled to succeed under the custom of the caste, and that the son of the bi/uii wife had only a right to maintenance.

It will be seen from this instance that a brother excludes a widow from succession. The latter is in fact entitled only to maintenance, and may forfeit even that by misconduct or infringement of casie rules. Brothers and uncles, or their descendants, exclude daughters and their descendants. Succession indeed is strictly agnatio throughout j the eldest male of the eldest line taking the entire inheritance subject to the obligation to provide maintenance for relatives within certain degrees on a scale progressively diminishing i,n relation to the age and propinquity

in relationship of the claimants. '1'he distinction between ancestral and self-acquired property, which has acquired such prominence in the standard Hindu law, does not seem to be very clearly recognized in the customary law of the Rautias. I gather, however, that such property is not subject to the rule of primogeniture, but is ordinarily divided equally among the male descendants.

Step-sons are not entitled to maintenance from the estate of their step-father. Owing, however, to the fact that a widow may marry her late husband's younger brother and may not marry his eldest brother, it happens that a large proportion of the step-sons among the Rautias are really the heirs to the estates of which their step-fathers happen for the time being to be in charge. A ghd?' djjwi, or son-in-law who lives with his wife in his father-in-Iaw's household, retains his claims on his natural father's property, but aoquires no right to ~ maintenance grant from his father-in-law's estate.

Adoption is unknown-a circumstance from which we may either infer that the Rautias are free from the curse of childlessness, so common in the higher ranks of Hindus, or that one of the inducements to adopt sons has been removed by the rule regarding land referred to in the next paragraph.

In the event of a Rautia. dying without male heirs, his immov¬able property reverts to his superior landlord or the legal represen¬tative of the person by whom the land was originally granted. In suoh cases the landlord is expected to make some small provision for the maintenance of the females of the family. His movable property goes to the person who performs his funeral rites.

An elder brother can transfer to a younger brother all his rights in the family property, but the effect of such a transfer is limited to his own lifetime, and does not ourtail the rights of his son, who will succeed, in preference to the uncle on attaining his majority.

Religion

The religion of the Rautias may best be described• as a mixture of the primitive animism characteristic of the aboriginal races and the debased form of Hinduism which has been disseminated in chota N agpur by a class of Brahmans markedly inferior in point of learning and ceremonial purity to those who stand forth as the representatives or the caste in the great centres of Hindu civilization. Among the Bar-gohri Rautias many have of late years beoome Kabirpanthis; the rest, with most of the Ohhot-gohri and the Berras o~ both sub• castes, are Ramayat Vaishnavas. A few only have adopted the tenets or tho Saiva sects. Rama, Ganesa, Mahadeva, and Gauri are the favourite deities, whose worship is conducted by Sakadwipi Brahmans more or Ie s in the orthodox fashion. Behind the fairly definite personalities of these greator gods there loom in tho background, through a fog of ignorance and superstition, the dim shapes of Bar-pabar (the Marang Bul'll or mountain of the Mundas); Bura-buri, the supposed ancestors of mankind; the seven sisters who scatter cholera, small-pox, and cattle• plague abroad; Goraia, the village god-a sort of rural Terminus; and the myriad demons with which the imagination of the KoThs peoples the trees, rooks, streams, and fields of its surroundings.

To BarpaMr are offered he-buffaloes, rams, he-goats, fowls,

milk, flowers, and sweetmeats ; the animals in each case being given

some rice to chew and decked with garlands of flowers before being

sacrificed. When offered in pursuance of a special vow, the animal is

called c/zal'(iol, and is slain in the early morning in the sa1'nrl or

sacred grove outside the village; rice, ghi, molasses, vermilion, flowers,

and bet leaves being presented at the same time. No female may

be present at the ceremony. The carcase of the victim is distributed

among the worshippers, but no part of it may be taken into the village,

and it is cooked and eaten on the spot, even the remnants heing

buried in the Sania at the end of the feast. The head is eaten by

the man who made the vow and the members of his family, but no

others share in it, owing to the belief that whoever partakes of the

head would thereby render himself liable to perform a similar puja.

When a buffalo is sacrificed, the Rautilis do not eat the flesh them¬

selves, but leave the carcase to the Mundas, Rharias, and other beef¬

eating-folk who may happen to be present.

To the seven sisters (devis) and their brother Bhairo a rude shrine (devigarhi) is erected in the centre of every village, consisting of a raised plinth five cubits square covered by a tiled or thatched roof resting on six posts of {lulaichi trees (Plume1•ia). In the middle of the plinth, on a line running north and south, stand seven little mounds of dried mud, representing the seven god¬ desses, while a smaller mound on one side stands for Bhairo. In front of the Devigal'hi, at some ten or fifteen cubits distance, is a larger mound representing Goraiya, the village god, to whom pigs are sacrificed by the village priest (pahan) and by men of the Dosadh caste. Regarding the lIames and functions of the seven sisters there seems to be much uncertainty. Some Rautias enumerate the following ;- Burhia Mai or Sitala. Kankarin Mai. Kali Mai. Kuleswari MaL B.igheswari Mai. Mareswari Mai. Dulhari Mai. Others substitute Jwala.-mukhi, Vindhyabasini, MaIat Mai, and Joginia M.ii for the last four. J wala-mukhi is a place of pilgrimage in the Lower Himalayas north of the Panjab, where inflammable gas issues from the ground and is believed to be the fire created by Parbati when she desired to become a sati. Vindhyabasini is a common title of Sitala Devi, who presides over small-pox throughout Northern India. I cannot find out which sisters are supposed to be responsible for cholera and cattle-plague. Kuleshwari (kul = 'tiger' in Mundari) and Bagheswari apparently haye to do with the tiger. He-goats, flowers, fruit, and bel leaves are offered to the seven sisters in front of the devi-gtwhi. Women and children are present at the worship. A Sakadwipi Brahman presides, but does not slay the victims. The following are the festivals observed by the Rautia.s ;¬ (1) Nawa Khani-eating new rice with milk, molasses. and F t' 1 ghi. On the 12th of the light half of BMdon as iva s. (middle of September) and the 15th of the light half of Aghan (middle of November). These periods correspond respectively to the harvesting of the low land and high land rice crops. (2) Jitia parab.-On the 8th of the dark half of Rsin (end of. Septemb~r). The females of the village, after fasting a day, brIng a tWIg from aJitia pipat tree (Ficus 1'e/'igiosa) and an ear of rice, and plant them in the courtyard of a house, usually that of the chief man of the village. Vermilion, arU'a or rice husked without boiling, flowers, and sweetmeats, are offered to the twig. Dancing, singing, and processions of various kinds follow, and in the morning, nfter watching the twigs all night, the women offer manto or rice gruel to their deceased anoestors. (3) Dasahara-corre!'ponding to the Devi-puja and Vijaya dasmi of t.he Hindus.-On the loth of the light half of Ksin (early in October). (4) Debathan-a fast, followed by eating various kinds of boiled fruit and roots-observed only by bachelors and spinsters on the eleventh of the lighthali of Kartik (middle of November). (5) Ganesh Chauth.-On the 4th of the dark hali of Magh (middle of January). An image of Ganesa is made out of cow-dung and is worshipped with laddus or cakes of til, legends being recited at the same time. (6) Phagua-corresponding to the Holi of the Hindus.-On the 15th of the light half of l:'h8.gun (middle of March), when ancestors are propitiated. (7) Karma.-On the lIth of the light half of Bh8.don (begin¬ning of September). This festival is similar to the Jitia, exoept that a branoh of a karam tree (Nauclea cordi/olia) is planted in the court¬yard and the fasting is not continuous as in the Jitiya Parab.

The foregoing festivals are observed by all Rautias. The more Hinduised members of the caste add to them the Rath-jatra, the J anmashtami, the Ramnabami, and the Ind Parab.

Disposal of tho dead

The dead are usually disposed of by burning, except in the case of Kabirpanthi Rautias, who are buried standing upright and facing to the north. In the former case the corpse, covered with a new clotb, is taken to the place of oremation (masan) and there shaved, bathed, and clotbed in a new waistcloth and sheet. If the body be that of a woman whose husband is alive, it is bathed, anointed with oil, and dre sed in a new sari. In the case of a widow the oiling is omitted. The corpse is tben placed ou the funeral pile with the head to the north, and the ohief mourner, lighting a torch made of five dry twigs of a bel tree tied to the end of a bit of wood and soaked in ghi, walks round the pile seven times, applies the toroh to the mouth of the deceased, and then sets fire to the pile. Before doing so however, he takes a portion of the sheet in which the corpse is dressed and wraps up in it a knife or a piece of iron. This piece of cloth must be kept for ten days. Alter the body bas been consumed, the ashes are colleoted in a new earthen vessel (ghtinti). On returning home the mourners wash their feet with water previously placed for tbem out ide the house.

Inside the courtyard a shallow brass dish (tluili) is laid ready with leaves of the tulsi (Oc.llmum sanctum) and kareli (Mom01'dica chal'ontia), one pice, and a vessel of water. Some person, not a member of the family, pours a little water into the hand of each mourner, who drinks it off. For ten days after the oremation the ashes of the deceased (sallth) are hung up in the ve sel in which they were placed. During this time the chief mourner must make daily libations to the asbes, and must keep on his person the piece of sheet and the iron aheady referred to. He may not cbange his clothes, sleep on a bed, or eat salt, and he oan only take one meal a day,

which he musL cook himself. At the end of this time the ashes are

either buried at the rnasna, or, where the family are wealthy enough Lo undertake the joul'lley, are kept for transport to Benares or Gya. On the tenth day he and the other relatives bathe, shave, anoint themselves with a mixture of oil and oil-cake, and put on clean clothes. The ohief mourner also offers to the deceased ten cakes (pinda) made of rice, milk, linseed, barley, and honey. On the eleventh day the regular ~1'(iddh, ceremony is performed with the assistance of a Kauaujia, or, failing him, of a Sakadwipi Brahman who mutters unintelligble nonsense, supposed to be Vedic texts, and the Kantaha or Mah:ibnihman is fed and receives preseuts. On the twelfth day Sakadwipi Brahmaus and friends of different castes are enterta.ined, and one pinda is offered in order that the deceased may be united to the compauy of ancestors. On the thirteenth day relatives are fed and final purification is obtained. The anniversary of the death is celebrated only once (baTkhi s/'dddh). While this is going on no marriage can take place in the family; and in order to avoid this inconvenience the b(l/,!.hi Imiddh is often performed some months before a year has elap ed from the time of death. Offerings to ancestors in general (ta1?Jan) are made through the agency of Brahmans on the 15th of the dark half of A:sin (end of ~eptember), and by the people themselves at the Nawa Khani, Jitia, and Phagua festivals. Childless relatives, lepers, persons who die a violent death, and women who die in child-birth, get only one lJinda, and are not counted as ancestors. Lepers are usually buried.

Cerenonies

The Rautias do not perform any of the ceremonies usual among . other castes during pregnancy. At child-birth assistance is ren ere y e usraln or Dagrin, who cuts the umbilical cord. The ceremonies of ch/ir.tttM, baTili, and elcaisi are performed on the sixth, twelfth, and twenty-first days after birth. If the child is born under an unlucky star (asubh lagan), a fourth ceremony, called Jataisi, is added on the twenty¬seventh day, at which Brahmans are fed, and Gauri, Ganesa, Mahadeo, and the Kut devatas or family gods worshipped. The father of the child does not lie up after its birth, or give up his ordinary occupations, but he is supposed to contract impurity (clzhutkd) by reason of the event, and must keep away from his neighbours until after the sixth day, when, if a poor man, he is purified by bathing and by giving a feast to his relatives and to Brabmans. The richer a man is, the longer is his term of impurity. 'l'olerably well-to-do Rautias remain impure till the twelfth day, while the wealthier of the castes cannot get purified till the twenty-first. When a child is six months old, its first meal of rice is com¬memorated-the ceremony of rJlunghuti, followed by m~mdan or tonsUTe. The effect of this latter rite is to remove from the mother the last traces of the pollution of child-birth, and to quality to eat flesh aud to worship the family gods. Km'nabedh, the boring of a boy's ears by the village barber, is done between the ages of six and fourteen, and is deemed to admit a boy among the grown men of the caste. Kabirpanthi members of the Bar¬gohri sub•oaste assume the sacred thread (jrmeo) when initiated into the tenets of the sect. The thread so worn is a Clthatl"i janeo. which differs from a Brahman's in the form of the knot with which it is tied.

Supertitions

The Rautias, though less plagued by the terrors of the unseen s n' world than are the Mundas and Oraons, have npers I IOns. certain superstitions which are worth recording. Spirits. Women who die in ohild-birth, persons killed by a tiger, and all oJhns or exoroists, are liable after death to reappear as bhuts, or malevolent ghosts, and give trouble to the living. In suoh oases an exorcist (oJh6. or mati) is oalled in to identify the spirit at work, and to ~p"pe~se it ~y gif.ts of money, goats, fowls, or pigs. Usually the spmt IS got nd of ill a few months, but some are speoially persistent and require annual worship to induce them to remain quiet. Spirits of this type, who were great exorcists or otherwise men of note during their life-time, often extend their influence over several families, and eventually attain the rank of a tri hal god. Babu Rakhal Das Haldar, Manager of the Chutia Nagpur estate, gives the following instance of exorcism from his personal experience. In December 1884, when the Manager was in camp at the foot of the Baragain hills in Lohardaga, a Kurmi woman of Kukui was killed by a tiger, and the tiger-demon in her form was supposed to be haunting the village. An oJlUt who was sent for to lay the ghost, took a young man to represent the tiger¬demon, and after oertain incantations put him into a kind of mes¬meric condition, in which he romped about on all fours, and generally demeaned himself like a tiger. A rope was then tied round his loins and he was dragged to a oross-road, where the volent fit passed off and he beoame insensible. In this condition he remained until the oJha reoited certain mantms and threw rice on him, when he regained his senses, and the demon was pronounced to have quitted the village. l~autias believe military service to have been their original • occupation, but this is little more than a present day most members of the caste in Lohardaga are settled agriculturists. The chief men of the caste hold taluks, Jagil's, bdmik grants, and similar ten:rres paying quit-rents direot to the Maharaja of Chutia N agpur; whIle the rank" and file are raiyats paying light rents and possessmg ocoupanoy rights. A few only are found in the comparatively reduced position of tenants of mJa's lands at full rents. In many of the tenures and occupancy holdings klwntktiti rights, entitling the tenant ~o hold at a low quit-rent, are claimed; while others are korkar, paymg only one-half of the standard rates of rent.

Social status

Socially the caste ranks fairly high, and Brahmans will take water and sweetmeats from their hands. Bar- Gohri Raautias will not eat cooked food, smoke, or drink with any but members of their own sub-caste; but they will take sweetmeats from Brahmans, Hajputs, and Srawaks. Chhot-gohris are equally particular about cooked food, but will take water and sweetmeats from, and will smoke with, Bhogtas, Ahirs, Jhoras, and Bhuyias. They also drink spirits and fermented liquors, and eat wild pigs and fowls, all of which are forbidden for the Bar-gohri sub-caste.

Representative assembly

The Chhot-gohri Rautias have a representative assembly . (mandli) for groups of from five to fifteen villages which decides questions of caste usage Each village sends one member to the mandli, which is presided over by an official called mahnnt, whose office is hereditary. When the mahant is a minor, his duties are carried on by an adult member of his family or by any Rautia unanimously chosen for this purpose by the mandli. The orders of the mal/dli are enforced by fines, by refusing to eat and drink with the oHender, and by depriving him of the servioes of the barber and washerman of the oaste. Certain acts entailing ceremonial impurity, suoh as aooidentally killing a oow or having incestuous intercourse (gotm-bf/dh) with a woman of the same gotm, admit of being atoned for by giviug a feast to Brahmans and the oaste brethren. But the wilful slaughter of a oow, the repetition of the oHenoe of gotra-badh, and the cardinal sin of eating with a person of low oaste, oannot be expiated, and in suoh extreme oases the offender is turned out of the caste. The Bar-gohri have no standing assembly, and panobayats are summoned to deal with caste questions as ocoasion requires.

Sorcery

The services of the ojha are also called in to asceliain what spirit (bhut) or witch (clain or bisdhi) has caused a particular illness, and to prescribe the cure. On such occasions he comes after sun-down and demands a winnowing fan, a small earthen lamp, rags for a wiok, a handful of arwa rice, and some oil. Having twisted a wick into the rude semblance of a hooded snake, the oJha lights his lamp and proceeds, by shaking the rice in the winnowing fan, to divine the name of the bkut or cl6in who is to blame. This point having been cleared up, he is presented with a fowl to be sacrified to his own birwat or ishla cleva, and he then performs the ceremony of kat bundh, by which he binds the patient or his family to the spirit or witch. This is supposed to put matters in train towards recovery, and the oJlui. departs, receiving from the patient's family a promise of presents of goats, etc., in the event of the treatment proving successful. Rautias are in great terror of witohes, and believe, like many people, that they can act upon their victims through objects belonging . to or intimately assooiated with them, suoh as bit. of out hair or nails; but no speoial care is taken to preserve or destroy suoh ruiicles.

Dreams are believed to be oaused by recently deceased relatives of the dreamer, who appear to him in sleep and oomplain of hunger and want of olothes, eto. Such importunate spirits ru'e easily appeased by sending for a Brahman and giving him the things whioh have been demanded in the dream. Among other ourious superstitions may be noticed the notion that a woman in the early stages of pregnancy should not cross running water. The evil eye is believed in, but its influence is attributed to inordinate appetite on the part of the perSOll who has overlooked anyone. Its effects may be averted by mixing red mustard seeds and salt, waving the mixtUl'e round the head and then throwing it into the fire. '1'0 ward off the evil eye from the crops, a blackened earthen pot with rude devices scrawled on it in white paint is stuck up in the fields. Oaths and ordeals are sometimes resorted to for the settlement of personal disputes and the decision of questions affecting caste. Ganges water, rice that he.s been offered to Jagannath, a mixtUl'e of rice and cow-dung or copper and tulsi leaves, are held in the hand and a solemn statement is made touching the matter in dispute. It is believed that some sort of misfortune will befall the person who unuer these circumstances speaks falsely, but the consequences of lying do not seem to be clearly defined. In form!>r days a more severe test was in vogue: a ring was thrown into a deep pan of boiling ghi, and the person whose conduct was in question was required to take it out with his fingers. Boys whose elder brothers bave died ill infancy are given opprobrious names, such as Akhaj, Bechan, Bechu (he who is for sale), Khudi, Chuni, GandaUl', Kinu, Lahar, Chamar, Dam or Doman, Mochi, Ghasi, Mahili (names of low castes). Girls are called by the femi!}ine forms of these names-Akhji, Chamin, etc. Rautias do not follow the custom, common among the higher castes, of giving two names-•one for ceremonial pUl'poses and the other for common use.

Lucky days for ploughing are the 12th of the light half of Katik and the 5th of the light half of Aghan for low rice lands (don), and the 1st of the dark half of Chait for high lands. The 3rd of the light half of Baisakh is good for sowing; but if there is early rain, a Brahman may be got to fix: a lucky day before this date. For tran planting the rice seedlings a lucky day may be ananged by a. Brahman at any time between the 2nd of the dark half of .tYsar and the 11th of the light half of Bhlido. It is specially unlucky to plough during the Mrigdah or Nirbisra period, called Ambubachi in Bengal, when the sun is for three days in the Mrigasira. constellation; dUl'ing the Karam festival (10th-12th of light half of Bhado) ; and on the day of the SarhUl. Rain during the Mrigdah brings bad luck; but rainy weather, while the sun is in the Rohini 01' Swati constellation, betokens good fortune. When rice is transplanted, the village paluin performs the bangal'i puja to the god of the village. When a well is sunk a Brahman is consulted as to the site and the proper time for commencing work, and a pratishtlui or dedicatory sacrifice is performed before the wat.er is used.

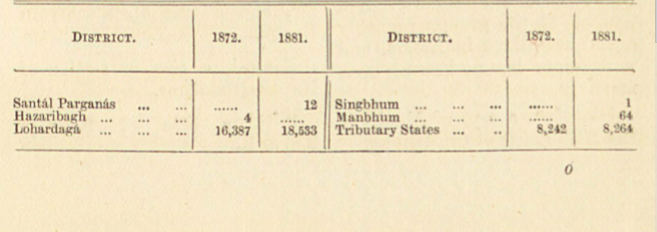

The following Btatement shows the number and distribution of Rautias in 1872 and 1881 :-